Part Four

第四部分

AROUND THE WORLD IN FIVE CHAPTERS

在五个章节中环游世界

CHAPTER 15 YALI'S PEOPLE

第十五章 耶利的族人

WHEN MY WIFE, MARIE, AND I WERE VACATIONING IN Australia one summer, we decided to visit a site with well-preserved Aboriginal rock paintings in the desert near the town of Menindee. While I knew of the Australian desert's reputation for dryness and summer heat, I had already spent long periods working under hot, dry conditions in the Californian desert and New Guinea savanna, so I considered myself experienced enough to deal with the minor challenges we would face as tourists in Australia. Carrying plenty of drinking water, Marie and I set off at noon on a hike of a few miles to the paintings.

有一年夏天,当我和妻子玛丽一起在澳大利亚度假时,我们决定去访问梅宁迪镇附近沙漠中一处保存完好的土著岩画所在地。虽然我听说过澳大利亚沙漠因干燥和夏季炎热而名闻遐迩,但在这之前我曾在加利福尼亚沙漠和新几内亚热带草原炎热干旱的条件下工作过很长时期,因此我认为自己有足够的经验去应付我们在澳大利亚旅游时可能碰到的小小的挑战。玛丽和我带上了大量饮用水,在中午出发,徒步走上了通往岩画的几英里长的道路。

The trail from the ranger station led uphill, under a cloudless sky, through open terrain offering no shade whatsoever. The hot, dry air that we were breathing reminded me of how it had felt to breathe while sitting in a Finnish sauna. By the time we reached the cliff site with the paintings, we had finished our water. We had also lost our interest in art, so we pushed on uphill, breathing slowly and regularly. Presently I noticed a bird that was unmistakably a species of babbler, but it seemed enormous compared with any known babbler species. At that point, I realized that I was experiencing heat hallucinations for the first time in my life. Marie and I decided that we had better head straight back.

我们走的小道从山间巡逻队的驻地开始,一路向上,在万里无云的晴空下,通过毫无遮蔽的开阔地带。我们呼吸着灼热干燥的空气,这使我们想起了坐在芬兰桑拿浴室里呼吸的滋味。在我们到达有岩画的峭壁时,我们已经把水喝光了。我们对艺术的兴趣也没有了,于是我们继续努力地爬山,缓慢而有规则地喘着气。不久,我看见了一只鸟,那显然是一种鹛,但比任何已知的鹛都大得多。这时,我才意识到我生平第一次被热昏了头,产生了幻觉。玛丽和我决定最好还是立刻返回。

Both of us stopped talking. As we walked, we concentrated on listening to our breathing, calculating the distance to the next landmark, and estimating the remaining time. My mouth and tongue were now dry, and Marie's face was red. When we at last reached the air-conditioned ranger station, we sagged into chairs next to the water cooler, drank down the cooler's last half-gallon of water, and asked the ranger for another bottle. Sitting there exhausted, both physically and emotionally, I reflected that the Aborigines who had made those paintings had somehow spent their entire lives in that desert without air-conditioned retreats, managing to find food as well as water.

我们俩不再说话。我们一边走路,一边倾听着自己的呼吸,计算着到下一个里程碑的距离,并估计一下还剩下多少时间。我们这时口干舌燥,玛丽满脸通红。当我们终于回到有空调的巡逻队驻地时,我们立刻瘫倒在冷却水桶旁边的椅子里,把冷却水桶里最后的半加仑水全部喝光,还向巡逻队又要来一瓶水。我们坐在那里,精疲力竭,情绪低沉,我反复思考着画那些岩画的土著人用什么办法在没有空调住所的情况下在沙漠里度过他们的一生,竟能设法不但找到了水,而且还找到了食物。

To white Australians, Menindee is famous as the base camp for two whites who had suffered worse from the desert's dry heat over a century earlier: the Irish policeman Robert Burke and the English astronomer William Wills, ill-fated leaders of the first European expedition to cross Australia from south to north. Setting out with six camels packing food enough for three months, Burke and Wills ran out of provisions while in the desert north of Menindee. Three successive times, they encountered and were rescued by well-fed Aborigines whose home was that desert, and who plied the explorers with fish, fern cakes, and roasted fat rats. But then Burke foolishly shot his pistol at one of the Aborigines, whereupon the whole group fled. Despite their big advantage over the Aborigines in possessing guns with which to hunt, Burke and Wills starved, collapsed, and died within a month after the Aborigines' departure.

对澳大利亚的白人来说,梅宁迪之所以出名,是因为一个多世纪前它是两个饱受沙漠干热之苦的白人用作补给基地的大本营。这两个白人就是爱尔兰警察罗伯特·伯克和英国天文学家威廉·威尔斯,他们是第一支从南到北纵贯澳大利亚的探险队的时运不济的领导人。伯克和威尔斯在出发时用6头骆驼驮运足够吃3个月的粮食,但在梅宁迪北方的沙漠里断了粮。一连3次,这两个探险者都碰到了吃得很好的土著并得到他们的救助。他们的家就在那片沙漠里,他们在这两个探险者的前面堆满了鱼、蕨饼和烤肥鼠。但接着伯克竟愚蠢地用手枪向其中的一个土人射击,于是整个一群土著人吓得四下逃走。虽然伯克和威尔斯因携有打猎用的枪支而拥有对土著人的巨大优势,但他们在土著人离开后不到一个月就饿得倒毙了。

My wife's and my experience at Menindee, and the fate of Burke and Wills, made vivid for me the difficulties of building a human society in Australia. Australia stands out from all the other continents: the differences between Eurasia, Africa, North America, and South America fade into insignificance compared with the differences between Australia and any of those other landmasses. Australia is by far the driest, smallest, flattest, most infertile, climatically most unpredictable, and biologically most impoverished continent. It was the last continent to be occupied by Europeans. Until then, it had supported the most distinctive human societies, and the least numerous human population, of any continent.

我和妻子在梅宁迪的经历加上伯克和威尔斯遭受的命运,使我强烈地感到在澳大利亚建立人类社会有多么困难。澳大利亚在所有大陆中显得与众不同:欧亚大陆、非洲、北美洲和南美洲之间的差异,同澳大利亚与其他这些陆块中任何一个之间的差异比较起来,显得微不足道。澳大利亚是最干燥、最小、最平坦、最贫瘠、气候最变化无常、生物品种最稀少的大陆。它是欧洲人占领的最后一个大陆。在欧洲人占领前,它已在维持着与任何大陆相比都是最具特色的人类社会和最少的人口。

Australia thus provides a crucial test of theories about intercontinental differences in societies. It had the most distinctive environment, and also the most distinctive societies. Did the former cause the latter? If so, how? Australia is the logical continent with which to begin our around-the-world tour, applying the lessons of Parts 2 and 3 to understanding the differing histories of all the continents.

因此,澳大利亚对那些关于各大陆之间社会差异的理论提供了一种决定性的检验。它有最具特色的环境,也有最具特色的社会。是前者造就了后者?如果是,又是如何做到的?澳大利亚是用来开始我们环游世界之行的合乎逻辑的大陆,我们要把本书第二部分和第三部分中所述及的经验用来了解各大陆的不同历史。

MOST LAYPEOPLE WOULD describe as the most salient feature of Native Australian societies their seeming “backwardness.” Australia is the sole continent where, in modern times, all native peoples still lived without any of the hallmarks of so-called civilization—without farming, herding, metal, bows and arrows, substantial buildings, settled villages, writing, chiefdoms, or states. Instead, Australian Aborigines were nomadic or seminomadic hunter-gatherers, organized into bands, living in temporary shelters or huts, and still dependent on stone tools. During the last 13,000 years less cultural change has accumulated in Australia than in any other continent. The prevalent European view of Native Australians was already typified by the words of an early French explorer, who wrote, “They are the most miserable people of the world, and the human beings who approach closest to brute beasts.”

大多数外行人都会把澳大利亚土著社会表面上的“落后”说成它的最重要的特点。澳大利亚是唯一的这样的大陆:那里的各个土著族群在现代的生活中仍然没有所谓文明的任何特征——没有农业,没有畜牧业,没有金属,没有弓箭,没有坚固的房屋,没有定居的村庄,没有文字,没有酋长管辖地,也没有国家。澳大利亚土著是流动的或半流动的以狩猎采集为生的人,他们组成族群,住在临时搭建的住所或简陋小屋中,并且仍然依靠石器。在过去的13000年中,澳大利亚的文化变革积累比其他任何大陆都要少。欧洲人对澳大利亚土著的流行看法,可以以早期的一个法国探险者的话为代表,他说,“他们是世界上最悲惨的人,是和没有理性的野兽差不多的人。”

Yet, as of 40,000 years ago, Native Australian societies enjoyed a big head start over societies of Europe and the other continents. Native Australians developed some of the earliest known stone tools with ground edges, the earliest hafted stone tools (that is, stone ax heads mounted on handles), and by far the earliest watercraft, in the world. Some of the oldest known painting on rock surfaces comes from Australia. Anatomically modern humans may have settled Australia before they settled western Europe. Why, despite that head start, did Europeans end up conquering Australia, rather than vice versa?

然而,直到4万年前,澳大利亚土著社会还仍然拥有对欧洲和其他大陆社会的巨大的领先优势。澳大利亚土著发明了世界上一些已知最早的、边缘经过打磨的石器,最早的有柄石器(即装有木柄的石斧)和最早的水运工具。有些已知最早的岩画也出自澳大利亚。从解剖学上看,现代人类在欧洲西部定居前可能已在澳大利亚定居了。尽管有这种领先优势,为什么最后却是欧洲人征服了澳大利亚,而不是相反?

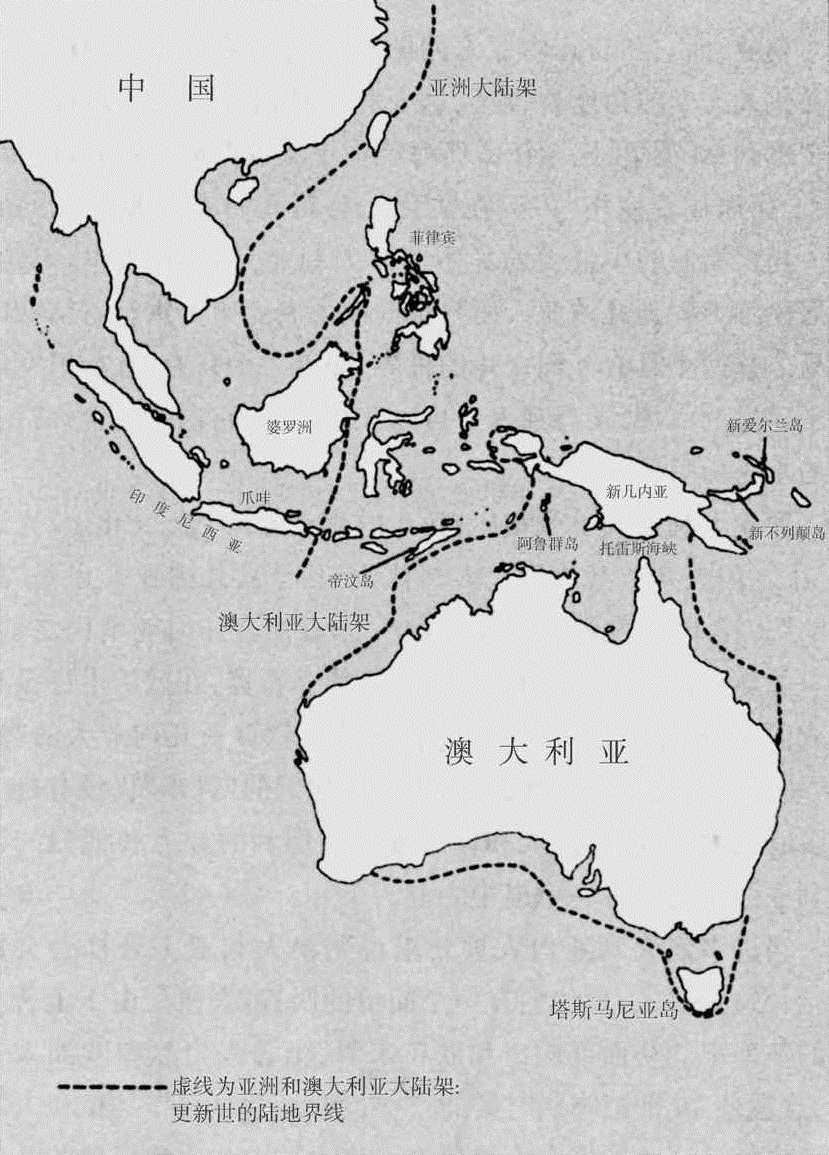

Within that question lies another. During the Pleistocene Ice Ages, when much ocean water was sequestered in continental ice sheets and sea level dropped far below its present stand, the shallow Arafura Sea now separating Australia from New Guinea was low, dry land. With the melting of ice sheets between around 12,000 and 8,000 years ago, sea level rose, that low land became flooded, and the former continent of Greater Australia became sundered into the two hemi-continents of Australia and New Guinea (Figure 15.1 on Chapter 15).

在这个问题里还有另一个问题。在更新世冰期期间,大量的海水被封闭在大陆冰原里,海平面比现在低得多,如今把澳大利亚同新几内亚分隔开来的阿拉弗拉浅海那时还是干燥的低地。随着大约12000年前到8000年前冰原的融化,海平面上升了,那块低地被海水淹没,原来的大澳大利亚大陆分成了澳大利亚和新几内亚两个半大陆(图15.1)。

Figure 15.1. Map of the region from Southeast Asia to Australia and new Guinea. Solid lines denote the present coastline; the dashed lines are e coastline during Pleistocene times when sea level dropped to below Present stand-that is, the edge of the Asian and Greater Australian expanded at that time' New Guinea and Australia we Joined in an Ponded Greater Australia, while Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and Taiwan ere part of the Asian mainland.

图15.1从东南亚到澳大利亚和新几内亚的地区图。实线表示现今海岸线;虚线为更新世时期的海岸线,那时的海平面比现在的低——就是说,当时的海岸线就是亚洲大陆架和澳大利亚大陆架的边缘。当时,新几内亚和澳大利亚连在一起,成为一个扩大了的大澳大利亚,而婆罗洲、爪哇、苏门答腊和台湾还是亚洲大陆的一部分。

The human societies of those two formerly joined landmasses were in modern times very different from each other. In contrast to everything that I just said about Native Australians, most New Guineans, such as Yali's people, were farmers and swineherds. They lived in settled villages and were organized politically into tribes rather than bands. All New Guineans had bows and arrows, and many used pottery. New Guineans tended to have much more substantial dwellings, more seaworthy boats, and more numerous and more varied utensils than did Australians. As a consequence of being food producers instead of hunter-gatherers, New Guineans lived at much higher average population densities than Australians: New Guinea has only one-tenth of Australia's area but supported a native population several times that of Australia's.

这两个原来连接在一起的陆块上的人类社会,到了现代彼此之间产生了很大的差异。与我刚才关于澳大利亚土著所说的各种情况相反,大多数新几内亚人,如耶利的族人,都是农民和猪倌。他们生活在定居的村庄里,他们的行政组织是部落,而不是族群。所有的新几内亚人都有弓箭,许多人还使用陶器。同澳大利亚人相比,新几内亚人通常都有坚固得多的住所、更多的适于航海的船只、更多数量和种类的器皿。由于新几内亚人是粮食生产者,不是以狩猎采集为生的人,所以他们的平均人口密度比澳大利亚人高得多:新几内亚的面积只有澳大利亚的十分之一,但它所养活的当地人口却数倍于澳大利亚。

Why did the human societies of the larger landmass derived from Pleistocene Greater Australia remain so “backward” in their development, while the societies of the smaller landmass “advanced” much more rapidly? Why didn't all those New Guinea innovations spread to Australia, which is separated from New Guinea by only 90 miles of sea at Torres Strait? From the perspective of cultural anthropology, the geographic distance between Australia and New Guinea is even less than 90 miles, because Torres Strait is sprinkled with islands inhabited by farmers using bows and arrows and culturally resembling New Guineans. The largest Torres Strait island lies only 10 miles from Australia. Islanders carried on a lively trade with Native Australians as well as with New Guineans. How could two such different cultural universes maintain themselves across a calm strait only 10 miles wide and routinely traversed by canoes?

为什么从更新世大澳大利亚分离出来的较大陆块上的人类社会在其发展中始终如此“落后”,而较小陆块上的社会的“进步”却快得多?为什么新几内亚的所有那些发明没有能传播到澳大利亚,而它和新几内亚之间的托雷斯海峡宽不过90英里?从文化人类学的角度看,澳大利亚和新几内亚之间的地理距离甚至不到90英里,因为托雷斯海峡中星星点点地分布着许多岛屿,上面居住着使用弓箭、在文化上与新几内亚人相类似的农民。托雷斯海峡中最大的岛距离澳大利亚只有10英里。岛上的居民不但同新几内亚人而且也同澳大利亚土著进行着活跃的贸易。这两个具有不同文化的世界,隔着一个只有10英里宽的风平浪静的海峡,又有独木舟可以互相往来,它们怎么会保持各自的本来面目的呢?

Compared with Native Australians, New Guineans rate as culturally “advanced.” But most other modern people consider even New Guineans “backward.” Until Europeans began to colonize New Guinea in the late 19th century, all New Guineans were nonliterate, dependent on stone tools, and politically not yet organized into states or (with few exceptions) chiefdoms. Granted that New Guineans had “progressed” beyond Native Australians, why had they not yet “progressed” as far as many Eurasians, Africans, and Native Americans? Thus, Yali's people and their Australian cousins pose a puzzle inside a puzzle.

同澳大利亚的土著相比,新几内亚人可以说是文化上“先进的”了。但大多数其他现代人却认为,甚至新几内亚人也是“落后的”。在19世纪晚些时候欧洲人开始在新几内亚殖民之前,所有的新几内亚人都没有文字,仍然依靠石器,在政治上还没有形成国家或(除少数例外)酋长管辖地。就算新几内亚人的“进步”超过了澳大利亚土著,那么为什么他们的“进步”仍没有赶上许多欧亚大陆人、非洲人和印第安人?耶利的族人和他们的澳大利亚同胞提出了一个谜中之谜。

When asked to account for the cultural “backwardness” of Aboriginal Australian society, many white Australians have a simple answer: supposed deficiencies of the Aborigines themselves. In facial structure and skin color, Aborigines certainly look different from Europeans, leading some late-19th century authors to consider them a missing link between apes and humans. How else can one account for the fact that white English colonists created a literate, food-producing, industrial democracy, within a few decades of colonizing a continent whose inhabitants after more than 40,000 years were still nonliterate hunter-gatherers? It is especially striking that Australia has some of the world's richest iron and aluminum deposits, as well as rich reserves of copper, tin, lead, and zinc. Why, then, were Native Australians still ignorant of metal tools and living in the Stone Age?

当许多澳大利亚白人被要求说明澳大利亚土著社会文化“落后”这个问题时,他们有一个简单的回答:大概是由于土著本身的缺陷吧。从面部构造和肤色来看,土著人当然和欧洲人不同,这就使19世纪晚些时候的一些作家把他们看作是猿和人之间缺失的一环。英国白人移民在一个大陆上建立殖民地的几十年内,创造了一种有文字的、进行粮食生产的工业民主,而这个大陆的居民在经过4万多年后仍然过着狩猎采集生活。对这个事实难道还能有其他解释?尤为引人注目的是,澳大利亚不但有蕴藏量丰富的铜、锡、铅和锌,而且还拥有某些世界上最丰富的铁矿和铝矿。那么,为什么澳大利亚土著仍然不知金属工具为何物,而仍然生活在石器时代?

It seems like a perfectly controlled experiment in the evolution of human societies. The continent was the same; only the people were different. Ergo, the explanation for the differences between Native Australian and European-Australian societies must lie in the different people composing them. The logic behind this racist conclusion appears compelling. We shall see, however, that it contains a simple error.

这好像对人类社会的一次完全有控制的试验。大陆还是那个大陆,只是人不同罢了。因此,对澳大利亚土著社会和欧洲裔澳大利亚人社会之间的差异的解释,想必就是由于组成这两种社会的不同的人。这种种族主义结论背后的逻辑似乎使人不得不信。然而,我们将会看到,这种结论包含着一个简单的错误。

AS THE FIRST step in examining this logic, let us examine the origins of the peoples themselves. Australia and New Guinea were both occupied by at least 40,000 years ago, at a time when they were both still joined as Greater Australia. A glance at a map (Figure 15.1) suggests that the colonists must have originated ultimately from the nearest continent, Southeast Asia, by island hopping through the Indonesian Archipelago. This conclusion is supported by genetic relationships between modern Australians, New Guineans, and Asians, and by the survival today of a few populations of somewhat similar physical appearance in the Philippines, Malay Peninsula, and Andaman Islands off Myanmar.

作为检验这个逻辑的第一步,让我们考查一下这些人本身的起源。澳大利亚和新几内亚至少在4万年前就已有人居住了,那时它们还是连在一起的大澳大利亚。只要看一眼地图(图15.1)就可知道,移民们最后必定来自最近的大陆东南亚,他们逐岛前进,通过印度尼西亚群岛来到了大澳大利亚。作为这一结论佐证的,有现代澳大利亚人、新几内亚人和亚洲人之间在遗传学上的关系,还有在今天的菲律宾、马来半岛和缅甸外海的安达曼群岛还残存的几个具有类似体貌特征的群体。

Once the colonists had reached the shores of Greater Australia, they spread quickly over the whole continent to occupy even its farthest reaches and most inhospitable habitats. By 40,000 years ago, fossils and stone tools attest to their presence in Australia's southwestern corner; by 35,000 years ago, in Australia's southeastern corner and Tasmania, the corner of Australia most remote from the colonists' likely beachhead in western Australia or New Guinea (the parts nearest Indonesia and Asia); and by 30,000 years ago, in the cold New Guinea highlands. All of those areas could have been reached overland from a western beachhead. However, the colonization of both the Bismarck and the Solomon Archipelagoes northeast of New Guinea, by 35,000 years ago, required further overwater crossings of dozens of miles. The occupation could have been even more rapid than that apparent spread of dates from 40,000 to 30,000 years ago, since the various dates hardly differ within the experimental error of the radiocarbon method.

这些移民一旦到达大澳大利亚海岸,就在整个大陆迅速扩散,甚至占据了这个大陆的最遥远的地方和最不适于居住的处所。一些4万年前的化石和石器证实了他们曾在澳大利亚西南角存在过;到35000年前,他们到了澳大利亚东西角和塔斯马尼亚,这是澳大利亚离开这些移民在澳大利亚西部或新几内亚可能的登陆地点最遥远的角落(离印度尼西亚和亚洲最近的地方);而到了3万年前,他们则到了新几内亚气候寒冷的高原地区。所有这些地区都可以从西面的某个登陆地点经由陆路到达。然而,到35000年前,要向新几内亚东北方的俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛移民,还需要渡过几十英里的水路。对大澳大利亚的占领在速度上可能比从4万年前到3万年前的一些年代里表面上的扩散甚至更为迅速,因为在用碳-14测定法的实验误差范围内,这些不同的年代几乎没有什么区别。

At the Pleistocene times when Australia and New Guinea were initially occupied, the Asian continent extended eastward to incorporate the modern islands of Borneo, Java, and Bali, nearly 1,000 miles nearer to Australia and New Guinea than Southeast Asia's present margin. However, at least eight channels up to 50 miles wide still remained to be crossed in getting from Borneo or Bali to Pleistocene Greater Australia. Forty thousand years ago, those crossings may have been achieved by bamboo rafts, low-tech but seaworthy watercraft still in use in coastal South China today. The crossings must nevertheless have been difficult, because after that initial landfall by 40,000 years ago the archaeological record provides no compelling evidence of further human arrivals in Greater Australia from Asia for tens of thousands of years. Not until within the last few thousand years do we encounter the next firm evidence, in the form of the appearance of Asian-derived pigs in New Guinea and Asian-derived dogs in Australia.

在澳大利亚和新几内亚最早有人居住的更新世,亚洲大陆向东延伸,吸纳了现代的婆罗洲[1]、爪哇和巴厘这些岛屿,所以当时亚洲大陆与澳大利亚和新几内亚的距离,比今天东南亚边缘到澳大利亚和新几内亚的距离要近差不多1000英里。然而,从婆罗洲或巴厘岛到达更新世的大澳大利亚,仍然要渡过至少8个宽达50英里的海峡。4万年前,渡过这些海峡可能要靠竹筏,这是一种低技术的水运工具,但适于航海,今天的华南沿海仍在使用。尽管如此,当年渡过这些海峡想必十分困难,因为在4万年前最早的那次登陆后,考古记录没有提供任何令人信服的证据来证明在后来的几万年中又有人类从亚洲到达大澳大利亚。我们随后得到的明确证据是,直到最近的几千年内,才在新几内亚出现了来自亚洲的猪和在澳大利亚出现了来自亚洲的狗。

Thus, the human societies of Australia and New Guinea developed in substantial isolation from the Asian societies that founded them. That isolation is reflected in languages spoken today. After all those millennia of isolation, neither modern Aboriginal Australian languages nor the major group of modern New Guinea languages (the so-called Papuan languages) exhibit any clear relationships with any modern Asian languages.

因此,澳大利亚和新几内亚的人类社会,是在与建立它们的亚洲社会基本隔绝的情况下发展起来的。这种隔绝状态在今天所说的语言中反映了出来。经过这几千年的隔绝,现代澳大利亚土著语言和现代新几内亚主要群体的语言(所谓巴布亚语),都没有显示出与任何现代亚洲语言有任何明显的关系。

The isolation is also reflected in genes and physical anthropology. Genetic studies suggest that Aboriginal Australians and New Guinea highlanders are somewhat more similar to modern Asians than to peoples of other continents, but the relationship is not a close one. In skeletons and physical appearance, Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans are also distinct from most Southeast Asian populations, as becomes obvious if one compares photos of Australians or New Guineans with those of Indonesians or Chinese. Part of the reason for all these differences is that the initial Asian colonists of Greater Australia have had a long time in which to diverge from their stay-at-home Asian cousins, with only limited genetic exchanges during most of that time. But probably a more important reason is that the original Southeast Asian stock from which the colonists of Greater Australia were derived has by now been largely replaced by other Asians expanding out of China.

这种隔绝状态也反映在遗传与体质人类学上。对基因的研究表明,澳大利亚土著与新几内亚高原居民同现代亚洲人的类似之处,要稍多于与其他大陆人的类似之处,不过这种关系并不密切。在骨骼和体貌方面,澳大利亚和新几内亚的土著与大多数东南亚人也有区别,如果把澳大利亚人或新几内亚人的照片同印度尼西亚人或中国人的照片比较一下,这一点就变得十分明显。所有这些差异的部分原因是,大澳大利亚最早的亚洲移民在一段漫长的时间里与他们的呆在家乡的亚洲同胞分道扬镳,在大部分时间里只发生有限的遗传交换。不过,也许一个更重要的原因是,大澳大利亚移民原来在东南亚的祖先,到这时已大部分被从中国向外扩张的其他亚洲人取代了。

Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans have also diverged genetically, physically, and linguistically from each other. For instance, among the major (genetically determined) human blood groups, groups B of the so-called ABO system and S of the MNS system occur in New Guinea as well as in most of the rest of the world, but both are virtually absent in Australia. The tightly coiled hair of most New Guineans contrasts with the straight or wavy hair of most Australians. Australian languages and New Guinea's Papuan languages are unrelated not only to Asian languages but also to each other, except for some spread of vocabulary in both directions across Torres Strait.

澳大利亚和新几内亚土著在遗传上、体质上和语言上也产生了分化。例如,在人类主要的(由遗传决定的)血型中,所谓ABO系统中的B型和MNS系统中的S型,在新几内亚同在世界上其他大多数地区一样都有出现,但这两种血型在澳大利亚则几乎没有。大多数新几内亚人的浓密卷曲的头发与大多数澳大利亚人的直发或鬈发是明显不同的。澳大利亚的语言与新几内亚的巴布亚语言不但同亚洲语言没有亲缘关系,而且彼此之间也没有亲缘关系,只不过是托雷斯海峡两岸双向交流了某些词汇而已。

All that divergence of Australians and New Guineans from each other reflects lengthy isolation in very different environments. Since the rise of the Arafura Sea finally separated Australia and New Guinea from each other around 10,000 years ago, gene exchange has been limited to tenuous contact via the chain of Torres Strait islands. That has allowed the populations of the two hemi-continents to adapt to their own environments. While the savannas and mangroves of coastal southern New Guinea are fairly similar to those of northern Australia, other habitats of the hemi-continents differ in almost all major respects.

澳大利亚人和新几内亚人之间的这种分化,反映了在十分不同的环境里的长期隔绝状况。自从阿拉弗拉海在大约1万年前由于海平面上升而最后把澳大利亚同新几内亚分开以来,遗传交换只限于通过托雷斯海峡中一系列岛屿而进行的稀少的接触。这就使得这两个半大陆上的居民适应了各自的环境。虽然新几内亚南部沿海的热带草原和红树林,与澳大利亚北部的热带草原和红树林有相当多的类似之处,但这两个半大陆的其他生境在几乎所有的主要方面都是不同的。

Here are some of the differences. New Guinea lies nearly on the equator, while Australia extends far into the temperate zones, reaching almost 40 degrees south of the equator. New Guinea is mountainous and extremely rugged, rising to 16,500 feet and with glaciers capping the highest peaks, while Australia is mostly low and flat—94 percent of its area lies below 2,000 feet of elevation. New Guinea is one of the wettest areas on Earth, Australia one of the driest. Most of New Guinea receives over 100 inches of rain annually, and much of the highlands receives over 200 inches, while most of Australia receives less than 20 inches. New Guinea's equatorial climate varies only modestly from season to season and year to year, but Australia's climate is highly seasonal and varies from year to year far more than that of any other continent. As a result, New Guinea is laced with permanent large rivers, while Australia's permanently flowing rivers are confined in most years to eastern Australia, and even Australia's largest river system (the Murray-Darling) has ceased flowing for months during droughts. Most of New Guinea's land area is clothed in dense rain forest, while most of Australia's supports only desert and open dry woodland.

这里举几个不同的地方。新几内亚紧靠赤道,而澳大利亚则远远地延伸进温带,几乎到达赤道以南40度的地方。新几内亚多山,地势极其崎岖不平,高度可达16500英尺,最高的山峰上覆盖着冰川,而澳大利亚大都地势低平——94%的地区的海拔高度在2000英尺以下。新几内亚是地球上最潮湿的地区之一,而澳大利亚则是地球上最干燥的地区之一。新几内亚大部分地区的年降雨量为100英寸,很大一部分高原地区则超过200英寸,而澳大利亚的大部分地区的年降雨量则不到20英寸。新几内亚的赤道气候只有不太大的季节变化,而且年年如此,但澳大利亚的气候则是高度季节性的,而且年年不同,其变幻莫测远远超过其他任何大陆的气候。因此,新几内亚境内的大河纵横交错,川流不息,而澳大利亚的永久性河流在大多数年份里只限于东部地区,甚至澳大利亚最大的水系(墨累河-达令河水系)在发生干旱时也要断流达数月之久。新几内亚的大部分陆地覆盖着茂密的雨林,而澳大利亚大部分地区却只有沙漠和开阔干旱的林地。

New Guinea is covered with young fertile soil, as a consequence of volcanic activity, glaciers repeatedly advancing and retreating and scouring the highlands, and mountain streams carrying huge quantities of silt to the lowlands. In contrast, Australia has by far the oldest, most infertile, most nutrient-leached soils of any continent, because of Australia's little volcanic activity and its lack of high mountains and glaciers. Despite having only one-tenth of Australia's area, New Guinea is home to approximately as many mammal and bird species as is Australia—a result of New Guinea's equatorial location, much higher rainfall, much greater range of elevations, and greater fertility. All of those environmental differences influenced the two hemi-continents' very disparate cultural histories, which we shall now consider.

新几内亚覆盖着受侵蚀尚少的肥沃土壤,这是火山活动、冰川的反复进退与冲刷高原以及山间溪流把大量泥沙带到低地所造成的结果。相形之下,澳大利亚有的则是所有大陆中最古老、最贫瘠、养分被滤去最多的土壤,因为澳大利亚很少有火山活动,也没有高山和冰川。尽管新几内亚的面积只有澳大利亚的十分之一,但由于新几内亚地处赤道附近,雨量充沛,地势高低错落和土壤肥沃,那里成了几乎同在澳大利亚一样多的哺乳动物和鸟类的生息之地。所有这些环境方面的差异,影响了这两个半大陆的全然不同的文化史,现在我们就来考察一下这个问题。

THE EARLIEST AND most intensive food production, and the densest populations, of Greater Australia arose in the highland valleys of New Guinea at altitudes between 4,000 and 9,000 feet above sea level. Archaeological excavations uncovered complex systems of drainage ditches dating back to 9,000 years ago and becoming extensive by 6,000 years ago, as well as terraces serving to retain soil moisture in drier areas. The ditch systems were similar to those still used today in the highlands to drain swampy areas for use as gardens. By around 5,000 years ago, pollen analyses testify to widespread deforestation of highland valleys, suggesting forest clearance for agriculture.

大澳大利亚最早、最集约的粮食生产和最稠密的人口,出现在新几内亚海拔高度为4000到9000英尺的高原河谷地区。考古发掘不但发现了在比较干旱地区用来保持土壤水分的梯田,还发现了复杂的排水沟系统,其年代为9000年前,而到了6000年前已变得相当普遍。这种沟渠系统类似于今天在这高原地区仍然用来疏干沼泽地使之成为园地的那些沟渠系统。花粉分析表明,到大约5000年前,高地河谷普遍发生了砍伐森林的行动,从而使人联想到清除森林是为了发展农业。

Today, the staple crops of highland agriculture are the recently introduced sweet potato, along with taro, bananas, yams, sugarcane, edible grass stems, and several leafy vegetables. Because taro, bananas, and yams are native to Southeast Asia, an undoubted site of plant domestication, it used to be assumed that New Guinea highland crops other than sweet potatoes arrived from Asia. However, it was eventually realized that the wild ancestors of sugarcane, the leafy vegetables, and the edible grass stems are New Guinea species, that the particular types of bananas grown in New Guinea have New Guinea rather than Asian wild ancestors, and that taro and some yams are native to New Guinea as well as to Asia. If New Guinea agriculture had really had Asian origins, one might have expected to find highland crops derived unequivocally from Asia, but there are none. For those reasons it is now generally acknowledged that agriculture arose indigenously in the New Guinea highlands by domestication of New Guinea wild plant species.

今天,新几内亚高原地区的主要农作物是不久前引进的甘薯,加上芋艿、香蕉、薯蓣、甘蔗、一些可吃的草茎和几种叶菜。由于芋艿、香蕉和薯蓣是在东南亚土生土长的,而东南亚又是一个无可争辩的植物驯化场所,所以过去人们通常认为,新几内亚高原地区的作物,除甘薯外,都来自亚洲。然而,人们最后还是认识到,甘蔗、叶菜和可吃的草茎的野生祖先都是新几内亚的品种,生长在新几内亚的某几种香蕉的野生祖先是在新几内亚而不是在亚洲,而芋艿和某些薯蓣不但是亚洲的土产,而且也是新几内亚的土产。如果新几内亚的农业真的来自亚洲,人们也许会指望在高原地区找到明白无误地来自亚洲的作物,但没有找到。由于这些原因,现在人们普遍承认,新几内亚高原地区的农业是通过对新几内亚野生植物的驯化而在当地出现的。

New Guinea thus joins the Fertile Crescent, China, and a few other regions as one of the world's centers of independent origins of plant domestication. No remains of the crops actually being grown in the highlands 6,000 years ago have been preserved in archaeological sites. However, that is not surprising, because modern highland staple crops are plant species that do not leave archaeologically visible residues except under exceptional conditions. Hence it seems likely that some of them were also the founding crops of highland agriculture, especially as the ancient drainage systems preserved are so similar to the modern drainage systems used for growing taro.

因此,新几内亚和新月沃地、中国以及其他几个地区一样,成为世界上植物独立驯化发源地的中心之一。在一些考古遗址没有发现6000年前在高原地区实际种植的作物有任何残余保存下来。不过,这一点并不令人惊奇,因为除非在特殊情况下,现代高原地区的主要作物都是不会留下明显的考古残迹的那类植物。因此,其中的一些植物也是高原地区农业的始祖作物,这似乎是可能的,而由于保存下来的古代排水系统与现代用于种植芋艿的排水系统如此相似,这种情况就尤其可能。

The three unequivocally foreign elements in New Guinea highland food production as seen by the first European explorers were chickens, pigs, and sweet potatoes. Chickens and pigs were domesticated in Southeast Asia and introduced around 3,600 years ago to New Guinea and most other Pacific islands by Austronesians, a people of ultimately South Chinese origin whom we shall discuss in Chapter 17. (Pigs may have arrived earlier.) As for the sweet potato, native to South America, it apparently reached New Guinea only within the last few centuries, following its introduction to the Philippines by Spaniards. Once established in New Guinea, the sweet potato overtook taro as the highland's leading crop, because of its shorter time required to reach maturity, higher yields per acre, and greater tolerance of poor soil conditions.

最早的欧洲探险者所看到的新几内亚高原地区粮食生产中3个明确的外来因素是鸡、猪和甘薯。鸡和猪是在东南亚驯化的,并于大约3600年前由南岛人引进新几内亚和其他大多数太平洋岛屿。这些人源自中国华南的一个民族,我们将在第十七章对他们予以讨论。(猪的引进可能还要早些。)至于原产南美的甘薯,显然只是在最近几个世纪内才到达新几内亚,是由西班牙人引进菲律宾,再由菲律宾引进新几内亚的。甘薯一旦在新几内亚移植生长,就取代了芋艿的地位而成为高原地区的主要作物,因为它成熟的时间更短,每英亩的产量更高,并对贫瘠的土壤条件具有更大的耐性。

The development of New Guinea highland agriculture must have triggered a big population explosion thousands of years ago, because the highlands could have supported only very low population densities of hunter-gatherers after New Guinea's original megafauna of giant marsupials had been exterminated. The arrival of the sweet potato triggered a further explosion in recent centuries. When Europeans first flew over the highlands in the 1930s, they were astonished to see below them a landscape similar to Holland's. Broad valleys were completely deforested and dotted with villages, and drained and fenced fields for intensive food production covered entire valley floors. That landscape testifies to the population densities achieved in the highlands by farmers with stone tools.

新几内亚高原地区的农业发展,想必是几千年前巨大的人口爆炸引发的,因为在新几内亚原来大群的大型有袋动物灭绝之后,高原地区只能养活人口密度很低的以狩猎采集为生的人。甘薯的引进在最近的几个世纪中引发了又一次的人口爆炸。当欧洲人于20世纪30年代第一次飞越高原地区的上空时,他们惊讶地发现下面的景色与荷兰的景色颇为相似。宽阔谷地里的森林被砍伐一空,星星点点地散布着一些村庄,整个谷底都是为进行集约型粮食生产而疏干的并用篱笆围起来的田地。这片景色证明了使用石器的农民在高原地区所达到的人口密度。

Steep terrain, persistent cloud cover, malaria, and risk of drought at lower elevations confine New Guinea highland agriculture to elevations above about 4,000 feet. In effect, the New Guinea highlands are an island of dense farming populations thrust up into the sky and surrounded below by a sea of clouds. Lowland New Guineans on the seacoast and rivers are villagers depending heavily on fish, while those on dry ground away from the coast and rivers subsist at low densities by slash-and-burn agriculture based on bananas and yams, supplemented by hunting and gathering. In contrast, lowland New Guinea swamp dwellers live as nomadic hunter-gatherers dependent on the starchy pith of wild sago palms, which are very productive and yield three times more calories per hour of work than does gardening. New Guinea swamps thus provide a clear instance of an environment where people remained hunter-gatherers because farming could not compete with the hunting-gathering lifestyle.

地势陡峭、终年云雾缭绕、疟疾流行以及低海拔地区有发生干旱之虞,使新几内亚高原地区的农业只能在海拔高度约4000英尺的地带发展。事实上,新几内亚高原地区只是一个有稠密农业人口的孤岛,上插青天,下绕云海。新几内亚沿江沿海的低地上的村民主要以渔业为生,而远离海岸和江河的旱地居民人口密度很低,靠刀耕火种农业维持生计,以种植香蕉和薯蓣为主,以狩猎和采集为辅。相比之下,新几内亚低地沼泽地居民则过着流动的狩猎采集生活,靠野生西谷椰子含淀粉的木髓为生,这种树1小时采集的结果可以产生比栽培植物多3倍的卡路里。因此,新几内亚的沼泽地提供了一个清楚的例子,说明在某种环境里,由于农业还不能与狩猎采集的生活方式竞争,所以那里的人仍然以狩猎采集为生。

The sago eaters persisting in lowland swamps exemplify the nomadic hunter-gatherer band organization that must formerly have characterized all New Guineans. For all the reasons that we discussed in Chapters 13 and 14, the farmers and the fishing peoples were the ones to develop more-complex technology, societies, and political organization. They live in permanent villages and tribal societies, often led by a big-man. Some of them construct large, elaborately decorated, ceremonial houses. Their great art, in the form of wooden statues and masks, is prized in museums around the world.

在低地沼泽靠吃西谷椰子而维生的人,就是四处流动的狩猎采集族群组织的典型例子,这种族群组织以前想必是新几内亚的特征。由于我们在第十三章和第十四章中讨论过的所有那些原因,农民和渔民就成了发明更复杂的技术、社会和政治组织的人。他们生活在定居的村庄和部落社会中,常常由一个大人物来领导。有些部落还建有巨大的、精心装饰起来的、供举行仪式的屋宇。他们的伟大艺术木雕人像和面具,为全世界的博物馆所珍藏。

NEW GUINEA THUS became the part of Greater Australia with the most-advanced technology, social and political organization, and art. However, from an urban American or European perspective, New Guinea still rates as “primitive” rather than “advanced.” Why did New Guineans continue to use stone tools instead of developing metal tools, remain nonliterate, and fail to organize themselves into chiefdoms and states? It turns out that New Guinea had several biological and geographic strikes against it.

这样,新几内亚就成为大澳大利亚的一部分,拥有最先进的技术、社会和政治组织以及艺术。然而,从习惯于城市生活的美国人或欧洲人的观点看,新几内亚仍然是“原始的”,而不是“先进的”。为什么新几内亚人仍然在使用石器而不是发展金属工具,仍然没有文字,并且不能把自己组成酋长管辖地和国家?原来新几内亚有几个不利于它的生物因素和地理因素。

First, although indigenous food production did arise in the New Guinea highlands, we saw in Chapter 8 that it yielded little protein. The dietary staples were low-protein root crops, and production of the sole domesticated animal species (pigs and chickens) was too low to contribute much to people's protein budgets. Since neither pigs nor chickens can be harnessed to pull carts, highlanders remained without sources of power other than human muscle power, and also failed to evolve epidemic diseases to repel the eventual European invaders.

首先,虽然本地的粮食生产的确是在新几内亚高原地区出现的,但我们已在第八章中看到,它产出的蛋白质很少。当地的主食都是低蛋白的根用作物,而唯一的驯化动物(猪和鸡)的产量又太低,不能为人们提供大量的蛋白质。既然无法把猪或鸡套起来拉车,高原地区的居民除了两臂力气外,仍然没有其他动力来源,而且也未能发展出流行疾病以击退终于侵入的欧洲人。

A second restriction on the size of highland populations was the limited available area: the New Guinea highlands have only a few broad valleys, notably the Wahgi and Baliem Valleys, capable of supporting dense populations. Still a third limitation was the reality that the mid-montane zone between 4,000 and 9,000 feet was the sole altitudinal zone in New Guinea suitable for intensive food production. There was no food production at all in New Guinea alpine habitats above 9,000 feet, little on the hillslopes between 4,000 and 1,000 feet, and only low-density slash-and-burn agriculture in the lowlands. Thus, large-scale economic exchanges of food, between communities at different altitudes specializing in different types of food production, never developed in New Guinea. Such exchanges in the Andes, Alps, and Himalayas not only increased population densities in those areas, by providing people at all altitudes with a more balanced diet, but also promoted regional economic and political integration.

对高原地区人口数量的第二个限制,是能够利用的土地面积有限:新几内亚高原地区只有几处宽阔的谷地(最显著的是瓦吉谷地和巴利姆谷地)能够养活稠密的人口。第三个限制是这样的现实,即4000英尺至9000英尺之间的中间山地森林地带,是新几内亚唯一适于集约型粮食生产的高程地带。在9000英尺以上的新几内亚高山生境根本没有任何粮食生产,在4000英尺至1000英尺之间的山坡上几乎没有什么粮食生产,而在低地地区也只有低密度的刀耕火种农业。因此,在不同海拔高度专门从事不同类型粮食生产的一些社会之间对粮食的大规模经济交换,在新几内亚从未发展起来。在安第斯山脉、阿尔卑斯山脉和喜马拉雅山脉,这种交换不但向各个海拔高度的人提供一种比较均衡的饮食,从而增加了这些地区的人口密度,而且也促进了地区的经济和政治一体化。

For all these reasons, the population of traditional New Guinea never exceeded 1,000,000 until European colonial governments brought Western medicine and the end of intertribal warfare. Of the approximately nine world centers of agricultural origins that we discussed in Chapter 5, New Guinea remained the one with by far the smallest population. With a mere 1,000,000 people, New Guinea could not develop the technology, writing, and political systems that arose among populations of tens of millions in China, the Fertile Crescent, the Andes, and Mesoamerica.

由于这种种原因,在欧洲殖民政府带来西方医药并制止部落战争之前,传统的新几内亚的人口从未超过100万人。我们在第五章讨论过全世界大约有9个最早的农业中心,其中新几内亚始终是人口最少的一个中心。由于只有100万人口,新几内亚不可能发明出像在中国、新月沃地、安第斯山脉地区和中美洲的几千万人中出现的那种技术、文字和政治制度。

New Guinea's population is not only small in aggregate, but also fragmented into thousands of micropopulations by the rugged terrain: swamps in much of the lowlands, steep-sided ridges and narrow canyons alternating with each other in the highlands, and dense jungle swathing both the lowlands and the highlands. When I am engaged in biological exploration in New Guinea, with teams of New Guineans as field assistants, I consider excellent progress to be three miles per day even if we are traveling over existing trails. Most highlanders in traditional New Guinea never went more than 10 miles from home in the course of their lives.

新几内亚的人口不但总数少,而且还由于崎岖的地形而被分割成数以千计的生存于特定区域内的群体——这里有低地地区的大量沼泽地、高原地区交替出现的陡峭的山岭和狭窄的峡谷以及低地和高原四周茂密的丛林。当我带领一队从事野外作业的新几内亚助手们在新几内亚进行生物调查时,虽然我们走的是现存的小路,但我认为每天前进3英里仍是非常快的速度。传统的新几内亚高原地区的居民一生中离家外出从来不超过10英里。

Those difficulties of terrain, combined with the state of intermittent warfare that characterized relations between New Guinea bands or villages, account for traditional New Guinea's linguistic, cultural, and political fragmentation. New Guinea has by far the highest concentration of languages in the world: 1,000 out of the world's 6,000 languages, crammed into an area only slightly larger than that of Texas, and divided into dozens of language families and isolated languages as different from each other as English is from Chinese. Nearly half of all New Guinea languages have fewer than 500 speakers, and even the largest language groups (still with a mere 100,000 speakers) were politically fragmented into hundreds of villages, fighting as fiercely with each other as with speakers of other languages. Each of those microsocieties alone was far too small to support chiefs and craft specialists, or to develop metallurgy and writing.

地形造成的这些困难,加上构成新几内亚族群或村落之间关系特点的断断续续的战争状态,正好说明了传统的新几内亚在语言、文化和政治方面的这种支离破碎的状况。新几内亚是世界上语言最集中的地方:全世界6000种语言中有1000种挤在一个只比得克萨斯州稍大一点的地区里,分成几十个语族以及一些就像英语和汉语那样不同的互相独立的语言。在所有新几内亚语言中,差不多有一半语言说的人不到500,甚至那些最大的说同一种语言的群体(说的人仍然只有10万)也在政治上分成几百个村庄,彼此凶狠地斗殴,就像同说其他语言的人斗殴一样。每一个这样的小社会其自身实在太小,无法养活酋长和专门的手艺人,也无法发明出冶金术和文字。

Besides a small and fragmented population, the other limitation on development in New Guinea was geographic isolation, restricting the inflow of technology and ideas from elsewhere. New Guinea's three neighbors were all separated from New Guinea by water gaps, and until a few thousand years ago they were all even less advanced than New Guinea (especially the New Guinea highlands) in technology and food production. Of those three neighbors, Aboriginal Australians remained hunter-gatherers with almost nothing to offer New Guineans that New Guineans did not already possess. New Guinea's second neighbor was the much smaller islands of the Bismarck and the Solomon Archipelagoes to the east. That left, as New Guinea's third neighbor, the islands of eastern Indonesia. But that area, too, remained a cultural backwater occupied by hunter-gatherers for most of its history. There is no item that can be identified as having reached New Guinea via Indonesia, after the initial colonization of New Guinea over 40,000 years ago, until the time of the Austronesian expansion around 1600 B.C.

除少而分散的人口外,新几内亚的发展所受到的另一限制是地理上的与世隔绝的状态,这一状态妨碍了技术和思想从别处流入新几内亚。新几内亚的3个邻居全都被溪涧流过的峡谷把它们同新几内亚分隔开来,直到几千年前,这些邻居在技术和粮食生产方面甚至比新几内亚(尤其是新几内亚的高原地区)还要落后。在这3个邻居中,澳大利亚土著仍然以狩猎采集为生,新几内亚人所没有的东西,他们几乎全都无法提供。新几内亚的第二个邻居是东面的小得多的俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛。新几内亚的第三个邻居就是印度尼西亚东部的那些岛屿。但这个地区在其历史的大部分时间里也始终是由狩猎采集族群占据的文化落后地区。从4万多年前新几内亚最早有人移居时起,直到公元前1600年左右南岛人扩张时止,没有一样东西可以确定是经由印度尼西亚传到新几内亚的。

With that expansion, Indonesia became occupied by food producers of Asian origins, with domestic animals, with agriculture and technology at least as complex as New Guinea's, and with navigational skills that served as a much more efficient conduit from Asia to New Guinea. Austronesians settled on islands west and north and east of New Guinea, and in the far west and on the north and southeast coasts of New Guinea itself. Austronesians introduced pottery, chickens, and probably dogs and pigs to New Guinea. (Early archaeological surveys claimed pig bones in the New Guinea highlands by 4000 B.C., but those claims have not been confirmed.) For at least the last thousand years, trade connected New Guinea to the technologically much more advanced societies of Java and China. In return for exporting bird of paradise plumes and spices, New Guineans received Southeast Asian goods, including even such luxury items as Dong Son bronze drums and Chinese porcelain.

随着这一扩张,印度尼西亚就为来自亚洲的粮食生产者所占有,他们带来了家畜,带来了至少同新几内亚的一样复杂的农业和技术,还带来了可以被用作从亚洲前往新几内亚的有效得多的手段的航海技术。南岛人在新几内亚西面、北面和东面的一些岛屿上定居下来,并进一步向西深入,在新几内亚本土北部和东南部海岸定居。南岛人把陶器、鸡,可能还有狗和猪引进新几内亚。(早期的考古调查曾宣布在新几内亚高原地区发现了不迟于公元前4000年前的猪骨,不过这些宣布一直未得到证实。)至少在过去的几千年中,贸易往来把新几内亚同技术上先进得多的爪哇社会和中国社会连接了起来。作为对出口天堂鸟羽毛和香料的交换,新几内亚人得到了东南亚的货物,其中甚至包括诸如东山[2]铜鼓和中国瓷器之类的奢侈品。

With time, the Austronesian expansion would surely have had more impact on New Guinea. Western New Guinea would eventually have been incorporated politically into the sultanates of eastern Indonesia, and metal tools might have spread through eastern Indonesia to New Guinea. But—that hadn't happened by A.D. 1511, the year the Portuguese arrived in the Moluccas and truncated Indonesia's separate train of developments. When Europeans reached New Guinea soon thereafter, its inhabitants were still living in bands or in fiercely independent little villages, and still using stone tools.

假以时日,南岛人的这一扩张肯定会对新几内亚产生更大的影响。新几内亚西部地区可能最后在政治上并入印度尼西亚东部苏丹的领土,而金属工具也可能通过印度尼西亚东部传入新几内亚。但是——这种情况直到公元1511年都没有发生,而就在这一年,葡萄牙人到达摩鹿加群岛[3],缩短了印度尼西亚各个发展阶段的序列。其后不久,当欧洲人到达新几内亚时,当地居民仍然生活在族群或极其独立的小村庄中,并且仍然在使用石器。

WHILE THE NEW Guinea hemi-continent of Greater Australia thus developed both animal husbandry and agriculture, the Australian hemi-continent developed neither. During the Ice Ages Australia had supported even more big marsupials than New Guinea, including diprotodonts (the marsupial equivalent of cows and rhinoceroses), giant kangaroos, and giant wombats. But all those marsupial candidates for animal husbandry disappeared in the wave of extinctions (or exterminations) that accompanied human colonization of Australia. That left Australia, like New Guinea, with no domesticable native mammals. The sole foreign domesticated mammal adopted in Australia was the dog, which arrived from Asia (presumably in Austronesian canoes) around 1500 B.C. and established itself in the wild in Australia to become the dingo. Native Australians kept captive dingos as companions, watchdogs, and even as living blankets, giving rise to the expression “five-dog night” to mean a very cold night. But they did not use dingos / dogs for food, as did Polynesians, or for cooperative hunting of wild animals, as did New Guineans.

虽然大澳大利亚的新几内亚这个半大陆就这样发展了家畜饲养业和农业,但澳大利亚这个半大陆对这两项都没有发展起来。在冰川期,澳大利亚的有袋目动物甚至比新几内亚还多,其中包括袋牛(相当于牛和犀牛的有袋目动物)、大袋鼠和大毛鼻袋熊。但所有这些本来可以用来饲养的有袋目动物,在随着人类移居澳大利亚而到来的动物灭绝的浪潮中消失了。这就使澳大利亚同新几内亚一样没有了任何可以驯化的本地哺乳动物。唯一在澳大利亚被采纳的外来驯化哺乳动物是狗,而狗是在公元前1500年左右从亚洲引进的(大概是乘坐南岛人的独木舟来到的),并在澳大利亚的荒野里定居而变成澳洲野犬。澳大利亚当地人把这种野犬捉来饲养,把它们当作伴侣、看门狗,甚至当作活毯子,于是就有了“五条狗的夜晚”这种说法,形容夜晚很冷。但他们并不像波利尼西亚人那样把野犬/狗当食物,也不像新几内亚人那样把它们用作打猎的帮手。

Agriculture was another nonstarter in Australia, which is not only the driest continent but also the one with the most infertile soils. In addition, Australia is unique in that the overwhelming influence on climate over most of the continent is an irregular nonannual cycle, the ENSO (acronym for E1 Ni o Southern Oscillation), rather than the regular annual cycle of the seasons so familiar in most other parts of the world. Unpredictable severe droughts last for years, punctuated by equally unpredictable torrential rains and floods. Even today, with Eurasian crops and with trucks and railroads to transport produce, food production in Australia remains a risky business. Herds build up in good years, only to be killed off by drought. Any incipient farmers in Aboriginal Australia would have faced similar cycles in their own populations. If in good years they had settled in villages, grown crops, and produced babies, those large populations would have starved and died off in drought years, when the land could support far fewer people.

农业是澳大利亚的另一个毫无成功希望的行当,因为澳大利亚不但是最干旱的大陆,而且也是土壤最贫瘠的大陆。此外,澳大利亚还有一个方面也是独一无二的,这就是在这大陆的大部地区对气候产生压倒一切的影响的,是一种无规律的不是一年一度的循环——ENSO现象(ENSO是“厄尔尼诺向南移动”一词的首字母缩合词),而不是世界上其他大多数地区所熟悉的那种有规律的一年一度的季节循环。无法预测的严重干旱会持续几年,接着便是同样无法预测的倾盆大雨和洪水泛滥。即使在今天有了欧洲的农作物和用来运输农产品的卡车与铁路的情况下,粮食生产在澳大利亚也仍然是一种风险行业。年成好的时候,牧群繁衍增殖,而到发生干旱时便又死亡殆尽。澳大利亚早期土著农民中可能有人碰到过类似的循环。年成好的时候,他们便在村子里定居下来,种植庄稼,并生儿育女,而到了干旱的年头,这众多的人口便会因饥饿而大批死去,因为那一点土地只能养活比这少得多的人。

The other major obstacle to the development of food production in Australia was the paucity of domesticable wild plants. Even modern European plant geneticists have failed to develop any crop except macadamia nuts from Australia's native wild flora. The list of the world's potential prize cereals—the 56 wild grass species with the heaviest grains—includes only two Australian species, both of which rank near the bottom of the list (grain weight only 13 milligrams, compared with a whopping 40 milligrams for the heaviest grains elsewhere in the world). That's not to say that Australia had no potential crops at all, or that Aboriginal Australians would never have developed indigenous food production. Some plants, such as certain species of yams, taro, and arrowroot, are cultivated in southern New Guinea but also grow wild in northern Australia and were gathered by Aborigines there. As we shall see, Aborigines in the climatically most favorable areas of Australia were evolving in a direction that might have eventuated in food production. But any food production that did arise indigenously in Australia would have been limited by the lack of domesticable animals, the poverty of domesticable plants, and the difficult soils and climate.

澳大利亚发展粮食生产的另一个主要障碍是缺乏可以驯化的野生植物。甚至现代欧洲的植物遗传学家除了从澳大利亚当地的野生植物中培育出澳洲坚果外,其他就再也没有培育出什么作物来。在世界上潜在的最佳谷物——籽粒最重的56种禾本科植物——的名单中,只有两种出产在澳大利亚,而且这两种又几乎位居名单的最后(粒重仅为13毫克,而世界上其他地方最重籽粒的重量可达40毫克)。这并不是说,澳大利亚根本就没有任何潜在的作物,也不是说澳大利亚土著从未发展出本地的粮食生产。有些植物,如某些品种的薯蓣、芋艿和竹芋,是在新几内亚南部栽培的,但在澳大利亚北部也有野生的,是那里土著的采集对象。我们将要看到,在澳大利亚气候条件极其有利的地区,土著在沿着最终可能导致粮食生产的方向演进。但任何在澳大利亚本地出现的粮食生产,都可能会由于可驯化的动植物的缺乏以及土壤贫瘠和气候恶劣而受到限制。

Nomadism, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and minimal investment in shelter and possessions were sensible adaptations to Australia's ENSO-driven resource unpredictability. When local conditions deteriorated, Aborigines simply moved to an area where conditions were temporarily better. Rather than depending on just a few crops that could fail, they minimized risk by developing an economy based on a great variety of wild foods, not all of which were likely to fail simultaneously. Instead of having fluctuating populations that periodically outran their resources and starved, they maintained smaller populations that enjoyed an abundance of food in good years and a sufficiency in bad years.

流浪的生活、狩猎采集的生活方式以及对住所和财物的最小的投资,是因受澳大利亚厄尔尼诺南移影响而无法预知可以得到何种资源时的明智的适应行为。在当地条件恶化时,土著居民只是迁往一个暂时条件较好的地区。他们不是依赖几种可能歉收的作物,而是在丰富多样的野生食物的基础上发展经济,从而把风险减少到最低限度,因为所有这些野生食物不可能同时告乏。他们不是使人口在超过资源时挨饿而发生波动,而是维持较少的人口,这样在丰年时固然有丰富的食物可以享用,而在歉收时也不致有饥馁之虞。

The Aboriginal Australian substitute for food production has been termed “firestick farming.” The Aborigines modified and managed the surrounding landscape in ways that increased its production of edible plants and animals, without resorting to cultivation. In particular, they intentionally burned much of the landscape periodically. That served several purposes: the fires drove out animals that could be killed and eaten immediately; fires converted dense thickets into open parkland in which people could travel more easily; the parkland was also an ideal habitat for kangaroos, Australia's prime game animal; and the fires stimulated the growth both of new grass on which kangaroos fed and of fern roots on which Aborigines themselves fed.

澳大利亚土著居民用来代替粮食生产的是所谓的“火耕农业”。土著居民把周围的土地加以改造和整治,以提高可食用植物和动物的产量,而不用借助栽培和养殖。特别是,他们有意识地把周围很大一部分土地放火焚烧。这样做可以达到几个目的:火把立即可以杀来吃的动物赶出来;火把茂密的植丛变成了人们可以更容易通行的稀树草原;稀树草原也是澳大利亚主要的猎物袋鼠的理想的栖息地;火还促使袋鼠吃的嫩草和土著居民自己吃的蕨根的生长。

We think of Australian Aborigines as desert people, but most of them were not. Instead, their population densities varied with rainfall (because it controls the production of terrestrial wild plant and animal foods) and with abundance of aquatic foods in the sea, rivers, and lakes. The highest population densities of Aborigines were in Australia's wettest and most productive regions: the Murray-Darling river system of the Southeast, the eastern and northern coasts, and the southwestern corner. Those areas also came to support the densest populations of European settlers in modern Australia. The reason we think of Aborigines as desert people is simply that Europeans killed or drove them out of the most desirable areas, leaving the last intact Aboriginal populations only in areas that Europeans didn't want.

我们把澳大利亚土著看作是沙漠居民,但他们中的大多数不是这样的人。他们的人口密度随雨量的变化而变化(因为雨量决定着陆地野生动植物食物的产量),也随着江河湖海水产的丰富程度的不同而有所不同。土著人口密度最高的,是在最潮湿的、物产最丰富的地区:东南部的墨累-达令河水系、东部和北部海岸和西南角。这些地区也开始养活了现代澳大利亚人口最稠密的欧洲移民。我们所以把土著看作是沙漠居民是因为欧洲人或者把他们杀死,或者把他们从最合意的地区赶走,这样,最后的完好无损的土著人群体也只有在那些欧洲人不愿去的地区才能找到了。

Within the last 5,000 years, some of those productive regions witnessed an intensification of Aboriginal food-gathering methods, and a buildup of Aboriginal population density. Techniques were developed in eastern Australia for rendering abundant and starchy, but extremely poisonous, cycad seeds edible, by leaching out or fermenting the poison. The previously unexploited highlands of southeastern Australia began to be visited regularly during the summer, by Aborigines feasting not only on cycad nuts and yams but also on huge hibernating aggregations of a migratory moth called the bogong moth, which tastes like a roasted chestnut when grilled. Another type of intensified food-gathering activity that developed was the freshwater eel fisheries of the Murray-Darling river system, where water levels in marshes fluctuate with seasonal rains. Native Australians constructed elaborate systems of canals up to a mile and a half long, in order to enable eels to extend their range from one marsh to another. Eels were caught by equally elaborate weirs, traps set in dead-end side canals, and stone walls across canals with a net placed in an opening of the wall. Traps at different levels in the marsh came into operation as the water level rose and fell. While the initial construction of those “fish farms” must have involved a lot of work, they then fed many people. Nineteenth-century European observers found villages of a dozen Aboriginal houses at the eel farms, and there are archaeological remains of villages of up to 146 stone houses, implying at least seasonally resident populations of hundreds of people.

在过去5000年内,在那些物产丰富的地区中,有些地区发生了土著强化食物采集方法和土著人口密度增加的现象。在澳大利亚东部发明了一些技术,用滤掉毒素或使毒素发酵的办法,使大量的含有淀粉然而毒性极强的铁树种子变得可以食用。澳大利亚东南部以前未得到开发的高原地区,开始有土著在夏季经常来光顾,他们不但饱餐铁树的坚果和薯蓣,而且还大吃特吃大群潜伏不动的移栖飞蛾,这种蛾子叫做博贡蛾,烤了吃有炒栗子的味道。另一种逐步形成的强化了的食物采集活动,是墨累-达令河水系的鳗鲡养殖,这里沼泽中的水位随着季节性的雨量而涨落。当地的澳大利亚人修建了长达一英里半的复杂的沟渠系统,使鳗鲡的游动范围从一个沼泽扩大到另一个沼泽。捕捉鳗鲡用的是同样复杂的鱼梁、安放在尽头边沟上的渔栅和在墙洞里放上鱼网的垒在沟渠上的石墙。在沼泽中按不同水位安放的渔栅随着水位的涨落而发生作用。虽然当初修建这样的“养鱼场”必然是一项巨大的工程,但它们以后却养活了许多人。19世纪的一些欧洲观察者在鳗鲡养殖场旁边发现了由十几间土著的房屋组成的村庄,一些考古遗迹表明,有些村庄竟有多达146间的石屋,可见这些村庄的季节性居民至少有几百人之多。

Still another development in eastern and northern Australia was the harvesting of seeds of a wild millet, belonging to the same genus as the broomcorn millet that was a staple of early Chinese agriculture. The millet was reaped with stone knives, piled into haystacks, and threshed to obtain the seeds, which were then stored in skin bags or wooden dishes and finally ground with millstones. Several of the tools used in this process, such as the stone reaping knives and grindstones, were similar to the tools independently invented in the Fertile Crescent for processing seeds of other wild grasses. Of all the food-acquiring methods of Aboriginal Australians, millet harvesting is perhaps the one most likely to have evolved eventually into crop production.

澳大利亚东部和北部的另一项发展,是收获野生黍子的籽实,这是与中国早期农业的一种主要作物蜀黍同属的一种植物。黍子用石刀收割,堆成了垛,用摔打来脱粒,然后贮藏在皮袋或木盘里,最后用磨石磨碎。在这过程中使用的几种工具,如石头镰刀和磨石,类似于新月沃地为加工其他野生禾本科植物的种子而独立发明出来的那些工具。在澳大利亚土著所有的获取食物的方法中,收获黍子也许是最有可能最终演化为作物种植的一种方法。

Along with intensified food gathering in the last 5,000 years came new types of tools. Small stone blades and points provided more length of sharp edge per pound of tool than the large stone tools they replaced. Hatchets with ground stone edges, once present only locally in Australia, became widespread. Shell fishhooks appeared within the last thousand years.

同过去5000年中强化食物采集一起产生的,是一些新型的工具。小型的石片和三角石刀若按重量计算,每磅石器所提供的锋刃长度大于被它们所取代的大型石器。锋刃经过打磨的短柄石斧,一度在澳大利亚只有局部地区才有,这时已变得普遍了。在过去的几千年中,贝壳做的渔钩也出现了。

WHY DID AUSTRALIA not develop metal tools, writing, and politically complex societies? A major reason is that Aborigines remained hunter-gatherers, whereas, as we saw in Chapters 12–14, those developments arose elsewhere only in populous and economically specialized societies of food producers. In addition, Australia's aridity, infertility, and climatic unpredictability limited its hunter-gatherer population to only a few hundred thousand people. Compared with the tens of millions of people in ancient China or Mesoamerica, that meant that Australia had far fewer potential inventors, and far fewer societies to experiment with adopting innovations. Nor were its several hundred thousand people organized into closely interacting societies. Aboriginal Australia instead consisted of a sea of very sparsely populated desert separating several more productive ecological “islands,” each of them holding only a fraction of the continent's population and with interactions attenuated by the intervening distance. Even within the relatively moist and productive eastern side of the continent, exchanges between societies were limited by the 1,900 miles from Queensland's tropical rain forests in the northeast to Victoria's temperate rain forests in the southeast, a geographic and ecological distance as great as that from Los Angeles to Alaska.

为什么澳大利亚没有发展出金属工具、文字和复杂政治结构的社会?一个主要的原因是那里的土著仍然以狩猎采集为生,而我们已在第十二到第十四章看到,这些发展在别处只有在人口众多、经济专业化的粮食生产者社会里出现。此外,澳大利亚的干旱、贫瘠和气候变化无常,使它的狩猎采集人口只能有几十万人。同古代中国或中美洲的几千万人相比,那意味着澳大利亚潜在的发明者要少得多,采用借助新发明来进行试验的社会也少得多。它的几十万人也没有组成关系密切相互影响的社会。土著的澳大利亚是由一片人口十分稀少的沙漠组成的,沙漠把它分隔成几个物产比较丰富的生态“孤岛”,每一个这样的孤立地区只容纳这个大陆的一小部分人口,而且地区与地区之间的相互影响也由于间隔着的距离而减弱了。甚至在这个大陆东侧相对湿润和肥沃的地区内,社会之间的交流也由于从东北部的昆士兰热带雨林到东南部的维多利亚温带雨林之间的1900英里距离而受到了限制,这个距离无论在地理上还是在生态上都相当于从洛杉矶到阿拉斯加的距离。

Some apparent regional or continentwide regressions of technology in Australia may stem from the isolation and relatively few inhabitants of its population centers. The boomerang, that quintessential Australian weapon, was abandoned in the Cape York Peninsula of northeastern Australia. When encountered by Europeans, the Aborigines of southwestern Australia did not eat shellfish. The function of the small stone points that appear in Australian archaeological sites around 5,000 years ago remains uncertain: while an easy explanation is that they may have been used as spearpoints and barbs, they are suspiciously similar to the stone points and barbs used on arrows elsewhere in the world. If they really were so used, the mystery of bows and arrows being present in modern New Guinea but absent in Australia might be compounded: perhaps bows and arrows actually were adopted for a while, then abandoned, across the Australian continent. All these examples remind us of the abandonment of guns in Japan, of bows and arrows and pottery in most of Polynesia, and of other technologies in other isolated societies (Chapter 13).

在澳大利亚,地区性的或整个大陆的某些明显的退步现象,可能是由于它的一些人口中心与世隔绝和居民相对稀少所致。回飞镖是典型的澳大利亚武器,但却在澳大利亚东北部的约克角半岛被弃置不用。欧洲人碰到的澳大利亚西南部土著不吃有壳的水生动物。澳大利亚考古遗址中出现的大约5000年前的那种小型三角石刀究竟有什么用途,还仍然难以确定。虽然有一种方便的解释认为,它们可能被用作矛头和箭头倒钩,人们猜想它们和世界上其他地方用在箭上的三角石刀和箭头倒钩是同样的东西。如果这就是它们的用途,那么现代新几内亚有弓箭而澳大利亚却没有弓箭这个谜就更加难解了。也许在整个澳大利亚大陆曾经有一阵子采用过弓箭,但后来又放弃了。所有这些例子使我们想起了日本放弃过枪支,波利尼西亚大部分地区放弃过弓箭和陶器,以及其他一些与世隔绝的社会放弃过其他一些技术(第十三章)。

The most extreme losses of technology in the Australian region took place on the island of Tasmania, 130 miles off the coast of southeastern Australia. At Pleistocene times of low sea level, the shallow Bass Strait now separating Tasmania from Australia was dry land, and the people occupying Tasmania were part of the human population distributed continuously over an expanded Australian continent. When the strait was at last flooded around 10,000 years ago, Tasmanians and mainland Australians became cut off from each other because neither group possessed watercraft capable of negotiating Bass Strait. Thereafter, Tasmania's population of 4,000 hunter-gatherers remained out of contact with all other humans on Earth, living in an isolation otherwise known only from science fiction novels.

澳大利亚地区最大的技术损失发生于澳大利亚东南部海岸外130英里的塔斯马尼亚岛。今天的塔斯马尼亚岛与澳大利亚之间浅水的巴斯海峡,在更新世海平面低的那个时候还是干燥的陆地,居住在塔斯马尼亚岛上的人是先后分布在整个扩大了的澳大利亚的人口的一部分。当巴斯海峡在大约1万年前终于被海水淹没时,塔斯马尼亚人和澳大利亚大陆人之间的联系中断了,因为这两个群体都没有能够顺利渡过巴斯海峡的水运工具。从那以后,塔斯马尼亚岛上4000个以狩猎采集为生的人就失去了同地球上所有其他人类的联系,而生活在只有从科幻小说才能读到的一种与世隔绝的状态之中。

When finally encountered by Europeans in A.D. 1642, the Tasmanians had the simplest material culture of any people in the modern world. Like mainland Aborigines, they were hunter-gatherers without metal tools. But they also lacked many technologies and artifacts widespread on the mainland, including barbed spears, bone tools of any type, boomerangs, ground or polished stone tools, hafted stone tools, hooks, nets, pronged spears, traps, and the practices of catching and eating fish, sewing, and starting a fire. Some of these technologies may have arrived or been invented in mainland Australia only after Tasmania became isolated, in which case we can conclude that the tiny Tasmanian population did not independently invent these technologies for itself. Others of these technologies were brought to Tasmania when it was still part of the Australian mainland, and were subsequently lost in Tasmania's cultural isolation. For example, the Tasmanian archaeological record documents the disappearance of fishing, and of awls, needles, and other bone tools, around 1500 B.C. On at least three smaller islands (Flinders, Kangaroo, and King) that were isolated from Australia or Tasmania by rising sea levels around 10,000 years ago, human populations that would initially have numbered around 200 to 400 died out completely.

塔斯马尼亚人终于在公元1642年接触到了欧洲人,那时他们只是世界上物质文化最简单的民族。他们同大陆上的土著一样,也是没有金属工具的以狩猎采集为生的人。但他们也缺乏在大陆上已很普遍的许多技术和人工制品,包括有倒钩的矛、各种骨器、回飞镖、打磨的石器、有柄的石器、鱼钩、鱼网、有叉尖的矛、渔栅,以及捕鱼和吃鱼、缝纫和生火的习俗。在这些技术中,有些可能只是在塔斯马尼亚与大陆隔绝后引进大陆的,或者可能就是在大陆发明的。根据这种情况,我们可以断定,塔斯马尼亚的极少的人口并没有为自己独立地发明了这些技术。这些技术中还有一些是在塔斯马尼亚仍是澳大利亚大陆一部分的时候被带到塔斯马尼亚来的,不过随后又在塔斯马尼亚的文化孤立中失去了。例如,塔斯马尼亚的考古记录用文献证明了在公元前1500年左右渔场消失了,骨钻、骨针和其他骨器也消失了。至少还有3个较小的岛(弗林德斯岛、坎加鲁岛和金岛)在大约1万年前由于海平面上升而脱离了澳大利亚或塔斯马尼亚,在这3个岛上,原来可能有大约200人到400人的人口已全部灭绝了。

Tasmania and those three smaller islands thus illustrate in extreme form a conclusion of broad potential significance for world history. Human populations of only a few hundred people were unable to survive indefinitely in complete isolation. A population of 4,000 was able to survive for 10,000 years, but with significant cultural losses and significant failures to invent, leaving it with a uniquely simplified material culture. Mainland Australia's 300,000 hunter-gatherers were more numerous and less isolated than the Tasmanians but still constituted the smallest and most isolated human population of any of the continents. The documented instances of technological regression on the Australian mainland, and the example of Tasmania, suggest that the limited repertoire of Native Australians compared with that of peoples of other continents may stem in part from the effects of isolation and population size on the development and maintenance of technology—like those effects on Tasmania, but less extreme. By implication, the same effects may have contributed to differences in technology between the largest continent (Eurasia) and the next smaller ones (Africa, North America, and South America).

因此,塔斯马尼亚和这3个较小的岛屿,以极端的形式证明了一个对世界史具有广泛的潜在意义的结论。只有几百人的群体在完全与世隔绝的状态下是不可能无限期地生存下去的。一个有4000人的群体能够生存1万年,但在文化上要失去相当多的东西,同时也引人注目地没有什么发明创造,剩下的只是一种无比简单的文化。澳大利亚大陆上的30万以狩猎采集为生的人,在数目上比塔斯马尼亚人多,也不像塔斯马尼亚人那样与世隔绝,但它的人口仍然是各大陆中最少的,也是各大陆中最与世隔绝的。关于澳大利亚大陆有文献证明的技术退步的例子和关于塔斯马尼亚的这个例子表明,同其他各大陆民族的全部业绩相比,澳大利亚本地人的有限业绩,可能一部分来自与世隔绝状态和由于人口太少而对技术的发展与保持所产生的影响——就像对塔斯马尼亚所产生的那些影响一样,只是影响的程度没有那么大罢了。不言而喻,这种影响可能就是最大的大陆(欧亚大陆)与依次较小的大陆(非洲、北美洲和南美洲)之间在技术上产生差异的原因。

WHY DIDN'T MORE-ADVANCED technology reach Australia from its neighbors, Indonesia and New Guinea? As regards Indonesia, it was separated from northwestern Australia by water and was very different from it ecologically. In addition, Indonesia itself was a cultural and technological backwater until a few thousand years ago. There is no evidence of any new technology or introduction reaching Australia from Indonesia, after Australia's initial colonization 40,000 years ago, until the dingo appeared around 1500 B.C.

为什么较先进的技术没有从邻近的印度尼西亚和新几内亚传入澳大利亚?就印度尼西亚而言,它与澳大利亚西北部隔着大海,生态环境差异很大。此外,直到几千年前,印度尼西亚本身也是一个文化和技术落后地区。没有任何证据可以证明,从4万年前澳大利亚最早有人定居时起直到公元前1500年左右澳洲野犬出现时止,有任何新技术或动植物新品种是从印度尼西亚传入澳大利亚的。

The dingo reached Australia at the peak of the Austronesian expansion from South China through Indonesia. Austronesians succeeded in settling all the islands of Indonesia, including the two closest to Australia—Timor and Tanimbar (only 275 and 205 miles from modern Australia, respectively). Since Austronesians covered far greater sea distances in the course of their expansion across the Pacific, we would have to assume that they repeatedly reached Australia, even if we did not have the evidence of the dingo to prove it. In historical times northwestern Australia was visited each year by sailing canoes from the Macassar district on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi (Celebes), until the Australian government stopped the visits in 1907. Archaeological evidence traces the visits back until around A.D. 1000, and they may well have been going on earlier. The main purpose of the visits was to obtain sea cucumbers (also known as bêche-demer or trepang), starfish relatives exported from Macassar to China as a reputed aphrodisiac and prized ingredient of soups.

澳洲野犬在南岛人对外扩张的极盛时期从中国华南通过印度尼西亚传入澳大利亚。南岛人成功地在印度尼西亚各个岛屿定居下来,其中包括离澳大利亚最近的两个岛屿——帝汶岛和丹宁巴群岛(分别距离现代澳大利亚仅为275英里和205英里)。由于南岛人在其横渡太平洋进行扩张的过程中走过了非常远的海上距离,因此我们可能不得不假定他们曾多次到过澳大利亚,即使我们没有澳洲野犬这个证据来证明这一点。在历史上,每年都有一些张帆行驶的独木舟从印度尼西亚的苏拉威西岛(西里伯斯岛)的望加锡地区到澳大利亚西北部来访问,直到澳大利亚政府于1907年禁止了这种造访。考古证据表明,这种访问可以追溯到公元1000年左右,很有可能更早。这些访问的主要目的是要得到海参。海参是海星的亲缘动物,作为一种著名的催欲剂和珍贵的汤料从望加锡出口到中国。

Naturally, the trade that developed during the Macassans' annual visits left many legacies in northwestern Australia. The Macassans planted tamarind trees at their coastal campsites and sired children by Aboriginal women. Cloth, metal tools, pottery, and glass were brought as trade goods, though Aborigines never learned to manufacture those items themselves. Aborigines did acquire from the Macassans some loan words, some ceremonies, and the practices of using dugout sailing canoes and smoking tobacco in pipes.

当然,在望加锡人一年一度的访问期间发展起来的贸易,在澳大利亚西北部留下了许多遗产。望加锡人在他们的海岸营地种下了罗望子树,并同土著妇女生儿育女。布、金属工具、陶器和玻璃被带来作为贸易物品,然而土著居民却没有学会自己来制造这些物品。土著居民从望加锡人那里学到了一些外来词、一些礼仪以及使用张帆行驶的独木舟和用烟斗吸烟的习俗。

But none of these influences altered the basic character of Australian society. More important than what happened as a result of the Macassan visits is what did not happen. The Macassans did not settle in Australia—undoubtedly because the area of northwestern Australia facing Indonesia is much too dry for Macassan agriculture. Had Indonesia faced the tropical rain forests and savannas of northeastern Australia, the Macassans could have settled, but there is no evidence that they ever traveled that far. Since the Macassans thus came only in small numbers and for temporary visits and never penetrated inland, just a few groups of Australians on a small stretch of coast were exposed to them. Even those few Australians got to see only a fraction of Macassan culture and technology, rather than a full Macassan society with rice fields, pigs, villages, and workshops. Because the Australians remained nomadic hunter-gatherers, they acquired only those few Macassan products and practices compatible with their lifestyle. Dugout sailing canoes and pipes, yes; forges and pigs, no.

但这些影响都没有能改变澳大利亚社会的基本特点。由于望加锡人的到来,一些事情发生了,但更为重要的却是没有发生的事。这就是望加锡人没有在澳大利亚定居下来——这无疑是因为印度尼西亚对面的澳大利亚西北部地区过于干旱,不适于发展望加锡的农业。如果印度尼西亚的对面是澳大利亚东北部的热带雨林或热带草原,望加锡人可能已定居下来了,但没有证据表明他们到过那么远的地方。既然只有很少的望加锡人到这里来作短暂停留而从未深入内陆腹地,他们所能接触到的就只有生活在沿海一小片地区的几个澳大利亚人群体。甚至这少数澳大利亚人也只是看到一小部分的望加锡文化和技术,而不是一个有稻田、猪、村庄和作坊的全面的望加锡社会。由于澳大利亚人仍然是四处流浪的以狩猎采集为生的人,他们所得到的就只有那几种适合他们的生活方式的望加锡产品和习俗。张帆行驶的独木舟和烟斗,得到了;锻铁炉和猪,没有得到。

Apparently much more astonishing than Australians' resistance to Indonesian influence is their resistance to New Guinea influence. Across the narrow ribbon of water known as Torres Strait, New Guinea farmers who spoke New Guinea languages and had pigs, pottery, and bows and arrows faced Australian hunter-gatherers who spoke Australian languages and lacked pigs, pottery, and bows and arrows. Furthermore, the strait is not an open-water barrier but is dotted with a chain of islands, of which the largest (Muralug Island) lies only 10 miles from the Australian coast. There were regular trading visits between Australia and the islands, and between the islands and New Guinea. Many Aboriginal women came as wives to Muralug Island, where they saw gardens and bows and arrows. How was it that those New Guinea traits did not get transmitted to Australia?

比澳大利亚人抵制印度尼西亚的影响显然更加令人惊异的是他们抵制新几内亚的影响。说新几内亚语并且有猪、有陶器和弓箭的新几内亚农民,在叫做托雷斯海峡的一衣带水的对面就是说澳大利亚语、没有猪、没有陶器和弓箭的澳大利亚狩猎采集族群。而且,托雷斯海峡不是一道水面开阔的天然屏障,而是星星点点地散布着一系列岛屿,其中最大的一个岛(穆拉勒格岛)距离澳大利亚海岸不过10英里之遥。澳大利亚和这些岛屿之间以及这些岛屿和新几内亚之间都有经常的贸易往来。许多土著妇女嫁到了穆拉勒格岛,她们在岛上看到了园圃和弓箭。新几内亚的这些特点竟没有传到澳大利亚来,这是怎么一回事呢?

This cultural barrier at Torres Strait is astonishing only because we may mislead ourselves into picturing a full-fledged New Guinea society with intensive agriculture and pigs 10 miles off the Australian coast. In reality, Cape York Aborigines never saw a mainland New Guinean. Instead, there was trade between New Guinea and the islands nearest New Guinea, then between those islands and Mabuiag Island halfway down the strait, then between Mabuiag Island and Badu Island farther down the strait, then between Badu Island and Muralug Island, and finally between Muralug and Cape York.

托雷斯海峡的这种文化障碍之所以令人惊讶,仅仅是因为我们可能错误地使自己构想了澳大利亚海岸外10英里处的一个有集约型农业和猪的成熟的新几内亚社会。事实上,约克角土著从未见过任何一个大陆新几内亚人。不过,在新几内亚与离它最近的岛屿之间、然后在这些岛屿与托雷斯海峡中途的马布伊格岛之间、再后在巴杜岛与穆拉勒格岛之间、最后又在穆拉勒格岛与约克角之间,都有贸易关系。

New Guinea society became attenuated along that island chain. Pigs were rare or absent on the islands. Lowland South New Guineans along Torres Strait practiced not the intensive agriculture of the New Guinea highlands but a slash-and-burn agriculture with heavy reliance on seafoods, hunting, and gathering. The importance of even those slash-and-burn practices decreased from southern New Guinea toward Australia along the island chain. Muralug Island itself, the island nearest Australia, was dry, marginal for agriculture, and supported only a small human population, which subsisted mainly on seafood, wild yams, and mangrove fruits.

沿着这个岛群向前,新几内亚的社会就显得每况愈下。在这些岛上猪很少或者根本没有。沿托雷斯海峡的新几内亚南部低地居民不从事新几内亚高原地区的那种集约型农业,而是刀耕火种,主要靠海产、打猎和采集为生。甚至这种刀耕火种的习惯,从新几内亚南部沿着这个岛群到澳大利亚,也变得越来越不重要了。离澳大利亚最近的穆拉勒格岛本身也因干旱而不适于农业,所以只能养活很少的人口,而这些人主要靠海产、野生薯蓣和红树果子来维持生存。

The interface between New Guinea and Australia across Torres Strait was thus reminiscent of the children's game of telephone, in which children sit in a circle, one child whispers a word into the ear of the second child, who whispers what she thinks she has just heard to the third child, and the word finally whispered by the last child back to the first child bears no resemblance to the initial word. In the same way, trade along the Torres Strait islands was a telephone game that finally presented Cape York Aborigines with something very different from New Guinea society. In addition, we should not imagine that relations between Muralug Islanders and Cape York Aborigines were an uninterrupted love feast at which Aborigines eagerly sopped up culture from island teachers. Trade instead alternated with war for the purposes of head-hunting and capturing women to become wives.

因此,新几内亚和澳大利亚隔着托雷斯海峡的相互联系使人想起了小孩子的传话游戏:孩子们坐成一圈,一个孩子凑着第二个孩子的耳朵把一个词轻轻地说给他听,第二个孩子又把他认为他听到的那个词轻轻地说给第三个孩子听,这样,最后一个孩子最后轻轻地再说给第一个孩子听的那词就同原来的那个词毫不相干。同样,沿托雷斯海峡诸岛进行的贸易也是一种传话游戏,最后到了约克角土著手中的是一种与新几内亚社会完全不同的东西。此外,我们也不应把穆拉勒格岛民同约克角土著之间的关系想像成一种从未间断的友好聚餐,土著迫不及待地从海岛老师那里汲取文化。实际上,贸易和战争交替进行,而战争的目的则是割取敌人的首级做战利品和把女人捉来做老婆。

Despite the dilution of New Guinea culture by distance and war, some New Guinea influence did manage to reach Australia. Intermarriage carried New Guinea physical features, such as coiled rather than straight hair, down the Cape York Peninsula. Four Cape York languages had phonemes unusual for Australia, possibly because of the influence of New Guinea languages. The most important transmissions were of New Guinea shell fishhooks, which spread far into Australia, and of New Guinea outrigger canoes, which spread down the Cape York Peninsula. New Guinea drums, ceremonial masks, funeral posts, and pipes were also adopted on Cape York. But Cape York Aborigines did not adopt agriculture, in part because what they saw of it on Muralug Island was so watered-down. They did not adopt pigs, of which there were few or none on the islands, and which they would in any case have been unable to feed without agriculture. Nor did they adopt bows and arrows, remaining instead with their spears and spear-throwers.

尽管新几内亚文化由于距离和战争而受到了削弱,但新几内亚的某种影响还是到达了澳大利亚。通婚给约克角半岛南部带来了某些新几内亚体貌特征,如鬈发而不是直发。约克角的4种语言有澳大利亚罕见的音素,这可能是由于受到新几内亚一些语言的影响。传进来的最重要的东西中,有澳大利亚内陆普遍使用的新几内亚贝壳鱼钩,还有在约克角半岛南部流行的带有舷外浮材的新几内亚独木舟。新几内亚的鼓、举行仪式时戴的面具、葬礼柱和烟斗,也在约克角被采用了。但约克角的土著并没有采用农业,这一部分是因为他们在穆拉勒格所看到的农业已经微不足道了。他们也没有选择养猪,因为在那些岛上猪很少或者根本没有,也因为无论如何没有农业就不可能养猪。他们也没有采用弓箭,而是仍然使用他们的长矛和掷矛器。

Australia is big, and so is New Guinea. But contact between those two big landmasses was restricted to those few small groups of Torres Strait islanders with a highly attenuated New Guinea culture, interacting with those few small groups of Cape York Aborigines. The latter groups' decisions, for whatever reason, to use spears rather than bows and arrows, and not to adopt certain other features of the diluted New Guinea culture they saw, blocked transmission of those New Guinea cultural traits to all the rest of Australia. As a result, no New Guinea trait except shell fishhooks spread far into Australia. If the hundreds of thousands of farmers in the cool New Guinea highlands had been in close contact with the Aborigines in the cool highlands of southeastern Australia, a massive transfer of intensive food production and New Guinea culture to Australia might have followed. But the New Guinea highlands are separated from the Australian highlands by 2,000 miles of ecologically very different landscape. The New Guinea highlands might as well have been the mountains of the moon, as far as Australians' chances of observing and adopting New Guinea highland practices were concerned.

澳大利亚很大,新几内亚也很大。但这两个巨大陆块之间的接触,只限于几小批只有很少新几内亚文化的托雷斯海峡岛民与几小批约克角土著的相互影响。约克角土著群体不管出于什么原因而决定使用长矛而不使用弓箭,以及不采纳他们所看到的已经削弱了的新几内亚文化的某些其他特点,从而妨碍了新几内亚这些文化特点向澳大利亚其余所有地区的传播。结果,除了贝壳鱼钩,再没有任何其他新几内亚文化特点传播到澳大利亚腹地了。如果新几内亚气候凉爽的高原地区的几十万农民与澳大利亚东南部气候凉爽的高原地区的土著有过密切的接触,那么,集约型粮食生产和新几内亚文化向澳大利亚的大规模传播就可能接踵而来。但新几内亚高原地区同澳大利亚高原地区之间隔着2000英里的生态环境差异很大的地带。就澳大利亚能有多少机会看到并采用新几内亚高原地区的做法这一点来说,新几内亚高原地区不妨说就是月亮里的山。

In short, the persistence of Stone Age nomadic hunter-gatherers in Australia, trading with Stone Age New Guinea farmers and Iron Age Indonesian farmers, at first seems to suggest singular obstinacy on the part of Native Australians. On closer examination, it merely proves to reflect the ubiquitous role of geography in the transmission of human culture and technology.

总之,虽然澳大利亚石器时代的四处流浪的狩猎采集族群与石器时代的新几内亚农民及铁器时代的印度尼西亚农民都有过贸易往来,但他们始终保持自己的生活方式不变,这初看起来似乎是表明了澳大利亚土著出奇的顽固不化。但更进一步的考察就可发现,这不过是反映了地理条件在人类文化和技术传播中的无处不在的作用。

IT REMAINS FOR us to consider the encounters of New Guinea's and Australia's Stone Age societies with Iron Age Europeans. A Portuguese navigator “discovered” New Guinea in 1526, Holland claimed the western half in 1828, and Britain and Germany divided the eastern half in 1884. The first Europeans settled on the coast, and it took them a long time to penetrate into the interior, but by 1960 European governments had established political control over most New Guineans.

我们仍然需要考虑一下新几内亚和澳大利亚石器时代的社会同铁器时代的欧洲人相遭遇的情况。1526年,一个葡萄牙航海家“发现了”新几内亚;1828年,荷兰宣布对它的西半部拥有主权;1884年,英国和德国瓜分了它的东半部。第一批欧洲人在海岸地区定居下来,他们花了很长时间才深入内陆,但到1960年,欧洲人的政府已经对新几内亚的大部分地区建立了政治控制。

The reasons that Europeans colonized New Guinea, rather than vice versa, are obvious. Europeans were the ones who had the oceangoing ships and compasses to travel to New Guinea; the writing systems and printing presses to produce maps, descriptive accounts, and administrative paperwork useful in establishing control over New Guinea; the political institutions to organize the ships, soldiers, and administration; and the guns to shoot New Guineans who resisted with bow and arrow and clubs. Yet the number of European settlers was always very small, and today New Guinea is still populated largely by New Guineans. That contrasts sharply with the situation in Australia, the Americas, and South Africa, where European settlement was numerous and lasting and replaced the original native population over large areas. Why was New Guinea different?

欧洲人到新几内亚去殖民,而不是新几内亚人到欧洲来殖民,其原因是显而易见的。欧洲人有远洋船只和罗盘,可以用来帮助他们前往新几内亚;他们有书写系统和印刷机,可以用来印刷地图、描述性的报告和有助于建立对新几内亚的控制的行政文书;他们有政治机构,可以用来组织船只、士兵和行政管理;他们还有枪炮,可以用来向以弓箭和棍棒进行抵抗的新几内亚人射击。然而,欧洲移民的人数始终很少,今天新几内亚的人口仍然以新几内亚人为主。这同澳大利亚、美洲和南非的情况形成了鲜明的对比,因为在那些地方,欧洲人的殖民地数量多、时间久,在广大地区内取代了原来的土著人口。为什么新几内亚却不同呢?

A major factor was the one that defeated all European attempts to settle the New Guinea lowlands until the 1880s: malaria and other tropical diseases, none of them an acute epidemic crowd infection as discussed in Chapter 11. The most ambitious of those failed lowland settlement plans, organized by the French marquis de Rays around 1880 on the nearby island of New Ireland, ended with 930 out of the 1,000 colonists dead within three years. Even with modern medical treatments available today, many of my American and European friends in New Guinea have been forced to leave because of malaria, hepatitis, or other diseases, while my own health legacy of New Guinea has been a year of malaria and a year of dysentery.

一个主要的因素在19世纪80年代之前挫败了所有欧洲人想要在新几内亚低地地区定居的企图:这个因素就是疟疾和其他热带疾病,虽然其中没有一种是第十一章讨论的那种急性群众性流行传染病。在这些未能实现的对低地地区殖民的计划中,最雄心勃勃的计划是法国侯爵德雷伊于1880年左右在附近的新爱尔兰岛组织的,结果1000个殖民者在不到3年的时间里死掉了930人。即使在今天能够得到现代医药治疗的情况下,我的许多美国朋友和欧洲朋友还是由于疟疾、肝炎和其他疾病而被迫离开,而新几内亚留给我个人的健康遗产则是我得了一年的疟疾和一年的痢疾。

As Europeans were being felled by New Guinea lowland germs, why were Eurasian germs not simultaneously felling New Guineans? Some New Guineans did become infected, but not on the massive scale that killed off most of the native peoples of Australia and the Americas. One lucky break for New Guineans was that there were no permanent European settlements in New Guinea until the 1880s, by which time public health discoveries had made progress in bringing smallpox and other infectious diseases of European populations under control. In addition, the Austronesian expansion had already been bringing a stream of Indonesian settlers and traders to New Guinea for 3,500 years. Since Asian mainland infectious diseases were well established in Indonesia, New Guineans thereby gained long exposure and built up much more resistance to Eurasian germs than did Aboriginal Australians.

在欧洲人正在被新几内亚低地地区的病菌击倒的时候,为什么欧亚大陆的病菌没有同时击倒新几内亚人?有些新几内亚人的确受到了传染,但并没有达到杀死澳大利亚和美洲大多数土著那样大的规模。对新几内亚人来说,幸运的是在19世纪80年代前新几内亚没有永久性的欧洲人殖民地,而到了这个时候,公共卫生方面的发现已经在控制欧洲人口中的天花和其他传染病方面取得了进展。此外,南岛人的扩张在3500年中已经把一批又一批的印度尼西亚的移民和商人带到了新几内亚。由于亚洲大陆的一些传染病已在印度尼西亚滋生繁衍,新几内亚人因此而长期地接触到这些疾病,所以逐渐形成了比澳大利亚土著多得多的抵抗力。

The sole part of New Guinea where Europeans do not suffer from severe health problems is the highlands, above the altitudinal ceiling for malaria. But the highlands, already occupied by dense populations of New Guineans, were not reached by Europeans until the 1930s. By then, the Australian and Dutch colonial governments were no longer willing to open up lands for white settlement by killing native people in large numbers or driving them off their lands, as had happened during earlier centuries of European colonialism.

在新几内亚,欧洲人不为严重的健康问题而苦恼的唯一地区,是超过发生疟疾的最大海拔高度的高原地区。但高原地区已为人口稠密的新几内亚人所占据,欧洲人直到20世纪30年代才到达这里。到这时,澳大利亚政府和荷兰殖民政府不再愿意像以前几个世纪欧洲殖民主义时期那样,通过大批杀死土著族群或把他们赶出他们的土地,来开放土地供建立白人殖民地之用。

The remaining obstacle to European would-be settlers was that European crops, livestock, and subsistence methods do poorly everywhere in the New Guinea environment and climate. While introduced tropical American crops such as squash, corn, and tomatoes are now grown in small quantities, and tea and coffee plantations have been established in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, staple European crops, like wheat, barley, and peas, have never taken hold. Introduced cattle and goats, kept in small numbers, suffer from tropical diseases, just as do European people themselves. Food production in New Guinea is still dominated by the crops and agricultural methods that New Guineans perfected over the course of thousands of years.

对想要成为移民的欧洲人来说,剩下的一个障碍是,在新几内亚的环境和气候条件下,欧洲的作物、牲口和生存方法没有一个地方取得成功。虽然引进的美洲热带作物如南瓜、玉米和马铃薯现在已有少量种植,茶和咖啡种植园也已在巴布亚新几内亚高原地区建立起来,但欧洲的主要作物如小麦、大麦和豌豆一直未能占主导地位。引进的牛和山羊也是少量饲养,它们同欧洲人一样,也为一些热带疾病所折磨。在新几内亚的粮食生产中占主导地位的仍是新几内亚人在过去几千年中予以完善的那些作物和农业方法。

All those problems of disease, rugged terrain, and subsistence contributed to Europeans' leaving eastern New Guinea (now the independent nation of Papua New Guinea) occupied and governed by New Guineans, who nevertheless use English as their official language, write with the alphabet, live under democratic governmental institutions modeled on those of England, and use guns manufactured overseas. The outcome was different in western New Guinea, which Indonesia took over from Holland in 1963 and renamed Irian Jaya province. The province is now governed by Indonesians, for Indonesians. Its rural population is still overwhelmingly New Guinean, but its urban population is Indonesian, as a result of government policy aimed at encouraging Indonesian immigration. Indonesians, with their long history of exposure to malaria and other tropical diseases shared with New Guineans, have not faced as potent a germ barrier as have Europeans. They are also better prepared than Europeans for subsisting in New Guinea, because Indonesian agriculture already included bananas, sweet potatoes, and some other staple crops of New Guinea agriculture. The ongoing changes in Irian Jaya represent the continuation, backed by a centralized government's full resources, of the Austronesian expansion that began to reach New Guinea 3,500 years ago. Indonesians are modern Austronesians.

所有这些疾病、崎岖的地形和生存问题,是使欧洲人离开新几内亚东部(现在的独立国家巴布亚新几内亚)的部分原因,这个地区为新几内亚人所占有和管理,不过他们却把英语作为他们的官方语言,用英语字母书写,生活在以英国为模本的民主政治制度之下,并使用在海外生产的枪炮。在新几内亚西部结果就不一样了,印度尼西亚于1963年从荷兰人手中接管了这个地区,并被更名为伊里安查亚省。这个省现在为印度尼西亚人治理和享有。它的农村人口的绝大多数仍是新几内亚人,但由于政府鼓励印度尼西亚移民的政策,它的城市人口是印度尼西亚人。由于长期接触疟疾和其他一些与新几内亚人共有的热带疾病,印度尼西亚人没有像欧洲人那样碰到了一道强大的病菌障碍。对于在新几内亚生存问题,他们也比欧洲人有更充分的思想准备,因为印度尼西亚的农业已经包括了香蕉、甘薯和其他一些新几内亚农业的主要作物。伊里安查亚省正在发生的变革,代表了在中央政府的全力支持下继续进行3500年前开始到达新几内亚的南岛人的扩张。印度尼西亚人就是现代的南岛人。

EUROPEANS COLONIZED AUSTRALIA, rather than Native Australians colonizing Europe, for the same reasons that we have just seen in the case of New Guinea. However, the fates of New Guineans and of Aboriginal Australians were very different. Today, Australia is populated and governed by 20 million non-Aborigines, most of them of European descent, plus increasing numbers of Asians arriving since Australia abandoned its previous White Australia immigration policy in 1973. The Aboriginal population declined by 80 percent, from around 300,000 at the time of European settlement to a minimum of 60,000 in 1921. Aborigines today form an underclass of Australian society. Many of them live on mission stations or government reserves, or else work for whites as herdsmen on cattle stations. Why did Aborigines fare so much worse than New Guineans?

欧洲人在澳大利亚殖民,而不是澳大利亚土著在欧洲殖民,其原因同我们刚才在新几内亚这个例子上看到的一样。然而,新几内亚人和澳大利亚土著的命运却是不同的。今天的澳大利亚为2000万非土著所居住和管理,他们大多数都是欧洲人的后裔,同时由于澳大利亚于1973年放弃了先前的白人澳大利亚的移民政策,有越来越多的亚洲人来到了澳大利亚。土著人口减少了80%,从欧洲殖民地时代的30万人左右下降到1921年最低点6万人。今天的土著构成了澳大利亚社会的最底层。他们有许多人住在布道站或政府保留地里,或者为白人放牧而住在畜牧站里。为什么土著的境况比新几内亚人差得这么多?