CHAPTER 16

第十六章

HOW CHINA BECAME CHINESE

中国是怎样成为中国人的中国的

IMMIGRATION, AFFIRMATIVE ACTION, MULTILINGUALISM, ethnic diversity—my state of California was among the pioneers of these controversial policies and is now pioneering a backlash against them. A glance into the classrooms of the Los Angeles public school system, where my sons are being educated, fleshes out the abstract debates with the faces of children. Those children represent over 80 languages spoken in the home, with English-speaking whites in the minority. Every single one of my sons' playmates has at least one parent or grandparent who was born outside the United States; that's true of three of my own sons' four grandparents. But immigration is merely restoring the diversity that America held for thousands of years. Before European settlement, the mainland United States was home to hundreds of Native American tribes and languages and came under control of a single government only within the last hundred years.

外来移民、鼓励雇用少数民族成员及妇女的赞助性行动、多种语言的使用、种族的多样性——我生活的加利福尼亚州曾是这些有争议的政策的倡导者之一,现在它又在带头强烈反对这些政策。我的儿子在洛杉矶公立学校就读,只要向这些学校的教室里看上一眼,你就会发现关于这些政策的抽象辩论就像这些孩子们的脸一样具体而实际。这些孩子代表了在家里说的80多种语言,而说英语的白人却成了少数。我的儿子们的每一个在一起玩耍的伙伴的父母或祖父母中,至少有一人是在美国以外的地方出生的;我自己的儿子的祖父母和外祖父母4人中有3个不是出生在美国。不过,外来移民仅仅是恢复美洲保持了数千年之久的种族多样性而已。在欧洲人定居前,美国大陆是数以百计的印第安部落和语言的发源地,只是在最近的几百年内才受到单一政府的控制。

In these respects the United States is a thoroughly “normal” country. All but one of the world's six most populous nations are melting pots that achieved political unification recently, and that still support hundreds of languages and ethnic groups. For example, Russia, once a small Slavic state centered on Moscow, did not even begin its expansion beyond the Ural Mountains until A.D. 1582. From then until the 19th century, Russia proceeded to swallow up dozens of non-Slavic peoples, many of which retain their original language and cultural identity. Just as American history is the story of how our continent's expanse became American, Russia's history is the story of how Russia became Russian. India, Indonesia, and Brazil are also recent political creations (or re-creations, in the case of India), home to about 850, 670, and 210 languages, respectively.

在这些方面,美国是一个完全“正常的”国家。在世界上人口最多的6个国家中,除一国外,其余都是不久前实现政治统一的民族大熔炉,仍然保持着几百种语言和种族群体。例如,俄国曾是一个以莫斯科为中心的小小的斯拉夫国家,直到公元1582年它才开始向乌拉尔山脉以外的地区扩张。从那时起直到19世纪,俄国开始并吞了几十个非斯拉夫民族,其中许多民族仍然保有自己原来的语言和文化特性。正如美国的历史就是关于我们大陆的广大地区如何成为美国人的地区的故事一样,俄国的历史就是关于俄国如何成为俄国人的俄国的故事。印度、印度尼西亚和巴西也是不久前的政治创造(或者就印度的情况而言是政治再创造),它们分别是大约850种、670种和210种语言的发源地。

The great exception to this rule of the recent melting pot is the world's most populous nation, China. Today, China appears politically, culturally, and linguistically monolithic, at least to laypeople. It was already unified politically in 221 B.C. and has remained so for most of the centuries since then. From the beginnings of literacy in China, it has had only a single writing system, whereas modern Europe uses dozens of modified alphabets. Of China's 1.2 billion people, over 800 million speak Mandarin, the language with by far the largest number of native speakers in the world. Some 300 million others speak seven other languages as similar to Mandarin, and to each other, as Spanish is to Italian. Thus, not only is China not a melting pot, but it seems absurd to ask how China became Chinese. China has been Chinese, almost from the beginnings of its recorded history.

近代民族大熔炉这一普遍现象的重大例外是世界上人口最多的国家——中国。今天的中国无论在政治上、文化上或是语言上似乎都是一个大一统的国家,至少在外行人看来是这样。它在公元前221年就已在政治上统一了,并从那时起在大多数世纪中一直保持着统一的局面。自从中国开始有文字以来,它始终只有一个书写系统,而现代欧洲则在使用几十种经过修改的字母。在中国的12亿人中有8亿多人讲官话,这是世界上作为本族语使用的人数最多的语言。还有大约3亿人讲另外7种语言,这些语言和官话的关系以及它们彼此间的关系,就像西班牙语和意大利语的关系一样。因此,不但中国不是一个民族大熔炉,而且连提出中国是怎样成为中国人的中国这个问题都似乎荒谬可笑。中国一直就是中国人的,几乎从它的有文字记载的历史的早期阶段就是中国人的了。

We take this seeming unity of China so much for granted that we forget how astonishing it is. One reason why we should not have expected such unity is genetic. While a coarse racial classification of world peoples lumps all Chinese people as so-called Mongoloids, that category conceals much more variation than the differences between Swedes, Italians, and Irish within Europe. In particular, North and South Chinese are genetically and physically rather different: North Chinese are most similar to Tibetans and Nepalese, while South Chinese are similar to Vietnamese and Filipinos. My North and South Chinese friends can often distinguish each other at a glance by physical appearance: the North Chinese tend to be taller, heavier, paler, with more pointed noses, and with smaller eyes that appear more “slanted” (because of what is termed their epicanthic fold).

对于中国的这种表面上的统一,我们过分信以为真,以致忘记了这多么令人惊讶。我们本来就不应该指望有这种统一,这里有一个遗传上的原因。虽然有一种从人种上对世界各民族的不精确的分类法把所有中国人统统归入蒙古人种,但这种分类所掩盖的差异比欧洲的瑞典人、意大利人和爱尔兰人之间的差异大得多。尤其是,中国的华北人和华南人在遗传上和体质上都存在相当大的差异:华北人最像西藏人和尼泊尔人,而华南人则像越南人和菲律宾人。我的华北朋友和华南朋友常常一眼就能从体貌上把彼此区别开来:华北人往往个子较高,身体较重,鼻子较尖,眼睛较小,眼角更显“上斜”(由于所谓的内眦赘皮关系)。

North and South China differ in environment and climate as well: the north is drier and colder; the south, wetter and hotter. Genetic differences arising in those differing environments imply a long history of moderate isolation between peoples of North and South China. How did those peoples nevertheless end up with the same or very similar languages and cultures?

中国的华北和华南在环境和气候方面也有差异:北方比较干燥也比较冷;南方比较潮湿也比较热。在这些不同的环境里产生的遗传差异,说明华北人和华南人之间有过适度隔离的漫长历史。但这些人到头来却又有着相同的或十分相似的语言和文化,这又是怎么一回事呢?

China's apparent linguistic near-unity is also puzzling in view of the linguistic disunity of other long-settled parts of the world. For instance, we saw in the last chapter that New Guinea, with less than one-tenth of China's area and with only about 40,000 years of human history, has a thousand languages, including dozens of language groups whose differences are far greater than those among the eight main Chinese languages. Western Europe has evolved or acquired about 40 languages just in the 6,000–8,000 years since the arrival of Indo-European languages, including languages as different as English, Finnish, and Russian. Yet fossils attest to human presence in China for over half a million years. What happened to the tens of thousands of distinct languages that must have arisen in China over that long time span?

世界上其他一些地方虽然有人长期定居,但语言并不统一,从这一点来看,中国在语言上明显的近乎统一也就令人费解了。例如,我们在上一章看到,新几内亚的面积不到中国的十分之一,它的人类历史也只有大约4万年,但它却有1000种语言,包括几十个语族,这些语族之间的差异要比中国8种主要语言之间的差异大得多。西欧在印欧语传入后的6000—8000年中,逐步形成或获得了大约40种语言,包括像英语、芬兰语和俄语这样不同的语言。然而,有化石证明,50多万年前中国便已有人类存在了。在这样长的时间里,必然会在中国产生的那成千上万种不同的语言到哪里去了?

These paradoxes hint that China too was once diverse, as all other populous nations still are. China differs only by having been unified much earlier. Its “Sinification” involved the drastic homogenization of a huge region in an ancient melting pot, the repopulation of tropical Southeast Asia, and the exertion of a massive influence on Japan, Korea, and possibly even India. Hence the history of China offers the key to the history of all of East Asia. This chapter will tell the story of how China did become Chinese.

这种怪事暗示,中国过去也曾经是形形色色、变化多端的,就像其他所有人口众多的国家现在仍然表现出来的那样。中国的不同之处仅仅在于它在早得多的时候便已统一了。它的“中国化”就是在一个古代的民族大熔炉里使一个广大的地区迅速单一化,重新向热带东南亚移民,并对日本、朝鲜以及可能还有印度发挥重大的影响。因此,中国的历史提供了了解整个东南亚历史的钥匙。本章就是要讲一讲关于中国是怎样成为中国人的中国的这个故事。

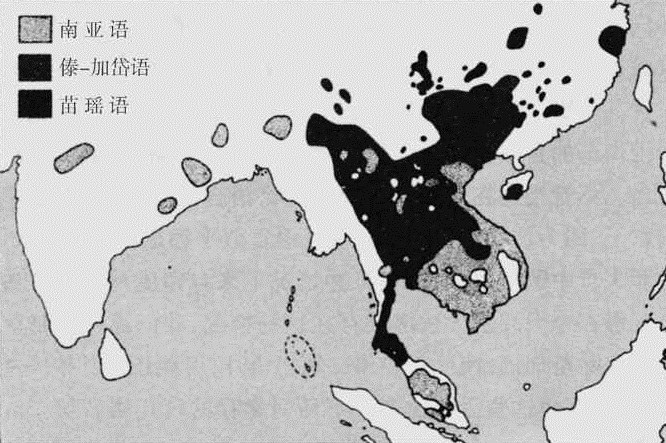

A CONVENIENT STARTING point is a detailed linguistic map of China (see Figure 16.1). A glance at it is an eye-opener to all of us accustomed to thinking of China as monolithic. It turns out that, in addition to China's eight “big” languages—Mandarin and its seven close relatives (often referred to collectively simply as “Chinese”), with between 11 million and 800 million speakers each—China also has over 130 “little” languages, many of them with just a few thousand speakers. All these languages, “big” and “little,” fall into four language families, which differ greatly in the compactness of their distributions.

方便的起始点就是一幅详细的中国语言地图(见图16.1及图16.2)。对我们所有习惯于把中国看作铁板一块的人来说,看一看这幅地图真叫人大开眼界。原来,中国除了8种“大”语言——官话及其7个近亲(常常只是被统称为“中国话”),说这些语言的人从1100万到8亿不等——还有130多个“小”语种,其中许多语种只有几千人使用。所有这些“大”、“小”语种分为4个语族,它们在分布密度上差异很大。

At the one extreme, Mandarin and its relatives, which constitute the Chinese subfamily of the Sino-Tibetan language family, are distributed continuously from North to South China. One could walk through China, from Manchuria in the north to the Gulf of Tonkin in the south, while remaining entirely within land occupied by native speakers of Mandarin and its relatives. The other three families have fragmented distributions, being spoken by “islands” of people surrounded by a “sea” of speakers of Chinese and other language families.

官话及其亲属语言,它们构成了汉藏语系中的汉语族,连续分布在中国的华北和华南。人们可以从中国东北徒步穿行整个中国到达南面的东京湾[1],而仍然没有走出说官话及其亲属语言的人们所居住的土地。其他3个语族的分布零碎分散,为一些“聚居区”的人们所使用,被说汉语和其他亲属语言的人的“汪洋大海”所包围。

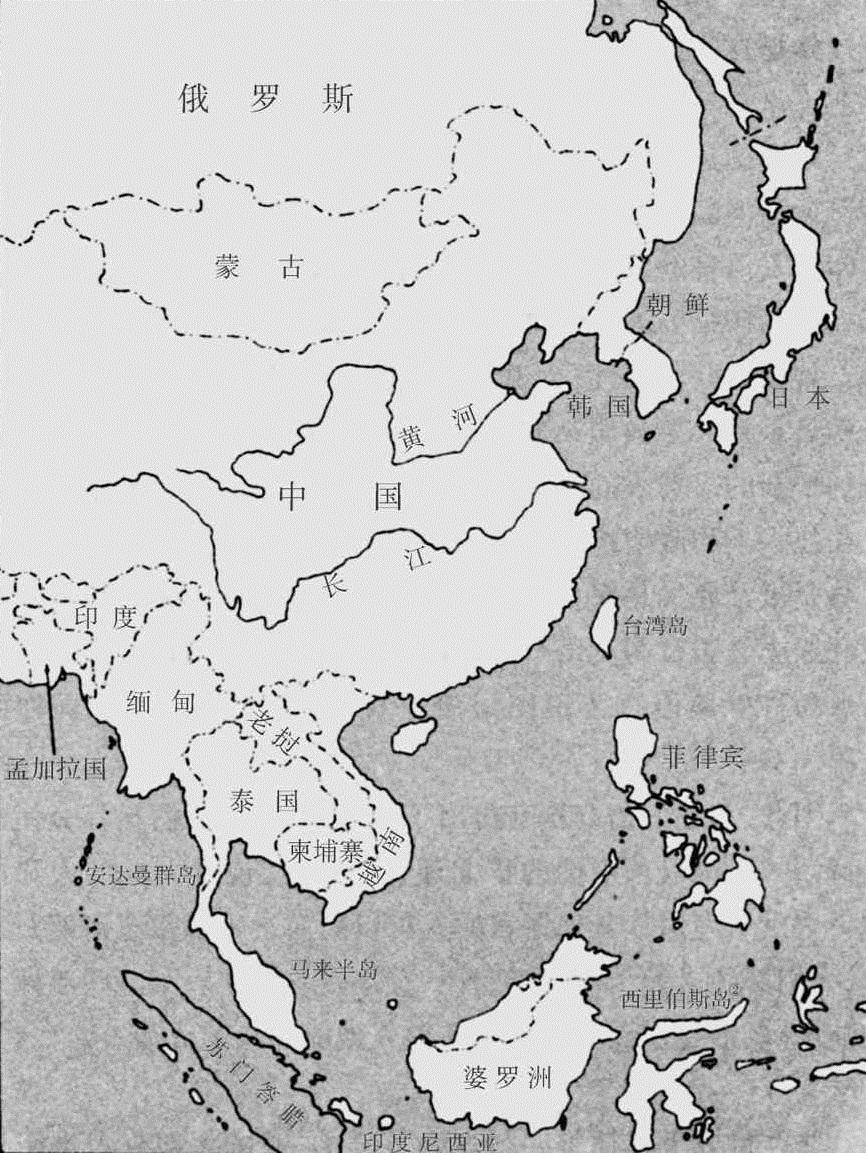

图16.1中国和东南亚的4大语族

图16.2东亚和东南亚的现代政治边界,用以说明图16.1所示语族的分布。

Especially fragmented is the distribution of the Miao-Yao (alias Hmong-Mien) family, which consists of 6 million speakers divided among about five languages, bearing the colorful names of Red Miao, White Miao (alias Striped Miao), Black Miao, Green Miao (alias Blue Miao), and Yao. Miao-Yao speakers live in dozens of small enclaves, all surrounded by speakers of other language families and scattered over an area of half a million square miles, extending from South China to Thailand. More than 100,000 Miao-speaking refugees from Vietnam have carried this language family to the United States, where they are better known under the alternative name of Hmong.

特别分散的是苗瑶(亦称曼-勉)语族的分布,这个语族包括600万人,大约分为5种语言,带有富于色彩的名称:红苗语、白苗语(亦称条纹苗语)、黑苗语、绿苗语(亦称蓝苗语)和瑶语。说苗瑶语的人生活在几十个孤立的小块地区,被其他语族的人所包围,它们散布在一个50万平方英里的地区内,从华南一直延伸到泰国。来自越南的10多万说苗语的难民把这个语支带到了美国,不过他们在美国却是以这个语族的另一名称曼语而更为人所知。

Another fragmented language group is the Austroasiatic family, whose most widely spoken languages are Vietnamese and Cambodian. The 60 million Austroasiatic speakers are scattered from Vietnam in the east to the Malay Peninsula in the south and to northern India in the west. The fourth and last of China's language families is the Tai-Kadai family (including Thai and Lao), whose 50 million speakers are distributed from South China southward into Peninsular Thailand and west to Myanmar (Figure 16.1).

另一个零碎分散的语系是南亚语系,这个语系中使用最广泛的语言是越南语和柬埔寨语。6000万说南亚语的人的分布地区,从东面的越南到南面的马来半岛,再到西面的印度。中国语族中的第4个也是最后一个语支是傣-加岱语支(包括泰语和老挝语),这个语支有5000万人,其分布从华南向南进入泰国半岛,向西到达缅甸。

Naturally, Miao-Yao speakers did not acquire their current fragmented distribution as a result of ancient helicopter flights that dropped them here and there over the Asian landscape. Instead, one might guess that they once had a more nearly continuous distribution, which became fragmented as speakers of other language families expanded or induced Miao-Yao speakers to abandon their tongues. In fact, much of that process of linguistic fragmentation occurred within the past 2,500 years and is well documented historically. The ancestors of modern speakers of Thai, Lao, and Burmese all moved south from South China and adjacent areas to their present locations within historical times, successively inundating the settled descendants of previous migrations. Speakers of Chinese languages were especially vigorous in replacing and linguistically converting other ethnic groups, whom Chinese speakers looked down upon as primitive and inferior. The recorded history of China's Zhou Dynasty, from 1100 to 221 B.C., describes the conquest and absorption of most of China's non-Chinese-speaking population by Chinese-speaking states.

当然,今天说苗瑶语的人的分布之所以如此零碎分散,不是由于古代有什么直升飞机把他们东一处西一处地投掷在亚洲大地上。人们倒是可以猜想他们本来具有一种比较近乎连续的分布,后来之所以变得零碎分散,是由于其他语族的人进行扩张,或诱使说苗瑶语的人放弃自己的语言。事实上,语言分布的这种变得零碎分散的过程,有很大一部分都是在过去的2500年内发生的,作为历史事实这有充分的文献可资证明。现代说泰语、老挝语和缅甸语的人的祖先,都是在历史上从华南和邻近地区迁往现在的地点,相继淹没了早先移民在那里定居的后代。说汉语的族群特别卖力地取代其他族群,并在语言上改变他们,因为说汉语的族群鄙视其他族群,认为他们是原始的劣等族群。从公元前1100年到公元前221年的中国周朝的历史记载,描写了一些说汉语的诸侯国对中国大部分非汉语人口的征服和吸收。

We can use several types of reasoning to try to reconstruct the linguistic map of East Asia as of several thousand years ago. First, we can reverse the historically known linguistic expansions of recent millennia. Second, we can reason that modern areas with just a single language or related language group occupying a large, continuous area testify to a recent geographic expansion of that group, such that not enough historical time has elapsed for it to differentiate into many languages. Finally, we can reason conversely that modern areas with a high diversity of languages within a given language family lie closer to the early center of distribution of that language family.

我们可以利用几种推理尽可能地重新绘制出几千年前的东亚语言地图。首先,我们可以把已知的最近几千年的语言扩张史颠倒过来。其次,我们可以作这样的推理:如果现代的某些地区只有一种语言或有亲属关系的语族,而这一语言或语族又占有一个广大的连续地区,那么这些地区就证明了这一语族在地理上的扩张,只是由于时间还不够长,它还没有来得及分化成许多语言。最后,我们还可以作反向的推理:如果在现代的某些地区内存在着属于某一特定语系的语言高度多样性现象,那么这些地区差不多就是该语系的早期分布中心。

Using those three types of reasoning to turn back the linguistic clock, we conclude that North China was originally occupied by speakers of Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages; that different parts of South China were variously occupied by speakers of Miao-Yao, Austroasiatic, and Tai-Kadai languages; and that Sino-Tibetan speakers have replaced most speakers of those other families over South China. An even more drastic linguistic upheaval must have swept over tropical Southeast Asia to the south of China—in Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Peninsular Malaysia. Whatever languages were originally spoken there must now be entirely extinct, because all of the modern languages of those countries appear to be recent invaders, mainly from South China or, in a few cases, from Indonesia. Since Miao-Yao languages barely survived into the present, we might also guess that South China once harbored still other language families besides Miao-Yao, Austroasiatic, and Tai-Kadai, but that those other families left no modern surviving languages. As we shall see, the Austronesian language family (to which all Philippine and Polynesian languages belong) may have been one of those other families that vanished from the Chinese mainland, and that we know only because it spread to Pacific islands and survived there.

运用这3种推理来拨回语言时钟,我们就能断定:中国的华北原先为说汉语和其他汉藏语的人所占据;华南的不同地区在不同时间里为说苗瑶语、南亚语和傣-加岱语的人所占据;而说汉藏语的人取代了整个华南地区大多数说其他这些语言的人。一种甚至更加引人瞩目的语言剧变想必席卷了从热带东南亚到中国南部的整个地区——泰国、缅甸、老挝、柬埔寨、越南和马来半岛。不管当初在那些地方说过什么语言,现在必定都已全部消亡了,因为这些国家的所有现代语言似乎都是近代的外来语,主要来自中国华南,或者在某些情况下来自印度尼西亚。鉴于苗瑶语在今天几乎无法继续存在这一情况,我们还可以猜测当年华南除苗瑶语、南亚语和傣-加岱语外,可能还有其他一些语族,不过其他这些语族没有留下任何幸存的现代语言罢了。我们还将看到,南岛语系(所有菲律宾和波利尼西亚语言属于这一语系)可能就是从中国大陆消失的其他这些语系之一,而我们之所以知道这一语系,仅仅因为它传播到了太平洋诸岛并在那里存在下来。

These language replacements in East Asia remind us of the spread of European languages, especially English and Spanish, into the New World, formerly home to a thousand or more Native American languages. We know from our recent history that English did not come to replace U.S. Indian languages merely because English sounded musical to Indians' ears. Instead, the replacement entailed English-speaking immigrants' killing most Indians by war, murder, and introduced diseases, and the surviving Indians' being pressured into adopting English, the new majority language. The immediate causes of that language replacement were the advantages in technology and political organization, stemming ultimately from the advantage of an early rise of food production, that invading Europeans held over Native Americans. Essentially the same processes accounted for the replacement of Aboriginal Australian languages by English, and of subequatorial Africa's original Pygmy and Khoisan languages by Bantu languages.

东亚的这种语言更替使我们想起了欧洲语言尤其是英语和西班牙语向新大陆传播的情况。新大陆以前曾是一千种或更多的印第安语言的发源地。我们从我们的近代史得知,英语不是仅仅因为印第安人听起来悦耳才终于取代了美国的印第安语言的。相反,这种更替需要说英语的移民通过战争、屠杀和带来的疾病来杀死大多数印第安人,使幸存的印第安人不得不采用英语这个新的多数人的语言。语言更替的直接原因是外来的欧洲人在技术上和政治组织上所拥有的对印第安人的优势,而这种优势归根结底又是来自很早就出现粮食生产所带来的优势。澳大利亚土著语言为英语所更替以及非洲赤道以南地区原来的俾格米和科伊桑语言为班图语所更替,基本上都经历了同样的过程。

Hence East Asia's linguistic upheavals raise a corresponding question: what enabled Sino-Tibetan speakers to spread from North China to South China, and speakers of Austroasiatic and the other original South China language families to spread south into tropical Southeast Asia? Here, we must turn to archaeology for evidence of the technological, political, and agricultural advantages that some Asians evidently gained over other Asians.

因此,东亚的语言剧变提出了一个相应的问题:是什么使说汉藏语的人得以从中国的华北迁往华南,使说南亚语的人和说原为中国华南语族其他语言的人得以向南进入热带东南亚?这里,我们必须求助于考古学,看一看是否有证据表明某些亚洲人在技术、政治和农业方面获得了对其他亚洲人的优势。

AS EVERYWHERE ELSE in the world, the archaeological record in East Asia for most of human history reveals only the debris of hunter-gatherers using unpolished stone tools and lacking pottery. The first East Asian evidence for something different comes from China, where crop remains, bones of domestic animals, pottery, and polished (Neolithic) stone tools appear by around 7500 B.C. That date is within a thousand years of the beginning of the Neolithic Age and food production in the Fertile Crescent. But because the previous millennium in China is poorly known archaeologically, one cannot decide at present whether the origins of Chinese food production were contemporaneous with those in the Fertile Crescent, slightly earlier, or slightly later. At the least, we can say that China was one of the world's first centers of plant and animal domestication.

与在世界上其他每一个地方一样,东亚的大部分人类历史的考古记录,仅仅显示了使用粗糙石器并且没有陶器的狩猎采集族群的遗迹。在东亚,表明情况有所不同的最早证据来自中国,因为那里出现了公元前7500年左右的作物残迹、家畜的骨头、陶器和打磨的(新石器时代的)石器。这个年代距离新石器时代和新月沃地粮食生产开始的时间不到1000年。但由于在这之前1000年的中国情况在考古上知之甚少,我们目前还无法确定中国粮食生产的开始究竟与新月沃地同时,还是稍早或稍晚。至少,我们可以说,中国是世界上最早的动植物驯化中心之一。

China may actually have encompassed two or more independent centers of origins of food production. I already mentioned the ecological differences between China's cool, dry north and warm, wet south. At a given latitude, there are also ecological distinctions between the coastal lowlands and the interior uplands. Different wild plants are native to these disparate environments and would thus have been variously available to incipient farmers in various parts of China. In fact, the earliest identified crops were two drought-resistant species of millet in North China, but rice in South China, suggesting the possibility of separate northern and southern centers of plant domestication.

中国实际上可能有两个或更多的独立出现粮食生产的中心。我已经提到过中国凉爽、干燥的北方与温暖、潮湿的南方在生态方面的差异。即使在同一纬度,沿海低地与内陆高原之间也存在着生态差异。不同的野生植物生长在这些根本不同的环境里,因此中国不同地区的早期农民对这些植物可能会有不同的利用。事实上,已经验明的最早作物是华北的两种耐旱的黍子,而华南的水稻则表明可能存在南北两个不同的植物驯化中心。

Chinese sites with the earliest evidence of crops also contained bones of domestic pigs, dogs, and chickens. These domestic animals and crops were gradually joined by China's many other domesticates. Among the animals, water buffalo were most important (for pulling plows), while silkworms, ducks, and geese were others. Familiar later Chinese crops include soybeans, hemp, citrus fruit, tea, apricots, peaches, and pears. In addition, just as Eurasia's east-west axis permitted many of these Chinese animals and crops to spread westward in ancient times, West Asian domesticates also spread eastward to China and became important there. Especially significant western contributions to ancient China's economy have been wheat and barley, cows and horses, and (to a lesser extent) sheep and goats.

中国的一些考古遗址不但有最早的作物证据,而且还有驯养的猪、狗和鸡的骨头。除了这些驯养的动物和作物,渐渐又有了中国的其他许多驯化动植物。在这些动物中,水牛是最重要的(用于拉犁),而蚕、鸭和鹅则是另一些最重要的动物。后来的一些为人们所熟悉的作物包括大豆、大麻、柑橘果、茶叶、杏、桃和梨。此外,正如欧亚大陆的东西轴向使许多这样的中国动物和作物在古代向西传播一样,西亚的驯化动植物也向东传播到中国,并在那里取得重要的地位。西亚对古代中国经济特别重大的贡献是小麦和大麦、牛和马以及(在较小的程度上)绵羊和山羊。

As elsewhere in the world, in China food production gradually led to the other hallmarks of “civilization” discussed in Chapters 11–14. A superb Chinese tradition of bronze metallurgy had its origins in the third millennium B.C. and eventually resulted in China's developing by far the earliest cast-iron production in the world, around 500 B.C. The following 1,500 years saw the outpouring of Chinese technological inventions, mentioned in Chapter 13, that included paper, the compass, the wheelbarrow, and gunpowder. Fortified towns emerged in the third millennium B.C., with cemeteries whose great variation between unadorned and luxuriously furnished graves bespeaks emerging class differences. Stratified societies whose rulers could mobilize large labor forces of commoners are also attested by huge urban defensive walls, big palaces, and eventually the Grand Canal (the world's longest canal, over 1,000 miles long), linking North and South China. Writing is preserved from the second millennium B.C. but probably arose earlier. Our archaeological knowledge of China's emerging cities and states then becomes supplemented by written accounts of China's first dynasties, going back to the Xia Dynasty, which arose around 2000 B.C.

和在世界上的其他地方一样,粮食生产在中国逐步产生了其他一些在第十一到第十四章所讨论的“文明”标志。中国非凡的青铜冶炼传统开始于公元前3000年至2000年间,最后在公元前500年左右导致在中国发展出世界上最早的铸铁生产。其后的1500年则是第十三章提到的中国技术发明的大量涌现时期,这些发明包括纸、罗盘、独轮车和火药。筑有防御工事的城市在公元前第三个一千年间出现了,墓葬形制出现了很大变化,有的朴素无华,有的陈设奢侈,这表明出现了阶级差别。保卫城市的高大城墙、巨大的宫殿、最后还有沟通中国南北的大运河(世界上最长的运河,全长1000多英里),证明等级社会已经出现,因为只有这样的社会的统治者才能把大量的平民劳动力动员起来。现在保存下来的文字是在公元前第二个一千年间出现的,但也可能出现得更早。我们关于中国出现了城市和国家的考古知识,后来又得到了关于中国最早的几个王朝的文字记载的补充,这些王朝可以追溯到公元前2000年左右兴起的夏朝。

As for food production's more sinister by-product of infectious diseases, we cannot specify where within the Old World most major diseases of Old World origin arose. However, European writings from Roman and medieval times clearly describe the arrival of bubonic plague and possibly smallpox from the east, so these germs could be of Chinese or East Asian origin. Influenza (derived from pigs) is even more likely to have arisen in China, since pigs were domesticated so early and became so important there.

至于粮食生产的更具灾难性的副产品传染病,我们还不能确定源于旧大陆的一些最主要的疾病发生在旧大陆的什么地方。然而,从罗马时代到中世纪的一些欧洲著作清楚地记述了腺鼠疫、可能还有天花来自东方,因此这些病菌可能源自中国或东亚。流行性感冒(起源于猪)甚至更可能发生在中国,因为猪很早就在中国驯养了,并且成了中国十分重要的家畜。

China's size and ecological diversity spawned many separate local cultures, distinguishable archaeologically by their differing styles of pottery and artifacts. In the fourth millennium B.C. those local cultures expanded geographically and began to interact, compete with each other, and coalesce. Just as exchanges of domesticates between ecologically diverse regions enriched Chinese food production, exchanges between culturally diverse regions enriched Chinese culture and technology, and fierce competition between warring chiefdoms drove the formation of ever larger and more centralized states (Chapter 14).

中国广大的幅员和生态的多样性造就了许多不同的地区性文化,从考古上来看,根据它们的陶器和人工制品的不同风格,这一点是可以区别出来的。在公元前第四个一千年期间,这些地区性文化在地理上扩张了,它们开始相互作用,相互竞争,相互融合。正如生态多样性地区之间驯化动植物的交流丰富了中国的粮食生产一样,文化多样性地区之间的交流丰富了中国的文化和技术,而交战的酋长管辖地之间的激烈竞争推动了规模更大、权力更集中的国家的形成(第十四章)。

While China's north-south gradient retarded crop diffusion, the gradient was less of a barrier there than in the Americas or Africa, because China's north-south distances were smaller; and because China's is transected neither by desert, as is Africa and northern Mexico, nor by a narrow isthmus, as is Central America. Instead, China's long east-west rivers (the Yellow River in the north, the Yangtze River in the south) facilitated diffusion of crops and technology between the coast and inland, while its broad east-west expanse and relatively gentle terrain, which eventually permitted those two river systems to be joined by canals, facilitated north-south exchanges. All these geographic factors contributed to the early cultural and political unification of China, whereas western Europe, with a similar area but a more rugged terrain and no such unifying rivers, has resisted cultural and political unification to this day.

虽然中国的南北梯度妨碍了作物的传播,但这种梯度在中国不像在美洲或非洲那样成为一种障碍,因为中国的南北距离较短;同时也因为中国的南北之间既不像非洲和墨西哥北部那样被沙漠阻断,也不像中美洲那样被狭窄的地峡隔开。倒是中国由西向东的大河(北方的黄河、南方的长江)方便了沿海地区与内陆之间作物和技术的传播,而中国东西部之间的广阔地带和相对平缓的地形最终使这两条大河的水系得以用运河连接起来,从而促进了南北之间的交流。所有这些地理因素促成了中国早期的文化和政治统一,而西方的欧洲虽然面积和中国差不多,但地势比较高低不平,也没有这样连成一体的江河,所以欧洲直到今天都未能实现文化和政治的统一。

Some developments spread from south to north in China, especially iron smelting and rice cultivation. But the predominant direction of spread was from north to south. That trend is clearest for writing: in contrast to western Eurasia, which produced a plethora of early writing systems, such as Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphics, Hittite, Minoan, and the Semitic alphabet, China developed just a single well-attested writing system. It was perfected in North China, spread and preempted or replaced any other nascent system, and evolved into the writing still used in China today. Other major features of North Chinese societies that spread southward were bronze technology, Sino-Tibetan languages, and state formation. All three of China's first three dynasties, the Xia and Shang and Zhou Dynasties, arose in North China in the second millennium B.C.

在中国,有些新事物是由南向北传播的,尤其是铁的冶炼和水稻的栽培。但主要的传播方向是由北而南。这个趋向在文字上表现得最为明显:欧亚大陆西部曾产生过太多的书写系统,如苏美尔的楔形文字、埃及的象形文字、赫梯文字[3]、弥诺斯文字和闪语字母。中国则不同,它只产生了一种得到充分证明的书写系统。它在华北得到完善,并流传各地,预先制止了任何其他不成熟的书写系统的发展或取而代之,最后演化为今天仍在中国使用的文字。华北社会向南传播的其他一些重要的有特色的东西是青铜工艺、汉藏语言和国家的组成。中国的3个最早的王朝——夏、商、周都是在公元前第二个一千年间在华北兴起的。

Preserved writings of the first millennium B.C. show that ethnic Chinese already tended then (as many still do today) to feel culturally superior to non-Chinese “barbarians,” while North Chinese tended to regard even South Chinese as barbarians. For example, a late Zhou Dynasty writer of the first millennium B.C. described China's other peoples as follows: “The people of those five regions—the Middle states and the Rong, Yi, and other wild tribes around them—had all their several natures, which they could not be made to alter. The tribes on the east were called Yi. They had their hair unbound, and tattooed their bodies. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked by fire.” The Zhou author went on to describe wild tribes to the south, west, and north as indulging in equally barbaric practices, such as turning their feet inward, tattooing their foreheads, wearing skins, living in caves, not eating cereals, and, of course, eating their food raw.

现存的公元前第一个一千年中的著作表明,当时的华夏族就已常常(就像今天许多人仍然在做的那样)觉得在文化上比非华夏族的“野蛮人”优越,而华北人也常常甚至把华南人也看作野蛮人。例如,公元前第一个一千年中周朝后期的一位作家对中国的其他民族作如下的描绘:“中国戎夷,五方之民,皆有性也,不可推移。东方曰夷,被发文身,有不火食者矣。”这位周朝的作者接着又把南方、西方和北方的原始部落说成是沉溺于同样野蛮的习俗:“南方曰蛮,雕题交趾,有不火食者矣。西方曰戎,被发衣皮,有不粒食者矣。北方曰狄,衣羽毛穴居,有不粒食者矣。”[4]

States organized by or modeled on that Zhou Dynasty of North China spread to South China during the first millennium B.C., culminating in China's political unification under the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C. Its cultural unification accelerated during that same period, as literate “civilized” Chinese states absorbed, or were copied by, the illiterate “barbarians.” Some of that cultural unification was ferocious: for instance, the first Qin emperor condemned all previously written historical books as worthless and ordered them burned, much to the detriment of our understanding of early Chinese history and writing. Those and other draconian measures must have contributed to the spread of North China's Sino-Tibetan languages over most of China, and to reducing the Miao-Yao and other language families to their present fragmented distributions.

由华北的这个周王朝建立的或以周王朝为榜样的一些国家,在公元前第一个一千年中向华南扩展,最后于公元前221年实现了秦王朝统治下的中国的政治统一。中国的文化统一也在同一期间加速进行,有文字的、“文明的”华夏诸国吸收并同化了没有文字的“野蛮人”,或成为这些人仿效的榜样。这种文化的统一有时是很残暴的,例如秦始皇宣布以前的所有典籍都是没有价值的,并下令把它们焚毁,这给我们现在了解中国的早期历史和文字造成了很大的不便。这些和其他一些严厉的措施对于华北的汉藏语向中国大部分地区传播,并使苗瑶语和其他语族的分布落到如今零碎分散的状况,必定起到过推动的作用。

Within East Asia, China's head start in food production, technology, writing, and state formation had the consequence that Chinese innovations also contributed heavily to developments in neighboring regions. For instance, until the fourth millennium B.C. most of tropical Southeast Asia was still occupied by hunter-gatherers making pebble and flake stone tools belonging to what is termed the Hoabinhian tradition, named after the site of Hoa Binh, in Vietnam. Thereafter, Chinese-derived crops, Neolithic technology, village living, and pottery similar to that of South China spread into tropical Southeast Asia, probably accompanied by South China's language families. The historical southward expansions of Burmese, Laotians, and Thais from South China completed the Sinification of tropical Southeast Asia. All those modern peoples are recent offshoots of their South Chinese cousins.

在东亚,中国在粮食生产、技术、文字和国家组成方面的领先优势所产生的结果是,中国的创新改革对邻近地区的发展也作出了重大的贡献。例如,直到公元前第四个一千年,热带东南亚仍然为狩猎采集族群所占据,这些人制造了属于以越南和平遗址命名的所谓和平文化[5]传统的砾石工具和石片工具。从那以后,源自中国的作物、新石器时代的技术、村居生活以及与华南陶器相似的陶器传入了热带东南亚,也许一起来到的还有华南的一些语族。历史上缅甸人、老挝人和泰人的向南扩张使热带东南亚的中国化宣告完成。所有这些现代民族都是他们的华南同胞的近代旁系亲属。

So overwhelming was this Chinese steamroller that the former peoples of tropical Southeast Asia have left behind few traces in the region's modern populations. Just three relict groups of hunter-gatherers—the Semang Negritos of the Malay Peninsula, the Andaman Islanders, and the Veddoid Negritos of Sri Lanka—remain to suggest that tropical Southeast Asia's former inhabitants may have been dark-skinned and curly-haired, like modern New Guineans and unlike the light-skinned, straight-haired South Chinese and the modern tropical Southeast Asians who are their offshoots. Those relict Negritos of Southeast Asia may be the last survivors of the source population from which New Guinea was colonized. The Semang Negritos persisted as hunter-gatherers trading with neighboring farmers but adopted an Austroasiatic language from those farmers—much as, we shall see, Philippine Negrito and African Pygmy hunter-gatherers adopted languages from their farmer trading partners. Only on the remote Andaman Islands do languages unrelated to the South Chinese language families persist—the last linguistic survivors of what must have been hundreds of now extinct aboriginal Southeast Asian languages.

中国的这种影响就像蒸汽压路机一样势不可挡,先前的热带东南亚民族在这一地区的现代居民中几乎没有留下任何痕迹。只剩下狩猎采集族群的3个孑遗群体——马来半岛的塞芒族矮小黑人、安达曼群岛岛民和斯里兰卡维多依族矮小黑人——使我们想到热带东南亚的原先居民可能是黑肤、鬈发,就像现代的新几内亚人,而不像肤色较浅、直发的中国华南人及其旁系亲属现代的热带东南亚人。东南亚的这些孑遗的矮小黑人可能就是当初开拓新几内亚的原住民的最后幸存者。塞芒族矮小黑人仍然过着狩猎采集生活,他们和附近的农民进行物物交换,但也从这些农民那里采用了一种南亚语言——就像我们将要看到的那样,菲律宾矮小黑人和非洲俾格米狩猎采集族群也是采用了他们的农民交易伙伴的语言。只有在遥远的安达曼群岛上,一些与华南语族没有亲属关系的语言继续保存了下来——它们是为数必定多达几百种的现已灭绝的东南亚土著语言中最后幸存下来的语言。

Even Korea and Japan were heavily influenced by China, although their geographic isolation from it ensured that they did not lose their languages or physical and genetic distinctness, as did tropical Southeast Asia. Korea and Japan adopted rice from China in the second millennium B.C., bronze metallurgy by the first millennium B.C., and writing in the first millennium A.D. China also transmitted West Asian wheat and barley to Korea and Japan.

甚至朝鲜和日本也受到了中国的巨大影响,不过它们在地理上与中国相隔绝的状态,保证了它们没有像热带东南亚那样失去自己的语言以及体质和遗传特征。朝鲜和日本在公元前第二个一千年中采纳了中国的水稻,在公元前第一个一千年中采用了中国的青铜冶炼术,在公元第一个一千年中采用了中国的文字。中国还把西亚的小麦和大麦传入朝鲜和日本。

In thus describing China's seminal role in East Asian civilization, we should not exaggerate. It is not the case that all cultural advances in East Asia stemmed from China and that Koreans, Japanese, and tropical Southeast Asians were noninventive barbarians who contributed nothing. The ancient Japanese developed some of the oldest pottery in the world and settled as hunter-gatherers in villages subsisting on Japan's rich seafood resources, long before the arrival of food production. Some crops were probably domesticated first or independently in Japan, Korea, and tropical Southeast Asia.

我们在这样介绍中国在东亚文明中所起的重要作用时切不可言过其实。事实上,东亚的文化进步并不全部源于中国,朝鲜人、日本人和热带东南亚人也不是毫无贡献的没有创造能力的野蛮人。古代的日本人发明了世界上一些最古老的陶器制造技术,并在粮食生产传入之前很久作为狩猎采集族群就已在村庄里定居,靠日本丰富的海产资源维持生计。有些作物可能是在日本、朝鲜和热带东南亚最早或独立驯化出来的。

But China's role was nonetheless disproportionate. For example, the prestige value of Chinese culture is still so great in Japan and Korea that Japan has no thought of discarding its Chinese-derived writing system despite its drawbacks for representing Japanese speech, while Korea is only now replacing its clumsy Chinese-derived writing with its wonderful indigenous han'g l alphabet. That persistence of Chinese writing in Japan and Korea is a vivid 20th-century legacy of plant and animal domestication in China nearly 10,000 years ago. Thanks to the achievements of East Asia's first farmers, China became Chinese, and peoples from Thailand to (as we shall see in the next chapter) Easter Island became their cousins.

但是,中国的作用仍然是太大了。例如,中国文化的声望值在日本和朝鲜仍然很高,虽然日语中源自中国的书写系统在表达日本语言方面存在着种种缺点,但日本并不打算抛弃它,而朝鲜也只是在不久前才用本国的奇妙的谚文字母取代了笨拙的源自中国的文字。中国文字在日本和朝鲜的持续存在是将近1万年前动植物在中国驯化的20世纪的生动遗产。由于东亚最早的农民所取得的成就,中国成了中国人的中国,而从泰国来到(我们将在下一章看到)复活节岛的民族就成了他们的远亲。

注释:

1 东京湾:某些外国人沿用的殖民主义者对在中国和越南之间的北部湾的称呼。——译者

2 西里伯斯岛:印度尼西亚中部苏拉威西岛的旧称。——译者

3 赫梯文字:赫梯为公元前17世纪左右在小亚细亚及叙利亚建立的强大古国,后为亚述人征服。赫梯语据信属印欧语系,其文字为楔形文字与象形文字并存。——译者

4 以上引文见中国《礼记·王制》。——译者

5 和平文化:指首先在越南和平省发现的东南亚这一地区的中石器或新石器时代的文化。——译者