CHAPTER 18

第十八章

HEMISPHERES COLLIDING

两个半球的碰撞

THE LARGEST POPULATION REPLACEMENT OF THE LAST 13,000 years has been the one resulting from the recent collision between Old World and New World societies. Its most dramatic and decisive moment, as we saw in Chapter 3, occurred when Pizarro's tiny army of Spaniards captured the Inca emperor Atahuallpa, absolute ruler of the largest, richest, most populous, and administratively and technologically most advanced Native American state. Atahuallpa's capture symbolizes the European conquest of the Americas, because the same mix of proximate factors that caused it was also responsible for European conquests of other Native American societies. Let us now return to that collision of hemispheres, applying what we have learned since Chapter 3. The basic question to be answered is: why did Europeans reach and conquer the lands of Native Americans, instead of vice versa? Our starting point will be a comparison of Eurasian and Native American societies as of A.D. 1492, the year of Columbus's “discovery” of the Americas.

过去13000年中最大的人口更替是新、旧大陆社会之间新近的碰撞引起的。我们在第三章看到,这种碰撞的最富戏剧性也最具决定性的时刻,是皮萨罗的小小西班牙军队俘虏了印加帝国皇帝阿塔瓦尔帕。阿塔瓦尔帕是最大、最富有、人口最多、管理和技术最先进的印第安国家的独裁统治者,他的被俘成了欧洲人征服美洲的象征,因为造成这一事件的一成不变的各种近似因素,也是欧洲人征服其他印第安社会的部分原因。现在,让我们回到两个半球的那次碰撞上来,把我们自第三章以来所学到的知识加以运用。需要回答的根本问题是:为什么是欧洲人到达了印第安人的国家并征服了它,而不是相反?我们讨论的起始点就是把欧亚大陆社会和印第安社会作一比较,时间是到公元1492年即哥伦布“发现”美洲的那一年为止。

OUR COMPARISON BEGINS with food production, a major determinant of local population size and societal complexity—hence an ultimate factor behind the conquest. The most glaring difference between American and Eurasian food production involved big domestic mammal species. In Chapter 9 we encountered Eurasia's 13 species, which became its chief source of animal protein (meat and milk), wool, and hides, its main mode of land transport of people and goods, its indispensable vehicles of warfare, and (by drawing plows and providing manure) a big enhancer of crop production. Until waterwheels and windmills began to replace Eurasia's mammals in medieval times, they were also the major source of its “industrial” power beyond human muscle power—for example, for turning grindstones and operating water lifts. In contrast, the Americas had only one species of big domestic mammal, the llama / alpaca, confined to a small area of the Andes and the adjacent Peruvian coast. While it was used for meat, wool, hides, and goods transport, it never yielded milk for human consumption, never bore a rider, never pulled a cart or a plow, and never served as a power source or vehicle of warfare.

我们的比较从粮食生产开始。粮食生产是当地人口多寡和社会复杂程度的一个重要的决定因素——因此也是实现征服的终极因素。美洲的粮食生产与欧亚大陆的粮食生产的最引人注目的差异涉及驯养的大型哺乳动物的种类。在第九章我们接触到欧亚大陆的13种大型哺乳动物,它们成了欧亚大陆的动物蛋白(肉和奶)、毛绒和皮革的主要来源,是对人员和货物陆地运输的主要工具,是战争中不可或缺的手段,也是(通过拉犁和提供粪肥)作物增产的保证。在水轮与风车于中世纪开始取代欧亚大陆的哺乳动物之前,它们还是人的膂力之外的重要的“工业”动力——例如,用来转动石磨和提升汲水器具。相形之下,美洲只有一种驯养的大型哺乳动物——美洲驼/羊驼,而这种动物也只有安第斯山脉的一个很小地区和邻近的秘鲁沿海地区才有。虽然人们利用它是为了肉、毛绒、皮革和货物运输,但它从不产奶供人消费,从不供人骑乘,从不拉车或拉犁,也从不被用作一种动力源或战争工具。

That's an enormous set of differences between Eurasian and Native American societies—due largely to the Late Pleistocene extinction (extermination?) of most of North and South America's former big wild mammal species. If it had not been for those extinctions, modern history might have taken a different course. When Cortés and his bedraggled adventurers landed on the Mexican coast in 1519, they might have been driven into the sea by thousands of Aztec cavalry mounted on domesticated native American horses. Instead of the Aztecs' dying of smallpox, the Spaniards might have been wiped out by American germs transmitted by disease-resistant Aztecs. American civilizations resting on animal power might have been sending their own conquistadores to ravage Europe. But those hypothetical outcomes were foreclosed by mammal extinctions thousands of years earlier.

这就是欧亚大陆社会与印第安社会之间巨大的一组差异之所在——这种差异主要是由于更新世晚期北美洲和南美洲原有的大型野生哺乳动物大多数灭绝(被消灭?)所致。如果不是由于这些动物灭绝了,现代史的进程可能会有所不同。当科尔特斯率领他的满身泥汙的雇佣军于1519年在墨西哥海岸登陆时,他们可能会被几千个骑着本地驯化的美洲马的阿兹特克骑兵赶进大海。不是阿兹特克人死于天花,而是那些西班牙人可能会被对疾病有抵抗力的阿兹特克人所传染的美洲病菌消灭光。依靠畜力的美洲文明国家可能会派遣自己的征服者去蹂躏欧洲。但这些假设的结果由于几千年前哺乳动物的灭绝而被排除了。

Those extinctions left Eurasia with many more wild candidates for domestication than the Americas offered. Most candidates disqualify themselves as potential domesticates for any of half a dozen reasons. Hence Eurasia ended up with its 13 species of big domestic mammals and the Americas with just its one very local species. Both hemispheres also had domesticated species of birds and small mammals—the turkey, guinea pig, and Muscovy duck very locally and the dog more widely in the Americas; chickens, geese, ducks, cats, dogs, rabbits, honeybees, silkworms, and some others in Eurasia. But the significance of all those species of small domestic animals was trivial compared with that of the big ones.

这些动物的灭绝使欧亚大陆有了比美洲所提供的多得多的供驯化之用的野生动物。大多数可供驯化的野生动物由于6、7种原因中的任何一种原因而失去了作为可供驯化的动物的潜在资格。因此,欧亚大陆最后只有13种驯养的大型哺乳动物,而美洲只有本地的一种。这两个半球还有驯化的鸟类和小型哺乳动物——在美洲有火鸡、豚鼠和完全属于本地的美洲家鸭以及比较普遍的狗;在欧亚大陆有鸡、鹅、鸭、猫、狗、兔、蜜蜂、蚕和其他一些动物。但所有这些小型的驯养动物的作用比起大型的驯养动物来是微不足道的。

Eurasia and the Americas also differed with respect to plant food production, though the disparity here was less marked than for animal food production. In 1492 agriculture was widespread in Eurasia. Among the few Eurasian hunter-gatherers lacking both crops and domestic animals were the Ainu of northern Japan, Siberian societies without reindeer, and small hunter-gatherer groups scattered through the forests of India and tropical Southeast Asia and trading with neighboring farmers. Some other Eurasian societies, notably the Central Asian pastoralists and the reindeer-herding Lapps and Samoyeds of the Arctic, had domestic animals but little or no agriculture. Virtually all other Eurasian societies engaged in agriculture as well as in herding animals.

欧亚大陆和美洲大陆在植物性粮食生产方面也存在着差异,不过这方面的差异没有动物性粮食生产方面的差异那样明显罢了。1492年,农业已在欧亚大陆普及。在欧亚大陆的少数几个既没有作物也没有家畜的狩猎采集族群中,有日本北部的阿伊努人,没有驯鹿的西伯利亚社会,以及散居印度和热带东南亚雨林、与附近农民进行交换的狩猎采集族群的一些小的群体。其他一些欧亚大陆社会,主要地有中亚的牧人、放牧驯鹿的拉普人和北极地区的萨莫耶德人,他们都饲养家畜,但很少有农业,或完全没有农业。几乎所有其他欧亚大陆社会不但放牧牲口,而且也从事农业。

Agriculture was also widespread in the Americas, but hunter-gatherers occupied a larger fraction of the Americas' area than of Eurasia's. Those regions of the Americas without food production included all of northern North America and southern South America, the Canadian Great Plains, and all of western North America except for small areas of the U.S. Southwest that supported irrigation agriculture. It is striking that the areas of Native America without food production included what today, after Europeans' arrival, are some of the most productive farmlands and pastures of both North and South America: the Pacific states of the United States, Canada's wheat belt, the pampas of Argentina, and the Mediterranean zone of Chile. The former absence of food production in these lands was due entirely to their local paucity of domesticable wild animals and plants, and to geographic and ecological barriers that prevented the crops and the few domestic animal species of other parts of the Americas from arriving. Those lands became productive not only for European settlers but also, in some cases, for Native Americans, as soon as Europeans introduced suitable domestic animals and crops. For instance, Native American societies became renowned for their mastery of horses, and in some cases of cattle and sheepherding, in parts of the Great Plains, the western United States, and the Argentine pampas. Those mounted plains warriors and Navajo sheepherders and weavers now figure prominently in white Americans' image of American Indians, but the basis for that image was created only after 1492. These examples demonstrate that the sole missing ingredients required to sustain food production in large areas of the Americas were domestic animals and crops themselves.

农业在美洲也很普及,但狩猎采集族群在美洲占有的地区比在欧亚大陆大。美洲的这些没有粮食生产的地区包括北美洲的整个北部和南美洲南部、加拿大大平原和北美洲的整个西部,只有美国西南的一些小块地区有灌溉农业。引人注目的是,那些没有粮食生产的印第安地区,包括欧洲人来到后开发的今天北美洲和南美洲的一些最肥沃的农田和草原:美国的沿太平洋各州、加拿大的小麦产区、阿根廷的无树大草原和智利的地中海型气候带。这些地方以前之所以没有粮食生产,完全是由于当地缺少可以驯化的动植物,同时也由于地理和生态障碍使美洲其他地方的作物和几种家畜无法引进。在欧洲移民引进了合适的家畜和作物后,这些地区立即变得富饶起来,这不仅要归功于欧洲移民,而且有时候也要归功于印第安人。例如,在大平原的一些地方,在美国西部和阿根廷无树大草原,印第安社会以驯马和精于放牧牛羊而著称。平原上的骑马战士、纳瓦霍族的牧羊人和编织工,在美洲白人对美洲印第安人的印象中现在占有突出的地位,但这种印象的基础是在1492年以后建立的。这些例子表明,在美洲广大地区唯一缺少的为进行粮食生产所需要的成分是家畜和作物本身。

In those parts of the Americas that did support Native American agriculture, it was constrained by five major disadvantages vis-à-vis Eurasian agriculture: widespread dependence on protein-poor corn, instead of Eurasia's diverse and protein-rich cereals; hand planting of individual seeds, instead of broadcast sowing; tilling by hand instead of plowing by animals, which enables one person to cultivate a much larger area, and which also permits cultivation of some fertile but tough soils and sods that are difficult to till by hand (such as those of the North American Great Plains); lack of animal manuring to increase soil fertility; and just human muscle power, instead of animal power, for agricultural tasks such as threshing, grinding, and irrigation. These differences suggest that Eurasian agriculture as of 1492 may have yielded on the average more calories and protein per person-hour of labor than Native American agriculture did.

在美洲的这些地方,虽然也有了印第安人的农业,但和欧亚大陆的农业相比,它受到五大不利条件的限制:广泛依赖蛋白质含量低的玉米,而不是欧亚大陆的品种繁多、蛋白质丰富的谷物;种子用手一颗颗地点种,而不是撒播;犁地用手而不是用畜力,用畜力犁地使一个人能够耕种大得多的面积,并可耕种某些难以用手耕种的肥沃而坚硬的土壤和长满草根的土地(就像北美大平原的那些土地);缺乏可以增加土壤肥力的动物粪肥;只用人力而不是用畜力来做诸如脱粒、碾磨和灌溉之类的农活。这些差异表明,到1492年为止的欧亚大陆农业平均每个劳动力每小时产生的卡路里和蛋白质要多于印第安的农业。

SUCH DIFFERENCES IN food production constituted a major ultimate cause of the disparities between Eurasian and Native American societies. Among the resulting proximate factors behind the conquest, the most important included differences in germs, technology, political organization, and writing. Of these, the one linked most directly to the differences in food production was germs. The infectious diseases that regularly visited crowded Eurasian societies, and to which many Eurasians consequently developed immune or genetic resistance, included all of history's most lethal killers: smallpox, measles, influenza, plague, tuberculosis, typhus, cholera, malaria, and others. Against that grim list, the sole crowd infectious diseases that can be attributed with certainty to pre-Columbian Native American societies were nonsyphilitic treponemas. (As I explained in Chapter 11, it remains uncertain whether syphilis arose in Eurasia or in the Americas, and the claim that human tuberculosis was present in the Americas before Columbus is in my opinion unproven.)

粮食生产方面的这些差异,构成了欧亚大陆社会与印第安社会之间差异的一个重要的终极原因。在由此而产生的实现征服的近似因素中,最重要的因素包括病菌、技术、政治组织和文字方面的差异。其中与粮食生产方面的差异关系最直接的差异是病菌。有些传染病经常光顾人口拥挤的欧亚大陆社会,许多欧亚大陆人因而逐步形成了免疫力或遗传抵抗力。这些传染病包括历史上所有最致命的疾病:天花、麻疹、流行性感冒、瘟疫、肺结核、斑疹伤寒、霍乱、疟疾和其他疾病。对照这个令人望而生畏的疾病名单,唯一可以有把握归之于哥伦布以前印第安人社会的群众传染病是非梅毒密螺旋体病。(我在第十一章说过,梅毒究竟起源于欧亚大陆还是起源于美洲仍然未能确定,至于在哥伦布以前美洲就已有了人类肺结核病这种说法,是我的尚未得到证明的看法。)

This continental difference in harmful germs resulted paradoxically from the difference in useful livestock. Most of the microbes responsible for the infectious diseases of crowded human societies evolved from very similar ancestral microbes causing infectious diseases of the domestic animals with which food producers began coming into daily close contact around 10,000 years ago. Eurasia harbored many domestic animal species and hence developed many such microbes, while the Americas had very few of each. Other reasons why Native American societies evolved so few lethal microbes were that villages, which provide ideal breeding grounds for epidemic diseases, arose thousands of years later in the Americas than in Eurasia; and that the three regions of the New World supporting urban societies (the Andes, Mesoamerica, and the U.S. Southeast) were never connected by fast, high-volume trade on the scale that brought plague, influenza, and possibly smallpox to Europe from Asia. As a result, even malaria and yellow fever, the infectious diseases that eventually became major obstacles to European colonization of the American tropics, and that posed the biggest barrier to the construction of the Panama Canal, are not American diseases at all but are caused by microbes of Old World tropical origin, introduced to the Americas by Europeans.

说也奇怪,大陆之间在有害的病菌方面的这种差异竟是来自有用的牲畜方面的差异。在拥挤的人类社会引起传染病的大多数病菌,是从引起家畜传染病的那些十分相似的祖代病菌演化而来的,而在大约1万年前,粮食生产者就已开始每天同这些家畜进行密切的接触了。欧亚大陆饲养了许多种家畜,因而也就培养了许多种这样的病菌,而美洲无论是家畜还是病菌都很少。印第安社会演化出来的致命病菌如此之少的另一些原因是:为传染病提供理想的滋生地的村庄在美洲出现的时间要比在欧亚大陆晚几千年;新大陆出现城市社会的3个地区(安第斯山脉地区、中美洲和美国东南部)从来没有同把瘟疫、流行性感冒、可能还有天花从亚洲带到欧洲的那种规模的快速而大量的贸易发生过关系。因此,甚至连疟疾和黄热病也根本不是美洲的疾病,而是由起源于旧大陆热带地区、被欧洲人传入美洲的病菌引起的。而这些传染病最后成为欧洲人向美洲热带地区移民的主要障碍,并成为修建巴拿马运河的最大障碍。

Rivaling germs as proximate factors behind Europe's conquest of the Americas were the differences in all aspects of technology. These differences stemmed ultimately from Eurasia's much longer history of densely populated, economically specialized, politically centralized, interacting and competing societies dependent on food production. Five areas of technology may be singled out:

在帮助欧洲征服美洲的一些直接因素中,可与病菌相提并论的是技术的各方面的差距。这些差距归根到底是由于欧亚大陆有历史悠久得多的依靠粮食生产的人口稠密、经济专业化、政治集中统一、相互作用、相互竞争的社会。有5个技术领域可以挑出来讨论:

First, metals—initially copper, then bronze, and finally iron—were used for tools in all complex Eurasian societies as of 1492. In contrast, although copper, silver, gold, and alloys were used for ornaments in the Andes and some other parts of the Americas, stone and wood and bone were still the principal materials for tools in all Native American societies, which made only limited local use of copper tools.

第一、金属——开始时是铜,后来是青铜,最后是铁——到1492年止已在所有复杂的欧亚大陆社会被用作工具。相比之下,虽然铜、银、金和一些合金已在安第斯山脉地区和美洲的其他一些地方被用作饰物,但石头、木头和骨头在所有印第安社会中仍然是制作工具的主要材料,这些社会只在局部地区有限地利用铜器。

Second, military technology was far more potent in Eurasia than in the Americas. European weapons were steel swords, lances, and daggers, supplemented by small firearms and artillery, while body armor and helmets were also made of solid steel or else of chain mail. In place of steel, Native Americans used clubs and axes of stone or wood (occasionally copper in the Andes), slings, bows and arrows, and quilted armor, constituting much less effective protection and weaponry. In addition, Native American armies had no animals to oppose to horses, whose value for assaults and fast transport gave Europeans an overwhelming advantage until some Native American societies themselves adopted them.

第二、欧亚大陆的军事技术比美洲的军事技术要有效能得多。欧洲的兵器是钢刀、长矛和匕首,辅以小型火器和火炮,而护身的盔甲也是由纯钢打就的,或是由锁子甲做成的。印第安人不用钢铁,他们用棍棒、用石制或木制的斧头(在安第斯山脉地区偶尔也有用铜制的)、投石器、弓箭和加软衬料缝制的盔甲,这些东西无论防护还是进攻,效果都差得多。另外,印第安军队没有任何可以与马匹相抗衡的牲口,而马匹在进攻和快速运输方面的价值使欧洲人获得了压倒的优势,直到有些印第安社会后来也采用了马匹。

Third, Eurasian societies enjoyed a huge advantage in their sources of power to operate machines. The earliest advance over human muscle power was the use of animals—cattle, horses, and donkeys—to pull plows and to turn wheels for grinding grain, raising water, and irrigating or draining fields. Waterwheels appeared in Roman times and then proliferated, along with tidal mills and windmills, in the Middle Ages. Coupled to systems of geared wheels, those engines harnessing water and wind power were used not only to grind grain and move water but also to serve myriad manufacturing purposes, including crushing sugar, driving blast furnace bellows, grinding ores, making paper, polishing stone, pressing oil, producing salt, producing textiles, and sawing wood. It is conventional to define the Industrial Revolution arbitrarily as beginning with the harnessing of steam power in 18th-century England, but in fact an industrial revolution based on water and wind power had begun already in medieval times in many parts of Europe. As of 1492, all of those operations to which animal, water, and wind power were being applied in Eurasia were still being carried out by human muscle power in the Americas.

第三、欧亚大陆社会在利用动力源运转机械方面拥有巨大的优势。超越人力的最早进展是利用动物——牛、马和驴——来拉犁耕地和转动轮子来磨谷、提水、灌溉或排水。水轮在罗马时代就已出现了,后来到了中世纪数量日渐增多,这时又出现了潮汐磨机和风车。这些利用水力和风力的机械和传动轮系统结合起来,不但被用来磨谷和运水,而且还可用于多种多样的制造目的,包括榨糖,为鼓风炉拉风箱,碾碎矿石,造纸,打磨石头,榨油,制盐,织布和锯木。习惯上都是把产业革命武断地定为从18世纪的英国利用蒸汽动力开始,但事实上一种以水力和风力为基础的产业革命在中世纪时就已在欧洲的许多地方开始了。直到1492年,所有这些在欧亚大陆用畜力、水力和风力来做的工作,在美洲仍旧靠人力来做。

Long before the wheel began to be used in power conversion in Eurasia, it had become the basis of most Eurasian land transport—not only for animal-drawn vehicles but also for human-powered wheelbarrows, which enabled one or more people, still using just human muscle power, to transport much greater weights than they could have otherwise. Wheels were also adopted in Eurasian pottery making and in clocks. None of those uses of the wheel was adopted in the Americas, where wheels are attested only in Mexican ceramic toys.

在轮子开始在欧亚大陆用于动力转换之前很久,轮子就已成为欧亚大陆大部分陆上运输的基础——不但用于牲口拉的车子,而且也用于靠人力来推的独轮车。独轮车使一个或更多的人即使仍旧靠自己的力量,也能搬动比不用独轮车时大得多的重量。轮子在欧亚大陆的制陶和时钟上也得到采用。轮子的这些用途没有一样在美洲得到采用,据考证在美洲采用轮子的只有墨西哥的陶瓷玩具。

The remaining area of technology to be mentioned is sea transport. Many Eurasian societies developed large sailing ships, some of them capable of sailing against the wind and crossing the ocean, equipped with sextants, magnetic compasses, sternpost rudders, and cannons. In capacity, speed, maneuverability, and seaworthiness, those Eurasian ships were far superior to the rafts that carried out trade between the New World's most advanced societies, those of the Andes and Mesoamerica. Those rafts sailed with the wind along the Pacific coast. Pizarro's ship easily ran down and captured such a raft on his first voyage toward Peru.

其余的值得一提的技术领域是海上运输。许多欧亚大陆社会发明了大型帆船,其中有些能逆风航行并能横渡大洋,船上装备有六分仪、磁罗盘、尾柱舵和大炮。无论在装载量、速度、机动性或是抗风浪能力方面,欧亚大陆的这些船只都比新大陆最先进的社会即安第斯山脉地区和中美洲的社会用来进行贸易的那些木筏优越得多。这些木筏靠风力沿太平洋海岸航行。皮萨罗的船在其前往秘鲁的首次航行中毫不费力地就撞翻并俘获了这样的一只木筏。

IN ADDITION TO their germs and technology, Eurasian and Native American societies differed in their political organization. By late medieval or Renaissance times, most of Eurasia had come under the rule of organized states. Among these, the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Chinese states, the Mogul state of India, and the Mongol state at its peak in the 13th century started out as large polyglot amalgamations formed by the conquest of other states. For that reason they are generally referred to as empires. Many Eurasian states and empires had official religions that contributed to state cohesion, being invoked to legitimize the political leadership and to sanction wars against other peoples. Tribal and band societies in Eurasia were largely confined to the Arctic reindeer herders, the Siberian hunter-gatherers, and the hunter-gatherer enclaves in the Indian subcontinent and tropical Southeast Asia.

除了在病菌和技术方面的差异外,欧亚大陆社会和印第安社会在政治组织方面也存在着差异。到中世纪晚期或文艺复兴时期,欧亚大陆的大部分地区已在有组织的国家的统治之下。其中的哈布斯堡王朝、奥斯曼帝国、中国的历代国家、印度的莫卧儿帝国和13世纪达到全盛时期的蒙古帝国,一开始就是通过征服其他国家而形成的多种语言的民族大融合。因此,它们通常被说成是帝国。许多欧亚大陆国家和帝国都有官方的宗教,用以加强国家的凝聚力,使政治领导合法化和批准对其他民族的战争。欧亚大陆的部落社会和族群社会,主要限于北极地区放牧驯鹿的牧人、西伯利亚狩猎采集族群、印度次大陆和热带东南亚狩猎采集族群的孤立小群体。

The Americas had two empires, those of the Aztecs and Incas, which resembled their Eurasian counterparts in size, population, polyglot makeup, official religions, and origins in the conquest of smaller states. In the Americas those were the sole two political units capable of mobilizing resources for public works or war on the scale of many Eurasian states, whereas seven European states (Spain, Portugal, England, France, Holland, Sweden, and Denmark) had the resources to acquire American colonies between 1492 and 1666. The Americas also held many chiefdoms (some of them virtually small states) in tropical South America, Mesoamerica beyond Aztec rule, and the U.S. Southeast. The rest of the Americas was organized only at the tribal or band level.

美洲有两个帝国:阿兹特克帝国和印加帝国。它们在面积、人口、语言的多种组成、官方宗教和征服小国的策源地等方面,与欧亚大陆的一些帝国相似。在美洲,这两个帝国是唯一的能够以许多欧亚大陆国家的那种规模调动人力物力兴建公共工程或进行战争的两个政治单位,而7个欧洲国家(西班牙、葡萄牙、英国、法国、荷兰、瑞典和丹麦)有能力从1492年到1666年在美洲建立殖民地。在美洲的热带南美地区、阿兹特克帝国统治范围以外的中美洲和美国东南部,也有许多酋长管辖地(其中有些几乎就是小小的国家)。美洲的其余地区只有一些部落和族群组织。

The last proximate factor to be discussed is writing. Most Eurasian states had literate bureaucracies, and in some a significant fraction of the populace other than bureaucrats was also literate. Writing empowered European societies by facilitating political administration and economic exchanges, motivating and guiding exploration and conquest, and making available a range of information and human experience extending into remote places and times. In contrast, use of writing in the Americas was confined to the elite in a small area of Mesoamerica. The Inca Empire employed an accounting system and mnemonic device based on knots (termed quipu), but it could not have approached writing as a vehicle for transmitting detailed information.

最后一个需要予以讨论的直接因素是文字。大多数欧亚大陆国家都有由有文化的人组成的行政机构,在某些国家里,官员以外的平民大众中也有相当一部分人是有文化的。文字使欧洲社会得到行政管理和经济交换之便,激励与指导探险和征服,并可利用远方和古代的一系列信息和人类经验。相比之下,在美洲,文字只在中美洲很小的一个地区内的上层人士中使用。印加帝国使用了一种以结绳(叫做基普)为基础的会计制度和记忆符号,但作为一种传递详细信息的手段,它还不可能起到文字的作用。

THUS, EURASIAN SOCIETIES in the time of Columbus enjoyed big advantages over Native American societies in food production, germs, technology (including weapons), political organization, and writing. These were the main factors tipping the outcome of the post-Columbian collisions. But those differences as of A.D. 1492 represent just one snapshot of historical trajectories that had extended over at least 13,000 years in the Americas, and over a much longer time in Eurasia. For the Americas, in particular, the 1492 snapshot captures the end of the independent trajectory of Native Americans. Let us now trace out the earlier stages of those trajectories.

因此,哥伦布时代的欧亚大陆社会,在粮食生产、病菌、技术(包括武器)、政治组织和文字方面,拥有对印第安社会的巨大优势。这些都是对哥伦布以后碰撞结果起决定性作用的主要因素。但到1492年为止的这些差异,只不过是历史轨迹上的一个快照镜头,而这个历史轨迹在美洲至少长达13000多年,在欧亚大陆时间还要长得多。尤其对美洲来说,1492年的这个快照镜头却拍下了印第安人这个独立轨迹的结尾。现在,让我们来描绘一下这些轨迹的各个早期阶段。

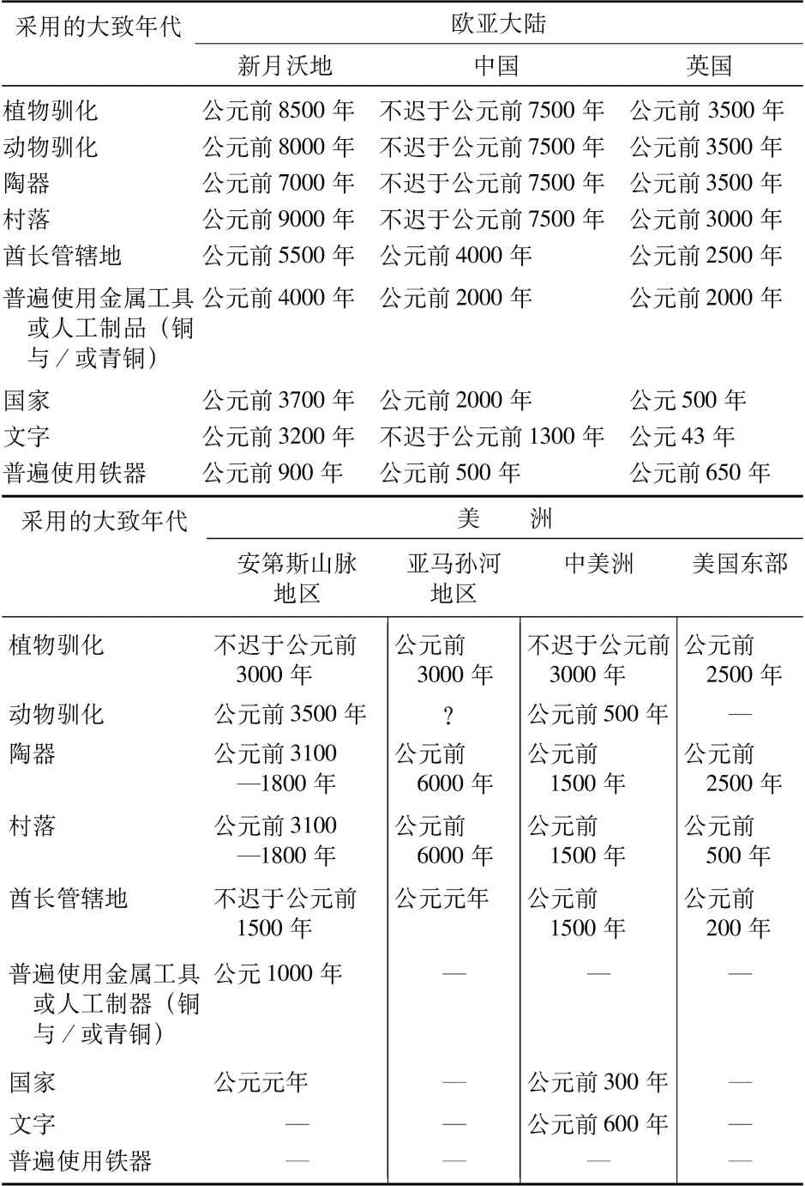

Table 18.1 summarizes approximate dates of the appearance of key developments in the main “homelands” of each hemisphere (the Fertile Crescent and China in Eurasia, the Andes and Amazonia and Mesoamerica in the Americas). It also includes the trajectory for the minor New World homeland of the eastern United States, and that for England, which is not a homeland at all but is listed to illustrate how rapidly developments spread from the Fertile Crescent.

表18.1概括地介绍了每个半球最大的“中心地”(欧亚大陆的新月沃地和中国,美洲的安第斯山脉地区、亚马孙河地区和中美洲)的主要发展成果出现的大致年代。表中还列出了美国东部这个新大陆较小的中心地的发展轨迹,也列出了英国的发展轨迹,因为英国虽然完全不是一个中心地,但把它列出来是为了说明发展成果从新月沃地向外传播的速度。

This table is sure to horrify any knowledgeable scholar, because it reduces exceedingly complex histories to a few seemingly precise dates. In reality, all of those dates are merely attempts to label arbitrary points along a continuum. For example, more significant than the date of the first metal tool found by some archaeologist is the time when a significant fraction of all tools was made of metal, but how common must metal tools be to rate as “widespread”? Dates for the appearance of the same development may differ among different parts of the same homeland. For instance, within the Andean region pottery appears about 1,300 years earlier in coastal Ecuador (3100 B.C.) than in Peru (1800 B.C.). Some dates, such as those for the rise of chiefdoms, are more difficult to infer from the archaeological record than are dates of artifacts like pottery or metal tools. Some of the dates in Table 18.1 are very uncertain, especially those for the onset of American food production. Nevertheless, as long as one understands that the table is a simplification, it is useful for comparing continental histories.

这个表肯定会使任何一个知识渊博的学者产生反感,因为它把极其复杂的历史变成了几个貌似准确的年代。其实,所有这些年代仅仅是为了把一个连续体上的一些任意的点标出来。例如,比某一个考古学家发现的第一件金属工具的年代更重要的,是所有工具中相当大一部分工具是用金属制造的时间,不过金属工具要有多普通才可被定为“普遍的”?同一发展成果出现的年代,在同一中心地的不同地区会有所不同。例如,安第斯山脉地区内厄瓜多尔沿海陶器出现的时间(公元前3100年)比在秘鲁(公元前1800年)早1300年左右。有些年代,如酋长管辖地出现的年代,要比陶器或金属工具之类的人工制品更难根据考古记录来推断。表18.1中的有些年代是很不确定的,尤其是美洲粮食生产开始的年代。不过,只要我们了解这张表是简化的结果,它对比较各个大陆的历史还是有用的。

The table suggests that food production began to provide a large fraction of human diets around 5,000 years earlier in the Eurasian homelands than in those of the Americas. A caveat must be mentioned immediately: while there is no doubt about the antiquity of food production in Eurasia, there is controversy about its onset in the Americas. In particular, archaeologists often cite considerably older claimed dates for domesticated plants at Coxcatlán Cave in Mexico, at Guitarrero Cave in Peru, and at some other American sites than the dates given in the table. Those claims are now being reevaluated for several reasons: recent direct radiocarbon dating of crop remains themselves has in some cases been yielding younger dates; the older dates previously reported were based instead on charcoal thought to be contemporaneous with the plant remains, but possibly not so; and the status of some of the older plant remains as crops or just as collected wild plants is uncertain. Still, even if plant domestication did begin earlier in the Americas than the dates shown in Table 18.1, agriculture surely did not provide the basis for most human calorie intake and sedentary existence in American homelands until much later than in Eurasian homelands.

这张表表明,粮食生产开始提供很大一部分的人类食物,在欧亚大陆的中心地要比在美洲的中心地早5000年左右。必须立即提醒的一点是:虽然欧亚大陆粮食生产年代之久远无可怀疑,但美洲粮食生产开始的时间却是有争论的。尤其是,考古学家们常常大量引用所宣布的早于表中所列年代的植物驯化的年代,发现这些植物的地方是墨西哥的科克斯卡特兰洞穴、秘鲁的吉塔里罗洞穴和美洲的其他一些考古遗址。这些宣布的年代现在正受到重新评价,这有几个原因:最近直接用碳-14对一些作物残存进行的测定,在有些情况下得出了较近的年代;以前所报道的较早的年代,是以遗址中一起出土的木炭为根据的,这些木炭被认为是与作物残存属于同一时期,但也可能不是;有些年代较早的植物残存,原来究竟是作物或只是采集来的野生植物,其身分还不能确定。不过,即使美洲植物驯化开始的时间早于表18.1所列的年代,美洲的农业无疑直到比欧亚大陆中心地晚得多的时候才为美洲中心地人类大部分卡路里的摄入和定居生活提供了基础。

As we saw in Chapters 5 and 10, only a few relatively small areas of each hemisphere acted as a “homeland” where food production first arose and from which it then spread. Those homelands were the Fertile Crescent and China in Eurasia, and the Andes and Amazonia, Mesoamerica, and the eastern United States in the Americas. The rate of spread of key developments is especially well understood for Europe, thanks to the many archaeologists at work there. As Table 18.1 summarizes for England, once food production and village living had arrived from the Fertile Crescent after a long lag (5,000 years), the subsequent lag for England's adoption of chiefdoms, states, writing, and especially metal tools was much shorter: 2,000 years for the first widespread metal tools of copper and bronze, and only 250 years for widespread iron tools. Evidently, it was much easier for one society of already sedentary farmers to “borrow” metallurgy from another such society than for nomadic hunter-gatherers to “borrow” food production from sedentary farmers (or to be replaced by the farmers).

我们在第五章和第十章中看到,每一个半球只有几个较小的地区充当“中心地”,粮食生产首先在那里出现,接着又从那里向外传播。这些中心地是欧亚大陆的新月沃地和中国,美洲的安第斯山脉地区、亚马孙河地区、中美洲和美国东部。由于有那许多考古学家在欧洲工作,一些主要发展结果的传播速度对欧洲来说尤其不言而喻。正如表18.1对英国概括介绍的那样,一旦粮食生产和村居生活在经过长期的迟滞(5000年)之后从新月沃地引进英国,随后英国采用酋长管辖地、国家、文字、尤其是金属工具的迟滞时间要短得多:最早普遍使用铜和青铜金属工具晚了2000年,而普遍使用铁器只晚了250年。显然,一个已经属于定居农民的社会向另一个这样的社会“借来”冶金术,要比四处流浪的狩猎采集族群向定居农民“借来”粮食生产(或被农民所取代)容易得多。

WHY WERE THE trajectories of all key developments shifted to later dates in the Americas than in Eurasia? Four groups of reasons suggest themselves: the later start, more limited suite of wild animals and plants available for domestication, greater barriers to diffusion, and possibly smaller or more isolated areas of dense human populations in the Americas than in Eurasia.

为什么所有主要发展结果的发展轨迹在年代上美洲要晚于欧亚大陆?这有4组原因:起步晚,可用于驯化的野生动植物系列比较有限,较大的传播障碍,以及稠密的人口在美洲生活的地区可能比在欧亚大陆小,或者可能比在欧亚大陆孤立。

As for Eurasia's head start, humans have occupied Eurasia for about a million years, far longer than they have lived in the Americas. According to the archaeological evidence discussed in Chapter 1, humans entered the Americas at Alaska only around 12,000 B.C., spread south of the Canadian ice sheets as Clovis hunters a few centuries before 11,000 B.C., and reached the southern tip of South America by 10,000 B.C., Even if the disputed claims of older human occupation sites in the Americas prove valid, those postulated pre-Clovis inhabitants remained for unknown reasons very sparsely distributed and did not launch a Pleistocene proliferation of hunter-gatherer societies with expanding populations, technology, and art as in the Old World. Food production was already arising in the Fertile Crescent only 1,500 years after the time when Clovis-derived hunter-gatherers were just reaching southern South America.

就欧亚大陆的领先优势来说,人类占领欧亚大陆已有大约100万年之久,比他们在美洲生活的时间长得多。根据第一章中讨论的考古证据,人类在阿拉斯加进入美洲不过在公元前12000年左右,作为克罗维猎人向加拿大冰原以南扩散是在公元前11000年前的几百年,而到达南美洲的南端不迟于公元前1万年。即使关于美洲存在更早的人类居住遗址的一些有争论的主张证明是有根据的,但由于某些未知的原因,这些假定存在的克罗维人以前的居民也只有很稀少的分布,不能像在旧大陆那样随着人口、技术和技艺的发展而在更新世使狩猎采集社会在数量上有巨大的增加。在源自克罗维人的狩猎采集族群到达南美洲南部后仅仅1500年,粮食生产便已在新月沃地出现了。

TABLE 18.1 Historical Trajectories of Eurasia and the Americas

表18.1欧亚大陆和美洲的历史轨迹

| Approximate Date of Adoption | Eurasia | |||

| Fertile Crescent | China | England | ||

| Plant domestication | 8500 B.C. | by 7500 B.C. | 3500 B.C. | |

| Animal domestication | 8000 B.C. | by 7500 B.C. | 3500 B.C. | |

| Pottery | 7000 B.C. | by 7500 B.C. | 3500 B.C. | |

| Villages | 9000 B.C. | by 7500 B.C. | 3000 B.C. | |

| Chiefdoms | 5500 B.C. | 4000 B.C. | 2500 B.C. | |

| Widespread metal tools or artifacts (copper and/or bronze) | 4000 B.C. | 2000 B.C. | 2000 B.C. | |

| States | 3700 B.C. | 2000 B.C. | 500 A.D. | |

| Writing | 3200 B.C. | by 1300 B.C. | A.D. 43 | |

| Widespread iron tools | 900 B.C. | 500 B.C. | 650 B.C. | |

| Approximate Date of Adoption | Native America | |||

| Andes | Amazonia | Mesoamerica | Eastern U.S. | |

| Plant domestication | by 3000 B.C. | 3000 B.C. | by 3000 B.C. | 2500 B.C. |

| Animal domestication | 3500 B.C. | ? | 500 B.C. | — |

| Pottery | 3100–1800 B.C. | 6000 B.C. | 1500 B.C. | 2500 B.C. |

| Villages | 3100–1800 B.C. | 6000 B.C. | 1500 B.C. | 500 B.C. |

| Chiefdoms | by 1500 B.C. | A.D. 1 | 1500 B.C. | 200 B.C. |

| Widespread metal tools or artifacts (copper and/or bronze) | A.D. 1000 | — | — | — |

| States | A.D. 1 | — | 300 B.C. | — |

| Writing | — | — | 600 B.C. | — |

| Widespread iron tools | — | — | — | — |

This table gives approximate dates of widespread adoption of significant developments in three Eurasian and four Native American areas. Dates for animal domestication neglect dogs, which were domesticated earlier than food-producing animals in both Eurasia and the Americas. Chiefdoms are inferred from archaeological evidence, such as ranked burials, architecture, and settlement patterns. The table greatly simplifies a complex mass of historical facts: see the text for some of the many important caveats.

本表所列为欧亚大陆3个地区与美洲4个地区普遍采用重要的发展结果的大致年代。动物驯化的年代未将狗包括在内,因为无论是在欧亚大陆还是在美洲,狗的驯化都要早于从事粮食生产的动物。酋长管辖地是从考古证据推断出来的,如分等级的墓葬、建筑物和居所的形制。本表将大量复杂的历史事实简化了:关于许多重要的说明,有些可参见正文。

Several possible consequences of that Eurasian head start deserve consideration. First, could it have taken a long time after 11,000 B.C. for the Americas to fill up with people When one works out the likely numbers involved, one finds that this effect would make only a trivial contribution to the Americas' 5,000-year lag in food-producing villages. The calculations given in Chapter 1 tell us that even if a mere 100 pioneering Native Americans had crossed the Canadian border into the lower United States and increased at a rate of only 1 percent per year, they would have saturated the Americas with hunter-gatherers within 1,000 years. Spreading south at a mere one mile per month, those pioneers would have reached the southern tip of South America only 700 years after crossing the Canadian border. Those postulated rates of spread and of population increase are very low compared with actual known rates for peoples occupying previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited lands. Hence the Americas were probably fully occupied by hunter-gatherers within a few centuries of the arrival of the first colonists.

欧亚大陆的这种领先优势的几个可能的结果值得考虑。首先,在公元前11000年后,人类是否花了很长时间才完全占据了美洲?只要能算出有关的可靠数字,就会发现这一结果对于造成美洲生产粮食的村庄晚5000年出现这一局面只有微乎其微的影响。第一章中所作的计算告诉我们,即使只有100个成为开路先锋的印第安人越过加拿大边界,进入美国南部,并以每年1%的速度增加,那么不出1000年,他们所形成的狩猎采集人口可能已布满了整个美洲。这些开路先锋如果每月向南只前进一英里,那么他们在越过加拿大边界后只需700年就已到达南美洲的南端。同人们占据先前无人居住或居民稀少地区的已知的实际速度相比,这里所假设的人口扩散和人口增长的速度是非常低的。因此,美洲可能是在第一批移民到达后的几个世纪内就被狩猎采集族群全部占领了。

Second, could a large part of the 5,000-year lag have represented the time that the first Americans required to become familiar with the new local plant species, animal species, and rock sources that they encountered? If we can again reason by analogy with New Guinean and Polynesian hunter-gatherers and farmers occupying previously unfamiliar environments—such as Maori colonists of New Zealand or Tudawhe colonists of New Guinea's Karimui Basin—the colonists probably discovered the best rock sources and learned to distinguish useful from poisonous wild plants and animals in much less than a century.

其次,在这滞后的5000年中,会不会有很大一部分时间是最早的美洲人必须用来熟悉他们所碰到的当地动植物新品种和石料?新几内亚和波利尼西亚的狩猎采集族群和农民也曾占据了原来不熟悉的环境,如新西兰的毛利人移民或新几内亚开利莫伊盆地的图达辉移民。如果我们能以这些人为例,再一次用类比办法进行推理,那么美洲的这些移民大概在远远不到一个世纪的时间内也发现了最好的石料,并学会了把有用的野生动植物和有毒的野生动植物区别开来。

Third, what about Eurasians' head start in developing locally appropriate technology? The early farmers of the Fertile Crescent and China were heirs to the technology that behaviorially modern Homo sapiens had been developing to exploit local resources in those areas for tens of thousands of years. For instance, the stone sickles, underground storage pits, and other technology that hunter-gatherers of the Fertile Crescent had been evolving to utilize wild cereals were available to the first cereal farmers of the Fertile Crescent. In contrast, the first settlers of the Americas arrived in Alaska with equipment appropriate to the Siberian Arctic tundra. They had to invent for themselves the equipment suitable to each new habitat they encountered. That technology lag may have contributed significantly to the delay in Native American developments.

第三,欧亚大陆人在发展适合本地的技术方面的领先优势,情况又是如何呢?新月沃地和中国的早期农民是这种技术的继承者,而这种技术是行为上的现代智人几万年来为利用这些地区的当地资源而发展起来的。例如,石镰、地下窖藏穴以及新月沃地的狩猎采集族群为了利用野生谷物而逐步发展起来的其他技术,对新月沃地最早的生产谷物的农民来说都是现成可用的。相比之下,美洲的最早移民在到达阿拉斯加时所带来的只是适合在西伯利亚北极地区冻原使用的设备。他们每到一处,都得为自己发明适合新环境的设备。这种技术上的滞后可能对印第安人发展的迟缓起了重大的作用。

An even more obvious factor behind the delay was the wild animals and plants available for domestication. As I discussed in Chapter 6, when hunter-gatherers adopt food production, it is not because they foresee the potential benefits awaiting their remote descendants but because incipient food production begins to offer advantages over the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Early food production was less competitive with hunting-gathering in the Americas than in the Fertile Crescent or China, partly owing to the Americas' virtual lack of domesticable wild mammals. Hence early American farmers remained dependent on wild animals for animal protein and necessarily remained part-time hunter-gatherers, whereas in both the Fertile Crescent and China animal domestication followed plant domestication very closely in time to create a food producing package that quickly won out over hunting-gathering. In addition, Eurasian domestic animals made Eurasian agriculture itself more competitive by providing fertilizer, and eventually by drawing plows.

造成这种迟缓的一个甚至更明显的因素,是可以用于驯化的野生动植物。我在第六章中讨论过,狩猎采集族群之所以采纳粮食生产,不是因为那可能会给他们的子孙后代带来好处,而是因为早期的粮食生产开始显示了对狩猎采集生活方式的优势。早期的粮食生产与狩猎采集活动的竞争,在美洲不及在新月沃地和中国那样激烈,这一部分是由于美洲几乎没有可以驯化的野生哺乳动物。因此,早期的美洲农民仍然依靠野生动物来获得动物蛋白,所以必定以一部分时间仍然去从事狩猎采集活动,而在新月沃地和中国,植物驯化之后紧接着就是动物驯化,这样就及时地发展出全套粮食生产,最后取得了对狩猎采集活动的胜利。此外,欧亚大陆的家畜通过提供粪肥并最后通过拉犁使欧亚大陆的农业更具竞争力。

Features of American wild plants also contributed to the lesser competitiveness of Native American food production. That conclusion is clearest for the eastern United States, where less than a dozen crops were domesticated, including small-seeded grains but no large-seeded grains, pulses, fiber crops, or cultivated fruit or nut trees. It is also clear for Mesoamerica's staple grain of corn, which spread to become a dominant crop elsewhere in the Americas as well. Whereas the Fertile Crescent's wild wheat and barley evolved into crops with minimal changes and within a few centuries, wild teosinte may have required several thousand years to evolve into corn, having to undergo drastic changes in its reproductive biology and energy allocation to seed production, loss of the seed's rock-hard casings, and an enormous increase in cob size.

美洲野生植物的特点也是印第安人粮食生产竞争力差的一个原因。这个结论在美国东部看得最为清晰,因为那里只有靠10种是驯化的,包括小籽粒的谷物而没有大籽粒的谷物,还有豆类植物、纤维作物,或栽培的水果树或坚果树。这对中美洲的主要作物玉米也是很清楚的,因为玉米的传播使它也成了美洲其他地方的主要作物。虽然新月沃地的野生小麦和大麦在几个世纪内几乎没有什么改变就演化成作物,但野生的墨西哥类蜀黍可能需要几千年的时间才能演化成作物,同时必须在繁殖生物学和对结籽的能量分配方面经历巨大的变化,使种子失去坚硬的外壳并大大增加玉米棒子的尺寸。

As a result, even if one accepts the recently postulated later dates for the onset of Native American plant domestication, about 1,500 or 2,000 years would have elapsed between that onset (about 3000–2500 B.C.) and widespread year-round villages (1800–500 B.C.) in Mesoamerica, the inland Andes, and the eastern United States. Native American farming served for a long time just as a small supplement to food acquisition by hunting-gathering, and supported only a sparse population. If one accepts the traditional, earlier dates for the onset of American plant domestication, then 5,000 years instead of 1,500 or 2,000 years elapsed before food production supported villages. In contrast, villages were closely associated in time with the rise of food production in much of Eurasia. (The hunter-gatherer lifestyle itself was sufficiently productive to support villages even before the adoption of agriculture in parts of both hemispheres, such as Japan and the Fertile Crescent in the Old World, and coastal Ecuador and Amazonia in the New World.) The limitations imposed by locally available domesticates in the New World are well illustrated by the transformations of Native American societies themselves when other crops or animals arrived, whether from elsewhere in the Americas or from Eurasia. Examples include the effects of corn's arrival in the eastern United States and Amazonia, the llama's adoption in the northern Andes after its domestication to the south, and the horse's appearance in many parts of North and South America.

因此,即使接受关于美洲植物驯化开始年代较晚的假定,在中美洲、安第斯山脉地区的内陆和美国东部,从植物驯化开始(公元前3000—2500年左右)到普遍出现终年定居的村落(公元前1800—500年),中间可能经过了大约1500年或2000年。美洲的农业长期以来在获得食物方面只是对狩猎采集的一个小小的补充,只能养活稀少的人口。如果接受关于美洲植物驯化开始年代较早的传统说法,那么粮食生产经过了5000年而不是1500年或2000年才维持了终年定居的村落。相比之下,在欧亚大陆的很大一部分地区,村落的出现在时间上是和粮食生产的出现紧密地联系在一起的。(狩猎采集生活方式本身相当富有成效,足以维持定居的村落,在这两个半球的一些地方,如旧大陆的日本和新月沃地,新大陆的厄瓜多尔沿海和亚马孙河地区,甚至在采用农业前便已有村落存在了。)对新大陆本地现有的驯化动植物所造成的限制的最好说明,就是美洲社会本身在别的作物或动物引进时所发生的变化,不管这些作物或动物来自美洲的其他地方,还是来自欧亚大陆。这方面的例子有玉米引进美国东部和亚马孙河地区所产生的影响,有美洲驼在安第斯山脉地区的南部驯化后被安第斯山脉地区的北部所采纳,还有马在北美洲和南美洲的许多地方出现。

In addition to Eurasia's head start and wild animal and plant species, developments in Eurasia were also accelerated by the easier diffusion of animals, plants, ideas, technology, and people in Eurasia than in the Americas, as a result of several sets of geographic and ecological factors. Eurasia's east-west major axis, unlike the Americas' north-south major axis, permitted diffusion without change in latitude and associated environmental variables. In contrast to Eurasia's consistent east-west breadth, the New World was constricted over the whole length of Central America and especially at Panama. Not least, the Americas were more fragmented by areas unsuitable for food production or for dense human populations. These ecological barriers included the rain forests of the Panamanian isthmus separating Mesoamerican societies from Andean and Amazonian societies; the deserts of northern Mexico separating Mesoamerica from U.S. southwestern and southeastern societies; dry areas of Texas separating the U.S. Southwest from the Southeast; and the deserts and high mountains fencing off U.S. Pacific coast areas that would otherwise have been suitable for food production. As a result, there was no diffusion of domestic animals, writing, or political entities, and limited or slow diffusion of crops and technology, between the New World centers of Mesoamerica, the eastern United States, and the Andes and Amazonia.

除了欧亚大陆的领先优势和野生动植物品种外,欧亚大陆发展速度的加快也由于在欧亚大陆动物、植物、思想、技术和人员的交流比在美洲容易,而交流容易又是由于存在几组地理和生态因素的结果。与美洲的南北主轴不同,欧亚大陆的东西主轴使这种交流不用经历纬度的变化,也不存在与环境的变量发生关系的问题。与欧亚大陆始终如一的东西宽度不同,新大陆在中美洲的那一段特别是在巴拿马变窄了。尤其是,美洲被一些不适于粮食生产也不适于稠密人口的地区分割开来。这些生态障碍包括:把中美洲社会同安第斯山脉地区和亚马孙河地区社会分隔开来的巴拿马地峡雨林;把中美洲社会同美国西南部和东南部社会分隔开来的墨西哥北部沙漠;把美国西南部同东南部分隔开来的得克萨斯州干旱地区;以及把本来可能适于粮食生产的美国太平洋沿岸地区隔开的沙漠和高山。因此,在中美洲、美国东部、安第斯山脉地区和亚马孙河地区这些新大陆的中心之间,完全没有家畜、文字和政治实体方面的交流,以及只有在作物和技术方面的有限的缓慢的交流。

Some specific consequences of these barriers within the Americas deserve mention. Food production never diffused from the U.S. Southwest and Mississippi Valley to the modern American breadbaskets of California and Oregon, where Native American societies remained hunter-gatherers merely because they lacked appropriate domesticates. The llama, guinea pig, and potato of the Andean highlands never reached the Mexican highlands, so Mesoamerica and North America remained without domestic mammals except for dogs. Conversely, the domestic sunflower of the eastern United States never reached Mesoamerica, and the domestic turkey of Mesoamerica never made it to South America or the eastern United States. Mesoamerican corn and beans took 3,000 and 4,000 years, respectively, to cover the 700 miles from Mexico's farmlands to the eastern U.S. farmlands. After corn's arrival in the eastern United States, seven centuries more passed before the development of a corn variety productive in North American climates triggered the Mississippian emergence. Corn, beans, and squash may have taken several thousand years to spread from Mesoamerica to the U.S. Southwest. While Fertile Crescent crops spread west and east sufficiently fast to preempt independent domestication of the same species or else domestication of closely related species elsewhere, the barriers within the Americas gave rise to many such parallel domestications of crops.

美洲范围内的这些障碍的某些特有的后果值得一提。粮食生产从未从美国西南部和密西西比河河谷向美国现代的粮仓加利福尼亚和俄勒冈传播,那里的印第安社会仅仅由于缺乏合适的驯化动植物而仍然过着狩猎采集生活。安第斯山脉高原地区的美洲驼、豚鼠和马铃薯从未到达墨西哥高原,因此,中美洲和北美洲除了狗始终没有别的驯养的哺乳动物。反过来,美国东南部栽培的向日葵也从未到达过中美洲,而中美洲驯养的火鸡也从未到过南美洲或美国东部。中美洲的玉米和豆类分别花了3000年和4000年走完了从墨西哥农田到美国东部农田的700英里距离。在玉米引进美国东部后,又过了700年,在北美气候条件下培育的一种高产玉米促使密西西比河谷产粮地的兴起。玉米、豆类和南瓜可能用了几千年的时间才从中美洲传播到美国西南部。虽然新月沃地作物往东西两个方向传播的速度相当迅速,预先排除了同一品种植物独立驯化的机会,要不然就是预先排除其他地方亲缘相近植物驯化的机会,但美洲的那些障碍导致了作物有许多这样的平行驯化的机会。

As striking as these effects of barriers on crop and livestock diffusion are the effects on other features of human societies. Alphabets of ultimately eastern Mediterranean origin spread throughout all complex societies of Eurasia, from England to Indonesia, except for areas of East Asia where derivatives of the Chinese writing system took hold. In contrast, the New World's sole writing systems, those of Mesoamerica, never spread to the complex Andean and eastern U.S. societies that might have adopted them. The wheels invented in Mesoamerica as parts of toys never met the llamas domesticated in the Andes, to generate wheeled transport for the New World. From east to west in the Old World, the Macedonian Empire and the Roman Empire both spanned 3,000 miles, the Mongol Empire 6,000 miles. But the empires and states of Mesoamerica had no political relations with, and apparently never even heard of, the chiefdoms of the eastern United States 700 miles to the north or the empires and states of the Andes 1,200 miles to the south.

与生态障碍对作物和牲畜传播的这种种影响同样引人注目的,是其对人类社会其他特点的影响。最后起源于东地中海的字母从英格兰到印度尼西亚,传遍了欧亚大陆的各个复杂社会,只有东亚地区是例外,因为中国书写系统派生出来的文字已在那里占主导地位。相形之下,新大陆唯一的书写系统——中美洲的那些书写系统,从未传播到本来是会采用它们的安第斯山脉地区和美国东部的复杂社会。在中美洲作为玩具的零件而发明出来的轮子,从未与安第斯山脉地区驯化出来的美洲驼碰头,以便为新大陆产生装有轮子的运输工具。在旧大陆从东到西,马其顿帝国和罗马帝国横跨3000英里,而蒙古帝国则略地6000英里。但中美洲的帝国和国家则与北面700英里的美国东部的酋长管辖地,或南面1200英里的安第斯山脉地区的帝国和国家,没有任何政治关系,而且显然甚至没有听说过它们。

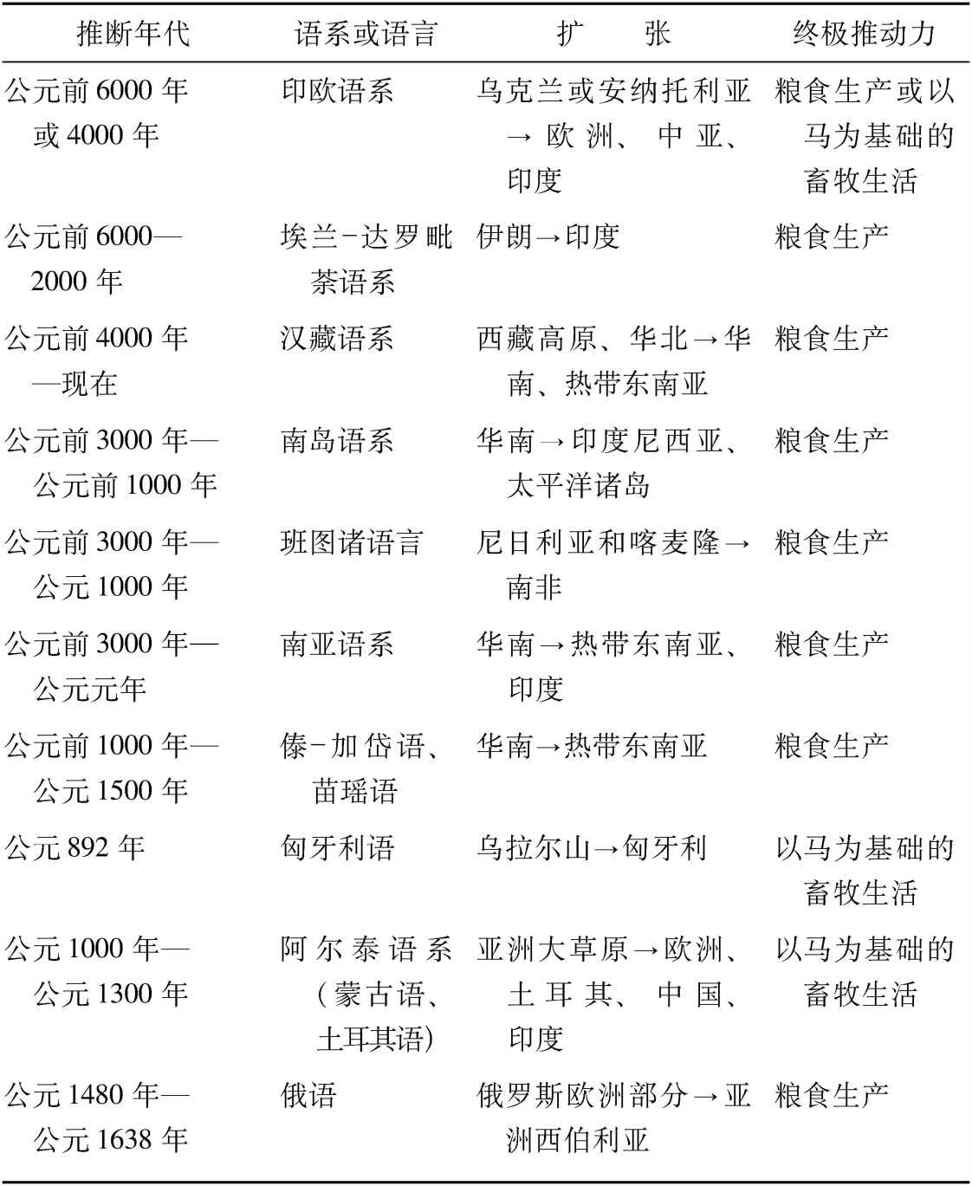

The greater geographic fragmentation of the Americas compared with Eurasia is also reflected in distributions of languages. Linguists agree in grouping all but a few Eurasian languages into about a dozen language families, each consisting of up to several hundred related languages. For example, the Indo-European language family, which includes English as well as French, Russian, Greek, and Hindi, comprises about 144 languages. Quite a few of those families occupy large contiguous areas—in the case of Indo-European, the area encompassing most of Europe east through much of western Asia to India. Linguistic, historical, and archaeological evidence combines to make clear that each of these large, contiguous distributions stems from a historical expansion of an ancestral language, followed by subsequent local linguistic differentiation to form a family of related languages (Table 18.2). Most such expansions appear to be attributable to the advantages that speakers of the ancestral language, belonging to food-producing societies, held over hunter-gatherers. We already discussed such historical expansions in Chapters 16 and 17 for the Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, and other East Asian language families. Among major expansions of the last millennium are those that carried Indo-European languages from Europe to the Americas and Australia, the Russian language from eastern Europe across Siberia, and Turkish (a language of the Altaic family) from Central Asia westward to Turkey.

与欧亚大陆相比,美洲在地理上更为支离破碎这种状况也在语言的分布上反映了出来。语言学家们一致同意,欧亚大陆的语言除几种外,可以分为大约十几个语系,每一个语系包括多达几百种亲属语言。例如,印欧语系不但包括法语、俄语、希腊语和印地语,而且也包括英语,这个语系由大约144种语言组成。在这些语系中,只有很少几个语系分布在大片的相邻地区内——就印欧语系来说,它所分布的地区包括欧洲的大部分,再向东经过西亚很大一部分地区到达印度。把语言的、历史的和考古的证据结合起来就可清楚地看出,语言的每一个这样的大片的相邻分布,起源于某一祖代语言在历史上的扩张,随后又由于地方性的语言分化而形成了一个由亲属语言组成的语系(表18.2)。大多数这样的扩张似乎可以归因于粮食生产社会中说这一祖代语言的人对狩猎采集族群所拥有的优势。我们在第十六章和第十七章中已经讨论过汉藏语系、南岛语系和其他东亚语系在历史上的这种扩张。在过去1000年里主要的一些语言扩张中,有把印欧语从欧洲带到美洲和澳大利亚的语言扩张,有把俄语从欧洲东部带到整个西伯利亚的语言扩张,还有把土耳其语(阿尔泰语系中的一种语言)从中亚向西带到土耳其的语言扩张。

With the exception of the Eskimo-Aleut language family of the American Arctic and the Na-Dene language family of Alaska, northwestern Canada, and the U.S. Southwest, the Americas lack examples of large-scale language expansions widely accepted by linguists. Most linguists specializing in Native American languages do not discern large, clear-cut groupings other than Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene. At most, they consider the evidence sufficient only to group other Native American languages (variously estimated to number from 600 to 2,000) into a hundred or more language groups or isolated languages. A controversial minority view is that of the linguist Joseph Greenberg, who groups all Native American languages other than Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene languages into a single large family, termed Amerind, with about a dozen subfamilies.

除了美洲北极地区的爱斯基摩-阿留申语系和阿拉斯加、加拿大西北部与美国西南部的纳迪尼语系,美洲没有为语言学家普遍承认的大规模语言扩张的例子。专门研究印第安语言的大多数语言学家,除了爱斯基摩语系和纳迪尼语系,看不出还有其他大的明确的语言分类。他们最多认为,现有证据只够把其他印第安语言(估计的数目从600种到2000种各不相同)分为100个或更多的语族或孤立的语言。一个有争议的属于少数派的观点,是语言学家约瑟夫·格林伯格所持有的观点,他把爱斯基摩-阿留申诸语言和纳迪尼诸语言以外的所有印第安语言归入一个大语系叫做美印语系,包括大约十几个语族。

Some of Greenberg's subfamilies, and some groupings recognized by more-traditional linguists, may turn out to be legacies of New World population expansions driven in part by food production. These legacies may include the Uto-Aztecan languages of Mesoamerica and the western United States, the Oto-Manguean languages of Mesoamerica, the Natchez-Muskogean languages of the U.S. Southeast, and the Arawak languages of the West Indies. But the difficulties that linguists have in agreeing on groupings of Native American languages reflect the difficulties that complex Native American societies themselves faced in expanding within the New World. Had any food-producing Native American peoples succeeded in spreading far with their crops and livestock and rapidly replacing hunter-gatherers over a large area, they would have left legacies of easily recognized language families, as in Eurasia, and the relationships of Native American languages would not be so controversial.

格林伯格的这些语族中的某些语族,以及得到比较传统的语言学家承认的某些语言分类,可能证明是在某种程度上由粮食生产推动的人口扩张的遗产。这些遗产可能包括中美洲和美国西部的犹他-阿兹特克诸语言、中美洲的奥托-曼格安诸语言、美国东南部的纳齐兹-马斯科吉诸语言,以及西印度群岛的阿拉瓦克诸语言。但语言学家们在商定对印第安诸语言进行分类时所碰到的困难,反映了印第安复杂社会本身在新大陆扩张时所碰到的困难。如果任何从事粮食生产的印第安族群带着他们的作物和牲口成功地向远处扩张,并在广大地区内迅速取代狩猎采集族群,他们可能会留下如同我们在欧亚大陆看到的那样容易辨认的语系遗产,而印第安诸语言之间的关系也就不会那样引起争论了。

TABLE 18.2 Language Expansions in the Old World

表18.2 旧大陆的语言扩张

| Inferred Date | Language Family or Language | Expansion | Ultimate Driving Force |

| 6000 or 4000 B.C. |

Indo-European | Ukraine or Anatolia | food production or horse-based pastoralism |

| Europe, C. Asia, India | |||

| 6000 B.C.–2000 B.C. | Elamo-Dravidian | Iran | food production |

| India | |||

| 4000 B.C.–present | Sino-Tibetan | Tibetan Plateau, N. China |

food production |

| S. China, tropical S.E. Asia | |||

| 3000 B.C.–1000 B.C. | Austronesian | S. China | food production |

| Indonesia, Pacific islands | |||

| 3000 B.C.–A.D. 1000 | Bantu | Nigeria and Cameroon | food production |

| S. Africa | |||

| 3000 B.C.–A.D. 1 | Austroasiatic | S. China | food production |

| tropical S.E. Asia, India | |||

| 1000 B.C.–A.D. 1500 | Tai-Kadai, Miao-Yao |

S. China | food production |

| tropical S.E. Asia | |||

| A.D. 892 | Hungarian | Ural Mts. | horse-based pastoralism |

| Hungary | |||

| A.D. 1000–A.D. 1300 | Altaic (Mongol, Turkish) |

Asian steppes | horse-based pastoralism |

| Europe, Turkey, China, India | |||

| A.D. 1480–A.D. 1638 | Russian | European Russia | food production |

| Asiatic Siberia |

Thus, we have identified three sets of ultimate factors that tipped the advantage to European invaders of the Americas: Eurasia's long head start on human settlement; its more effective food production, resulting from greater availability of domesticable wild plants and especially of animals; and its less formidable geographic and ecological barriers to intracontinental diffusion. A fourth, more speculative ultimate factor is suggested by some puzzling non-inventions in the Americas: the non-inventions of writing and wheels in complex Andean societies, despite a time depth of those societies approximately equal to that of complex Mesoamerican societies that did make those inventions; and wheels' confinement to toys and their eventual disappearance in Mesoamerica, where they could presumably have been useful in human-powered wheelbarrows, as in China. These puzzles remind one of equally puzzling non-inventions, or else disappearances of inventions, in small isolated societies, including Aboriginal Tasmania, Aboriginal Australia, Japan, Polynesian islands, and the American Arctic. Of course, the Americas in aggregate are anything but small: their combined area is fully 76 percent that of Eurasia, and their human population as of A.D. 1492 was probably also a large fraction of Eurasia's. But the Americas, as we have seen, are broken up into “islands” of societies with tenuous connections to each other. Perhaps the histories of Native American wheels and writing exemplify the principles illustrated in a more extreme form by true island societies.

因此,我们已经找到了3组有利于欧洲人入侵美洲的终极因素:欧亚大陆人类定居时间长的领先优势;由于欧亚大陆可驯化的野生植物尤其是动物的资源比较丰富而引起的比较有效的粮食生产;以及欧亚大陆范围内对传播交流的地理和生态障碍并非那样难以克服。第四个、也是更具推测性的终极因素,是根据美洲的一些令人费解的没有发明的东西而提出来的:安第斯山脉地区的复杂社会没有发明文字和轮子,虽然这些社会同作出这些发明的中美洲复杂社会在时间上差不多一样久远;轮子只用在玩具上并且后来竟在中美洲失传了,而推测起来轮子在中美洲是会像在中国一样用在人力独轮车上的。这些谜使人想起了在一些孤立的小社会中同样令人费解的要么没有发明要么发明了又失传了的情况,这些社会包括塔斯马尼亚土著社会、澳大利亚土著社会、日本、波利尼西亚诸岛和美洲北极地区。当然,美洲的面积加起来并不算小:整整占欧亚大陆面积的76%,美洲的整个人口到1492年止大概也相当于欧亚大陆人口的很大一部分。但我们已经看到,美洲被分割成一些社会“孤岛”,彼此之间几乎没有什么联系。也许,美洲的轮子和文字的历史,反映了真正的孤岛社会以一种比较极端的形式来予以说明的那些原则。

AFTER AT LEAST 13,000 years of separate developments, advanced American and Eurasian societies finally collided within the last thousand years. Until then, the sole contacts between human societies of the Old and the New Worlds had involved the hunter-gatherers on opposite sides of the Bering Strait.

在各自独立发展了至少13000年之后,先进的美洲和欧亚大陆社会终于在过去的几千年中发生了碰撞。在这之前,新旧大陆人类社会的唯一接触一直是白令海峡两边狩猎采集族群的接触。

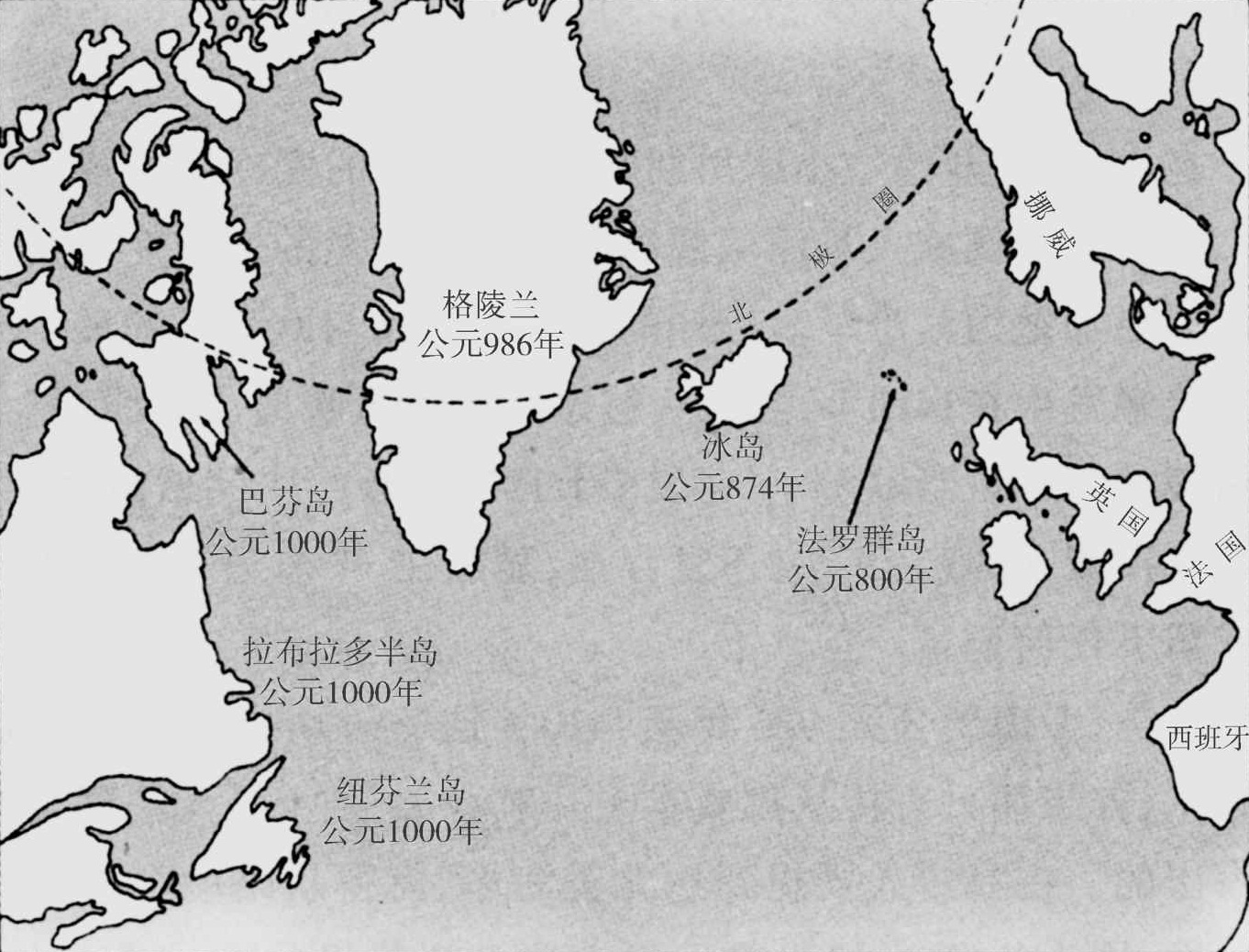

There were no Native American attempts to colonize Eurasia, except at the Bering Strait, where a small population of Inuit (Eskimos) derived from Alaska established itself across the strait on the opposite Siberian coast. The first documented Eurasian attempt to colonize the Americas was by the Norse at Arctic and sub-Arctic latitudes (Figure 18.1). Norse from Norway colonized Iceland in A.D. 874, then Norse from Iceland colonized Greenland in A.D. 986, and finally Norse from Greenland repeatedly visited the northeastern coast of North America between about A.D. 1000 and 1350. The sole Norse archaeological site discovered in the Americas is on Newfoundland, possibly the region described as Vinland in Norse sagas, but these also mention landings evidently farther north, on the coasts of Labrador and Baffin Island.

没有任何美洲人试图向欧亚大陆移民,只有一小批来自阿拉斯加的伊努伊特人(爱斯基摩人)渡过了白令海峡,在海峡对面的西伯利亚海岸定居下来。最早有文献证明的试图向美洲移民的是北极地区和亚北极纬度地区的古挪威人(图18.1)。古挪威人于公元874年从挪威向冰岛移民,然后于公元986年从冰岛向格陵兰移民,最后从大约公元1000年到1350年屡屡到达北美洲的东北部海岸。在美洲发现的唯一的关于古挪威人的考古遗址是在纽芬兰岛上,可能就是古挪威人传说中的文兰地区,但这些传说还提到了一些显然还要更北面的登陆地点,就是在拉布拉多海岸和巴芬岛的一些地方。

Figure 18.1. The Norse expansion from Norway across the North Atlantic, with dates or approximate dates when each area was reached.

图18.1 古挪威人从挪威横渡北大西洋的扩张,附有到达每一地区的年代或大致年代。

Iceland's climate permitted herding and extremely limited agriculture, and its area was sufficient to support a Norse-derived population that has persisted to this day. But most of Greenland is covered by an ice cap, and even the two most favorable coastal fjords were marginal for Norse food production. The Greenland Norse population never exceeded a few thousand. It remained dependent on imports of food and iron from Norway, and of timber from the Labrador coast. Unlike Easter Island and other remote Polynesian islands, Greenland could not support a self-sufficient food-producing society, though it did support self-sufficient Inuit hunter-gatherer populations before, during, and after the Norse occupation period. The populations of Iceland and Norway themselves were too small and too poor for them to continue their support of the Greenland Norse population.

冰岛的气候使放牧和极其有限的农业成为可能,它的面积也够大,足以养活源自古挪威人而一直绵延到今天的人口。但格陵兰的大部分地区都覆盖着冰帽,甚至那两个条件最好的海岸边的峡湾也只能让古挪威人进行最起码的粮食生产。格陵兰的古挪威人口从未超过几千。它始终依靠从挪威运进粮食和铁器,从拉布拉多沿海运进木材。与复活节岛和其他偏远的波利尼西亚岛屿不同,格陵兰无法维持一个自给自足的进行粮食生产的社会,虽然它在古挪威人占领之前、占领期间和占领结束之后,确曾养活了一些自给自足的伊努伊特狩猎采集群体。冰岛和挪威本身的人口太少、太穷,不可能继续养活格陵兰的古挪威人口。

In the Little Ice Age that began in the 13th century, the cooling of the North Atlantic made food production in Greenland, and Norse voyaging to Greenland from Norway or Iceland, even more marginal than before. The Greenlanders' last known contact with Europeans came in 1410 with an Icelandic ship that arrived after being blown off course. When Europeans finally began again to visit Greenland in 1577, its Norse colony no longer existed, having evidently disappeared without any record during the 15th century.

在13世纪开始的小冰川期间,北大西洋的变冷使格陵兰的粮食生产和古挪威人从挪威或冰岛前往格陵兰的航行变得甚至比以前更加勉为其难了。已知的格陵兰岛民与欧洲人的最早的一次接触发生在1410年,当时一艘冰岛船被风吹离了航线,靠上了格陵兰海岸。当欧洲人最后又于1577年开始访问格陵兰时,岛上古挪威人的殖民地已不复存在,显然在15世纪便已消失而没有留下任何记录。

But the coast of North America lay effectively beyond the reach of ships sailing directly from Norway itself, given Norse ship technology of the period A.D. 986–1410. The Norse visits were instead launched from the Greenland colony, separated from North America only by the 200-mile width of Davis Strait. However, the prospect of that tiny marginal colony's sustaining an exploration, conquest, and settlement of the Americas was nil. Even the sole Norse site located on Newfoundland apparently represents no more than a winter camp occupied by a few dozen people for a few years. The Norse sagas describe attacks on their Vinland camp by people termed Skraelings, evidently either Newfoundland Indians or Dorset Eskimos.

但是,考虑到公元986年至1410年这一时期古挪威人的造船技术,如果船只直接从挪威本土开航,那事实上是无法到达北美海岸的。古挪威人要想到达北美海岸,就得从格陵兰的殖民地出发,因为格陵兰与北美只隔着宽200英里的戴维斯海峡。然而,要使这样一个勉强够格的殖民地去支持对美洲的探险、征服和殖民,其希望等于零。甚至位于纽芬兰的古挪威人的唯一遗址,显然不过是几十个人住过几年的一个过冬的营地。古挪威人的传说描写了他们在文兰的营地遭到叫做斯克里林人的袭击,显然这些人或者是纽芬兰的印第安人,或者是多西特爱斯基摩人。

The fate of the Greenland colony, medieval Europe's most remote outpost, remains one of archaeology's romantic mysteries. Did the last Greenland Norse starve to death, attempt to sail off, intermarry with Eskimos, or succumb to disease or Eskimo arrows? While those questions of proximate cause remain unanswered, the ultimate reasons why Norse colonization of Greenland and America failed are abundantly clear. It failed because the source (Norway), the targets (Greenland and Newfoundland), and the time (A.D. 984–1410) guaranteed that Europe's potential advantages of food production, technology, and political organization could not be applied effectively. At latitudes too high for much food production, the iron tools of a few Norse, weakly supported by one of Europe's poorer states, were no match for the stone, bone, and wooden tools of Eskimo and Indian hunter-gatherers, the world's greatest masters of Arctic survival skills.

中世纪欧洲最遥远的前哨基地纽芬兰殖民地的命运,始终是考古学的传奇性的神秘事件之一。格陵兰的最后一批古挪威人是饿死了呢,是试图扬帆远去了呢,是与爱斯基摩人通婚,或是死于疾病或爱斯基摩人的弓箭之下呢?虽然这些关于直接原因的问题仍然无法回答,但古挪威人在格陵兰和美洲殖民失败的终极原因是非常清楚的。它的失败是由于发起者(挪威)、目标(格陵兰和纽芬兰)和时间(公元984—1410年)必然使欧洲在粮食生产、技术和政治组织方面的潜在优势无法得到有效的运用。在对很大一部分粮食生产都不相宜的纬度太高的地区,在欧洲穷国之一的无力支持下,几个古挪威人手中的铁器没有斗得过爱斯基摩人和印第安狩猎采集族群手中的石器、骨器和木器,要知道这后两种人是世界上掌握在北极地区生存技巧的最伟大的专家!

THE SECOND EURASIAN attempt to colonize the Americas succeeded because it involved a source, target, latitude, and time that allowed Europe's potential advantages to be exerted effectively. Spain, unlike Norway, was rich and populous enough to support exploration and subsidize colonies. Spanish landfalls in the Americas were at subtropical latitudes highly suitable for food production, based at first mostly on Native American crops but also on Eurasian domestic animals, especially cattle and horses. Spain's transatlantic colonial enterprise began in 1492, at the end of a century of rapid development of European oceangoing ship technology, which by then incorporated advances in navigation, sails, and ship design developed by Old World societies (Islam, India, China, and Indonesia) in the Indian Ocean. As a result, ships built and manned in Spain itself were able to sail to the West Indies; there was nothing equivalent to the Greenland bottleneck that had throttled Norse colonization. Spain's New World colonies were soon joined by those of half a dozen other European states.

欧亚大陆人第二次向美洲移民的企图成功了,因为这一次在发起者、目标、纬度和时间方面都使欧洲的潜在优势得以有效地发挥。和挪威不同,西班牙富有而又人口众多,足以支持海外探险和对殖民地进行资助。西班牙人在美洲的登陆处的纬度是非常适于粮食生产的亚热带地区,那里粮食生产的基础起先主要是印第安的作物,但也有欧亚大陆的家畜,特别是牛和马。西班牙横渡大西洋的雄心勃勃的殖民事业开始于1492年,这时欧洲远洋船只建造技术为时达一个世纪的迅速发展宣告结束,它吸收了旧大陆社会(伊斯兰世界、印度、中国和印度尼西亚)在印度洋发展起来的先进的航海术、风帆和船舶设计。在西班牙建造和配备人员的船只能够航行到西印度群岛;类似于格陵兰岛上妨碍古挪威人殖民的那种情况不复存在了。西班牙在新大陆建立了殖民地之后,很快又有6、7个欧洲国家加入到开拓殖民地的行列中来。

The first European settlements in the Americas, beginning with the one founded by Columbus in 1492, were in the West Indies. The island Indians, whose estimated population at the time of their “discovery” exceeded a million, were rapidly exterminated on most islands by disease, dispossession, enslavement, warfare, and casual murder. Around 1508 the first colony was founded on the American mainland, at the Isthmus of Panama. Conquest of the two large mainland empires, those of the Aztecs and Incas, followed in 1519–1520 and 1532–1533, respectively. In both conquests European-transmitted epidemics (probably smallpox) made major contributions, by killing the emperors themselves, as well as a large fraction of the population. The overwhelming military superiority of even tiny numbers of mounted Spaniards, together with their political skills at exploiting divisions within the native population, did the rest. European conquest of the remaining native states of Central America and northern South America followed during the 16th and 17th centuries.

欧洲在美洲的第一批殖民地在西印度群岛,以哥伦布于1492年建立的殖民地为其开端。西印度群岛的印第安人在他们被“发现”时估计人口超过100万,但大多数岛上的印第安人很快就被疾病、驱逐、奴役、战争和随便杀害消灭了。1508年左右,美洲大陆上的第一个殖民地在巴拿马地峡建立。随后分别在1519-1520年和1532-1533年发生了对美洲大陆上两个大帝国阿兹特克帝国和印加帝国的征服。在这两次征服中,欧洲人传播的流行病(可能是天花)起了主要的作用,不但杀死了大批人口,而且还杀死了皇帝本人。其余的事则是由一小撮西班牙骑兵在军事上的压倒优势和他们利用当地人口的内部分歧的政治技巧来完成的。在16世纪和17世纪中,接着又发生了欧洲人对中美洲和南美洲北部其余土邦的征服。

As for the most advanced native societies of North America, those of the U.S. Southeast and the Mississippi River system, their destruction was accomplished largely by germs alone, introduced by early European explorers and advancing ahead of them. As Europeans spread throughout the Americas, many other native societies, such as the Mandans of the Great Plains and the Sadlermiut Eskimos of the Arctic, were also wiped out by disease, without need for military action. Populous native societies not thereby eliminated were destroyed in the same way the Aztecs and Incas had been—by full-scale wars, increasingly waged by professional European soldiers and their native allies. Those soldiers were backed by the political organizations initially of the European mother countries, then of the European colonial governments in the New World, and finally of the independent neo-European states that succeeded the colonial governments.

至于北美洲的那些最先进的土著社会,即美国东南部和密西西比河水系地区的社会,它们的毁灭主要是由病菌独立完成的,病菌由早期的欧洲探险者带来,但却走在他们的前面。随着欧洲人的足迹踏遍美洲,其他许多土著社会,如大平原的曼丹人社会和北极地区的萨德勒缪特爱斯基摩人社会,也是不用军事行动就被疾病消灭了。没有被疾病消灭的人口众多的土著社会,则遭到了与阿兹特克人和印加人的同样命运,被一些全面的战争摧毁了,发动战争的越来越多的是欧洲职业军人和他们在当地的盟友。作为这些军人的后盾的,先是欧洲母国的政治组织,后来是新大陆的欧洲殖民地政府,最后是继承殖民地政府的独立的新兴欧洲国家。

Smaller native societies were destroyed more casually, by small-scale raids and murders carried out by private citizens. For instance, California's native hunter-gatherers initially numbered about 200,000 in aggregate, but they were splintered among a hundred tribelets, none of which required a war to be defeated. Most of those tribelets were killed off or dispossessed during or soon after the California gold rush of 1848–52, when large numbers of immigrants flooded the state. As one example, the Yahi tribelet of northern California, numbering about 2,000 and lacking firearms, was destroyed in four raids by armed white settlers: a dawn raid on a Yahi village carried out by 17 settlers on August 6, 1865; a massacre of Yahis surprised in a ravine in 1866; a massacre of 33 Yahis tracked to a cave around 1867; and a final massacre of about 30 Yahis trapped in another cave by 4 cowboys around 1868. Many Amazonian Indian groups were similarly eliminated by private settlers during the rubber boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The final stages of the conquest are being played out in the present decade, as the Yanomamo and other Amazonian Indian societies that remain independent are succumbing to disease, being murdered by miners, or being brought under control by missionaries or government agencies.

较小的土著社会则被私人组织的小规模的袭击和屠杀更随便地消灭了。例如,加利福尼亚的土著狩猎采集族群起初总共有20万人,但他们分散在100个小部落中,要打败其中任何一个小部落根本用不着战争。在1842—1852年的加利福尼亚淘金热期间或其后不久,大多数这样的小部落被杀光的杀光,被赶走的赶走,同时大批的移民涌入了该州。举一个例子,加利福尼亚北部的亚希小部落,人数在2000左右,也没有火器。他们被武装的白人移民的4次袭击消灭了:一次是1865年8月6日17个移民在黎明时对一个亚希人的村庄发动的袭击;一次是1866年在一个深谷中对亚希人出其不意的屠杀;一次是1867年左右跟踪到一处洞穴对33个亚希人的屠杀;最后一次是1868年左右对被4个牛仔诱进另一个洞穴的大约30个亚希人的屠杀。在19世纪末20世纪初的割胶热中,亚马孙河地区的许多印第安群体被白人移民用同样的方式消灭了。这种征服的最后几出戏是在当前的这10年中演完的,如始终独立的雅诺马马人社会和亚马孙河地区其他的印第安人社会,或是死于疾病,或是被矿工杀害,或是被置于传教士和政府机构的控制之下。

The end result has been the elimination of populous Native American societies from most temperate areas suitable for European food production and physiology. In North America those that survived as sizable intact communities now live mostly on reservations or other lands considered undesirable for European food production and mining, such as the Arctic and arid areas of the U.S. West. Native Americans in many tropical areas have been replaced by immigrants from the Old World tropics (especially black Africans, along with Asian Indians and Javanese in Suriname).

最终结果是:在适合欧洲的粮食生产和欧洲人生理机能的气候最温和的地区,人口众多的印第安社会被消灭了。在北美洲,相当大的保存下来的完整社会,现在多半生活在居留地里或其他一些被认为不适于欧洲的粮食生产和采矿的地方,如北极地区和美国西部的贫瘠地区。许多热带地区的印第安人已被来自旧大陆热带地区的移民所取代(尤其是非洲黑人以及亚洲的印度人和苏里南的爪哇人)。

In parts of Central America and the Andes, the Native Americans were originally so numerous that, even after epidemics and wars, much of the population today remains Native American or mixed. That is especially true at high altitudes in the Andes, where genetically European women have physiological difficulties even in reproducing, and where native Andean crops still offer the most suitable basis for food production. However, even where Native Americans do survive, there has been extensive replacement of their culture and languages with those of the Old World. Of the hundreds of Native American languages originally spoken in North America, all except 187 are no longer spoken at all, and 149 of these last 187 are moribund in the sense that they are being spoken only by old people and no longer learned by children. Of the approximately 40 New World nations, all now have an Indo-European language or creole as the official language. Even in the countries with the largest surviving Native American populations, such as Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, and Guatemala, a glance at photographs of political and business leaders shows that they are disproportionately Europeans, while several Caribbean nations have black African leaders and Guyana has had Asian Indian leaders.

在中美洲和安第斯山脉的一些地区,印第安人本来人数很多,即使在流行病和战争之后,人口中的很大一部分今天仍然是印第安人或混血人。在安第斯山脉的高纬度地区情况尤其如此,那里的欧洲妇女甚至在生育方面也有遗传性的生理障碍,那里的安第斯山脉本地的作物仍是粮食生产的最合适的基础。然而,即使在印第安人生存的地方,他们的文化和语言也已被旧大陆的文化和语言所取代了。原先在北美洲使用的几百种印第安语言,除187种外,全都不再使用,而就是在这最后的187种语言中,也有149种奄奄一息,就是说只有老人还在使用,儿童已不再学了。在大概40个新大陆国家中,现在全都把某种印欧语或克里奥耳语[1]作为官方语言。甚至在那些现存印第安人口最多的国家中,如秘鲁、玻利维亚、墨西哥和危地马拉,只要看一看政界和商界领袖的照片,就可以看出,他们很多都是欧洲人,而几个加勒比海国家的领袖是非洲黑人,圭亚那的领导人则是印度人。

The original Native American population has been reduced by a debated large percentage: estimates for North America range up to 95 percent. But the total human population of the Americas is now approximately ten times what it was in 1492, because of arrivals of Old World peoples (Europeans, Africans, and Asians). The Americas' population now consists of a mixture of peoples originating from all continents except Australia. That demographic shift of the last 500 years—the most massive shift on any continent except Australia—has its ultimate roots in developments between about 11,000 B.C. and A.D. 1.

原来的印第安人口已经减少了,至于减少了多少,则是一个有争论的问题:据估计在北美洲最高可达95%。但由于旧大陆的人(欧洲人、非洲人和亚洲人)的到来,现在美洲的总人口大概是1492年的10倍。现在美洲的人口是来自除澳大利亚外所有大陆的人们的混合体。这种在过去500年中发生的人口变迁——除澳大利亚外任何大陆上最大的人口变迁——的最早的根子,在大约公元前1100年和公元元年之间的各个发展阶段中就已种下了。

注释:

1. 克里奥耳语:如美国路易斯安那人和海地人讲的法语方言。——译者