CHAPTER 19

第十九章

HOW AFRICA BECAME BLACK

非洲是怎样成为黑人的非洲的

NO MATTER HOW MUCH ONE HAS READ ABOUT AFRICA beforehand, one's first impressions from actually being there are overwhelming. On the streets of Windhoek, capital of newly independent Namibia, I saw black Herero people, black Ovambos, whites, and Namas, different again from both blacks and whites. They were no longer mere pictures in a textbook, but living humans in front of me. Outside Windhoek, the last of the formerly widespread Kalahari Bushmen were struggling for survival. But what most surprised me in Namibia was a street sign: one of downtown Windhoek's main roads was called Goering Street!

不管你事前读过多少关于非洲的书,一旦你身临其境,你对那里的第一个印象使你感到不知所措。在新独立的纳米比亚的首都温得和克的街道上,我看到了赫雷罗族黑人、奥万博族黑人、白人和既不同于黑人也不同于白人的纳马族人。他们不再是教科书里照片上的人物,而是我眼前的活生生的人。在温得和克外面,过去分布很广的卡拉哈里沙漠布须曼人现在只剩下最后一批了,他们正在为生存而奋斗。但在纳米比亚最使我感到惊讶的是一个街的名字:温得和克闹市区的主要马路之一竟叫做“戈林街”!

Surely, I thought, no country could be so dominated by unrepentant Nazis as to name a street after the notorious Nazi Reichskommissar and founder of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering! No, it turned out that the street instead commemorated Hermann's father, Heinrich Goering, founding Reichskommissar of the former German colony of South-West Africa, which became Namibia. But Heinrich was also a problematic figure, for his legacy included one of the most vicious attacks by European colonists on Africans, Germany's 1904 war of extermination against the Hereros. Today, while events in neighboring South Africa command more of the world's attention, Namibia as well is struggling to deal with its colonial past and establish a multiracial society. Namibia illustrated for me how inseparable Africa's past is from its present.

我本来以为,肯定不会有哪个国家受到不知悔改的纳粹分子那么大的影响,竟然会用那臭名昭著的纳粹德国国会议员、纳粹德国空军的创建者赫尔曼·戈林的名字来给一条街道命名!果然如此。原来这条街是为纪念赫尔曼的父亲亨利希·戈林而命名的。亨利希·戈林是前德国殖民地西南非洲(后来成为纳米比亚)的帝国议会创始人。但亨利希也是一个有问题的人物,因为他的业绩包括欧洲殖民者对非洲人的一次最凶残的袭击,即德国于1904年对赫雷罗人发动的种族灭绝的战争。今天,虽然邻国南非的事态发展受到全世界较多的关注,但纳米比亚也在努力克服过去殖民地的影响并建立一个多种族和睦相处的社会。纳米比亚向我证明了非洲的过去和现在是多么地难分难解。

Most Americans and many Europeans equate native Africans with blacks, white Africans with recent intruders, and African racial history with the story of European colonialism and slave trading. There is an obvious reason why we focus on those particular facts: blacks are the sole native Africans familiar to most Americans, because they were brought in large numbers as slaves to the United States. But very different peoples may have occupied much of modern black Africa until as recently as a few thousand years ago, and so-called African blacks themselves are heterogeneous. Even before the arrival of white colonialists, Africa already harbored not just blacks but (as we shall see) five of the world's six major divisions of humanity, and three of them are confined as natives to Africa. One-quarter of the world's languages are spoken only in Africa. No other continent approaches this human diversity.

大多数美国人和许多欧洲人把非洲的土著看作就是黑人,非洲的白人就是近代的入侵者,非洲的种族历史就是欧洲殖民主义和奴隶贸易的历史。我们之所以只注意这些特有的事实,有一个显而易见的原因:黑人是大多数美国人所熟悉的唯一的非洲土著居民,因为他们曾经大批地作为奴隶被运来美国。但是直到几千年前,现代黑非洲的很大一部分地区还可能为一些完全不同的民族所占有,而所谓非洲黑人其本身也是来源各异的。甚至在白人殖民主义者来到之前,已经生活在非洲的不只是黑人,而是(我们将要看到)世界上6大人种中有5个生活在非洲,其中3个只生活在非洲。世界上的语言,有四分之一仅仅在非洲才有人说。没有哪一个大陆在人种的多样性方面可以与非洲相提并论。

Africa's diverse peoples resulted from its diverse geography and its long prehistory. Africa is the only continent to extend from the northern to the southern temperate zone, while also encompassing some of the world's driest deserts, largest tropical rain forests, and highest equatorial mountains. Humans have lived in Africa far longer than anywhere else: our remote ancestors originated there around 7 million years ago, and anatomically modern Homo sapiens may have arisen there since then. The long interactions between Africa's many peoples generated its fascinating prehistory, including two of the most dramatic population movements of the past 5,000 years—the Bantu expansion and the Indonesian colonization of Madagascar. All of those past interactions continue to have heavy consequences, because the details of who arrived where before whom are shaping Africa today.

非洲多样化的人种来自它的多样化的地理条件和悠久的史前史。非洲是唯一的地跨南北温带的大陆,同时它也有一些世界上最大的沙漠、最大的热带雨林和最高的赤道山脉。人类在非洲生活的时间比在任何其他地方都要长得多:我们的远祖大约在700万年前发源于非洲,解剖学上的现代智人可能是在那以后在非洲出现的。非洲许多民族之间长期以来的相互作用,产生了令人着迷的史前史,包括过去5000年中两次最引人注目的人口大迁移——班图人的扩张和印度尼西亚人向马达加斯加的移民。所有过去的这些相互作用在继续产生巨大的影响,因为谁在谁之前到达了那里之类问题的细节塑造了今天的非洲。

How did those five divisions of humanity get to be where they are now in Africa? Why were blacks the ones who came to be so widespread, rather than the four other groups whose existence Americans tend to forget? How can we ever hope to wrest the answers to those questions from Africa's preliterate past, lacking the written evidence that teaches us about the spread of the Roman Empire? African prehistory is a puzzle on a grand scale, still only partly solved. As it turns out, the story has some little-appreciated but striking parallels with the American prehistory that we encountered in the preceding chapter.

那5个人种是怎样到达他们如今在非洲所在的地方的呢?为什么在非洲分布最广的竟是黑人,而不是美国人往往忘记其存在的其他4个群体?非洲过去的历史是没有文字的历史,它没有那种把罗马帝国扩张情况说给我们听的文字证据。那么,我们又怎样才能指望从它的过去历史中努力得到对这些问题的答案。非洲的史前史是一个大大的谜团,仍然只是部分地得到解答。结果证明,非洲的情况同我们在前一章中所讨论的美洲史前史有着某种惊人的类似之处,不过很少得到重视罢了。

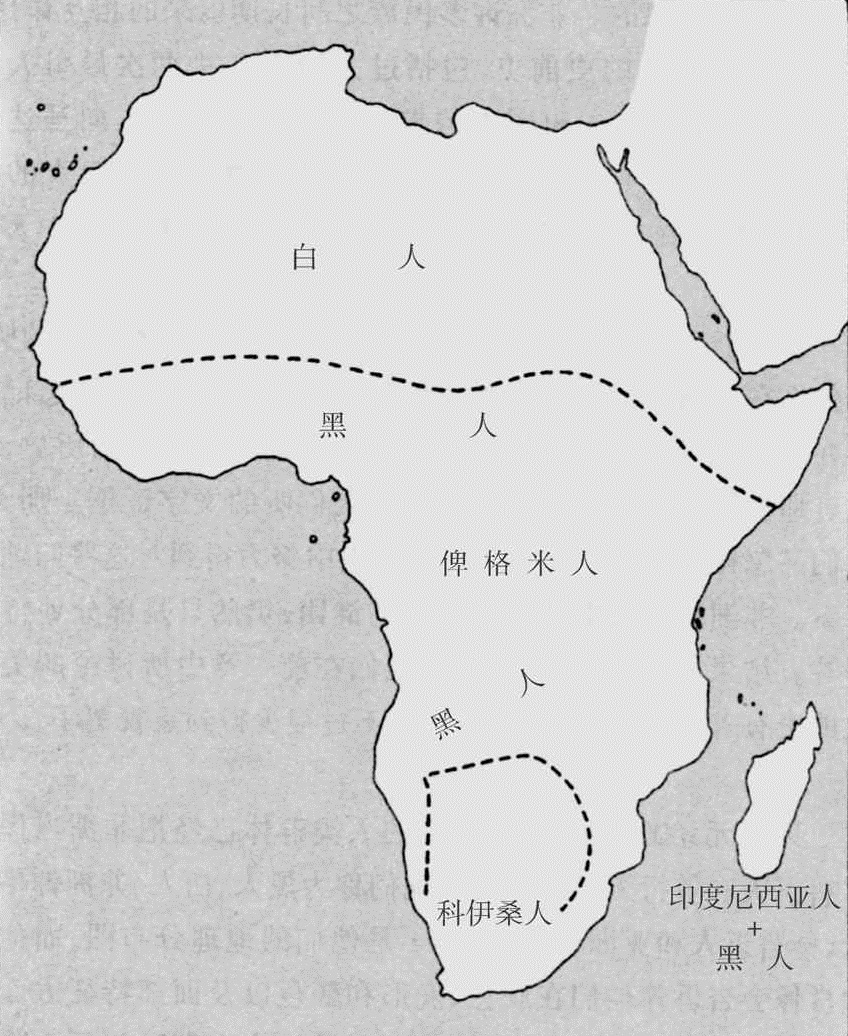

THE FIVE MAJOR human groups to which Africa was already home by A.D. 1000 are those loosely referred to by laypeople as blacks, whites, African Pygmies, Khoisan, and Asians. Figure 19.1 depicts their distributions, while the portraits following Chapter 19 will remind you of their striking differences in skin color, hair form and color, and facial features. Blacks were formerly confined to Africa, Pygmies and Khoisan still live only there, while many more whites and Asians live outside Africa than in it. These five groups constitute or represent all the major divisions of humanity except for Aboriginal Australians and their relatives.

到公元1000年,这5个主要的人类群体已经把非洲当作自己的家园。外行人不严密地把他们称为黑人、白人、非洲俾格米人、科伊桑人和亚洲人。图19.1是他们的地理分布图,而他们的肖像会告诉你他们在肤色、发形和颜色以及面部特征方面的明显差异。黑人以前只生活在非洲,俾格米人和科伊桑人现在仍然生活在非洲,而白人和亚洲人生活在非洲之外的比生活在非洲之内的多得多。这5个群体构成了或代表了除澳大利亚土著及其亲戚外的全部主要的人种。

非洲民族分布图(到公元1400年止)

19.1. See the text for caveats about describing distributions of Afric peoples in terms of these familiar but problematical groupings.

图19.1关于用这些大家熟悉的然而有问题的分类法介绍的非洲民族的地理分布,为防止误解而作的解释,参见正文。

Many readers may already be protesting: don't stereotype people by classifying them into arbitrary “races”! Yes, I acknowledge that each of these so-called major groups is very diverse. To lump people as different as Zulus, Somalis, and Ibos under the single heading of “blacks” ignores the differences between them. We ignore equally big differences when we lump Africa's Egyptians and Berbers with each other and with Europe's Swedes under the single heading of “whites.” In addition, the divisions between blacks, whites, and the other major groups are arbitrary, because each such group shades into others: all human groups on Earth have mated with humans of every other group that they encountered. Nevertheless, as we'll see, recognizing these major groups is still so useful for understanding history that I'll use the group names as shorthand, without repeating the above caveats in every sentence.

许多读者可能已在表示抗议了:不要用随意划分“人种”的办法把人定型!是的,我承认,每一个所谓的这样的主要群体是十分多样化的。把祖鲁人、索马里人和伊博人这样不同的人归并在“黑人”这一个类目下,是无视他们之间的差异。如果我们把非洲的埃及人和柏柏尔人以及欧洲的瑞典人一起归并在“白人”这一个类目下,我们同样是无视他们之间的巨大差异。此外,黑人、白人和其他主要群体这种划分是随意的,因为每一个这样的群体和其他群体的界限很难分得清楚:地球上所有人类群体只要和其他每一个群体中的人接触,就会发生婚配关系。不过,我们将会看到,承认这些主要的群体对了解历史仍然十分有用,我们可以把这些群体的名称当作一种简略的表达方法,而不用每句话都重复一下上面为防止误解而作的解释。

Of the five African groups, representatives of many populations of blacks and whites are familiar to Americans and Europeans and need no physical description. Blacks occupied the largest area of Africa even as of A.D. 1400: the southern Sahara and most of sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 19.1). While American blacks of African descent originated mainly from Africa's west coastal zone, similar peoples traditionally occupied East Africa as well, north to the Sudan and south to the southeast coast of South Africa itself. Whites, ranging from Egyptians and Libyans to Moroccans, occupied Africa's north coastal zone and the northern Sahara. Those North Africans would hardly be confused with blue-eyed blond-haired Swedes, but most laypeople would still call them “whites” because they have lighter skin and straighter hair than peoples to the south termed “blacks.” Most of Africa's blacks and whites depended on farming or herding, or both, for their living.

在非洲的这5个群体中,许多黑人和白人的典型代表是美国人和欧洲人所熟悉的,不需要对他们的体形特征加以描写。甚至到公元1400年止,黑人仍然占据着非洲最大的地区:撒哈拉沙漠的南部和撒哈拉沙漠以南非洲的大部分地区(见图19.1)。虽然美洲的非裔黑人后代主要源自非洲西海岸带,但同样的民族在传统上还占据了东非地区,北达苏丹,南至南非的东南海岸。包括埃及人、利比亚人和摩洛哥人的白人占据了非洲的北海岸带和撒哈拉沙漠的北部。这些北非人几乎不可能与蓝眼金发的瑞典人混同起来,但大多数外行人仍然会把他们称为“白人”,因为同南面的叫做“黑人”的人相比,他们的肤色较浅,头发较直。大多数非洲的黑人和白人靠种田或放牧或两者维持生计。

In contrast, the next two groups, the Pygmies and Khoisan, include hunter-gatherers without crops or livestock. Like blacks, Pygmies have dark skins and tightly curled hair. However, Pygmies differ from blacks in their much smaller size, more reddish and less black skins, more extensive facial and body hair, and more prominent foreheads, eyes, and teeth. Pygmies are mostly hunter-gatherers living in groups widely scattered through the Central African rain forest and trading with (or working for) neighboring black farmers.

相比之下,其次两个群体——俾格米人和科伊桑人则包括没有作物和牲畜的狩猎采集族群。俾格米人和黑人一样,生有深色皮肤和浓密的鬈发。然而,俾格米人身材矮小得多,皮肤微红色较多,黑色的较少,脸上和身体上的毛较多,以及前额、眼睛和牙齿较突出——这些都是和黑人不同的地方。俾格米人大都过着群体的狩猎采集生活,他们的群体广泛分布在中非的雨林中,与邻近的黑人农民进行交换(或为他们干活)。

The Khoisan make up the group least familiar to Americans, who are unlikely even to have heard of their name. Formerly distributed over much of southern Africa, they consisted not only of small-sized hunter-gatherers, known as San, but also of larger herders, known as Khoi. (These names are now preferred to the better-known terms Hottentot and Bushmen.) Both the Khoi and the San look (or looked) quite unlike African blacks: their skins are yellowish, their hair is very tightly coiled, and the women tend to accumulate much fat in their buttocks (termed “steatopygia”). As a distinct group, the Khoi have been greatly reduced in numbers: European colonists shot, displaced, or infected many of them, and most of the survivors interbred with Europeans to produce the populations variously known in South Africa as Coloreds or Basters. The San were similarly shot, displaced, and infected, but a dwindling small number have preserved their distinctness in Namibian desert areas unsuitable for agriculture, as depicted some years ago in the widely seen film The Gods Must Be Crazy.

科伊桑人的群体是美国人最不熟悉的,美国人可能连他们的名字都没有听说过。他们以前分布在非洲南部的广大地区,他们中不但有叫做桑人的人数不多的狩猎采集者,而且还有叫做科伊人的人数较多的牧人。(现在人们更喜欢用那比较熟悉的名字霍屯督人和布须曼人。)科伊人和桑人看上去(或曾经看上去)与非洲黑人很不相同:他们的皮肤微黄,他们的头发十分浓密而卷曲,妇女往往在臀部积累了大量的脂肪(医学上称为“臀脂过多”)。作为一个与众不同的群体,科伊人的人数已经大大减少了,因为欧洲殖民者枪杀、驱赶和用疾病感染了他们许多人,大多数幸存者和欧洲人生下了混血种,这些混血人口在南美有时叫混血人,有时叫巴斯特人。桑人同样地受到枪杀、驱赶和疾病的感染,但在不适于农业的纳米比亚沙漠地区,有一批人数日渐减少的桑人仍然保持着他们的特色,若干年前有一部吸引很多观众的影片《诸神该是疯了》描写的就是他们这些人。

The northern distribution of Africa's whites is unsurprising, because physically similar peoples live in adjacent areas of the Near East and Europe. Throughout recorded history, people have been moving back and forth between Europe, the Near East, and North Africa. I'll therefore say little more about Africa's whites in this chapter, since their origins aren't mysterious. Instead, the mystery involves blacks, Pygmies, and Khoisan, whose distributions hint at past population upheavals. For instance, the present fragmented distribution of the 200,000 Pygmies, scattered amid 120 million blacks, suggests that Pygmy hunters were formerly widespread through the equatorial forests until displaced and isolated by the arrival of black farmers. The Khoisan area of southern Africa is surprisingly small for a people so distinct in anatomy and language. Could the Khoisan, too, have been originally more widespread until their more northerly populations were somehow eliminated?

非洲白人分布在非洲北部,这是没有什么奇怪的,因为体质相似的民族都生活在近东和欧洲的邻近地区。有史以来,人们一直在欧洲、近东和北非之间来来往往。因此,在本章中对非洲白人我不会作过多的讨论,因为他们的来源并无任何神秘之处。神秘的倒是黑人、俾格米人和科伊桑人,因为他们的地理分布暗示了过去人口的激烈变动。例如,现在零星分布的20万俾格米人散居在1.2亿黑人中间,这就表明俾格米猎人以前曾遍布赤道森林,后来由于黑人农民的到来,他们才被赶走和隔离开来。科伊桑人在解剖学上和语言上都是一个十分独特的民族,但他们在非洲南部所拥有的地区却小得令人吃惊。会不会科伊桑人本来也分布较广,后来他们在北面的人口由于某种原因而被消灭了?

I've saved the biggest anomaly for last. The large island of Madagascar lies only 250 miles off the East African coast, much closer to Africa than to any other continent, and separated by the whole expanse of the Indian Ocean from Asia and Australia. Madagascar's people prove to be a mixture of two elements. Not surprisingly, one element is African blacks, but the other consists of people instantly recognizable, from their appearance, as tropical Southeast Asians. Specifically, the language spoken by all the people of Madagascar—Asians, blacks, and mixed—is Austronesian and very similar to the Ma'anyan language spoken on the Indonesian island of Borneo, over 4,000 miles across the open Indian Ocean from Madagascar. No other people remotely resembling Borneans live within thousands of miles of Madagascar.

我已把这个最大的异常现象留到最后来讨论。马达加斯加这个大岛在东非海岸外只有250英里,它离非洲大陆比离任何其他大陆都近得多,它与亚洲及澳大利亚之间隔着印度洋的广阔水域。马达加斯加岛上的人是两种成分的混合。一个成分是非洲黑人,这是意料之中的事,但另一个成分从外貌上一眼就可看出是热带东南亚人。特别是,所有马达加斯加人——亚洲人、黑人和混血人——所说的语言是南岛语,与印度尼西亚婆罗洲岛上说的马安亚语非常相似,而婆罗洲与马达加斯加隔着开阔的印度洋有4000多英里远。没有任何一个哪怕与婆罗洲人有一点点相似的民族是生活在马达加斯加的几千英里范围之内的。

These Austronesians, with their Austronesian language and modified Austronesian culture, were already established on Madagascar by the time it was first visited by Europeans, in 1500. This strikes me as the single most astonishing fact of human geography for the entire world. It's as if Columbus, on reaching Cuba, had found it occupied by blue-eyed, blond-haired Scandinavians speaking a language close to Swedish, even though the nearby North American continent was inhabited by Native Americans speaking Amerindian languages. How on earth could prehistoric people of Borneo, presumably voyaging in boats without maps or compasses, end up in Madagascar?

当欧洲人于1500年第一次访问马达加斯加时,那些说南岛语的人带着他们的南岛语和经过改造的南岛文化已经在那里扎下根来。我认为,这是全世界人类地理学上的一个最令人惊异的事实。这就好像哥伦布在到达古巴时发现岛上的居民竟是蓝眼金发、说着一种类似瑞典语的语言的北欧人,尽管附近的北美大陆居住着说美洲印第安语的印第安人。据推测,史前的婆罗洲人在没有地图和罗盘的情况下乘船航行,最后到了马达加斯加。他们究竟是怎样做到这一点的呢?

THE CASE OF Madagascar tells us that peoples' languages, as well as their physical appearance, can yield important clues to their origins. Just by looking at the people of Madagascar, we'd have known that some of them came from tropical Southeast Asia, but we wouldn't have known from which area of tropical Southeast Asia, and we'd never have guessed Borneo. What else can we learn from African languages that we didn't already know from African faces?

马达加斯加的这个例子告诉我们,民族的语言同他们的体形外貌一样,能够提供关于他们的起源的重要线索。只要看一看马达加斯加岛上的人,我们就会知道他们中有些人源自热带东南亚,但我们不可能知道是热带东南亚的哪个地区,而且我们绝不会猜到是婆罗洲。我们从非洲语言还能知道哪些我们不能从非洲人面相上知道的东西?

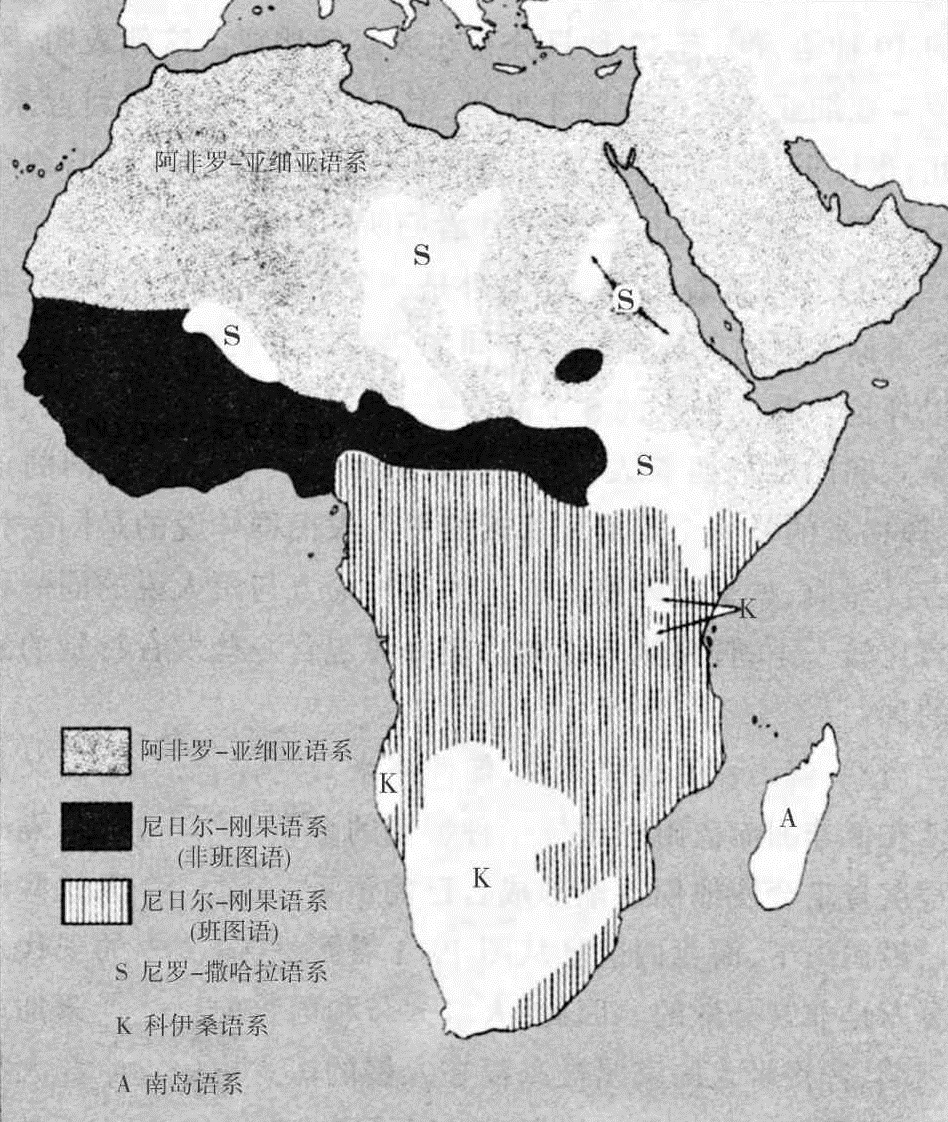

The mind-boggling complexities of Africa's 1,500 languages were clarified by Stanford University's great linguist Joseph Greenberg, who recognized that all those languages fall into just five families (see Figure 19.2 for their distribution). Readers accustomed to thinking of linguistics as dull and technical may be surprised to learn what fascinating contributions Figure 19.2 makes to our understanding of African history.

非洲有1500种语言,复杂得令人难以想象。斯坦福大学的大语言学家约瑟夫·格林伯格把它们加以梳理,使之变得清晰明了。他确认,所有这些语言正好分为5个语系(它们的地理分布见图19.2)。读者们习惯上认为语言学枯燥乏味而过于专门,但如果他们知道图19.2对于我们了解非洲的历史作出了什么样的有趣贡献,他们也许会感到惊奇。

Figure 19.2. Language families of Africa.

图19.2 非洲诸语系[1]

If we begin by comparing Figure 19.2 with Figure 19.1, we'll see a rough correspondence between language families and anatomically defined human groups: languages of a given language family tend to be spoken by distinct people. In particular, Afroasiatic speakers mostly prove to be people who would be classified as whites or blacks, Nilo-Saharan and Niger-Congo speakers prove to be blacks, Khoisan speakers Khoisan, and Austronesian speakers Indonesian. This suggests that languages have tended to evolve along with the people who speak them.

如果我们首先把图19.2和图19.1比较一下,我们就会看到,语系和解剖学上界定的人类群体之间有着一种大致的对应关系:某个语系中的语言往往是由不同的人说的。特别是,说阿非罗-亚细亚语言的人多半证明是可以被归为白人或黑人一类的人,说尼罗-撒哈拉语和尼日尔-刚果语的人证明是黑人,说科伊桑语的是科伊桑人,说南岛语的是印度尼西亚人。这表明语言往往是和说这些语言的人一起演化的。

Concealed at the top of Figure 19.2 is our first surprise, a big shock for Eurocentric believers in the superiority of so-called Western civilization. We're taught that Western civilization originated in the Near East, was brought to brilliant heights in Europe by the Greeks and Romans, and produced three of the world's great religions: Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Those religions arose among peoples speaking three closely related languages, termed Semitic languages: Aramaic (the language of Christ and the Apostles), Hebrew, and Arabic, respectively. We instinctively associate Semitic peoples with the Near East.

在图19.2的上方隐藏着我们的第一个意外,对那些相信所谓西方文明的优越性的欧洲中心论者也是一个巨大的打击。人们教导我们说,西方文明起源于近东,被希腊人和罗马人在欧洲发展到光辉的顶峰,并产生了世界上的3大宗教:基督教、犹太教和伊斯兰教。这些宗教发生在说3种叫做闪语的近亲语言的人们当中,这3种语言分别是阿拉米语(基督和使徒的语言)、希伯来语和阿拉伯语。我们本能地把闪语民族和近东联系在一起。

However, Greenberg determined that Semitic languages really form only one of six or more branches of a much larger language family, Afroasiatic, all of whose other branches (and other 222 surviving languages) are confined to Africa. Even the Semitic subfamily itself is mainly African, 12 of its 19 surviving languages being confined to Ethiopia. This suggests that Afroasiatic languages arose in Africa, and that only one branch of them spread to the Near East. Hence it may have been Africa that gave birth to the languages spoken by the authors of the Old and New Testaments and the Koran, the moral pillars of Western civilization.

然而,格林伯格断定,闪语实际上只形成了一个大得多的语系——阿非罗-亚细亚语系中6个或更多分支语言中的一支,阿非罗-亚细亚语系的所有其他分支(和现存的其他222种语言)只分布在非洲。甚至闪语族本身也主要是非洲语言,它的现存的19种语言中有12种只分布在埃塞俄比亚。这就表明,阿非罗-亚细亚诸语言起源于非洲,其中只有一支传播到近东。因此,也许正是非洲产生了作为西方文明道德支柱的《旧约全书》、《新约全书》和《古兰经》的作者们所使用的语言。

The next surprise in Figure 19.2 is a seeming detail on which I didn't comment when I just told you that distinct peoples tend to have distinct languages. Among Africa's five groups of people—blacks, whites, Pygmies, Khoisan, and Indonesians—only the Pygmies lack any distinct languages: each band of Pygmies speaks the same language as the neighboring group of black farmers. However, if one compares a given language as spoken by Pygmies with the same language as spoken by blacks, the Pygmy version seems to contain some unique words with distinctive sounds.

图19.2隐藏着的下一个意外是一个表面上的细节,刚才我在告诉你不同的民族往往有不同的语言时并没有对这个细节加以评论。在非洲人的5个群体——黑人、白人、俾格米人、科伊桑人和印度尼西亚人中,只有俾格米人没有任何不同的语言:俾格米的每一个族群和邻近的黑人农民群体说的是同一种语言。然而,如果把俾格米人说的某种语言与黑人说的同一种语言比较一下,俾格米人说的话里好像包含一些发音特别的独特的词。

Originally, of course, people as distinctive as the Pygmies, living in a place as distinctive as the equatorial African rain forest, were surely isolated enough to develop their own language family. However, today those languages are gone, and we already saw from Figure 19.1 that the Pygmies' modern distribution is highly fragmented. Thus, distributional and linguistic clues combine to suggest that the Pygmy homeland was engulfed by invading black farmers, whose languages the remaining Pygmies adopted, leaving only traces of their original languages in some words and sounds. We saw previously that much the same is true of the Malaysian Negritos (Semang) and Philippine Negritos, who adopted Austroasiatic and Austronesian languages, respectively, from the farmers who came to surround them.

当然,就语言的起源来说,像俾格米人这样特别的人,又是生活在像非洲赤道雨林这样一种特别的地方,他们的与世隔绝的程度肯定会使他们逐渐形成自己的语系。然而,今天这些语言已经消失了,而我们也已从图19.1看到,俾格米人的现代地理分布是非常分散的。因此,人口分布和语言方面的线索加起来表明,俾格米人的家园被淹没在入侵的黑人农民的汪洋大海之中,硕果仅存的一些俾格米人采用了这些农民的语言,而他们原来的语言只在某些词和发音上留下了一些蛛丝马迹。我们在前面已经看到,马来西亚的矮小黑人(塞芒人)和菲律宾的矮小黑人的情况也基本如此,他们从包围了他们的农民那里分别采用了南亚语和南岛语。

The fragmented distribution of Nilo-Saharan languages in Figure 19.2 similarly implies that many speakers of those languages have been engulfed by speakers of Afroasiatic or Niger-Congo languages. But the distribution of Khoisan languages testifies to an even more dramatic engulfing. Those languages are famously unique in the whole world in their use of clicks as consonants. (If you've been puzzled by the name !Kung Bushman, the exclamation mark is not an expression of premature astonishment; it's just how linguists denote a click.) All existing Khoisan languages are confined to southern Africa, with two exceptions. Those exceptions are two very distinctive, click-laden Khoisan languages named Hadza and Sandawe, stranded in Tanzania more than 1,000 miles from the nearest Khoisan languages of southern Africa.

图19.2中尼罗-撒哈拉诸语言的零星分散的分布同样表明了,许多说这些语言的人也被淹没在说阿非罗-亚细亚语言和说尼日尔-刚果语的人的汪洋大海之中。但科伊桑语言的分布说明了一种甚至更加引人注目的“淹没”现象。这些语言用吸气音作辅音,这在全世界是非常独特的。(如果你对 !库恩·布什曼这个名字感到莫名其妙,那么这个惊叹号不是表示一个过早的惊愕,它只是语言学家用来表示吸气音的办法。)所有现存的科伊桑语言只有非洲南部才有,但有两个例外。这两个例外是两个非常特别、充满吸气音的科伊桑语言,一个叫哈扎语,一个叫桑达韦语,孤立地存在于坦桑尼亚,距离非洲南部靠得最近的科伊桑语言有1000多英里。

In addition, Xhosa and a few other Niger-Congo languages of southern Africa are full of clicks. Even more unexpectedly, clicks or Khoisan words also appear in two Afroasiatic languages spoken by blacks in Kenya, stranded still farther from present Khoisan peoples than are the Hadza and Sandawe peoples of Tanzania. All this suggests that Khoisan languages and peoples formerly extended far north of their present southern African distribution, until they too, like the Pygmies, were engulfed by the blacks, leaving only linguistic legacies of their former presence. That's a unique contribution of the linguistic evidence, something we could hardly have guessed just from physical studies of living people.

此外,科萨语和非洲南部其他几种尼日尔-刚果语也是充满了吸气音。甚至更令人意想不到的是,在肯尼亚的黑人所说的两种阿非罗-亚细亚语中也出现了吸气音或科伊桑语的一些词,而肯尼亚的这些孤立的黑人比坦桑尼亚的说哈扎语和桑达韦语的人更加远离现今的科伊桑人。所有这一切表明,科伊桑语言和科伊桑民族的分布,以前并不只限于现今的非洲南部,而是到达了遥远的北方,后来他们也和俾格米人一样,被淹没在黑人的汪洋大海之中,只是在语言学上留下了他们过去存在的遗产。这是语言学证据的独特贡献,仅仅根据对活人的体质研究是几乎不可能推测出来的。

I have saved the most remarkable contribution of linguistics for last. If you look again at Figure 19.2, you'll see that the Niger-Congo language family is distributed all over West Africa and most of subequatorial Africa, apparently giving no clue as to where within that enormous range the family originated. However, Greenberg recognized that all Niger-Congo languages of subequatorial Africa belong to a single language subgroup termed Bantu. That subgroup accounts for nearly half of the 1,032 Niger-Congo languages and for more than half (nearly 200 million) of the Niger-Congo speakers. But all those 500 Bantu languages are so similar to each other that they have been facetiously described as 500 dialects of a single language.

我把语言学的最杰出的贡献留到最后来讨论。如果你再看一看图19.2,你就会看到尼日尔-刚果语系分布在整个西非和非洲赤道以南的大部分地区,这显然没有提供任何线索说明在那个广大的范围内这个语系究竟发源于何处。然而,格林伯格确认,非洲赤道以南地区的所有尼日尔-刚果语言属于一个叫做班图语的语支。这个语支占去了1032种尼日尔-刚果语言中的近一半语言,并占去了说尼日尔-刚果语言人数的一半以上(近两亿人)。但所有这500种班图语言彼此非常相似,所以有人开玩笑地说它们是一种语言500种方言。

Collectively, the Bantu languages constitute only a single, low-order subfamily of the Niger-Congo language family. Most of the 176 other subfamilies are crammed into West Africa, a small fraction of the entire Niger-Congo range. In particular, the most distinctive Bantu languages, and the non-Bantu Niger-Congo languages most closely related to Bantu languages, are packed into a tiny area of Cameroon and adjacent eastern Nigeria.

从整体来看,班图诸语言只构成了尼日尔-刚果语系中一个单一的、低一位的语族。另外176个语族的大多数都挤在西非,在尼日尔-刚果语系的整个分布范围内只占很小一部分。尤其是,最有特色的一些班图语言以及与班图语亲缘关系最近的非班图语的尼日尔-刚果诸语言,都挤在喀麦隆和邻近的尼日利亚东部的一个狭小地区内。

Evidently, the Niger-Congo language family arose in West Africa; the Bantu branch of it arose at the east end of that range, in Cameroon and Nigeria; and the Bantu then spread out of that homeland over most of subequatorial Africa. That spread must have begun long ago enough that the ancestral Bantu language had time to split into 500 daughter languages, but nevertheless recently enough that all those daughter languages are still very similar to each other. Since all other Niger-Congo speakers, as well as the Bantu, are blacks, we couldn't have inferred who migrated in which direction just from the evidence of physical anthropology.

显然,尼日尔-刚果语系起源于西非;它的班图语分支起源于这一分布范围的东端,即喀麦隆和尼日利亚;后来这支班图语又从它的故乡扩展到非洲赤道以南的大部分地区。这一扩展必定在很早以前就开始了,所以这个祖代的班图语有足够的时间分化为500种子代语言,但分化的时间也相当近,以致所有这些子代语言彼此仍然十分相似。由于所有其他说尼日尔-刚果语的人和说班图语的人一样都是黑人,我们不可能仅仅根据体质人类学的证据推断出谁向哪一个方面迁移。

To make this type of linguistic reasoning clear, let me give you a familiar example: the geographic origins of the English language. Today, by far the largest number of people whose first language is English live in North America, with others scattered over the globe in Britain, Australia, and other countries. Each of those countries has its own dialects of English. If we knew nothing else about language distributions and history, we might have guessed that the English language arose in North America and was carried overseas to Britain and Australia by colonists.

为了使这类语言学的推理变得明白易懂,让我举一个大家所熟悉的例子:英语的地理起源。今天,以英语为第一语言的数目最多的人生活在北美洲,其他人则分散在全球各地,如英国、澳大利亚和其他国家。每一个这样的国家都有自己的英语方言。如果对语言的分布和历史方面的知识不过如此,我们就可能会猜测英语起源于北美洲,后来才被殖民者传播到海外的英国和澳大利亚的。

But all those English dialects form only one low-order subgroup of the Germanic language family. All the other subgroups—the various Scandinavian, German, and Dutch languages—are crammed into northwestern Europe. In particular, Frisian, the other Germanic language most closely related to English, is confined to a tiny coastal area of Holland and western Germany. Hence a linguist would immediately deduce correctly that the English language arose in coastal northwestern Europe and spread around the world from there. In fact, we know from recorded history that English really was carried from there to England by invading Anglo-Saxons in the fifth and sixth centuries A.D.

但所有这些英语方言仅仅构成了日耳曼语族的一个低一位的语支。所有其他的语支——各种各样的斯堪的纳维亚语、德语和荷兰语——都挤在欧洲的西北部。尤其是,与英语亲缘关系最近的另一种日耳曼语——弗里西亚语只限于荷兰和德国西部的一个小小的沿海地区。因此,一个语言学家可能立刻正确地推断出英语起源于西北部沿海地区,并从那里传播到全世界。事实上,我们从历史记载得知,英语的确是在公元5世纪和6世纪时被入侵的盎格鲁-撒克逊人从那里传到英国来的。

Essentially the same line of reasoning tells us that the nearly 200 million Bantu people, now flung over much of the map of Africa, arose from Cameroon and Nigeria. Along with the North African origins of Semites and the origins of Madagascar's Asians, that's another conclusion that we couldn't have reached without linguistic evidence.

基本上相同的推理告诉我们,如今在非洲地图上占据很大一块地方的近两亿的班图人起源于喀麦隆和尼日利亚。连同闪米特人起源于北非和马达加斯加人起源于亚洲一样,这是又一个我们在没有语言学证据的情况下能够得出的结论。

We had already deduced, from Khoisan language distributions and the lack of distinct Pygmy languages, that Pygmies and Khoisan peoples had formerly ranged more widely, until they were engulfed by blacks. (I'm using “engulfing” as a neutral all-embracing word, regardless of whether the process involved conquest, expulsion, interbreeding, killing, or epidemics.) We've now seen, from Niger-Congo language distributions, that the blacks who did the engulfing were the Bantu. The physical and linguistic evidence considered so far has let us infer these prehistoric engulfings, but it still hasn't solved their mysteries for us. Only the further evidence that I'll now present can help us answer two more questions: What advantages enabled the Bantu to displace the Pygmies and Khoisan? When did the Bantu reach the former Pygmy and Khoisan homelands?

我们已经根据科伊桑语言的分布和俾格米人没有自己的特有语言这一点推断出,俾格米人和科伊桑人以前分布较广,后来被黑人的汪洋大海所淹没了。(我把“淹没”当作一个中性的、无所不包的词来使用,不管这个过程是征服、驱逐、混种繁殖、杀害或是流行病。)根据尼日尔-刚果语言的分布,我们现在明白了,“淹没”俾格米人和科伊桑人的黑人是班图人。迄今所考虑的体质证据和语言证据使我们推断出这些发生在史前的“淹没”现象,但仍然没有为我们解开这些“淹没”现象之谜。只有我接着将要提出的进一步证据才能帮助我们回答另外两个问题:是什么有利条件使班图人得以取代俾格米人和科伊桑人的地位?班图人是在什么时候到达俾格米人和科伊桑人以前的家园的?

TO APPROACH THE question about the Bantu's advantages, let's examine the remaining type of evidence from the living present—the evidence derived from domesticated plants and animals. As we saw in previous chapters, that evidence is important because food production led to high population densities, germs, technology, political organization, and other ingredients of power. Peoples who, by accident of their geographic location, inherited or developed food production thereby became able to engulf geographically less endowed people.

为了回答关于班图人的有利条件问题,让我们研究一下眼前的活证据——来自驯化了的动植物的证据。我们在前面的几章看到,这方面的证据是非常重要的,因为粮食生产带来了高密度的人口、病菌、技术、政治组织和其他力量要素。由于地理位置的偶然因素而继承或发展了粮食生产的民族,因此就能够“淹没”地理条件较差的民族。

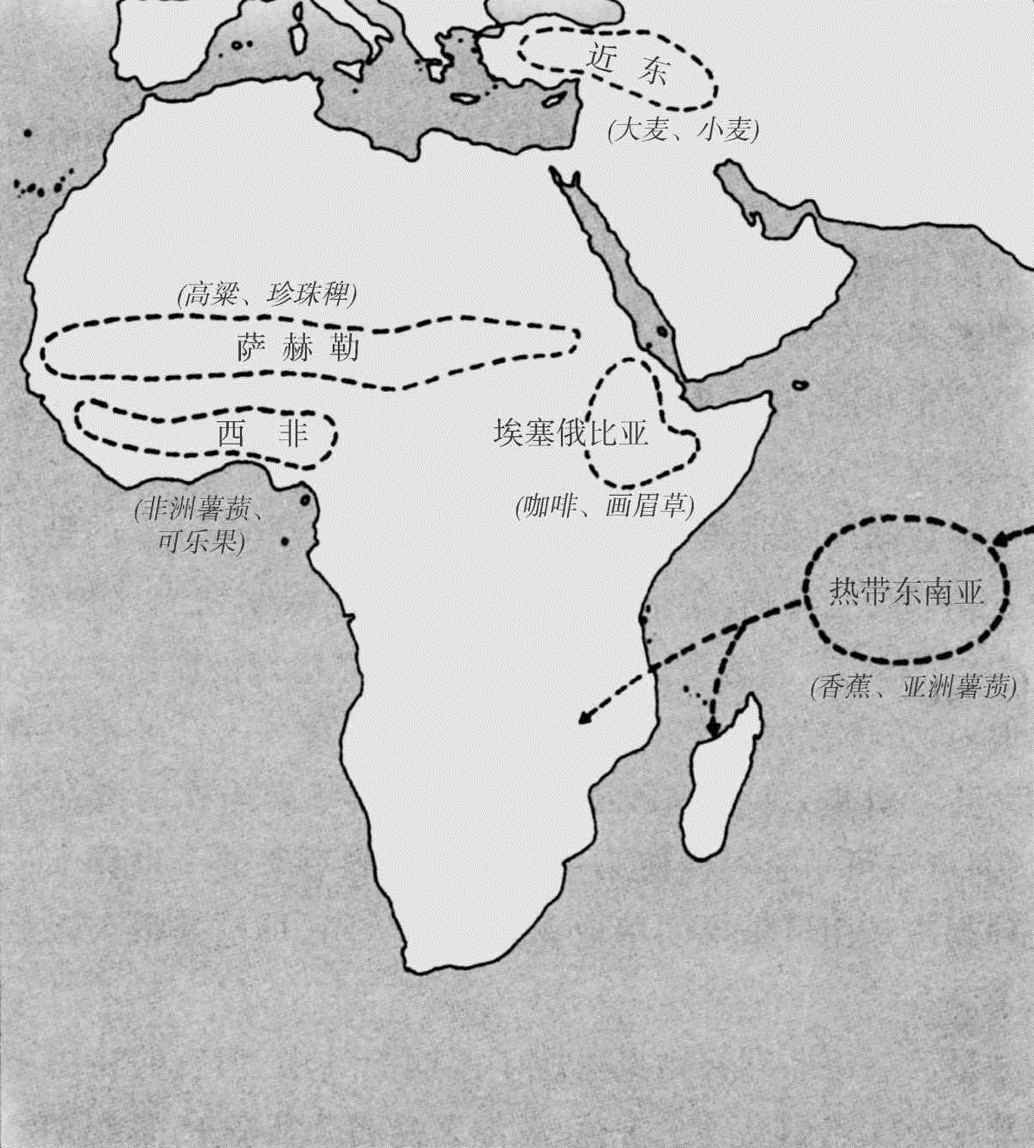

When Europeans reached sub-Saharan Africa in the 1400s, Africans were growing five sets of crops (Figure 19.3), each of them laden with significance for African history. The first set was grown only in North Africa, extending to the highlands of Ethiopia. North Africa enjoys a Mediterranean climate, characterized by rainfall concentrated in the winter months. (Southern California also experiences a Mediterranean climate, explaining why my basement and that of millions of other southern Californians often gets flooded in the winter but infallibly dries out in the summer.) The Fertile Crescent, where agriculture arose, enjoys that same Mediterranean pattern of winter rains.

当欧洲人于15世纪初到达非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区时,非洲人在种植5组作物(图19.3),每一组作物都对非洲的历史具有重大的意义。第一组作物只在北非种植,一直延伸到埃塞俄比亚高原。北非属于地中海型气候,其特点是雨量集中在冬季的几个月。(南加利福尼亚也属于地中海型气候,这就说明为什么我的地下室和其他许多南加利福尼亚人的地下室常常在冬天被淹,而又总是在夏天变得十分干燥。)农业发源地的新月沃地也是属于冬季多雨的地中海型气候。

Origins of African crops, with examples

非洲作物原产地举例

Figure 19.3. The areas of origin of crops grown traditionally in Africa (that is, before the arrival of crops carried by colonizing Europeans), with examples of two crops from each area.

图19.3 非洲传统种植的作物(即在非洲殖民的欧洲人带来的作物到达之前的作物)的原产地区,每一地区举两种作物作例子。

Hence North Africa's original crops all prove to be ones adapted to germinating and growing with winter rains, and known from archaeological evidence to have been first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent beginning around 10,000 years ago. Those Fertile Crescent crops spread into climatically similar adjacent areas of North Africa and laid the foundations for the rise of ancient Egyptian civilization. They include such familiar crops as wheat, barley, peas, beans, and grapes. These are familiar to us precisely because they also spread into climatically similar adjacent areas of Europe, thence to America and Australia, and became some of the staple crops of temperate-zone agriculture around the world.

因此,北非原来的作物证明都是适合在冬天雨季里发芽生长的作物,考古的证据表明,它们在大约1万年前开始首先在新月沃地得到驯化。这些新月沃地的作物传播到气候相似的北非邻近地区,为古代埃及文明的兴起奠定了基础。它们包括诸如小麦、大麦、豌豆、菜豆和葡萄之类为人们所熟悉的作物。这些作物之所以为我们所熟悉,完全是因为它们也传播到气候相似的欧洲邻近地区,并由欧洲传播到美洲和澳大利亚,从而成为全世界温带农业的一些主要作物。

As one travels south in Africa across the Saharan desert and reencounters rain in the Sahel zone just south of the desert, one notices that Sahel rains fall in the summer rather than in the winter. Even if Fertile Crescent crops adapted to winter rain could somehow have crossed the Sahara, they would have been difficult to grow in the summer-rain Sahel zone. Instead, we find two sets of African crops whose wild ancestors occur just south of the Sahara, and which are adapted to summer rains and less seasonal variation in day length. One set consists of plants whose ancestors are widely distributed from west to east across the Sahel zone and were probably domesticated there. They include, notably, sorghum and pearl millet, which became the staple cereals of much of sub-Saharan Africa. Sorghum proved so valuable that it is now grown in areas with hot, dry climates on all the continents, including in the United States.

当你在非洲越过撒哈拉沙漠向南旅行,并在沙漠南部边缘的萨赫勒地带重新碰到下雨时,你会注意到萨赫勒地带下雨是在夏天,而不是在冬天。即使适应冬雨的新月沃地作物能够设法越过撒哈拉沙漠,它们也可能难以在夏季多雨的萨赫勒地带生长。我们发现有两组非洲作物,它们的野生祖先正好出现在撒哈拉沙漠以南,它们适应了夏季的雨水和日长方面的较少的季节性变化。其中一组包含这样一些植物,它们的祖先在萨赫勒地带从东到西有广泛的分布,可能就是在那里驯化的。值得注意的是,它们包括高粱和珍珠稗,而这两种作物成为非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南广大地区的主要谷物。高粱证明是一种很有价值的作物,现在在各大洲的炎热、干旱地区(包括美国)都有种植。

The other set consists of plants whose wild ancestors occur in Ethiopia and were probably domesticated there in the highlands. Most are still grown mainly just in Ethiopia and remain unknown to Americans—including Ethiopia's narcotic chat, its banana-like ensete, its oily noog, its finger millet used to brew its national beer, and its tiny-seeded cereal called teff, used to make its national bread. But every reader addicted to coffee can thank ancient Ethiopian farmers for domesticating the coffee plant. It remained confined to Ethiopia until it caught on in Arabia and then around the world, to sustain today the economies of countries as far-flung as Brazil and Papua New Guinea.

另一组包含这样一些植物,它们的野生祖先出现在埃塞俄比亚,可能是在那里的高原地区驯化的。其中大多数仍然主要在埃塞俄比亚种植,美国人对它们仍然一无所知——这些作物包括埃塞俄比亚的有麻醉作用的球果、像香蕉一样的埃塞俄比亚香蕉、含油的努格、用来酿制国产啤酒的龙爪稗和用来做国产面包的叫做画眉草的籽粒很小的谷物。但每一个喝咖啡成瘾的读者可以感谢古代的埃塞俄比亚农民,是他们驯化了咖啡植物。咖啡本来只在埃塞俄比亚种植,后来在阿拉伯半岛进而又在全世界受到欢迎,在今天成了像巴西和巴布亚新几内亚这样遥远的国家的经济支柱。

The next-to-last set of African crops arose from wild ancestors in the wet climate of West Africa. Some, including African rice, have remained virtually confined there; others, such as African yams, spread throughout other areas of sub-Saharan Africa; and two, the oil palm and kola nut, reached other continents. West Africans were chewing the caffeine-containing nuts of the latter as a narcotic, long before the Coca-Cola Company enticed first Americans and then the world to drink a beverage originally laced with its extracts.

倒数第二组非洲作物来自生长在西非湿润气候下的野生祖先。其中有些作物,包括非洲稻,几乎始终限于在当地种植;另一些作物,如非洲薯蓣,已经传播到非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南的所有其他地区;还有两种作物——油棕和可乐果——已经传播到其他大陆。西非人把可乐果的含咖啡因的坚果当作麻醉品来嚼食,而可口可乐公司诱使第一批美国人和后来的全世界人去喝一种原来是用可乐果的萃取物调制的饮料,那已是很久以后的事了。

The last batch of African crops is also adapted to wet climates but provides the biggest surprise of Figure 19.3. Bananas, Asian yams, and taro were already widespread in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1400s, and Asian rice was established on the coast of East Africa. But those crops originated in tropical Southeast Asia. Their presence in Africa would astonish us, if the presence of Indonesian people on Madagascar had not already alerted us to Africa's prehistoric Asian connection. Did Austronesians sailing from Borneo land on the East African coast, bestow their crops on grateful African farmers, pick up African fishermen, and sail off into the sunrise to colonize Madagascar, leaving no other Austronesian traces in Africa?

最后一组非洲作物也适应了湿润的气候,但它们在图19.3中却最令人感到意外。香蕉、亚洲薯蓣和芋艿在15世纪初已在非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区广为种植,而非洲水稻也已在东非海岸地区移植生长。但这些作物都发源于热带东南亚。如果印度尼西亚人在马达加斯加岛上出现,还不曾使我们认识到非洲在史前阶段与亚洲的联系,那么这些作物在非洲出现就可能会使我们感到惊奇。是不是当年从婆罗洲启航的南岛人在东非海岸登陆,把他们的作物赠与满心感激的非洲农民,又搭载了一些非洲渔民,然后扬帆向东方驶去,到马达加斯加岛去拓殖,因而在非洲没有留下其他任何关于南岛人的蛛丝马迹?

The remaining surprise is that all of Africa's indigenous crops—those of the Sahel, Ethiopia, and West Africa—originated north of the equator. Not a single African crop originated south of it. This already gives us a hint why speakers of Niger-Congo languages, stemming from north of the equator, were able to displace Africa's equatorial Pygmies and subequatorial Khoisan people. The failure of the Khoisan and Pygmies to develop agriculture was due not to any inadequacy of theirs as farmers but merely to the accident that southern Africa's wild plants were mostly unsuitable for domestication. Neither Bantu nor white farmers, heirs to thousands of years of farming experience, were subsequently able to develop southern African native plants into food crops.

还有一个令人感到意外的地方是:所有非洲本地作物——萨赫勒、埃塞俄比亚和西非的作物——都起源于赤道以北地区。没有哪一种非洲作物是起源于赤道以南地区的。这就给了我们一个暗示,告诉我们来自赤道以北、说尼日尔-刚果语的人何以能取代非洲赤道地区的俾格米人和赤道以南的科伊桑人。科伊桑人和俾格米人之所以未能发展出农业,不是由于他们没有农民的资格,而仅仅是由于碰巧非洲南部的野生植物大都不适于驯化。无论是班图农民还是白人农民,尽管他们继承了几千年的农业经验,后来还是没有能把非洲南部的本地植物培育成粮食作物。

Africa's domesticated animal species can be summarized much more quickly than its plants, because there are so few of them. The sole animal that we know for sure was domesticated in Africa, because its wild ancestor is confined there, is a turkeylike bird called the guinea fowl. Wild ancestors of domestic cattle, donkeys, pigs, dogs, and house cats were native to North Africa but also to Southwest Asia, so we can't yet be certain where they were first domesticated, although the earliest dates currently known for domestic donkeys and house cats favor Egypt. Recent evidence suggests that cattle may have been domesticated independently in North Africa, Southwest Asia, and India, and that all three of those stocks have contributed to modern African cattle breeds. Otherwise, all the remainder of Africa's domestic mammals must have been domesticated elsewhere and introduced as domesticates to Africa, because their wild ancestors occur only in Eurasia. Africa's sheep and goats were domesticated in Southwest Asia, its chickens in Southeast Asia, its horses in southern Russia, and its camels probably in Arabia.

至于非洲的驯化动物,概括地介绍起来可以比介绍它的植物快得多,因为那里的驯化动物实在太少。我们确切知道是在非洲驯化的唯一动物,是一种叫做珍珠鸡的像火鸡一样的鸟,因为它的野生祖先只有非洲才有。驯养的牛、驴、猪、狗和家猫的野生祖先原产北非,但西南亚也有,所以我们还不能肯定它们最早是在什么地方驯化的,虽然目前已知的年代最早的家驴和家猫出现在埃及。近来的证据表明,牛可能是在北非、西南亚和印度各自独立驯化出来的,而这3个地方的品种与现代非洲牛的品种都有关系。除此以外,非洲其余所有的驯养的哺乳动物想必都是在别处驯化后引进的,因为它们的野生祖先只出现在欧亚大陆。非洲的绵羊和山羊是在西南亚驯化的,它的鸡是在东南亚驯化的,它的马是在俄罗斯南部驯化的,它的骆驼可能是在阿拉伯半岛驯化的。

The most unexpected feature of this list of African domestic animals is again a negative one. The list includes not a single one of the big wild mammal species for which Africa is famous and which it possesses in such abundance—its zebras and wildebeests, its rhinos and hippos, its giraffes and buffalo. As we'll see, that reality was as fraught with consequences for African history as was the absence of native domestic plants in subequatorial Africa.

这个关于非洲家畜的清单的最意想不到的特点又一次是负面的。非洲是以大型野生哺乳动物而著称的,它们的数量也非常丰富——有斑马和牛羚,有犀牛和河马,有长颈鹿和野牛,但没有一种上了那张清单。我们还将看到,这个事实与非洲赤道以南没有本地的驯化植物一样,对非洲的历史产生了深远的影响。

This quick tour through Africa's food staples suffices to show that some of them traveled a long way from their points of origin, both inside and outside Africa. In Africa as elsewhere in the world, some peoples were much “luckier” than others, in the suites of domesticable wild plant and animal species that they inherited from their environment. By analogy with the engulfing of Aboriginal Australian hunter-gatherers by British colonists fed on wheat and cattle, we have to suspect that some of the “lucky” Africans parlayed their advantage into engulfing their African neighbors. Now, at last, let's turn to the archaeological record to find out who engulfed whom when.

对非洲主要粮食产品的这一快速巡视足以看出,其中有些粮食产品是从它们在非洲内外的发源地经过长途跋涉而到来的。在非洲和在世界其他地方一样,有些族群由于从环境继承了整个系列的可驯化的野生动植物而比另一些族群“幸运”得多。澳大利亚土著的狩猎采集族群被以小麦和牛群为生的英国殖民者所“淹没”,由这一事实来类推,我们不得不怀疑有些“幸运的”非洲人利用自己的优势来“淹没”他们的非洲人邻居。现在,我们终于可以求助于考古记录去看一看到底是谁在什么时候“淹没”了谁。

WHAT CAN ARCHAEOLOGY can tell us about actual dates and places for the rise of farming and herding in Africa? Any reader steeped in the history of Western civilization would be forgiven for assuming that African food production began in ancient Egypt's Nile Valley, land of the pharaohs and pyramids. After all, Egypt by 3000 B.C. was undoubtedly the site of Africa's most complex society, and one of the world's earliest centers of writing. In fact, though, possibly the earliest archaeological evidence for food production in Africa comes instead from the Sahara.

关于非洲农业和畜牧业出现的实际年代和地点,考古学能告诉我们一些什么呢?任何一个潜心研究西方文明史的读者,如果他想当然地认为,非洲的粮食生产肇始于法老和金字塔之乡古埃及的尼罗河河谷,那么他是可以得到原谅的。毕竟,到公元前3000年,埃及无疑已是非洲最复杂社会的所在地,并是世界上最早使用文字的中心之一。然而,事实上,非洲粮食生产可能最早的考古证据却是来自撒哈拉沙漠。

Today, of course, much of the Sahara is so dry that it cannot support even grass. But between about 9000 and 4000 B.C. the Sahara was more humid, held numerous lakes, and teemed with game. In that period, Saharans began to tend cattle and make pottery, then to keep sheep and goats, and they may also have been starting to domesticate sorghum and millet. Saharan pastoralism precedes the earliest known date (5200 B.C.) for the arrival of food production in Egypt, in the form of a full package of Southwest Asian winter crops and livestock. Food production also arose in West Africa and Ethiopia, and by around 2500 B.C. cattle herders had already crossed the modern border from Ethiopia into northern Kenya.

当然,今天撒哈拉沙漠的很大一部分地区干燥得寸草不生。但在公元前9000年到公元前4000年之间,撒哈拉沙漠比较湿润,有许多湖泊,到处都是猎物。在那个时期,撒哈拉人开始养牛和制陶,后来又养绵羊和山羊,他们可能也已着手驯化高粱和黍。撒哈拉的放牧业早于以整个西南亚冬季作物和牲口的形式出现的粮食生产引进埃及的已知最早年代(公元前5200年)。粮食生产也出现在西非和埃塞俄比亚,而到了公元前2500年左右,牧牛人已经越过现代的边界,从埃塞俄比亚进入肯尼亚北部。

While those conclusions rest on archaeological evidence, there is also an independent method for dating the arrival of domestic plants and animals: by comparing the words for them in modern languages. Comparisons of terms for plants in southern Nigerian languages of the Niger-Congo family show that the words fall into three groups. First are cases in which the word for a particular crop is very similar in all those southern Nigerian languages. Those crops prove to be ones like West African yams, oil palm, and kola nut—plants that were already believed on botanical and other evidence to be native to West Africa and first domesticated there. Since those are the oldest West African crops, all modern southern Nigerian languages inherited the same original set of words for them.

虽然这些结论是以考古证据为基础的,但也有一种独立的方法来判定驯化动植物引进的年代:比较现代语言中用来指称它们的词汇。比较一下尼日尔-刚果语系的尼日利亚南部一些语言中植物的名称,就可以看出这些词分为3类。第一类中用来指称某种作物的词,在尼日利亚南部的所有这些语言中都十分相似。这些作物证明就是西非的薯蓣、油棕和可乐果之类的作物——也就是人们按照植物学证据和其他证据认为原产西非并最早在那里驯化的植物。由于它们是西非最古老的作物,所有尼日利亚南部的现代语言都继承了原来用以指称它们的同一套词汇。

Next come crops whose names are consistent only among the languages falling within a small subgroup of those southern Nigerian languages. Those crops turn out to be ones believed to be of Indonesian origin, such as bananas and Asian yams. Evidently, those crops reached southern Nigeria only after languages began to break up into subgroups, so each subgroup coined or received different names for the new plants, which the modern languages of only that particular subgroup inherited. Last come crop names that aren't consistent within language groups at all, but instead follow trade routes. These prove to be New World crops like corn and peanuts, which we know were introduced into Africa after the beginnings of transatlantic ship traffic (A.D. 1492) and diffused since then along trade routes, often bearing their Portuguese or other foreign names.

其次,有些作物的名称只有在属于尼日利亚南部那些语言的一个小语支的语言中才保持一致。原来,据认为这些作物来自印度尼西亚,如香蕉和亚洲薯蓣。显然,这些作物只是在一些语言开始分化成一些语支之后才到达尼日利亚的南部的,这样,每一个语支为这些新来的植物发明了或接受了一些不同的名称,而这些名称只有属于那一特定语支的一些现代语言才继承了下来。最后一批作物的名称在一些语族内是完全不一致的,而是与贸易路线有关。这些作物证明是来自新大陆的作物,如玉米和花生,我们知道这些作物是在横渡大西洋的航运开始后(公元1492年)才引进非洲,并从那以后沿贸易路线传播,因此它们常常带有葡萄牙的名字或别的外国名字。

Thus, even if we possessed no botanical or archaeological evidence whatsoever, we would still be able to deduce from the linguistic evidence alone that native West African crops were domesticated first, that Indonesian crops arrived next, and that finally the European introductions came in. The UCLA historian Christopher Ehret has applied this linguistic approach to determining the sequence in which domestic plants and animals became utilized by the people of each African language family. By a method termed glottochronology, based on calculations of how rapidly words tend to change over historical time, comparative linguistics can even yield estimated dates for domestications or crop arrivals.

因此,即使我们没有掌握任何植物学的或考古学的证据,我们也仍然能够仅仅靠语言学的证据来予以推断:先是驯化西非本地的作物,其次是引进印度尼西亚的作物,最后是欧洲人带来的美洲作物。加利福尼亚大学洛杉矶分校的历史学家克里斯托弗·埃雷特运用这种语言学方法来确定驯化的动植物为属于每一个非洲语系的人所利用的顺序。有一种方法叫做词源统计分析法,其根据就是计算出词通常在历史上的变化速度。比较语言学家利用这种方法甚至能估计出作物驯化或引进的年代。

Putting together direct archaeological evidence of crops with the more indirect linguistic evidence, we deduce that the people who were domesticating sorghum and millet in the Sahara thousands of years ago spoke languages ancestral to modern Nilo-Saharan languages. Similarly, the people who first domesticated wet-country crops of West Africa spoke languages ancestral to the modern Niger-Congo languages. Finally, speakers of ancestral Afroasiatic languages may have been involved in domesticating the crops native to Ethiopia, and they certainly introduced Fertile Crescent crops to North Africa.

把关于作物的直接的考古学证据同比较间接的语言学证据结合起来,我们就可以推断出几千年前在撒哈拉驯化高粱和黍的人所说的语言是现代尼罗-撒哈拉语的祖代语言。同样,最早驯化西非湿润地区作物的人所说的语言是现代尼日尔-刚果诸语言的祖代语言。最后,说阿非罗-亚细亚祖代语言的人可能驯化过埃塞俄比亚的本地作物,而且他们肯定也是把新月沃地的作物引进北非的人。

Thus, the evidence derived from plant names in modern African languages permits us to glimpse the existence of three languages being spoken in Africa thousands of years ago: ancestral Nilo-Saharan, ancestral Niger-Congo, and ancestral Afroasiatic. In addition, we can glimpse the existence of ancestral Khoisan from other linguistic evidence, though not that of crop names (because ancestral Khoisan people domesticated no crops). Now surely, since Africa harbors 1,500 languages today, it is big enough to have harbored more than four ancestral languages thousands of years ago. But all those other languages must have disappeared—either because the people speaking them survived but lost their original language, like the Pygmies, or because the people themselves disappeared.

因此,来自现代非洲语言中植物名称的证据,使我们一眼就能看明白几千年前非洲存在3种语言:祖代的尼罗-撒哈拉语、祖代的尼日尔-刚果语和祖代的阿非罗-亚细亚语。此外,我们还能根据其他的语言学证据一眼就能看明白祖代科伊桑语的存在,虽然不是根据作物名称这个证据(因为科伊桑人的祖先没有驯化过任何作物)。既然非洲今天有1500种语言,那么几千年前它肯定不会只有这4种祖代语言。但所有其他这些语言想必都已消失——这或者是由于说这些语言的人虽然生存了下来,但却失去了自己本来的语言,如俾格米人,或者是由于连这些人本身都消失了。

The survival of modern Africa's four native language families (that is, the four other than the recently arrived Austronesian language of Madagascar) isn't due to the intrinsic superiority of those languages as vehicles for communication. Instead, it must be attributed to a historical accident: ancestral speakers of Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Congo, and Afroasiatic happened to be living at the right place and time to acquire domestic plants and animals, which let them multiply and either replace other peoples or impose their language. The few modern Khoisan speakers survived mainly because of their isolation in areas of southern Africa unsuitable for Bantu farming.

现代非洲本土的4个语系(即除去最近传入的马达加斯加的南岛语的4个语系)之所以能幸存下来,不是由于这些语言作为交流工具有什么内在的优越性。相反,这应归因于一个历史的偶然因素:说尼罗-撒哈拉语、尼日尔-刚果语和阿非罗-亚细亚语的人的祖先,碰巧在最合适的时间生活在最合适的地点,使他们获得了作物和家畜,从而使他们人口繁衍,并且取代了其他族群或将自己的语言强加给其他族群。现代的为数不多的说科伊桑语的人能够幸存下来,主要是由于他们生活在非洲南部不适于班图人的农业的、与世隔绝的地区。

BEFORE WE TRACE Khoisan survival beyond the Bantu tide, let's see what archaeology tells us about Africa's other great prehistoric population movement—the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar. Archaeologists exploring Madagascar have now proved that Austronesians had arrived at least by A.D. 800, possibly as early as A.D. 300. There the Austronesians encountered (and proceeded to exterminate) a strange world of living animals as distinctive as if they had come from another planet, because those animals had evolved on Madagascar during its long isolation. They included giant elephant birds, primitive primates called lemurs as big as gorillas, and pygmy hippos. Archaeological excavations of the earliest human settlements on Madagascar yield remains of iron tools, livestock, and crops, so the colonists were not just a small canoeload of fishermen blown off course; they formed a full-fledged expedition. How did that prehistoric 4,000-mile expedition come about?

在我们考查科伊桑人如何躲过班图人的移民浪潮而幸存下来这一点之前,让我们先来看一看,关于非洲史前期的另一次人口大迁移——南岛人在马达加斯加岛的殖民情况,考古学告诉了我们一些什么。在马达加斯加调查的考古学家们现已证明,南岛人至少不迟于公元800年,也可能早在公元300年,即已到达马达加斯加。南岛人在那里碰到了(并着手消灭)一个陌生的动物世界,这些动物非常特别,好像它们是来自另一个星球,因为这些动物是在长期与世隔绝的情况下在马达加斯加演化出来的。它们中有大隆鸟,有同大猩猩一般大的叫做狐猴的原始灵长目动物,还有矮小的河马。对马达加斯加岛上最早的人类定居点的考古发掘,出土了一些铁器、牲畜和作物的残存,从这点来看,那些殖民者就不完全是乘坐小小独木舟的被风吹离航线的渔民;他们是一个经过充分准备的探险队。这次史前的行程4000英里的探险是如何实现的呢?

One hint is in an ancient book of sailors' directions, the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, written by an anonymous merchant living in Egypt around A.D. 100. The merchant describes an already thriving sea trade connecting India and Egypt with the coast of East Africa. With the spread of Islam after A.D. 800, Indian Ocean trade becomes well documented archaeologically by copious quantities of Mideastern (and occasionally even Chinese!) products such as pottery, glass, and porcelain in East African coastal settlements. The traders waited for favorable winds to let them cross the Indian Ocean directly between East Africa and India. When the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama became the first European to sail around the southern cape of Africa and reached the Kenya coast in 1498, he encountered Swahili trading settlements and picked up a pilot who guided him on that direct route to India.

有一本古代航海书对此提供了一条线索。这本书名叫《欧力斯里洋 [2]航行记》,是公元100年左右一个生活在埃及的无名氏商人写的。这位商人描述了当时已相当繁荣的把印度和埃及与东非海岸连接起来的海上贸易路线。随着公元800年后伊斯兰教的传播,印度洋贸易也兴旺发达起来,有充分的考古文献证明,在东非沿海定居点遗址中发现了大量中东的(偶尔甚至还有中国的!)产品,如陶器、玻璃器皿和瓷器。商人们等待着有利的风向,好让他们横渡中非和印度之间的印度洋。1498年,葡萄牙航海家法斯科·达·伽马 [3]成为绕过非洲南端到达肯尼亚海岸的第一个欧洲人,他碰到了斯瓦希里人的一些贸易点,并在那里带上一个水手领着他走上那条通往印度的直达航线。

But there was an equally vigorous sea trade from India eastward, between India and Indonesia. Perhaps the Austronesian colonists of Madagascar reached India from Indonesia by that eastern trade route and then fell in with the westward trade route to East Africa, where they joined with Africans and discovered Madagascar. That union of Austronesians and East Africans lives on today in Madagascar's basically Austronesian language, which contains loan words from coastal Kenyan Bantu languages. But there are no corresponding Austronesian loan words in Kenyan languages, and other traces of Austronesians are very thin on the ground in East Africa: mainly just Africa's possible legacy of Indonesian musical instruments (xylophones and zithers) and, of course, the Austronesian crops that became so important in African agriculture. Hence one wonders whether Austronesians, instead of taking the easier route to Madagascar via India and East Africa, somehow (incredibly) sailed straight across the Indian Ocean, discovered Madagascar, and only later got plugged into East African trade routes. Thus, some mystery remains about Africa's most surprising fact of human geography.

但从印度向东,在印度与印度尼西亚之间,也有一条同样兴旺发达的海上贸易路线。也许,马达加斯加的南岛人殖民者就是从这条向东的贸易路线从印度尼西亚到达印度,后来偶然碰上了向西的通往东非的贸易路线,在那里加入了非洲人的行列,和他们一起发现了马达加斯加。南岛人与东非人的这种结合,今天仍在马达加斯加的语言中体现出来,马达加斯加的语言基本上是南岛语,只是从肯尼亚沿海的一些班图语中借用了一些单词。但在肯尼亚的一些语言中却没有相应的来自南岛语的借用词,而且在东非的土地上也几乎没有留下多少南岛人的其他痕迹:主要地只有可能是印度尼西亚乐器在非洲的遗产(木琴和筝)以及当然还有在非洲农业占有十分重要地位的南岛人的作物。因此,人们怀疑南岛人是不是没有走经由印度和东非到达马达加斯加的比较容易的路线,而是设法(令人难以置信地)直接渡过印度洋,发现了马达加斯加,只是后来才加入了东非的贸易路线。因此,关于非洲最令人惊异的人类地理学上的事实多少还仍然是个谜。

WHAT CAN ARCHAEOLOGY tell us about the other great population movement in recent African prehistory—the Bantu expansion? We saw from the twin evidence of modern peoples and their languages that sub-Saharan Africa was not always a black continent, as we think of it today. Instead, this evidence suggested that Pygmies had once been widespread in the rain forest of Central Africa, while Khoisan peoples had been widespread in drier parts of subequatorial Africa. Can archaeology test those assumptions?

关于非洲史前史上最近的另一次人口大迁移——班图人的扩张,考古学能告诉我们一些什么呢?根据现代民族和他们的语言这个双重证据,我们知道非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区并不总是我们今天所认为的黑色的大陆。这个证据倒是表明了俾格米人曾在中非雨林中有广泛分布,而科伊桑族群在非洲赤道以南较干旱地区亦甚为普遍。考古学能不能对这些假定进行验证呢?

In the case of the Pygmies, the answer is “not yet,” merely because archaeologists have yet to discover ancient human skeletons from the Central African forests. For the Khoisan, the answer is “yes.” In Zambia, to the north of the modern Khoisan range, archaeologists have found skulls of people possibly resembling the modern Khoisan, as well as stone tools resembling those that Khoisan peoples were still making in southern Africa at the time Europeans arrived.

就俾格米人来说,答案是“还不能”,这仅仅是因为考古学家们还必须从中非森林中去发现古人类的骨骼。对于科伊桑人,答案是“能”。在现代科伊桑人分布地区北面的赞比亚,考古学家不但发现了与科伊桑族群在欧洲人到达时仍在非洲南部制作的那种石器相似的石器,而且也发现了可能与现代科伊桑人相似的一些人的头骨。

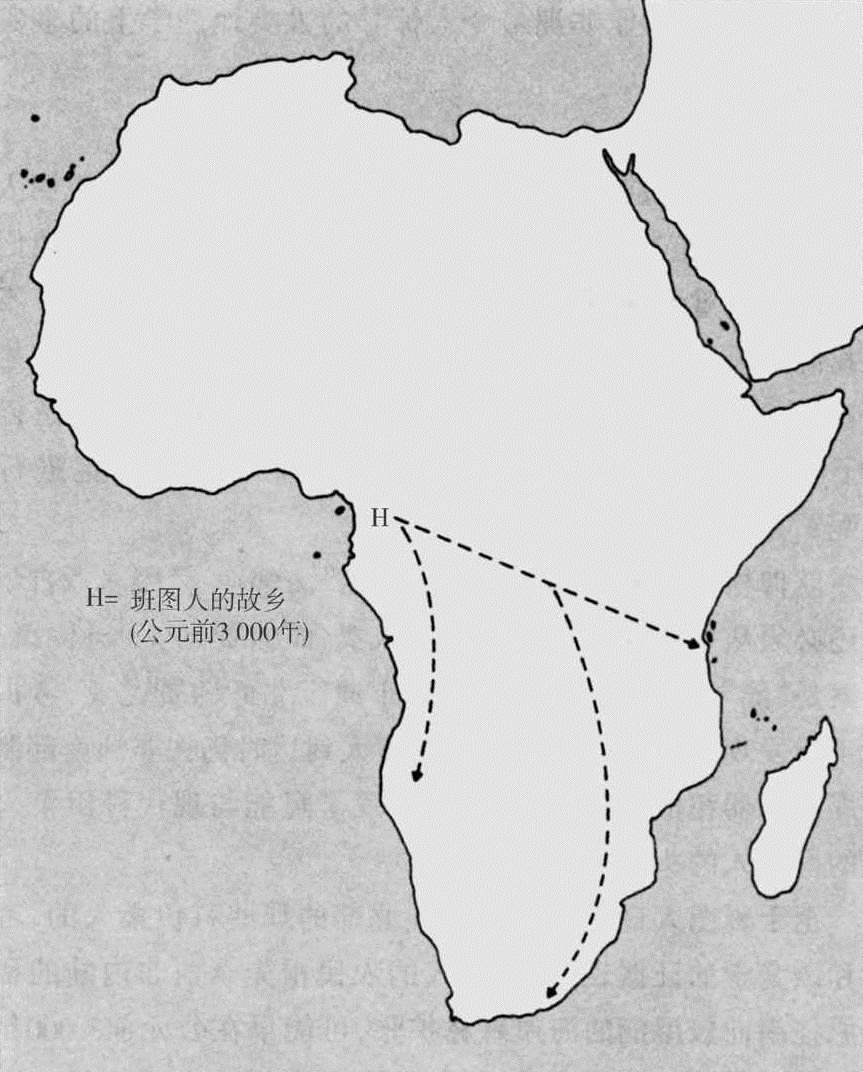

As for how the Bantu came to replace those northern Khoisan, archaeological and linguistic evidence suggest that the expansion of ancestral Bantu farmers from West Africa's inland savanna south into its wetter coastal forest may have begun as early as 3000 B.C. (Figure 19.4). Words still widespread in all Bantu languages show that, already then, the Bantu had cattle and wet-climate crops such as yams, but that they lacked metal and were still engaged in much fishing, hunting, and gathering. They even lost their cattle to disease borne by tsetse flies in the forest. As they spread into the Congo Basin's equatorial forest zone, cleared gardens, and increased in numbers, they began to engulf the Pygmy hunter-gatherers and compress them into the forest itself.

至于班图人最后是怎样取代北部的那些科伊桑人的,考古学和语言学的证据表明,班图人的农民祖先从西非内陆的稀树草原往南向较湿润的海岸森林扩张,可能早在公元前3000年就已开始了(图19.4)。在所有班图语言中仍然广泛使用的一些词表明,那时班图人已经有了牛和薯蓣之类的在湿润气候下生长的作物,但他们还没有金属制品,并且仍然从事大量的捕鱼、狩猎和采集活动。他们的牛群甚至由于森林中的采采蝇传播的疾病而被毁掉。他们进入刚果河流域的赤道森林地带,在那里开垦园地,并且增加了人口。这时,他们开始“淹没”了从事狩猎和采集的俾格米人,把他们一步步挤进森林。

The Bantu expansion: 3000 BC to AD 500

班图人的扩张:公元前3000年至公元500年

Figure 19.4. Approximate paths of the expansion that carried people speaking Bantu languages, originating from a homeland (designated H) 'n the northwest comer of the current Bantu area, over eastern and southern Africa between 3000 B. C. and A. D. 500.

图19.4 公元前3000年至公元500年之间说班图语的人扩张时行经的大致路线,由现今班图地区西北角的故乡(用H标出)出发,扩张到非洲的东部和南部。

By soon after 1000 B.C. the Bantu had emerged from the eastern side of the forest into the more open country of East Africa's Rift Valley and Great Lakes. Here they encountered a melting pot of Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan farmers and herders growing millet and sorghum and raising livestock in drier areas, along with Khoisan hunter-gatherers. Thanks to their wet-climate crops inherited from their West African homeland, the Bantu were able to farm in wet areas of East Africa unsuitable for all those previous occupants. By the last centuries B.C. the advancing Bantu had reached the East African coast.

公元前1000年后不久,班图人从森林的东缘走出来,进入了东非有裂谷和大湖的比较开阔的地带。在这里他们碰到了一个民族大熔炉,这里有在较干旱地区种植黍和高粱以及饲养牲畜的、说阿非罗-亚细亚语和尼罗-撒哈拉语的农民和牧人,还有以狩猎和采集为生的科伊桑人。由于从他们的西非家园继承下来的适应湿润气候的作物,这些班图人得以在不适合以往所有那些当地人耕种的东非气候湿润地区进行耕种。到了公元前的最后几个世纪,不断前进的班图人到达了东非海岸。

In East Africa the Bantu began to acquire millet and sorghum (along with the Nilo-Saharan names for those crops), and to reacquire cattle, from their Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic neighbors. They also acquired iron, which had just begun to be smelted in Africa's Sahel zone. The origins of ironworking in sub-Saharan Africa soon after 1000 B.C. are still unclear. That early date is suspiciously close to dates for the arrival of Near Eastern ironworking techniques in Carthage, on the North African coast. Hence historians often assume that knowledge of metallurgy reached sub-Saharan Africa from the north. On the other hand, copper smelting had been going on in the West African Sahara and Sahel since at least 2000 B.C. That could have been the precursor to an independent African discovery of iron metallurgy. Strengthening that hypothesis, the iron-smelting techniques of smiths in sub-Saharan Africa were so different from those of the Mediterranean as to suggest independent development: African smiths discovered how to produce high temperatures in their village furnaces and manufacture steel over 2,000 years before the Bessemer furnaces of 19th-century Europe and America.

在东非,班图人开始从他们的说尼罗-撒哈拉语和阿非罗-亚细亚语的邻居那里得到了黍和高粱(以及尼罗-撒哈拉语中表示这些作物的名称),并重新得到了牛群。他们还得到了铁,那时铁还刚刚开始在非洲的萨赫勒地带熔炼。公元前1000年后不久,非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区便已有了铁制品的制造,但起源于何处则仍不清楚。这个早期年代有可能接近于北非海岸迦太基的近东铁制品制造技术引进的年代。因此,一些历史学家常常假定冶金知识是从北面传入非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区的。另一方面,自从至少公元前2000年以后,铜的熔炼就已在西非撒哈拉地区和萨赫勒地带进行。那可能是非洲独立发现铁冶炼术的先声。非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南铁匠们的铁熔炼技术为这一假设提供了佐证,因为它们和地中海地区的铁熔炼技术差异很大,足以表明这是独立的发展:非洲的铁匠们发现如何在他们村庄的熔炉里产生高温从而炼出钢来,这比19世纪欧洲和美国的贝塞麦转炉早了2000多年。

With the addition of iron tools to their wet-climate crops, the Bantu had finally put together a military-industrial package that was unstoppable in the subequatorial Africa of the time. In East Africa they still had to compete against numerous Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic Iron Age farmers. But to the south lay 2,000 miles of country thinly occupied by Khoisan hunter-gatherers, lacking iron and crops. Within a few centuries, in one of the swiftest colonizing advances of recent prehistory, Bantu farmers had swept all the way to Natal, on the east coast of what is now South Africa.

有了适应湿润气候的作物,再加上铁器,班图人终于拼凑出一整套在当时非洲赤道以南地区所向披靡的军事-工业力量。在东非,他们仍然不得不同为数众多的说尼罗-撒哈拉语和阿非罗-亚细亚语的铁器时代的农民进行竞争。但在南部2000英里的地区内生活着科伊桑狩猎采集族群,他们不但人口稀少,而且没有铁器和作物。在几个世纪内,班图农民在最近的史前史上的一次最迅猛的移民进军中,以摧枯拉朽之势,一路推进到今天南非东海岸纳塔尔省的地方。

It's easy to oversimplify what was undoubtedly a rapid and dramatic expansion, and to picture all Khoisan in the way being trampled by onrushing Bantu hordes. In reality, things were more complicated. Khoisan peoples of southern Africa had already acquired sheep and cattle a few centuries ahead of the Bantu advance. The first Bantu pioneers probably were few in number, selected wet-forest areas suitable for their yam agriculture, and leapfrogged over drier areas, which they left to Khoisan herders and hunter-gatherers. Trading and marriage relationships were undoubtedly established between those Khoisan and the Bantu farmers, each occupying different adjacent habitats, just as Pygmy hunter-gatherers and Bantu farmers still do today in equatorial Africa. Only gradually, as the Bantu multiplied and incorporated cattle and dry-climate cereals into their economy, did they fill in the leapfrogged areas. But the eventual result was still the same: Bantu farmers occupying most of the former Khoisan realm; the legacy of those former Khoisan inhabitants reduced to clicks in scattered non-Khoisan languages, as well as buried skulls and stone tools waiting for archaeologists to discover; and the Khoisan-like appearance of some southern African Bantu peoples.

我们很容易把这种无疑是一次迅速而引人注目的扩张行动简单化,并把一路上的科伊桑人描绘成听任成群结队汹涌而来的班图人践踏的人。事实上,情况要比这复杂。非洲南部的科伊桑族群在班图人向外扩张前的几个世纪中已经有了牛、羊。班图人的第一批开路先锋可能人数很少,他们选择了适于种植他们的薯蓣的湿润的森林地区,而跳过了比较干旱的地区,把这些地区留给科伊桑的牧人和以狩猎采集为生的人。交换和通婚关系无疑已在这些科伊桑农民和班图农民之间建立起来,他们各自占据邻近的一些不同的栖息地,就像俾格米狩猎采集族群和班图农民今天在赤道非洲仍然在做的那样。随着班图人口的增长并把牛和适应干旱气候的谷物吸收进他们的经济,他们才逐步地布满了原先被跳过的那些地区。但最后的结果仍然一样:班图农民占据了原先属于科伊桑人的大部分地区;原先的这些科伊桑居民的遗产除了埋在地下等待考古学家去发现的头骨和石器外,就只剩下分散的非科伊桑语言中的吸气音;以及非洲南部某些班图族群酷似科伊桑人的外貌特征。

What actually happened to all those vanished Khoisan populations? We don't know. All we can say for sure is that, in places where Khoisan peoples had lived for perhaps tens of thousands of years, there are now Bantu. We can only venture a guess, by analogy with witnessed events in modern times when steel-toting white farmers collided with stone tool-using hunter-gatherers of Aboriginal Australia and Indian California. There, we know that hunter-gatherers were rapidly eliminated in a combination of ways: they were driven out, men were killed or enslaved, women were appropriated as wives, and both sexes became infected with epidemics of the farmers' diseases. An example of such a disease in Africa is malaria, which is borne by mosquitoes that breed around farmers' villages, and to which the invading Bantu had already developed genetic resistance but Khoisan hunter-gatherers probably had not.

这些消失了的科伊桑人究竟发生了什么事?我们不得而知。我们唯一能够肯定的是:在科伊桑族群生活了也许有几万年之久的一些地方,现在生活着班图人。我们只能大胆猜测,用现代亲眼目睹的一些事件来进行类比,例如用钢铁武装起来的白人农民与使用石器的澳大利亚土著和加利福尼亚印第安狩猎采集族群之间的冲突。在这一点上,我们知道,狩猎采集族群被用一系列互相配合的方法很快地消灭了:他们或者被赶走,或者男人被杀死或沦为奴隶,女人被霸占为妻,或者无论男女都受到农民的流行病的感染。在非洲这种病的一个例子就是疟疾,疟疾是蚊子传染的,而蚊子是在农民村庄的四周滋生的,同时,对于这种疾病,入侵的班图人已经形成了遗传的抵抗力,而科伊桑狩猎采集族群大概还没有。

However, Figure 19.1, of recent African human distributions, reminds us that the Bantu did not overrun all the Khoisan, who did survive in southern African areas unsuitable for Bantu agriculture. The southernmost Bantu people, the Xhosa, stopped at the Fish River on South Africa's south coast, 500 miles east of Cape Town. It's not that the Cape of Good Hope itself is too dry for agriculture: it is, after all, the breadbasket of modern South Africa. Instead, the Cape has a Mediterranean climate of winter rains, in which the Bantu summer-rain crops do not grow. By 1652, the year the Dutch arrived at Cape Town with their winter-rain crops of Near Eastern origin, the Xhosa had still not spread beyond the Fish River.

然而,关于最近的非洲人口分布的图19.1提醒我们,班图人并没有搞垮所有的科伊桑人,在非洲南部的一些不适合班图人农业的地区仍有科伊桑人幸存下来。最南端的班图人是科萨人,他们在开普敦以东500英里的南非南海岸的菲什河停了下来。这不是因为好望角这个地方过于干旱不适合农业:毕竟它是现代南非的粮仓啊。事实上,好望角冬天多雨,属于地中海型气候,在这个气候条件下,班图人的适应了夏雨的作物是不能生长的。到1652年,即荷兰人带着他们原产近东的适应冬雨的作物到达开普敦的那一年,科萨人仍未渡过菲什河。

That seeming detail of plant geography had enormous implications for politics today. One consequence was that, once South African whites had quickly killed or infected or driven off the Cape's Khoisan population, whites could claim correctly that they had occupied the Cape before the Bantu and thus had prior rights to it. That claim needn't be taken seriously, since the prior rights of the Cape Khoisan didn't inhibit whites from dispossessing them. The much heavier consequence was that the Dutch settlers in 1652 had to contend only with a sparse population of Khoisan herders, not with a dense population of steel-equipped Bantu farmers. When whites finally spread east to encounter the Xhosa at the Fish River in 1702, a period of desperate fighting began. Even though Europeans by then could supply troops from their secure base at the Cape, it took nine wars and 175 years for their armies, advancing at an average rate of less than one mile per year, to subdue the Xhosa. How could whites have succeeded in establishing themselves at the Cape at all, if those first few arriving Dutch ships had faced such fierce resistance?

这种植物地理学的表面上的细节对今天的政治具有重大的关系。一个后果是:一旦南非的白人迅速杀死或用疾病感染或赶走好望角的科伊桑人群体,白人就能正当地宣称他们在班图人之前占有了好望角,因而对它拥有优先权。这种宣布不必认真看待,因为好望角科伊桑人的优先权并没有能阻止白人把他们赶走。严重得多的后果是,1652年的荷兰移民必须全力对付的,是人口稀少的科伊桑牧人,而不是人口稠密的用钢铁装备起来的班图农民。当白人最后向东扩张,于1702年在菲什河与科萨人遭遇时,一场长期的殊死战斗开始了。虽然欧洲人当时能够从他们在好望角的巩固基地调派军队,但也经过了9次战争、历时175年才把科萨人征服,军队前进的速度平均每年不到一英里。如果当初那几艘最早到来的荷兰船遇到这样的激烈抵抗,白人怎能成功地在好望角站稳脚跟呢?

Thus, the problems of modern South Africa stem at least in part from a geographic accident. The homeland of the Cape Khoisan happened to contain few wild plants suitable for domestication; the Bantu happened to inherit summer-rain crops from their ancestors of 5,000 years ago; and Europeans happened to inherit winter-rain crops from their ancestors of nearly 10,000 years ago. Just as the sign “Goering Street” in the capital of newly independent Namibia reminded me, Africa's past has stamped itself deeply on Africa's present.

因此,现代南非的问题至少一部分源自地理上的偶然因素。好望角科伊桑人的家园碰巧很少有适于驯化的野生植物;班图人碰巧从他们5000年前的祖先那里继承了适应夏雨的作物;而欧洲人碰巧从他们近1万年前的祖先那里继承了适应冬雨的作物。正像新独立的纳米比亚首都的那块“戈林街”路牌提醒我的那样,非洲的过去给非洲的现在打上了深深的烙印。

THAT'S HOW THE Bantu were able to engulf the Khoisan, instead of vice versa. Now let's turn to the remaining question in our puzzle of African prehistory: why Europeans were the ones to colonize sub-Saharan Africa. That it was not the other way around is especially surprising, because Africa was the sole cradle of human evolution for millions of years, as well as perhaps the homeland of anatomically modern Homo sapiens. To these advantages of Africa's enormous head start were added those of highly diverse climates and habitats and of the world's highest human diversity. An extraterrestrial visiting Earth 10,000 years ago might have been forgiven for predicting that Europe would end up as a set of vassal states of a sub-Saharan African empire.

这就是班图人何以能够“淹没”科伊桑人,而不是相反。现在,让我们转向我们对非洲史前史的难解之谜的剩下来的一个问题:为什么欧洲人成了在非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南殖民的人。事情竟然不是反其道而行之,这尤其令人惊讶,因为非洲不但可能是解剖学上现代智人的家乡,而且也是几百万年来人类进化的唯一发源地。非洲除了巨大的领先优势这些有利条件外,还有高度多样化的气候和生境以及世界上最高度的人类多样化这些有利条件。如果1万年前有一个外星人访问地球,他认为欧洲最后会成为非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南的一个帝国的一批附庸国家,他作出这样的预测也许是情有可原的。

The proximate reasons behind the outcome of Africa's collision with Europe are clear. Just as in their encounter with Native Americans, Europeans entering Africa enjoyed the triple advantage of guns and other technology, widespread literacy, and the political organization necessary to sustain expensive programs of exploration and conquest. Those advantages manifested themselves almost as soon as the collisions started: barely four years after Vasco da Gama first reached the East African coast, in 1498, he returned with a fleet bristling with cannons to compel the surrender of East Africa's most important port, Kilwa, which controlled the Zimbabwe gold trade. But why did Europeans develop those three advantages before sub-Saharan Africans could?

导致非洲与欧洲碰撞的这一结果的直接原因是很清楚的。正如他们与印第安人遭遇时的情况一样,进入非洲的欧洲人拥有三重优势:枪炮和其他技术、普及的文化以及为维持探险和征服的花费巨大的计划所必不可少的政治组织。这些优势在碰撞几乎还刚刚开始时就显示了出来:在法斯科·达·伽马于1498年首次抵达东非海岸后仅仅4年,他又率领一支布满了大炮的舰队卷土重来,迫使控制津巴布韦黄金贸易的东非最重要的港口基尔瓦投降。但为什么欧洲人能发展出这3大优势,而撒哈拉沙漠以南的非洲人则不能呢?

As we have discussed, all three arose historically from the development of food production. But food production was delayed in sub-Saharan Africa (compared with Eurasia) by Africa's paucity of domesticable native animal and plant species, its much smaller area suitable for indigenous food production, and its north-south axis, which retarded the spread of food production and inventions. Let's examine how those factors operated.

我们已讨论过,从历史上看,所有这三者都来自粮食生产的发展。但粮食生产在非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区被延误了(与欧亚大陆相比),其原因是非洲缺少可以驯化的本地动植物物种,它的适于本地粮食生产的小得多的面积,以及它的妨碍粮食生产和发明的传播的南北轴向。让我们研究一下这些因素是如何起作用的。

First, as regards domestic animals, we've already seen that those of sub-Saharan Africa came from Eurasia, with the possible exception of a few from North Africa. As a result, domestic animals did not reach sub-Saharan Africa until thousands of years after they began to be utilized by emerging Eurasian civilizations. That's initially surprising, because we think of Africa as the continent of big wild mammals. But we saw in Chapter 9 that a wild animal, to be domesticated, must be sufficiently docile, submissive to humans, cheap to feed, and immune to diseases and must grow rapidly and breed well in captivity. Eurasia's native cows, sheep, goats, horses, and pigs were among the world's few large wild animal species to pass all those tests. Their African equivalents—such as the African buffalo, zebra, bush pig, rhino, and hippopotamus—have never been domesticated, not even in modern times.

首先,关于家畜,我们已经看到,非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区的家畜来自欧亚大陆,可能有少数几个例外是来自北非。因此,直到家畜开始被新兴的欧亚大陆文明利用之后几千年,它们才到达非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区。这在开始时的确使人感到奇怪,因为我们认为非洲是充满大型野生哺乳动物的那个大陆。但我们在第九章中看到,要想对一种野生动物进行驯化,它必须相当温驯,对人服从,驯养花费少,对一些疾病有免疫力,而且还必须生长迅速并在圈养中繁殖良好。欧亚大陆产的牛、绵羊、山羊、马和猪是世界上少数几种通过所有这些考验的大型野生动物。而它们的非洲同类——如非洲野牛、斑马、野猪、犀牛和河马——则从来没有被驯化过,甚至在现代也是如此。

It's true, of course, that some large African animals have occasionally been tamed. Hannibal enlisted tamed African elephants in his unsuccessful war against Rome, and ancient Egyptians may have tamed giraffes and other species. But none of those tamed animals was actually domesticated—that is, selectively bred in captivity and genetically modified so as to become more useful to humans. Had Africa's rhinos and hippos been domesticated and ridden, they would not only have fed armies but also have provided an unstoppable cavalry to cut through the ranks of European horsemen. Rhino-mounted Bantu shock troops could have overthrown the Roman Empire. It never happened.

当然,有些大型的非洲动物有时确曾被驯养过。汉尼拔在对罗马的不成功的战争中利用过驯服的非洲象,古代埃及人也可能驯养过长颈鹿和其他动物。但这些驯养的动物没有一种实际上被驯化了——就是说,在圈养中进行有选择的繁殖和对遗传性状的改变以使之对人类更加有用。如果非洲的犀牛和河马得到驯化并供人骑乘,它们不但可以供养军队,而且还可以组成一支所向披靡的骑兵,把欧洲的骑兵冲得落花流水。骑着犀牛的班图突击队可能已推翻了罗马帝国。但这种事决没有发生。

A second factor is a corresponding, though less extreme, disparity between sub-Saharan Africa and Eurasia in domesticable plants. The Sahel, Ethiopia, and West Africa did yield indigenous crops, but many fewer varieties than grew in Eurasia. Because of the limited variety of wild starting material suitable for plant domestication, even Africa's earliest agriculture may have begun several thousand years later than that of the Fertile Crescent.

第二个因素是非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区和欧亚大陆之间在可驯化的植物方面的一种虽然不是那样极端但也相当大的差异。萨赫勒地带、埃塞俄比亚和西非也有土生土长的作物,但在品种数量上比欧亚大陆少得多。由于适合驯化的野生起始植物品种有限,甚至非洲最早的农业也可能比新月沃地的农业晚了几千年。

Thus, as far as plant and animal domestication was concerned, the head start and high diversity lay with Eurasia, not with Africa. A third factor is that Africa's area is only about half that of Eurasia. Furthermore, only about one-third of its area falls within the sub-Saharan zone north of the equator that was occupied by farmers and herders before 1000 B.C. Today, the total population of Africa is less than 700 million, compared with 4 billion for Eurasia. But, all other things being equal, more land and more people mean more competing societies and inventions, hence a faster pace of development.

因此,就动植物的驯化而论,领先优势和高度多样性属于欧亚大陆,而不属于非洲。第三个因素是非洲的面积仅及欧亚大陆的面积的一半左右。而且,非洲面积中只有三分之一左右是在公元前1000年以前为农民和牧人所占据的赤道以北的撒哈拉沙漠以南地区。今天,非洲的总人口不到7亿,而欧亚大陆有40亿。但如果所有其他条件相等,更多的土地和更多的人口意味着更多的相互竞争的社会和更多的发明创造,因而也就意味着更快的发展速度。

The remaining factor behind Africa's slower rate of post-Pleistocene development compared with Eurasia's is the different orientation of the main axes of these continents. Like that of the Americas, Africa's major axis is north-south, whereas Eurasia's is east-west (Figure 10.1). As one moves along a north-south axis, one traverses zones differing greatly in climate, habitat, rainfall, day length, and diseases of crops and livestock. Hence, crops and animals domesticated or acquired in one part of Africa had great difficulty in moving to other parts. In contrast, crops and animals moved easily between Eurasian societies thousands of miles apart but at the same latitude and sharing similar climates and day lengths.

造成非洲在更新世后发展速度比欧亚大陆慢的其余一个因素,是这两个大陆主轴线的不同走向。非洲的主轴线和美洲的主轴线一样都是南北走向,而欧亚大陆的主轴线则是东西走向(图10.1)。如果你沿南北轴线行走,你会穿越在气候、生态环境、雨量、日长以及作物和牲口疾病都大不相同的地带。因此,在非洲某个地区驯化或得到的动物和作物很难传播到其他地区。相比之下,在虽然相隔数千英里但处于同一纬度并有相似的气候和日长的欧亚大陆各社会之间,作物和动物的传播就显得容易了。

The slow passage or complete halt of crops and livestock along Africa's north-south axis had important consequences. For example, the Mediterranean crops that became Egypt's staples require winter rains and seasonal variation in day length for their germination. Those crops were unable to spread south of the Sudan, beyond which they encountered summer rains and little or no seasonal variation in daylight. Egypt's wheat and barley never reached the Mediterranean climate at the Cape of Good Hope until European colonists brought them in 1652, and the Khoisan never developed agriculture. Similarly, the Sahel crops adapted to summer rain and to little or no seasonal variation in day length were brought by the Bantu into southern Africa but could not grow at the Cape itself, thereby halting the advance of Bantu agriculture. Bananas and other tropical Asian crops for which Africa's climate is eminently suitable, and which today are among the most productive staples of tropical African agriculture, were unable to reach Africa by land routes. They apparently did not arrive until the first millennium A.D., long after their domestication in Asia, because they had to wait for large-scale boat traffic across the Indian Ocean.

作物和牲畜沿非洲南北轴线的缓慢通过或完全停止前进,产生了重大的后果。例如,已经成为埃及的主食的地中海沿岸地区的作物,在发芽时需要冬雨和日长的季节性变化。这些作物无法传播到苏丹以南,因为过了苏丹,它们就会碰上夏雨和很少或根本没有季节性的日照变化。埃及的小麦和大麦在欧洲人于1652年把它们带来之前,一直没有到达好望角的地中海型气候区,而科伊桑人也从来没有发展过农业。同样,适应夏雨和很少或根本没有季节性的日长变化的萨赫勒地带的作物,是班图人带到非洲南部的,但在好望角却不能生长,从而终止了班图农业的前进。非洲的气候特别适合香蕉和其他的亚洲热带作物,今天这些作物已居于非洲热带农业最多产的主要作物之列,但它们却无法从陆路到达非洲。显然,直到公元第一个1千年,也就是它们在亚洲驯化后很久,它们才到达非洲,因为它们必须等到横渡印度洋的大规模船运的那个时代。

Africa's north-south axis also seriously impeded the spread of livestock. Equatorial Africa's tsetse flies, carrying trypanosomes to which native African wild mammals are resistant, proved devastating to introduced Eurasian and North African species of livestock. The cows that the Bantu acquired from the tsetse-free Sahel zone failed to survive the Bantu expansion through the equatorial forest. Although horses had already reached Egypt around 1800 B.C. and transformed North African warfare soon thereafter, they did not cross the Sahara to drive the rise of cavalry-mounted West African kingdoms until the first millennium A.D., and they never spread south through the tsetse fly zone. While cattle, sheep, and goats had already reached the northern edge of the Serengeti in the third millennium B.C., it took more than 2,000 years beyond that for livestock to cross the Serengeti and reach southern Africa.

非洲的南北轴线也严重地妨碍了牲畜的传播。赤道非洲的采采蝇是锥虫体的携带者,虽然非洲当地的野生哺乳动物对锥虫病有抵抗力,但对从欧亚大陆和北非引进的牲畜来说,这种病证明是灾难性的。班图人从没有采采蝇的萨赫勒地带获得的牛,在班图人通过赤道森林的扩张中亦未能幸免。虽然马在公元前1800年左右已经到达埃及,并在那以后不久改变了北非的战争方式,但直到公元第一个1千年中,它们才渡过撒哈拉沙漠,推动了一些以骑兵为基础的西非王国的出现,而且它们也从来没有通过采采蝇出没的地区而到达南方。虽然牛、绵羊和山羊在公元前第三个1千年中已经到达塞伦格蒂大草原的北缘,但在那以后又过了2000年,牲畜才越过塞伦格蒂到达了非洲南部。

Similarly slow in spreading down Africa's north-south axis was human technology. Pottery, recorded in the Sudan and Sahara around 8000 B.C., did not reach the Cape until around A.D. 1. Although writing developed in Egypt by 3000 B.C. and spread in an alphabetized form to the Nubian kingdom of Meroe, and although alphabetic writing reached Ethiopia (possibly from Arabia), writing did not arise independently in the rest of Africa, where it was instead brought in from the outside by Arabs and Europeans.

沿非洲南北轴线同样缓慢传播的还有人类的技术。陶器在公元前8000年左右已经在苏丹和撒哈拉地区出现,但直到公元元年才到达好望角。虽然文字不迟于公元前3000年已在埃及发明出来,并以字母形式传入努比亚的麦罗威王国,虽然字母文字也传入了埃塞俄比亚(可能从阿拉伯半岛传入),但文字并没有在非洲的其余地区独立出现,这些地区的文字是阿拉伯人和欧洲人从外面带进来的。

In short, Europe's colonization of Africa had nothing to do with differences between European and African peoples themselves, as white racists assume. Rather, it was due to accidents of geography and biogeography—in particular, to the continents' different areas, axes, and suites of wild plant and animal species. That is, the different historical trajectories of Africa and Europe stem ultimately from differences in real estate.

总之,欧洲在非洲的殖民并不像某些白人种族主义者所认为的那样与欧洲民族和非洲民族本身之间的差异有关。恰恰相反,这是由于地理学和生物地理学的偶然因素所致——特别是由于这两个大陆之间不同的面积、不同的轴线方向和不同的动植物品种所致。就是说,非洲和欧洲的不同历史发展轨迹归根到底来自它们之间的“不动产”的差异。

注释:

1. 尼日尔-刚果语系: 按照美国语言学家J·H·格林伯格的划分,应为尼日尔-科尔多凡语系中的一个语族,另一语族为科尔多凡语族。尼日尔-刚果语族为一个大语族,包括6个语支,共890种语言。——译者

2. 欧力斯里洋:古代地理学对非洲与印度之间大洋的名称,实际上包括红海与波斯湾,后仅用以称红海。——译者

3. 伽马(1460?—1524):葡萄牙航海家,首辟由欧洲绕非洲好望角到印度的航道(1497—1499),使葡萄牙得以在印度洋上建立霸权,1524年出任葡属印度总督。——译者