CHAPTER 2

第二章

A NATURAL EXPERIMENT OF HISTORY

历史的自然实验

ON THE CHATHAM ISLANDS, 500 MILES EAST OF NEW Zealand, centuries of independence came to a brutal end for the Moriori people in December 1835. On November 19 of that year, a ship carrying 500 Maori armed with guns, clubs, and axes arrived, followed on December 5 by a shipload of 400 more Maori. Groups of Maori began to walk through Moriori settlements, announcing that the Moriori were now their slaves, and killing those who objected. An organized resistance by the Moriori could still then have defeated the Maori, who were outnumbered two to one. However, the Moriori had a tradition of resolving disputes peacefully. They decided in a council meeting not to fight back but to offer peace, friendship, and a division of resources.

在新西兰以东500英里处的查塔姆群岛上,莫里奥里人的长达几个世纪的独立,于1835年在一片腥风血雨中宣告结束。那一年的11月19日,500个毛利人带着枪支、棍棒和斧头,乘坐一艘船来到了。接着在12月5日,又有一艘船运来了400个毛利人。一群群毛利人走过莫里奥里人的一个个定居点,宣布说莫里奥里人现在是他们的奴隶,并杀死那些表示反对的人。当时,如果莫里奥里人进行有组织的抵抗,是仍然可以打败毛利人的,因为毛利人在人数上以一比二处于劣势。然而,莫里奥里人具有一种和平解决争端的传统。他们在议事会上决定不进行反击,而是提出和平、友好和分享资源的建议。

Before the Moriori could deliver that offer, the Maori attacked en masse. Over the course of the next few days, they killed hundreds of Moriori, cooked and ate many of the bodies, and enslaved all the others, killing most of them too over the next few years as it suited their whim. A Moriori survivor recalled, “[The Maori] commenced to kill us like sheep…. [We] were terrified, fled to the bush, concealed ourselves in holes underground, and in any place to escape our enemies. It was of no avail; we were discovered and killed—men, women, and children indiscriminately.” A Maori conqueror explained. “We took possession…in accordance with our customs and we caught all the people. Not one escaped. Some ran away from us, these we killed, and others we killed—but what of that? It was in accordance with our custom.”

莫里奥里人还没有来得及发出那个建议,毛利人已开始了全面进攻。在以后的几天中,他们杀死了数以百计的莫里奥里人,把他们的许多尸体煮来吃,并把其余所有的人变为奴隶,在其后的几年中又把其中大多数人随心所欲地杀死。一个莫里奥里的幸存者回忆说,“(毛利人)开始杀我们,就像宰羊一样……(我们)都吓坏了,逃到灌木丛中,躲进地洞里,逃到任何可以躲避我们敌人的地方。但这都没有用;我们被发现了并被杀死——男人、女人和小孩,一古脑儿地被杀死。”一个毛利人征服者解释说,“我们占领了……是按照我们的习俗,我们还捉住了所有的人。一个也没有逃掉。也有一些从我们手中逃走的,这些人我们抓住就杀,我们还杀了其他一些人——但那又怎么样呢?这符合我们的习俗。”

The brutal outcome of this collision between the Moriori and the Maori could have been easily predicted. The Moriori were a small, isolated population of hunter-gatherers, equipped with only the simplest technology and weapons, entirely inexperienced at war, and lacking strong leadership or organization. The Maori invaders (from New Zealand's North Island) came from a dense population of farmers chronically engaged in ferocious wars, equipped with more-advanced technology and weapons, and operating under strong leadership. Of course, when the two groups finally came into contact, it was the Maori who slaughtered the Moriori, not vice versa.

莫里奥里人和毛利人之间这场冲突的残酷结果,本是不难预见的。莫里奥里人是一个很小的与世隔绝的族群,他们是以狩猎采集为生的人,他们所掌握的仅仅是最简单的技术和武器,对打仗毫无经验,也缺乏强有力的领导和组织。毛利人入侵者(来自新西兰的北岛)来自人口稠密的农民,他们长期从事残酷的战争,装备有比较先进的技术和武器,并且在强有力的领导下进行活动。当这两个群体发生接触时,当然是毛利人屠杀莫里奥里人,而不是相反。

The tragedy of the Moriori resembles many other such tragedies in both the modern and the ancient world, pitting numerous well-equipped people against few ill-equipped opponents. What makes the Maori-Moriori collision grimly illuminating is that both groups had diverged from a common origin less than a millennium earlier. Both were Polynesian peoples. The modern Maori are descendants of Polynesian farmers who colonized New Zealand around A.D. 1000. Soon thereafter, a group of those Maori in turn colonized the Chatham Islands and became the Moriori. In the centuries after the two groups separated, they evolved in opposite directions, the North Island Maori developing more-complex and the Moriori less-complex technology and political organization. The Moriori reverted to being hunter-gatherers, while the North Island Maori turned to more intensive farming.

莫里奥里人的悲剧与现代世界和古代世界的其他许多诸如此类的悲剧有相似之处,就是众多的装备优良的人去对付很少的装备低劣的对手。毛利人和莫里奥里人的这次冲突使人们了解到一个可怕事实,原来这两个群体是在不到1000年前从同一个老祖宗那里分化出来的。他们都是波利尼西亚人。现代毛利人是公元1000年左右移居新西兰的波利尼西亚农民的后代。在那以后不久,这些毛利人中又有一批移居查塔姆群岛,变成了莫里奥里人。在这两个群体分道扬镳后的几个世纪中,他们各自朝相反的方向演化,北岛毛利人发展出比较复杂的技术和政治组织,而莫里奥里人发展出来的技术和政治组织则比较简单。莫里奥里人回复到以前的狩猎采集生活,而北岛毛利人则转向更集约的农业。

Those opposite evolutionary courses sealed the outcome of their eventual collision. If we could understand the reasons for the disparate development of those two island societies, we might have a model for understanding the broader question of differing developments on the continents.

这种相反的演化道路注定了他们最后冲突的结果。如果我们能够了解这两个岛屿社会向截然不同的方向发展的原因,我们也许就有了一个模式,用以了解各个大陆不同发展的更广泛的问题。

MORIORI AND MAORI history constitutes a brief, small-scale natural experiment that tests how environments affect human societies. Before you read a whole book examining environmental effects on a very large scale—effects on human societies around the world for the last 13,000 years—you might reasonably want assurance, from smaller tests, that such effects really are significant. If you were a laboratory scientist studying rats, you might perform such a test by taking one rat colony, distributing groups of those ancestral rats among many cages with differing environments, and coming back many rat generations later to see what had happened. Of course, such purposeful experiments cannot be carried out on human societies. Instead, scientists must look for “natural experiments,” in which something similar befell humans in the past.

莫里奥里人和毛利人的历史构成了一个短暂的小规模的自然实验,用以测试环境影响人类社会的程度。在你阅读整整一本书来研究大范围内的环境影响——过去13000年中环境对全世界人类社会的影响——之前,你也许有理由希望通过较小的试验来使自己确信这种影响确实是意义重大的。如果你是一个研究老鼠的实验科学家,你可能会做这样的实验:选择一个老鼠群体,把这些祖代老鼠分成若干组,分别关在具有不同环境的笼子里,等这些老鼠传下许多代之后再回来看看发生了什么情况。当然,这种有目的的实验不可能用于人类社会。科学家只能去寻找“自然实验”,因为根据这种实验,人类在过去也碰到了类似情况。

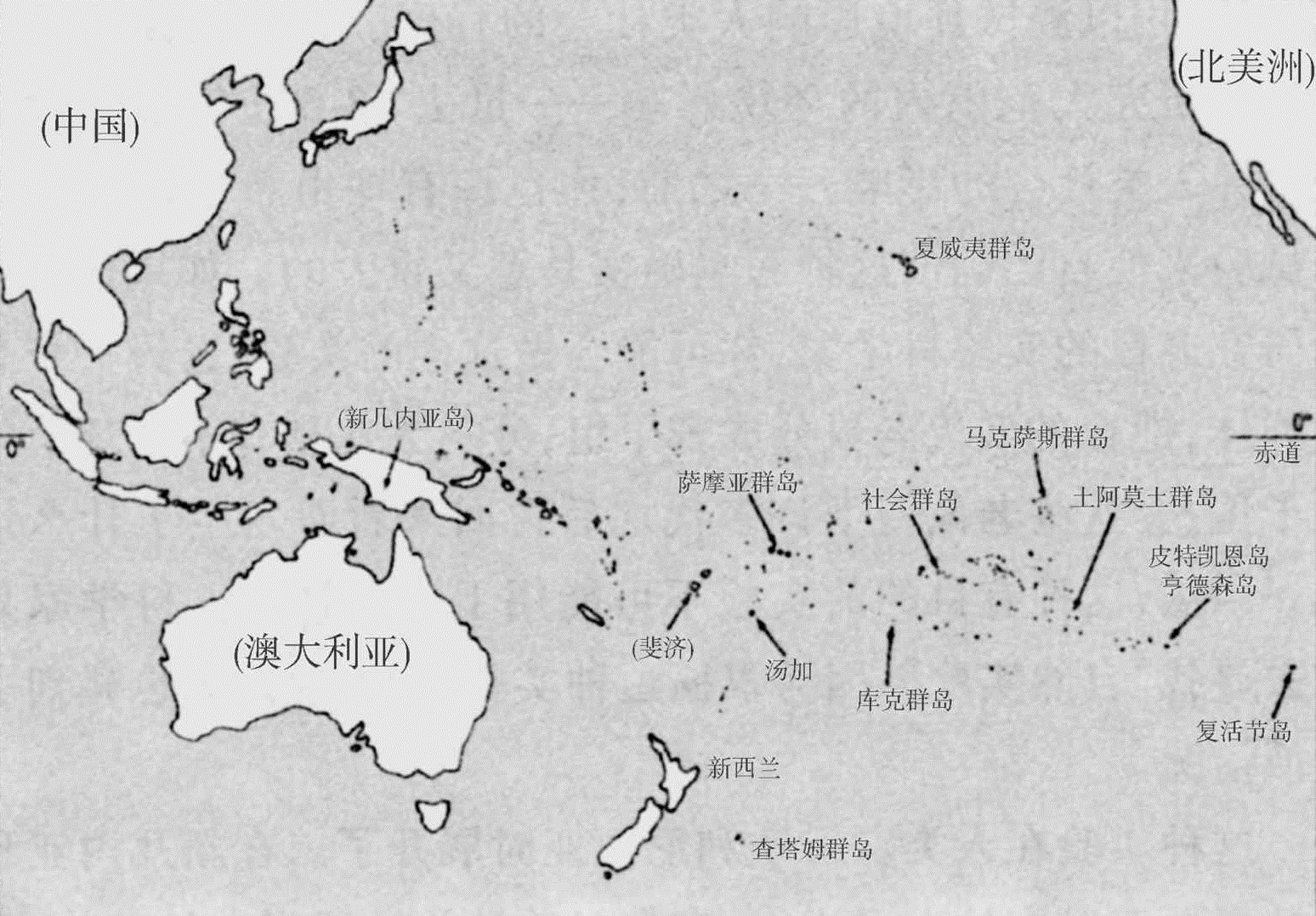

Such an experiment unfolded during the settlement of Polynesia. Scattered over the Pacific Ocean beyond New Guinea and Melanesia are thousands of islands differing greatly in area, isolation, elevation, climate, productivity, and geological and biological resources (Figure 2.1). For most of human history those islands lay far beyond the reach of watercraft. Around 1200 B.C. a group of farming, fishing, seafaring people from the Bismarck Archipelago north of New Guinea finally succeeded in reaching some of those islands. Over the following centuries their descendants colonized virtually every habitable scrap of land in the Pacific. The process was mostly complete by A.D. 500, with the last few islands settled around or soon after A.D. 1000.

这种实验在人类定居波利尼西亚时展开了。在新几内亚和美拉尼西亚以东的太平洋上,有数以千计的星罗棋布的岛屿,它们在面积、孤立程度、高度、气候、生产力以及地质和生物资源方面都大不相同(图2.1)。在人类历史的大部分时间里,这些岛屿都是水运工具无法到达的地方。公元前1200年左右,一批来自新几内亚北面俾斯麦群岛的,从事农业、捕鱼和航海的人,终于成功地到达了其中的一些岛屿。在随后的几百年中,他们的子孙几乎已移居到太平洋中每一小块可以住人的陆地上来。这个过程大都在公元500年时完成,最后几个岛大约在公元1000年或其后不久有人定居。

Thus, within a modest time span, enormously diverse island environments were settled by colonists all of whom stemmed from the same founding population. The ultimate ancestors of all modern Polynesian populations shared essentially the same culture, language, technology, and set of domesticated plants and animals. Hence Polynesian history constitutes a natural experiment allowing us to study human adaptation, devoid of the usual complications of multiple waves of disparate colonists that often frustrate our attempts to understand adaptation elsewhere in the world.

这样,就在一个不太长的时间内,存在巨大差异的各种岛屿环境中都有人定居下来,所有这些人都是同一群开山鼻祖的子孙后代。所有现代波利尼西亚人的最初祖先基本上都具有同样的文化、语言、技术和一批驯化的动植物。因此,波利尼西亚人的历史构成了一种自然实验,使我们能够研究人类的适应性问题,而不致由于不同移民的多次人口骤增所引起的常有的复杂情况而使我们无法去了解世界其他地方人类的适应作用。

Figure 2.1. Polynesian islands. (Parentheses denote some non- Polynesian lands.)

图2.1波利尼西亚群岛。(括弧表示某些非波利尼西亚的土地。)

Within that medium-sized test, the fate of the Moriori forms a smaller test. It is easy to trace how the differing environments of the Chatham Islands and of New Zealand molded the Moriori and the Maori differently. While those ancestral Maori who first colonized the Chathams may have been farmers, Maori tropical crops could not grow in the Chathams' cold climate, and the colonists had no alternative except to revert to being hunter-gatherers. Since as hunter-gatherers they did not produce crop surpluses available for redistribution or storage, they could not support and feed nonhunting craft specialists, armies, bureaucrats, and chiefs. Their prey were seals, shellfish, nesting seabirds, and fish that could be captured by hand or with clubs and required no more elaborate technology. In addition, the Chathams are relatively small and remote islands, capable of supporting a total population of only about 2,000 hunter-gatherers. With no other accessible islands to colonize, the Moriori had to remain in the Chathams, and to learn how to get along with each other. They did so by renouncing war, and they reduced potential conflicts from overpopulation by castrating some male infants. The result was a small, unwarlike population with simple technology and weapons, and without strong leadership or organization.

在这个中等规模的试验内,莫里奥里人的命运又构成了一个更小的试验。要追溯查塔姆群岛和新西兰的不同环境是如何不同地塑造了莫里奥里人和毛利人的,这容易做到。虽然最早在查塔姆群岛移民的毛利人祖先可能都是农民,但毛利人的热带作物不可能在查塔姆群岛的寒冷气候下生长,所以那些移民别无它法,只得重新回到狩猎采集生活。由于他们以狩猎采集为生,他们不能生产多余的农作物供重新分配和贮藏之用,所以他们无法养活不事狩猎的专门手艺人、军队、行政官员和首领。他们的猎物有海豹、有壳水生动物、巢居海鸟和鱼,这些猎物可以用手或棍棒来捕捉,不需要更复杂的技术。此外,查塔姆群岛都是一些比较小、比较偏远的岛屿,能够养活的总人口只有2000个左右的以狩猎采集为生的人。由于没有其他可以到达的岛屿用来移民,这些莫里奥里人只得留在查塔姆群岛,学会彼此和睦相处。他们通过宣布放弃战争来做到这一点,他们还通过阉割一些男婴来减少人口过剩的潜在冲突。其结果是出现了一个小小的不好战的群体,他们的技术和武器简单粗陋,他们也没有强有力的领导和组织。

In contrast, the northern (warmer) part of New Zealand, by far the largest island group in Polynesia, was suitable for Polynesian agriculture. Those Maori who remained in New Zealand increased in numbers until there were more than 100,000 of them. They developed locally dense populations chronically engaged in ferocious wars with neighboring populations. With the crop surpluses that they could grow and store, they fed craft specialists, chiefs, and part-time soldiers. They needed and developed varied tools for growing their crops, fighting, and making art. They erected elaborate ceremonial buildings and prodigious numbers of forts.

相比之下,新西兰的北部(比较温暖)是波利尼西亚的最大岛群,适宜于波利尼西亚的农业。留在新西兰的那些毛利人人数增加了,直到超过10万人。他们在局部地区形成了密集的人口,这些人长期从事与邻近居民的残酷战争。由于他们栽种的农作物有剩余并可用来贮藏,他们养活了一些专门的手艺人、首领和兼职士兵。他们需要并制作了各种各样的工具,有的用来栽种农作物,有的用来打仗,还有的用来搞艺术创作。他们建造了精致的用作举行仪式的建筑物和为数众多的城堡。

Thus, Moriori and Maori societies developed from the same ancestral society, but along very different lines. The resulting two societies lost awareness even of each other's existence and did not come into contact again for many centuries, perhaps for as long as 500 years. Finally, an Australian seal-hunting ship visiting the Chathams en route to New Zealand brought the news to New Zealand of islands where “there is an abundance of sea and shellfish; the lakes swarm with eels; and it is a land of the karaka berry…. The inhabitants are very numerous, but they do not understand how to fight, and have no weapons.” That news was enough to induce 900 Maori to sail to the Chathams. The outcome clearly illustrates how environments can affect economy, technology, political organization, and fighting skills within a short time.

就这样,莫里奥里人和毛利人由同一个祖先发展出来,但沿着十分不同的路线。由此产生的两个社会甚至不知道彼此的存在,他们在许多世纪中,也许长达500年之久再也没有接触过。最后,一艘海豹捕猎船在前往新西兰途中到过查塔姆群岛,它给新西兰带来了关于这个群岛的消息,那里“有大量的海鱼和有壳水生动物;湖里到处是鳗鱼;它是喀拉喀浆果之乡……那里居民众多,但他们不懂打仗,所以没有武器。”这个消息足以诱使900个毛利人乘船前往查塔姆群岛。这个结果清楚地表明了环境在很短时间内能在多大程度上影响经济、技术、政治组织和战斗技巧。

AS I ALREADY mentioned, the Maori-Moriori collision represents a small test within a medium-sized test. What can we learn from all of Polynesia about environmental influences on human societies? What differences among societies on different Polynesian islands need to be explained?

我已经提到,毛利人和莫里奥里人的冲突代表一个中等规模的试验内的一个小试验。关于环境对人类社会的影响问题,我们能够从整个波利尼西亚学到些什么?关于波利尼西亚不同岛屿上的一些社会之间的差异,有哪些是需要予以解释的?

Polynesia as a whole presented a much wider range of environmental conditions than did just New Zealand and the Chathams, although the latter define one extreme (the simple end) of Polynesian organization. In their subsistence modes, Polynesians ranged from the hunter-gatherers of the Chathams, through slash-and-burn farmers, to practitioners of intensive food production living at some of the highest population densities of any human societies. Polynesian food producers variously intensified production of pigs, dogs, and chickens. They organized work forces to construct large irrigation systems for agriculture and to enclose large ponds for fish production. The economic basis of Polynesian societies consisted of more or less self-sufficient households, but some islands also supported guilds of hereditary part-time craft specialists. In social organization, Polynesian societies ran the gamut from fairly egalitarian village societies to some of the most stratified societies in the world, with many hierarchically ranked lineages and with chief and commoner classes whose members married within their own class. In political organization, Polynesian islands ranged from landscapes divided into independent tribal or village units, up to multi-island proto-empires that devoted standing military establishments to invasions of other islands and wars of conquest. Finally, Polynesian material culture varied from the production of no more than personal utensils to the construction of monumental stone architecture. How can all that variation be explained?

从整体来看,波利尼西亚在环境状况方面显得比新西兰和查塔姆群岛范围广泛得多,虽然后者为波利尼西亚人的组织规定了一个极端(单纯目的)。波利尼西亚人的生存方式从查塔姆群岛上以狩猎采集为生的人,到刀耕火种的农民,到生活在不管哪种人类社会都算得上人口密度最高的某些地区从事集约型粮食生产的人。波利尼西亚的粮食生产者在不同的时间里加强对猪、狗和鸡的饲养。他们组织劳动力去建设大型农业灌溉系统,围筑很大的池塘去养鱼。波利尼西亚社会的经济基础由或多或少自给自足的家庭构成,但有些岛上还扶持一些由兼职世袭的专门手艺人组成的行会。在社会组织方面,波利尼西亚人的社会范围很广,从相当平等的村落社会到某些属于世界上等级最严格的社会,无所不有。这后一种社会有许多按等级排列的家族,还有首领阶级和平民阶级,这些阶级的成员只在自己阶级的内部通婚。在政治组织方面,波利尼西亚群岛从划分为部落单位或村落单位的一个个地区,直到一些由多个岛屿组成的原型帝国,也无所不有。这些原型帝国建有常备军事机构,专门用来对付其他岛屿的入侵和用来进行征服战争。最后,至于波利尼西亚的物质文化,从只能生产个人用具到建造纪念性的石头建筑,情况也各不相同。对于所有这些差异又应怎样解释呢?

Contributing to these differences among Polynesian societies were at least six sets of environmental variables among Polynesian islands: island climate, geological type, marine resources, area, terrain fragmentation, and isolation. Let's examine the ranges of these factors, before considering their specific consequences for Polynesian societies.

在波利尼西亚群岛之间,至少有6种环境可变因素促成了波利尼西亚社会之间的这些差异:岛屿气候、地质类型、海洋资源、面积、地形的破碎和隔离程度。让我们逐一研究这些因素,然后再考虑它们对波利尼西亚社会的具体影响。

The climate in Polynesia varies from warm tropical or subtropical on most islands, which lie near the equator, to temperate on most of New Zealand, and cold subantarctic on the Chathams and the southern part of New Zealand's South Island. Hawaii's Big Island, though lying well within the Tropic of Cancer, has mountains high enough to support alpine habitats and receive occasional snowfalls. Rainfall varies from the highest recorded on Earth (in New Zealand's Fjordland and Hawaii's Alakai Swamp on Kauai) to only one-tenth as much on islands so dry that they are marginal for agriculture.

波利尼西亚从靠近赤道的大多数岛屿上热带或亚热带的温暖,到新西兰大部分地区的不冷不热,以及查塔姆群岛和新西兰南岛南部地区的亚南极的寒冷,各种气候都有。夏威夷的大岛虽然地处北回归线以内,但也有高山,足以维持一些高山栖息地,山上偶尔也会降雪。雨量也因地而异,有些地方雨量创世界最高纪录(在新西兰的峡湾地和夏威夷考爱岛上阿拉凯沼泽),有些岛上雨量只有上面的十分之一,这些地方干旱得只能勉强发展农业。

Island geological types include coral atolls, raised limestone, volcanic islands, pieces of continents, and mixtures of those types. At one extreme, innumerable islets, such as those of the Tuamotu Archipelago, are flat, low atolls barely rising above sea level. Other former atolls, such as Henderson and Rennell, have been lifted far above sea level to constitute raised limestone islands. Both of those atoll types present problems to human settlers, because they consist entirely of limestone without other stones, have only very thin soil, and lack permanent fresh water. At the opposite extreme, the largest Polynesian island, New Zealand, is an old, geologically diverse, continental fragment of Gondwanaland, offering a range of mineral resources, including commercially exploitable iron, coal, gold, and jade. Most other large Polynesian islands are volcanoes that rose from the sea, have never formed parts of a continent, and may or may not include areas of raised limestone. While lacking New Zealand's geological richness, the oceanic volcanic islands at least are an improvement over atolls (from the Polynesians' perspective) in that they offer diverse types of volcanic stones, some of which are highly suitable for making stone tools.

岛屿地质类型包括环状珊瑚岛、隆起的石灰岩、火山岛、陆地碎块,以及这些类型的混合类型。在一个极端,无数的小岛,如土阿莫土群岛中的那些岛屿,是一些刚刚露出海面的低平环状珊瑚岛。还有一些更早的环状珊瑚岛,如亨德森岛和伦纳尔岛,已经大大高出海面,形成了隆起的石灰岩岛。这两种类型的环状珊瑚岛使人类移居碰到了难题,因为它们完全由石灰岩构成,没有其他石头,只有薄薄的一层土壤,也没有长年不竭的淡水。在另一极端,波利尼西亚最大的岛屿是新西兰,它是一个从冈瓦纳大陆[1]分离出来的古老的、具有地质多样性的陆块,上面有一系列矿物资源,包括可作商业开发的铁、煤、黄金和玉石。波利尼西亚的其他大多数大岛都是高出海面的火山,从来不是陆地的一部分,它们可能包括也可能不包括隆起的石灰岩地区。这些海洋火山岛虽然不具备新西兰的那种丰富多样的地质条件,但至少(从波利尼西亚人的观点看)要比那些环状珊瑚岛稍胜一筹,因为它们提供了多种多样的火山石,其中有些非常适于打制石器。

The volcanic islands differ among themselves. The elevations of the higher ones generate rain in the mountains, so the islands are heavily weathered and have deep soils and permanent streams. That is true, for instance, of the Societies, Samoa, the Marquesas, and especially Hawaii, the Polynesian archipelago with the highest mountains. Among the lower islands, Tonga and (to a lesser extent) Easter also have rich soil because of volcanic ashfalls, but they lack Hawaii's large streams.

这些火山岛本身也各不相同。较高火山岛的海拔高度给山地带来了雨水,所以这些岛屿受到风雨的严重侵蚀,有很厚的土壤和长年不竭的溪流。例如,社会群岛、萨摩亚群岛、马克萨斯群岛,尤其是夏威夷群岛,情况都是如此,因为它们在波利尼西亚群岛中是山势最高的。在较低的岛屿中,汤加群岛和(在较小程度上的)复活节岛由于火山灰的缘故土壤也很肥沃,但它们没有夏威夷群岛上的那种大溪流。

As for marine resources, most Polynesian islands are surrounded by shallow water and reefs, and many also encompass lagoons. Those environments teem with fish and shellfish. However, the rocky coasts of Easter, Pitcairn, and the Marquesas, and the steeply dropping ocean bottom and absence of coral reefs around those islands, are much less productive of seafood.

至于海洋资源,波利尼西亚群岛中的大多数岛屿都由浅水和礁石包围着,有许多上面还有泻湖。这里盛产鱼和有壳水生动物。然而,复活节岛、皮特凯恩岛和马克萨斯群岛的多岩石海岸和陡峭直下的洋底以及周围缺少珊瑚礁,使这里的海产少得多。

Area is another obvious variable, ranging from the 100 acres of Anuta, the smallest permanently inhabited isolated Polynesian island, up to the 103,000 square miles of the minicontinent of New Zealand. The habitable terrain of some islands, notably the Marquesas, is fragmented into steep-walled valleys by ridges, while other islands, such as Tonga and Easter, consist of gently rolling terrain presenting no obstacles to travel and communication.

面积是另一个明显的可变因素,从只有100英亩的阿努塔这个有永久性居民的与世隔绝的波利尼西亚最小岛屿,一直到103000平方英里的新西兰这个微型大陆,各种大小应有尽有。有些岛上可以住人的地带被山脊分隔成一些四面围着悬崖峭壁的山谷,其中以马克萨斯群岛最为显著,而另一些岛,如汤加群岛和复活节岛,则是由起伏平缓的地形构成,对行走往来不造成任何障碍。

The last environmental variable to consider is isolation. Easter Island and the Chathams are small and so remote from other islands that, once they were initially colonized, the societies thus founded developed in total isolation from the rest of the world. New Zealand, Hawaii, and the Marquesas are also very remote, but at least the latter two apparently did have some further contact with other archipelagoes after the first colonization, and all three consist of many islands close enough to each other for regular contact between islands of the same archipelago. Most other Polynesian islands were in more or less regular contact with other islands. In particular, the Tongan Archipelago lies close enough to the Fijian, Samoan, and Wallis Archipelagoes to have permitted regular voyaging between archipelagoes, and eventually to permit Tongans to undertake the conquest of Fiji.

最后一个需要予以考虑的环境可变因素是隔离程度。复活节岛和查塔姆群岛面积很小,同其他岛屿又相距甚远,一旦开始有了移民,则那里所建立的社会就只能在与世界其余地区完全隔绝的状态下发展。新西兰、夏威夷和马克萨斯群岛也很偏远,但后两者在首次有了移民后确曾与其他群岛有过某种进一步的接触,而所有这三者又都是由许多岛屿组成,这些岛屿相距很近,有利于同一个群岛中各个岛屿之间的经常接触。波利尼西亚其他岛屿中的大多数与其他岛屿保持着或多或少的经常接触。尤其是,汤加群岛与斐济群岛、萨摩亚群岛和瓦利斯群岛咫尺相望,使各群岛之间可以定期航行,并最终使汤加征服了斐济。

AFTER THAT BRIEF look at Polynesia's varying environments, let's now see how that variation influenced Polynesian societies. Subsistence is a convenient facet of society with which to start, since it in turn affected other facets.

在简短地考察了波利尼西亚各种不同的环境之后,现在让我们看一看这些不同是怎样影响波利尼西亚的社会的。生存是社会赖以产生的一个再恰当不过的方面,因为这个方面反过来又影响其他方面。

Polynesian subsistence depended on varying mixes of fishing, gathering wild plants and marine shellfish and Crustacea, hunting terrestrial birds and breeding seabirds, and food production. Most Polynesian islands originally supported big flightless birds that had evolved in the absence of predators, New Zealand's moas and Hawaii's flightless geese being the best-known examples. While those birds were important food sources for the initial colonists, especially on New Zealand's South Island, most of them were soon exterminated on all islands, because they were easy to hunt down. Breeding seabirds were also quickly reduced in number but continued to be important food sources on some islands. Marine resources were significant on most islands but least so on Easter, Pitcairn, and the Marquesas, where people as a result were especially dependent on food that they themselves produced.

波利尼西亚人赖以生存的手段五花八门:捕鱼、采集野生植物、捕捞海洋有壳动物和甲壳动物、猎捕陆栖鸟和繁殖季节的海鸟,以及生产粮食。波利尼西亚大多数岛屿原来都有一些大型的不会飞的鸟,它们是在没有食肉动物的情况下演化出来的,新西兰的恐鸟和夏威夷的不会飞的野鹅就是这方面最著名的例子。虽然这些鸟是最早移民的重要的食物来源,在新西兰的南岛上尤其如此,但其中大多数在所有岛屿上很快灭绝了,因为它们很容易被追捕到。繁殖季节的海鸟数目也很快减少,但在有些岛上,它们仍然是重要的食物来源。海洋资源对大多数岛屿来说都是意义重大的,但对复活节岛、皮特凯恩群岛和马克萨斯群岛来说却最不重要,因为那里的人主要依靠自己生产的食物为生。

Ancestral Polynesians brought with them three domesticated animals (the pig, chicken, and dog) and domesticated no other animals within Polynesia. Many islands retained all three of those species, but the more isolated Polynesian islands lacked one or more of them, either because livestock brought in canoes failed to survive the colonists' long overwater journey or because livestock that died out could not be readily obtained again from the outside. For instance, isolated New Zealand ended up with only dogs; Easter and Tikopia, with only chickens. Without access to coral reefs or productive shallow waters, and with their terrestrial birds quickly exterminated, Easter Islanders turned to constructing chicken houses for intensive poultry farming.

波利尼西亚人的祖先曾带来3种驯化动物(猪、鸡和狗),从那以后,在波利尼西亚范围内就再也没有驯养过任何其他动物。许多岛上仍然饲养着所有这3种动物,但那些比较孤立的波利尼西亚岛屿总要缺少一两种,这或许是由于用独木舟运送的家畜在移民的长时间的水上航行中没能存活下来,或许是由于家畜在岛上灭绝后无法迅速从外面得到补充。例如,与世隔绝的新西兰最后只剩下了狗;复活节岛和提科皮亚岛只剩下了鸡。由于无法到达珊瑚礁或海产丰富的浅水区,同时也由于陆栖鸟迅速灭绝,复活节岛上的居民转而建造鸡舍,进行集约化的家禽饲养。

At best, however, these three domesticated animal species provided only occasional meals. Polynesian food production depended mainly on agriculture, which was impossible at subantarctic latitudes because all Polynesian crops were tropical ones initially domesticated outside Polynesia and brought in by colonists. The settlers of the Chathams and the cold southern part of New Zealand's South Island were thus forced to abandon the farming legacy developed by their ancestors over the previous thousands of years, and to become hunter-gatherers again.

然而,这3种驯养的动物最多也只能供人们偶尔吃上几顿。波利尼西亚人的食物生产主要依靠农业,而在亚南极纬度地区是不可能有农业的,因为波利尼西亚的所有作物都是热带作物,当初在波利尼西亚以外的地方驯化,后来被移民带了进来。查塔姆群岛和新西兰南岛寒冷的南部地区的移民,因此不得不放弃他们的祖先在过去几千年中发展起来的农业遗产而再次成为以狩猎采集为生的人。

People on the remaining Polynesian islands did practice agriculture based on dryland crops (especially taro, yams, and sweet potatoes), irrigated crops (mainly taro), and tree crops (such as breadfruit, bananas, and coconuts). The productivity and relative importance of those crop types varied considerably on different islands, depending on their environments. Human population densities were lowest on Henderson, Rennell, and the atolls because of their poor soil and limited fresh water. Densities were also low on temperate New Zealand, which was too cool for some Polynesian crops. Polynesians on these and some other islands practiced a nonintensive type of shifting, slash-and-burn agriculture.

波利尼西亚其余岛屿上的人也从事农业,主要是旱地作物(特别是芋艿、薯蓣和甘薯)、灌溉作物(主要是芋艿)和木本作物(如面包果、香蕉和椰子)。这几种作物的产量及其相对重要性在不同的岛上是相当不同的,这是由环境决定的。人口密度在亨德森岛、伦纳尔岛和环状珊瑚岛上是最低的,因为那里土壤贫瘠,淡水有限。在气候温和的新西兰,人口密度也很低,因为那里对某些波利尼西亚作物来说过于寒冷。这些岛上和其他一些岛上的波利尼西亚人,从事一种非集约型的、轮垦的、刀耕火种的农业。

Other islands had rich soils but were not high enough to have large permanent streams and hence irrigation. Inhabitants of those islands developed intensive dryland agriculture requiring a heavy input of labor to build terraces, carry out mulching, rotate crops, reduce or eliminate fallow periods, and maintain tree plantations. Dryland agriculture became especially productive on Easter, tiny Anuta, and flat and low Tonga, where Polynesians devoted most of the land area to the growing of food.

其他一些岛屿虽然土壤肥沃,但因高度不够而没有长年不竭的大溪流,因此也就没有灌溉之利。这些岛上的居民发展了集约型的旱地农业,这需要投入很大的劳动力来修筑梯田,用覆盖料覆盖地面,进行轮作,减少或取消休耕期,以及养护林场。旱地农业在复活节岛、小小的阿努塔岛和低平的汤加岛尤其多产,这些地方的波利尼西亚人把他们的大部分土地专门用来种植粮食作物。

The most productive Polynesian agriculture was taro cultivation in irrigated fields. Among the more populous tropical islands, that option was ruled out for Tonga by its low elevation and hence its lack of rivers. Irrigation agriculture reached its peak on the westernmost Hawaiian islands of Kauai, Oahu, and Molokai, which were big and wet enough to support not only large permanent streams but also large human populations available for construction projects. Hawaiian labor corvées built elaborate irrigation systems for taro fields yielding up to 24 tons per acre, the highest crop yields in all of Polynesia. Those yields in turn supported intensive pig production. Hawaii was also unique within Polynesia in using mass labor for aquaculture, by constructing large fishponds in which milkfish and mullet were grown.

波利尼西亚的最多产农业是在水浇地里种植芋艿。在人口较多的热带岛屿中,汤加因其海拔低从而缺少河流而排除了这一选择。在夏威夷群岛最西端的考爱岛、瓦胡岛和莫洛凯岛,灌溉农业达到了顶峰,因为这些岛屿面积较大而又潮湿,不但有长年不竭的大溪流,而且还有可以用来从事建筑工程的众多人口。夏威夷用强征劳动力修建了浇灌芋艿田的复杂的灌溉系统,使每英亩芋艿产量达到24吨,是整个波利尼西亚农作物的最高产量。这些产量反过来又支援了集约型的养猪事业。在利用大规模劳动从事水产养殖方面,夏威夷在波利尼西亚群岛中也是独一无二的,那就是它修建了一些大型鱼塘来放养遮目鱼和缁鱼。

AS A RESULT of all this environmentally related variation in subsistence, human population densities (measured in people per square mile of arable land) varied greatly over Polynesia. At the lower end were the hunter-gatherers of the Chathams (only 5 people per square mile) and of New Zealand's South Island, and the farmers of the rest of New Zealand (28 people per square mile). In contrast, many islands with intensive agriculture attained population densities exceeding 120 per square mile. Tonga, Samoa, and the Societies achieved 210–250 people per square mile and Hawaii 300. The upper extreme of 1,100 people per square mile was reached on the high island of Anuta, whose population converted essentially all the land to intensive food production, thereby crammed 160 people into the island's 100 acres, and joined the ranks of the densest self-sufficient populations in the world. Anuta's population density exceeded that of modern Holland and even rivaled that of Bangladesh.

由于在生存方面所有这些与环境有关的差异,人口密度(按每平方英里可耕地上的人数来测算)在整个波利尼西亚也差异很大。人口密度低的是查塔姆群岛(每平方英里仅5人)和新西兰南岛上以狩猎采集为生的人,还有新西兰其余地区的农民(每平方英里28人)。相形之下,许多从事集约型农业的岛屿的人口密度则超过每平方英里120人。汤加、萨摩亚和社会群岛达到每平方英里210—250人,夏威夷则达到每平方英里300人。阿努塔这个高地岛则达到了人口密度的另一极端,即每平方英里1100人,岛上的人把所有陆地都改作集约型粮食生产之用,从而在这个岛的100英亩土地上挤进了160个人,使自己跻身于世界上密度最大的自给自足的人口之列。阿努塔的人口密度超过了现代荷兰,甚至和孟加拉国不相上下。

Population size is the product of population density (people per square mile) and area (square miles). The relevant area is not the area of an island but that of a political unit, which could be either larger or smaller than a single island. On the one hand, islands near one another might become combined into a single political unit. On the other hand, single large rugged islands were divided into many independent political units. Hence the area of the political unit varied not only with an island's area but also with its fragmentation and isolation.

人口的多少是人口密度(每平方英里的人数)和面积(平方英里)的乘积。相关的面积并不就是一个岛的面积,而是一个行政单位的面积,这个单位可以大于也可以小于一个岛。一方面,一些彼此靠近的岛可以组成一个行政单位。另一方面,一个高低不平的大岛则分成许多个独立的行政单位。因此,行政单位的面积不但因一个岛的面积大小而异,而且也会因该岛的地形破碎和隔离程度而有所不同。

For small isolated islands without strong barriers to internal communication, the entire island constituted the political unit—as in the case of Anuta, with its 160 people. Many larger islands never did become unified politically, whether because the population consisted of dispersed bands of only a few dozen hunter-gatherers each (the Chathams and New Zealand's southern South Island), or of farmers scattered over large distances (the rest of New Zealand), or of farmers living in dense populations but in rugged terrain precluding political unification. For example, people in neighboring steep-sided valleys of the Marquesas communicated with each other mainly by sea; each valley formed an independent political entity of a few thousand inhabitants, and most individual large Marquesan islands remained divided into many such entities.

对于一些孤立的小岛来说,如果不存在影响岛内交往的巨大障碍,那么整个岛就是一个行政单位——例如有160人的阿努塔岛。有许多较大的岛在行政上却从来没有统一过,这是否是因为这些岛上的人口组成或是每群只有几十人的一群群分散的以狩猎采集为生的人(查塔姆群岛和新西兰南岛的南部),或是相距甚远、分散居住的农民(新西兰的其余地区),或是生活在人口密集但无法实现行政统一的崎岖不平地区的农民。例如,在邻近的马克萨斯群岛上四面峭壁的山谷中生活的人要通过海路来互相交往;每个山谷就是一个由几千居民组成的独立的行政实体,而马克萨斯群岛中大多数单独的大岛仍然分成许多这样的实体。

The terrains of the Tongan, Samoan, Society, and Hawaiian islands did permit political unification within islands, yielding political units of 10,000 people or more (over 30,000 on the large Hawaiian islands). The distances between islands of the Tongan archipelago, as well as the distances between Tonga and neighboring archipelagoes, were sufficiently modest that a multi-island empire encompassing 40,000 people was eventually established. Thus, Polynesian political units ranged in size from a few dozen to 40,000 people.

汤加群岛、萨摩亚群岛、社会群岛和夏威夷群岛的地形使岛内得以实现行政统一,产生了由1万人或更多人(在夏威夷群岛中的一些大岛上超过3万人)组成的行政单位。汤加群岛中各岛之间的距离,以及汤加群岛与邻近群岛之间的距离,都不算太大,所以能够最后建立了一个包含4万人的多岛帝国。这样,波利尼西亚的行政单位从几十个人到4万人,各种大小都有。

A political unit's population size interacted with its population density to influence Polynesian technology and economic, social, and political organization. In general, the larger the size and the higher the density, the more complex and specialized were the technology and organization, for reasons that we shall examine in detail in later chapters. Briefly, at high population densities only a portion of the people came to be farmers, but they were mobilized to devote themselves to intensive food production, thereby yielding surpluses to feed nonproducers. The nonproducers mobilizing them included chiefs, priests, bureaucrats, and warriors. The biggest political units could assemble large labor forces to construct irrigation systems and fishponds that intensified food production even further. These developments were especially apparent on Tonga, Samoa, and the Societies, all of which were fertile, densely populated, and moderately large by Polynesian standards. The trends reached their zenith on the Hawaiian Archipelago, consisting of the largest tropical Polynesian islands, where high population densities and large land areas meant that very large labor forces were potentially available to individual chiefs.

一个行政单位人口的多少,与其影响波利尼西亚人的技术及经济、社会和政治组织的人口密度互相作用。一般地说,人口越多,人口密度越高,技术和组织就越复杂,专业程度就越高,其原因我们将在以后的几章里详细研究。简言之,人口密度高时,只有一部分人最后成为农民,但他们被调动起来去专门从事集约型的粮食生产,从而生产出剩余粮食去养活非生产者。能够调动农民的非生产者包括首领、神职人员、官员和战士。最大的行政单位能够调集大批劳动力来修建进一步加强粮食生产的灌溉系统和鱼塘。这方面的发展在汤加、萨摩亚和社会群岛尤其明显,因为这些地方土壤肥沃,人口稠密,而且按照波利尼西亚的标准也有适当大小的面积。这种趋势在夏威夷群岛发展到了顶点,这个群岛包括波利尼西亚最大的热带岛屿,那里人口密度高,土地面积大,这就意味着有很大一批劳动力可能供各个首领驱使。

The variations among Polynesian societies associated with different population densities and sizes were as follows. Economies remained simplest on islands with low population densities (such as the hunter-gatherers of the Chathams), low population numbers (small atolls), or both low densities and low numbers. In those societies each household made what it needed; there was little or no economic specialization. Specialization increased on larger, more densely populated islands, reaching a peak on Samoa, the Societies, and especially Tonga and Hawaii. The latter two islands supported hereditary part-time craft specialists, including canoe builders, navigators, stone masons, bird catchers, and tattooers.

在波利尼西亚社会中,与不同的人口密度和人口多少相联系的差异有以下几个方面。在人口密度低(如查塔姆群岛上以狩猎采集为生的人)、人数少(小环状珊瑚岛)、或人口密度低同时人数也少的一些岛屿上,经济仍然是最简单的。在这些社会中,每个家庭生产它所需要的东西;很少有或根本不存在经济的专业化。专业化在一些面积较大、人口密度较高的岛屿上发展起来,在萨摩亚、社会群岛、尤其是汤加和夏威夷达到了顶峰。汤加群岛和夏威夷群岛扶持兼职的世袭专门手艺人,包括独木舟建造者、航海者、石匠、捕鸟人和给人文身者。

Social complexity was similarly varied. Again, the Chathams and the atolls had the simplest, most egalitarian societies. While those islands retained the original Polynesian tradition of having chiefs, their chiefs wore little or no visible signs of distinction, lived in ordinary huts like those of commoners, and grew or caught their food like everyone else. Social distinctions and chiefly powers increased on high-density islands with large political units, being especially marked on Tonga and the Societies.

社会的复杂程度也同样存在着差异。查塔姆群岛和环状珊瑚岛仍然是最简单、最平等的社会。虽然这些岛屿保留了波利尼西亚人原来的设立首领的传统,但他们的首领的穿着很少有或根本看不出有什么特异之处,他们和平民一样住的是普通的茅屋,他们也和其他每一个人一样自己种粮食或捕捉食物来吃。在一些人口密度高、设有大行政单位的岛屿上,社会差别扩大了,首领的权力也增加了,这一现象在汤加和社会群岛尤为明显。

Social complexity again reached its peak in the Hawaiian Archipelago, where people of chiefly descent were divided into eight hierarchically ranked lineages. Members of those chiefly lineages did not intermarry with commoners but only with each other, sometimes even with siblings or half-siblings. Commoners had to prostrate themselves before high-ranking chiefs. All the members of chiefly lineages, bureaucrats, and some craft specialists were freed from the work of food production.

社会的复杂程度在夏威夷群岛达到了极点,那里有首领血统的人被分为8个等级森严的家族。这些家族的成员不与平民通婚,而只在家族内部通婚,有时甚至在同胞兄弟姊妹之间或同父异母或同母异父兄弟姊妹之间通婚。在高高在上的首领面前,平民必须倒地膜拜。首领家族的所有成员、官员和一些专门手艺人则被免除生产粮食的劳动。

Political organization followed the same trends. On the Chathams and atolls, the chiefs had few resources to command, decisions were reached by general discussion, and landownership rested with the community as a whole rather than with the chiefs. Larger, more densely populated political units concentrated more authority with the chiefs. Political complexity was greatest on Tonga and Hawaii, where the powers of hereditary chiefs approximated those of kings elsewhere in the world, and where land was controlled by the chiefs, not by the commoners. Using appointed bureaucrats as agents, chiefs requisitioned food from the commoners and also conscripted them to work on large construction projects, whose form varied from island to island: irrigation projects and fishponds on Hawaii, dance and feast centers on the Marquesas, chiefs' tombs on Tonga, and temples on Hawaii, the Societies, and Easter.

政治组织也遵循同样的趋势。在查塔姆群岛和环状珊瑚岛,首领可以掌握的资源不多,决定也是通过全体讨论作出的,土地所有权属于整个社区,而不属于首领。比较大的、人口比较密集的行政单位把更多的权力集中在首领手中。在汤加和夏威夷,政治的复杂程度最高,世袭首领的权力接近于世界上其他地方国王的权力,土地也由首领掌握,而不是由平民掌握。首领任命官员做代理人,利用他们向平民征用粮食,同时征召平民从事大型建筑工程的劳动,这些工程项目因岛而异:在夏威夷是灌溉工程和鱼塘,在马克萨斯群岛是舞蹈和宴会中心,在汤加是首领的陵墓,在夏威夷、社会群岛和复活节岛是庙宇。

At the time of Europeans' arrival in the 18th century, the Tongan chiefdom or state had already become an inter-archipelagal empire. Because the Tongan Archipelago itself was geographically close-knit and included several large islands with unfragmented terrain, each island became unified under a single chief; then the hereditary chiefs of the largest Tongan island (Tongatapu) united the whole archipelago, and eventually they conquered islands outside the archipelago up to 500 miles distant. They engaged in regular long-distance trade with Fiji and Samoa, established Tongan settlements in Fiji, and began to raid and conquer parts of Fiji. The conquest and administration of this maritime proto-empire were achieved by navies of large canoes, each holding up to 150 men.

当欧洲人于18世纪到达时,汤加的首领管辖区或国家业已成了一个由各群岛组成的帝国。由于汤加群岛本身在地理上紧密结合在一起,而且包含几个地形完整的大岛,所以每一个岛都在一个首领统治下统一起来;接着,汤加的最大岛屿(汤加塔布岛)的世袭首领们统一了整个群岛,并最后征服了该群岛以外的一些岛屿,最远的达500英里。他们与斐济和萨摩亚进行远距离定期贸易,在斐济建立汤加的殖民地,并开始劫掠和征服斐济的一些地区。对这个海洋原型帝国的征服和管理,都是靠每只最多可载150人的大独木舟组成的海军来实现的。

Like Tonga, Hawaii became a political entity encompassing several populous islands, but one confined to a single archipelago because of its extreme isolation. At the time of Hawaii's “discovery” by Europeans in 1778, political unification had already taken place within each Hawaiian island, and some political fusion between islands had begun. The four largest islands—Big Island (Hawaii in the narrow sense), Maui, Oahu, and Kauai—remained independent, controlling (or jockeying with each other for control of) the smaller islands (Lanai, Molokai, Kahoolawe, and Niihau). After the arrival of Europeans, the Big Island's King Kamehameha I rapidly proceeded with the consolidation of the largest islands by purchasing European guns and ships to invade and conquer first Maui and then Oahu. Kamehameha thereupon prepared invasions of the last independent Hawaiian island, Kauai, whose chief finally reached a negotiated settlement with him, completing the archipelago's unification.

同汤加一样,夏威夷也是一个行政实体,它包含几个人口众多的岛屿,但由于它的极其孤立的地理位置,它只是一个局限在一个群岛中的行政实体。当欧洲人于1778年“发现”夏威夷时,行政统一已在夏威夷的每一个岛的内部产生,而岛与岛之间的某种行政联合也已开始。最大的4个岛——大岛(狭义的夏威夷)、毛伊岛、瓦胡岛和考爱岛——仍然是独立的,它们控制着(或互相耍弄手腕图谋控制)较小的岛屿(拉奈岛、莫洛凯岛、卡胡拉韦岛和尼豪岛)。在欧洲人到达后,大岛国王卡米哈米哈一世购买欧洲的枪支和船只,迅速着手那几个最大岛屿的合并工作,以便首先入侵和征服毛伊岛,然后是瓦胡岛。卡米哈米哈随即又准备入侵夏威夷最后一个独立的岛屿——考爱岛,考爱岛的首领最后通过谈判与他达成了协议,从而完成了这个群岛的统一。

The remaining type of variation among Polynesian societies to be considered involves tools and other aspects of material culture. The differing availability of raw materials imposed an obvious constraint on material culture. At the one extreme was Henderson Island, an old coral reef raised above sea level and devoid of stone other than limestone. Its inhabitants were reduced to fabricating adzes out of giant clamshells. At the opposite extreme, the Maori on the minicontinent of New Zealand had access to a wide range of raw materials and became especially noted for their use of jade. Between those two extremes fell Polynesia's oceanic volcanic islands, which lacked granite, flint, and other continental rocks but did at least have volcanic rocks, which Polynesians worked into ground or polished stone adzes used to clear land for farming.

波利尼西亚各社会之间的其余一些需要予以考虑的差异,涉及工具与物质文化的其他方面。能否获得新材料的各种不同情况,对物质文化产生了明显的限制。一个极端是亨德森岛。这是一个高出海面的古老的珊瑚礁,除了石灰岩没有别的石头。它的居民竟然沦落到用巨大的蛤壳来做扁斧。在另一个极端,新西兰这个微型大陆上的毛利人则可以得到一系列原料,因而在利用玉石方面特别出名。处于这两个极端之间的是波利尼西亚的一些海洋火山岛,这些岛上虽然没有花岗岩、燧石和其他一些大陆岩石,但它们至少有火山岩,波利尼西亚人可以把它做成用来开荒种地的磨光石斧。

As for the types of artifacts made, the Chatham Islanders required little more than hand-held clubs and sticks to kill seals, birds, and lobsters. Most other islanders produced a diverse array of fishhooks, adzes, jewelry, and other objects. On the atolls, as on the Chathams, those artifacts were small, relatively simple, and individually produced and owned, while architecture consisted of nothing more than simple huts. Large and densely populated islands supported craft specialists who produced a wide range of prestige goods for chiefs—such as the feather capes reserved for Hawaiian chiefs and made of tens of thousands of bird feathers.

至于人工制品的种类,查塔姆群岛的岛民们除了用来杀死海豹、鸟和龙虾的手持棍棒外,几乎再不需要其他东西。其他大多数岛民则制造了大量的形形色色的鱼钩、扁斧、首饰和其他物品。在环状珊瑚岛上,例如在查塔姆群岛上,这些人工制品都很小,也比较简单,为个人所制造,也为个人所拥有,而建筑物也只是一些简单的茅屋。一些面积大而又人口密度高的岛屿则供养着一些专门手艺人,他们为首领制作了一系列令人羡慕的物品——例如羽毛斗篷,那是专门为首领们做的,需要用成千上万根鸟羽。

The largest products of Polynesia were the immense stone structures of a few islands—the famous giant statues of Easter Island, the tombs of Tongan chiefs, the ceremonial platforms of the Marquesas, and the temples of Hawaii and the Societies. This monumental Polynesian architecture was obviously evolving in the same direction as the pyramids of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Mexico, and Peru. Naturally, Polynesia's structures are not on the scale of those pyramids, but that merely reflects the fact that Egyptian pharaohs could draw conscript labor from a much larger human population than could the chief of any Polynesian island. Even so, the Easter Islanders managed to erect 30-ton stone statues—no mean feat for an island with only 7,000 people, who had no power source other than their own muscles.

波利尼西亚的最大产品要算几个岛上的巨型石头建筑——复活节岛上著名的雕像、汤加首领的陵墓、马克萨斯群岛上的举行仪式的平台以及夏威夷和社会群岛上的庙宇。波利尼西亚的这种纪念性建筑的演进方向,显然与埃及、美索不达米亚、墨西哥和秘鲁这些地方的金字塔相同。当然,波利尼西亚的这些建筑在规模上不及那些金字塔,但那只是反映了这样一个事实,即埃及的法老能够从多得多的人口中征调劳动力,而这是波利尼西亚的任何一个岛屿上的首领所无法做到的。即便如此,复活节岛的岛民们仍设法竖立起一些30吨重的雕像——对于一个只有7000人的岛屿来说,这可是一件了不起的事,因为这些人除了自己的一身肌肉外,没有任何其他动力来源。

THUS, POLYNESIAN ISLAND societies differed greatly in their economic specialization, social complexity, political organization, and material products, related to differences in population size and density, related in turn to differences in island area, fragmentation, and isolation and in opportunities for subsistence and for intensifying food production. All those differences among Polynesian societies developed, within a relatively short time and modest fraction of the Earth's surface, as environmentally related variations on a single ancestral society. Those categories of cultural differences within Polynesia are essentially the same categories that emerged everywhere else in the world.

因此,波利尼西亚的岛屿社会在其经济专业化、社会复杂程度、政治组织以及物质产品方面存在着巨大的差异。这些差异与人口的数量和密度的差异有关,又与岛屿的面积、地形破碎程度和隔离程度有关,也与维持生存和加强粮食生产的机会有关。波利尼西亚各社会之间的所有这些差异,都是在比较短的时间内和世界上一个不太大的地方逐步形成的,这些都是具有同一个祖先的社会里所发生的与环境有关的差异。波利尼西亚内部的这种种文化差异,基本上也就是世界上其他每一个地方所出现的那些差异。

Of course, the range of variation over the rest of the globe is much greater than that within Polynesia. While modern continental peoples included ones dependent on stone tools, as were Polynesians, South America also spawned societies expert in using precious metals, and Eurasians and Africans went on to utilize iron. Those developments were precluded in Polynesia, because no Polynesian island except New Zealand had significant metal deposits. Eurasia had full-fledged empires before Polynesia was even settled, and South America and Mesoamerica developed empires later, whereas Polynesia produced just two proto-empires, one of which (Hawaii) coalesced only after the arrival of Europeans. Eurasia and Mesoamerica developed indigenous writing, which failed to emerge in Polynesia, except perhaps on Easter Island, whose mysterious script may however have postdated the islanders' contact with Europeans.

当然,在世界其余地区的差异程度,要远远超过波利尼西亚群岛内的差异程度。虽然现代大陆民族也包括像波利尼西亚人那样的依靠石器的族群,但南美洲也产生了一些熟练使用贵金属的社会,而欧亚大陆的人和非洲人又进而利用铁器。这些发展阶段都不可能在波利尼西亚得到实现,因为除新西兰外,波利尼西亚没有一个岛有重要的金属矿床。甚至在波利尼西亚有人定居前,欧亚大陆已有了一些成熟的帝国,南美洲和中美洲在晚些时候也出现了帝国,而波利尼西亚这时才刚刚有了两个原型帝国,其中的一个(夏威夷)只是在欧洲人到达后才和另一个联合起来。欧亚大陆和中美洲有了本地的文字,而文字却没有在波利尼西亚出现,也许复活节岛是个例外,然而无论如何,那里的神秘文字可能出现在岛民与欧洲人发生接触之后。

That is, Polynesia offers us a small slice, not the full spectrum, of the world's human social diversity. That shouldn't surprise us, since Polynesia provides only a small slice of the world's geographic diversity. In addition, since Polynesia was colonized so late in human history, even the oldest Polynesian societies had only 3,200 years in which to develop, as opposed to at least 13,000 years for societies on even the last-colonized continents (the Americas). Given a few more millennia, perhaps Tonga and Hawaii would have reached the level of full-fledged empires battling each other for control of the Pacific, with indigenously developed writing to administer those empires, while New Zealand's Maori might have added copper and iron tools to their repertoire of jade and other materials.

这就是说,关于全世界人类社会的差异性问题,波利尼西亚给我们看到的只是一个小小的剖面,而不是全貌。这并不使我们感到意外,因为波利尼西亚给我们看到的只是全世界地理差异性的一个小小的剖面而已。此外,由于在人类历史上波利尼西亚的拓殖时间很晚,即使是历史最悠久的波利尼西亚社会,其发展时间也只有3200年,而即使是最后拓殖的大陆(美洲),其社会至少也有13000年的历史。如果再给汤加和夏威夷几千年时间,它们也会达到成熟帝国的水平,彼此为争夺对太平洋的控制权而战斗,用本土发展起来的文字来管理它们的帝国,而新西兰的毛利人也许会在他们用玉石和其他材料制作的全套作品外再加上铜器和铁器。

In short, Polynesia furnishes us with a convincing example of environmentally related diversification of human societies in operation. But we thereby learn only that it can happen, because it happened in Polynesia. Did it also happen on the continents? If so, what were the environmental differences responsible for diversification on the continents, and what were their consequences?

总之,关于现存人类社会的与环境有关的差异性问题,波利尼西亚为我们提供了一个令人信服的例证。但我们只能因此而知道这种情况可能会发生,因为它在波利尼西亚就曾发生过。这在所有大陆上是不是也发生过呢?如果发生过,那么造成这些大陆的差异性的环境差异是什么?这些差异所产生的结果又是什么?

注释:

1. 冈瓦纳大陆:被认为曾在南半球存在过的大陆,在中生代或古生代后期分裂成阿拉伯半岛、非洲、南美洲、南极洲、澳洲和印度半岛等。——译者