EPILOGUE

后记

THE FUTURE OF HUMAN HISTORY AS A SCIENCE

人类史作为一门科学的未来

YALI'S QUESTION WENT TO THE HEART OF THE CURRENT human condition, and of post-Pleistocene human history. Now that we have completed this brief tour over the continents, how shall we answer Yali?

耶利的问题触及了人类现状的实质,也是更新世后人类历史的关键所在。既然我们已经完成了这次对各大陆的短暂的巡视,我们将怎样来回答耶利呢?

I would say to Yali: the striking differences between the long-term histories of peoples of the different continents have been due not to innate differences in the peoples themselves but to differences in their environments. I expect that if the populations of Aboriginal Australia and Eurasia could have been interchanged during the Late Pleistocene, the original Aboriginal Australians would now be the ones occupying most of the Americas and Australia, as well as Eurasia, while the original Aboriginal Eurasians would be the ones now reduced to downtrodden population fragments in Australia. One might at first be inclined to dismiss this assertion as meaningless, because the experiment is imaginary and my claim about its outcome cannot be verified. But historians are nevertheless able to evaluate related hypotheses by retrospective tests. For instance, one can examine what did happen when European farmers were transplanted to Greenland or the U.S. Great Plains, and when farmers stemming ultimately from China emigrated to the Chatham Islands, the rain forests of Borneo, or the volcanic soils of Java or Hawaii. These tests confirm that the same ancestral peoples either ended up extinct, or returned to living as hunter-gatherers, or went on to build complex states, depending on their environments. Similarly, Aboriginal Australian hunter-gatherers, variously transplanted to Flinders Island, Tasmania, or southeastern Australia, ended up extinct, or as hunter-gatherers with the modern world's simplest technology, or as canal builders intensively managing a productive fishery, depending on their environments.

我会对耶利这样说:各大陆民族长期历史之间的显著差异,不是由于这些民族本身的天生差异,而是由于他们环境的差异。我猜想,如果在更新世晚期能够使澳大利亚土著人口和欧亚大陆土著人口互换位置,那么,原来的澳大利亚土著现在可能不但占领了欧亚大陆,而且也占领了美洲和澳大利亚的大部分地区,而原来的欧亚大陆土著现在可能已沦为澳大利亚的一些遭受蹂躏的零星分散的人口。对于这种说法,你一开始可能会认为毫无意义而不屑一顾,因为这个实验是想象出来的,而我所说的那种结果也是不可能证明的。但历史学家却能用回溯试验法对有关的假说进行评价。例如,我们可以考察一下,如果把欧洲农民迁到格陵兰或美国的大平原,如果本来出身于中国的农民移居查塔姆群岛、婆罗洲的雨林、爪哇或夏威夷的火山土地带,会发生什么情况。这些试验证明,这些具有共同祖先的民族或者最后灭绝了,或者重新回到狩猎采集的生活,或者进而建立视环境而定的复杂国家。同样,如果把澳大利亚土著狩猎采集族群迁到弗林德斯岛、塔斯马尼亚岛或澳大利亚南部,他们或者最后归于灭绝,或者成为掌握现代世界最简单技术的狩猎采集族群,或者成为根据环境修建沟渠、集约经营高产渔场的人。

Of course, the continents differ in innumerable environmental features affecting trajectories of human societies. But a mere laundry list of every possible difference does not constitute an answer to Yali's question. Just four sets of differences appear to me to be the most important ones.

当然,各大陆的环境有无数的不同特点,正是这些不同的特点影响了人类社会的发展轨迹。不过,仅仅列出每一种可能的差异还不足以回答耶利的问题。在我看来,只有4组差异是最重要的。

The first set consists of continental differences in the wild plant and animal species available as starting materials for domestication. That's because food production was critical for the accumulation of food surpluses that could feed non-food-producing specialists, and for the buildup of large populations enjoying a military advantage through mere numbers even before they had developed any technological or political advantage. For both of those reasons, all developments of economically complex, socially stratified, politically centralized societies beyond the level of small nascent chiefdoms were based on food production.

第一组差异是各大陆在可以用作驯化的起始物种的野生动植物品种方面的差异。这是因为,粮食生产之所以具有决定性的意义,在于它能积累剩余粮食以养活不从事粮食生产的专门人材,同时也在于它能形成众多的人口,从而甚至在发展出任何技术和政治优势之前,仅仅凭借人多就可以拥有军事上的优势。由于这两个原因,从小小的不成熟的酋长管辖地阶段向经济上复杂的、社会上分层次的、政治上集中的社会发展的各个阶段,都是以粮食生产为基础的。

But most wild animal and plant species have proved unsuitable for domestication: food production has been based on relatively few species of livestock and crops. It turns out that the number of wild candidate species for domestication varied greatly among the continents, because of differences in continental areas and also (in the case of big mammals) in Late Pleistocene extinctions. These extinctions were much more severe in Australia and the Americas than in Eurasia or Africa. As a result, Africa ended up biologically somewhat less well endowed than the much larger Eurasia, the Americas still less so, and Australia even less so, as did Yali's New Guinea (with one-seventieth of Eurasia's area and with all of its original big mammals extinct in the Late Pleistocene).

但大多数野生的动植物品种证明是不适于驯化的:粮食生产的基础一直是比较少的几种牲畜和作物。原来,各大陆在可以用于驯化的野生动植物的数量方面差异很大,因为各大陆的面积不同,而且在更新世晚期大型哺乳动物灭绝的情况也不同。大型哺乳动物灭绝的情况,在澳大利亚和美洲要比在欧亚大陆或非洲严重得多。因此,就生物物种来说,欧亚大陆最为得天独厚,非洲次之,美洲又次之,而澳大利亚最下,就像耶利的新几内亚那种情况(新几内亚的面积为欧亚大陆的七十分之一,而且其原来的大型哺乳动物在更新世晚期即已灭绝)。

On each continent, animal and plant domestication was concentrated in a few especially favorable homelands accounting for only a small fraction of the continent's total area. In the case of technological innovations and political institutions as well, most societies acquire much more from other societies than they invent themselves. Thus, diffusion and migration within a continent contribute importantly to the development of its societies, which tend in the long run to share each other's developments (insofar as environments permit) because of the processes illustrated in such simple form by Maori New Zealand's Musket Wars. That is, societies initially lacking an advantage either acquire it from societies possessing it or (if they fail to do so) are replaced by those other societies.

在每一个大陆,动植物的驯化集中在只占该大陆总面积很小一部分的几个条件特别有利的中心地。就技术创新和政治体制来说,大多数社会从其他社会获得的要比它们自己发明的多得多。因此,一个大陆内部的传播与迁移,对它的社会的发展起着重要的促进作用,而从长远来看,由于毛利人的新西兰火枪战争以如此简单的形式所揭示的过程,这些社会又(在环境许可的情况下)分享彼此的发展成果。就是说,起初缺乏某种有利条件的社会或者从拥有这种条件的社会那里得到,或者(如果做不到这一点)被其他这些社会所取代。

Hence a second set of factors consists of those affecting rates of diffusion and migration, which differed greatly among continents. They were most rapid in Eurasia, because of its east-west major axis and its relatively modest ecological and geographical barriers. The reasoning is straightforward for movements of crops and livestock, which depend strongly on climate and hence on latitude. But similar reasoning also applies to the diffusion of technological innovations, insofar as they are best suited without modification to specific environments. Diffusion was slower in Africa and especially in the Americas, because of those continents' north-south major axes and geographic and ecological barriers. It was also difficult in traditional New Guinea, where rugged terrain and the long backbone of high mountains prevented any significant progress toward political and linguistic unification.

因此,第二组因素就是那些影响传播和迁移速度的因素,而这种速度在大陆与大陆之间差异很大。在欧亚大陆速度最快,这是由于它的东西向的主轴线和它的相对而言不太大的生态与地理障碍。对于作物和牲畜的传播来说,这个道理是最简单不过的,因为这种传播大大依赖于气候因而也就是大大依赖于纬度。同样的道理也适用于技术的发明,如果不用对特定环境加以改变就能使这些发明得到最充分的利用的话。传播的速度在非洲就比较缓慢了,而在美洲就尤其缓慢,这是由于这两个大陆的南北向的主轴线和地理与生态障碍。在传统的新几内亚,这种传播也很困难,因为那里崎岖的地形和高山漫长的主脉妨碍了政治和语言统一的任何重大进展。

Related to these factors affecting diffusion within continents is a third set of factors influencing diffusion between continents, which may also help build up a local pool of domesticates and technology. Ease of intercontinental diffusion has varied, because some continents are more isolated than others. Within the last 6,000 years it has been easiest from Eurasia to sub-Saharan Africa, supplying most of Africa's species of livestock. But interhemispheric diffusion made no contribution to Native America's complex societies, isolated from Eurasia at low latitudes by broad oceans, and at high latitudes by geography and by a climate suitable just for hunting-gathering. To Aboriginal Australia, isolated from Eurasia by the water barriers of the Indonesian Archipelago, Eurasia's sole proven contribution was the dingo.

与影响大陆内部传播的这些因素有关的,是第三组影响大陆之间传播的因素,这些因素也可能有助于积累一批本地的驯化动植物和技术。大陆与大陆之间传播的难易程度是不同的,因为某些大陆比另一些大陆更为孤立。在过去的6000年中,传播最容易的是从欧亚大陆到非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区,非洲大部分牲畜就是通过这种传播得到的。但东西两半球之间的传播,则没有对美洲的复杂社会作出过任何贡献,这些社会在低纬度与欧亚大陆隔着宽阔的海洋,而在高纬度又在地形和适合狩猎采集生活的气候方面与欧亚大陆相去甚远。对于原始的澳大利亚来说,由于印度尼西亚群岛的一道道水上障碍把它同欧亚大陆隔开,欧亚大陆对它的唯一的得到证明的贡献就是澳洲野狗。

The fourth and last set of factors consists of continental differences in area or total population size. A larger area or population means more potential inventors, more competing societies, more innovations available to adopt—and more pressure to adopt and retain innovations, because societies failing to do so will tend to be eliminated by competing societies. That fate befell African pygmies and many other hunter-gatherer populations displaced by farmers. Conversely, it also befell the stubborn, conservative Greenland Norse farmers, replaced by Eskimo hunter-gatherers whose subsistence methods and technology were far superior to those of the Norse under Greenland conditions. Among the world's landmasses, area and the number of competing societies were largest for Eurasia, much smaller for Australia and New Guinea and especially for Tasmania. The Americas, despite their large aggregate area, were fragmented by geography and ecology and functioned effectively as several poorly connected smaller continents.

第四组也是最后一组因素是各大陆之间在面积和人口总数方面的差异。更大的面积或更多的人口意味着更多的潜在的发明者,更多的互相竞争的社会,更多的可以采用的发明创造——以及更大的采用和保有发明创造的压力,因为任何社会如果不这样做就往往会被竞争的对手所淘汰。非洲的俾格米人和其他许多被农民取代的狩猎采集群体,就曾碰到这样的命运。相反的例子是格陵兰岛上顽固保守的古挪威农民,他们也碰到了被爱斯基摩狩猎采集族群所取代的命运,因为在格陵兰的条件下,这些爱斯基摩人的生存方法和生存技术都比这些古挪威人优越得多。在全世界的陆块中,欧亚大陆的面积最大,相互竞争的社会的数量也最多,澳大利亚和新几内亚在这方面就差得多,而塔斯马尼亚更是瞠乎其后。美洲的总面积虽然很大,但却在地理上和生态上支离破碎,实际上就像几个没有紧密联系的较小的大陆。

Those four sets of factors constitute big environmental differences that can be quantified objectively and that are not subject to dispute. While one can contest my subjective impression that New Guineans are on the average smarter than Eurasians, one cannot deny that New Guinea has a much smaller area and far fewer big animal species than Eurasia. But mention of these environmental differences invites among historians the label “geographic determinism,” which raises hackles. The label seems to have unpleasant connotations, such as that human creativity counts for nothing, or that we humans are passive robots helplessly programmed by climate, fauna, and flora. Of course these fears are misplaced. Without human inventiveness, all of us today would still be cutting our meat with stone tools and eating it raw, like our ancestors of a million years ago. All human societies contain inventive people. It's just that some environments provide more starting materials, and more favorable conditions for utilizing inventions, than do other environments.

这4组因素构成了环境的巨大差异,这些差异可以客观地用数量来表示,而且不会引起争议。我的主观印象是新几内亚人一般要比欧亚大陆人聪明,尽管人们可以对此提出质疑,但他们无法否认新几内亚的面积比欧亚大陆小得多,新几内亚的大型动物品种也比欧亚大陆少得多。但是,提起这些环境差异不免会使历史学家们贴上那使人火冒三丈的“地理决定论”的标签。这种标签似乎具有令人不愉快的含义,因为这等于是说人类的创造性毫无价值,或者说我们人类只是无可奈何地被气候、动物区系和植物区系编上了程序的被动的机器人。当然,这种疑虑是没有根据的。如果没有人类的创造性,我们今天可能全都仍然在用石器切肉,茹毛饮血,就像100万年前我们的祖先所做的那样。所有的人类社会都拥有有发明才能的人。事情恰恰是有些环境比另一些环境提供了更多的起始物种和利用发明的更有利的条件。

THESE ANSWERS TO Yali's question are longer and more complicated than Yali himself would have wanted. Historians, however, may find them too brief and oversimplified. Compressing 13,000 years of history on all continents into a 400-page book works out to an average of about one page per continent per 150 years, making brevity and simplification inevitable. Yet the compression brings a compensating benefit: long-term comparisons of regions yield insights that cannot be won from short-term studies of single societies.

这些答案比起耶利本人可能想要得到的答案来显得冗长和复杂。然而,历史学家们则可能认为这些答案太短、太简单了。把各个大陆的13000年的历史压缩成一本400多页的书,等于大约每150年每个大陆平均分摊到一页,这样,精练、简化就在所难免。不过,这种压缩也带来了一个补偿性的好处:对一些地区从长期范围内进行比较所产生的真知灼见,是对单一社会所进行的短期范围内的研究不可能得到的。

Naturally, a host of issues raised by Yali's question remain unresolved. At present, we can put forward some partial answers plus a research agenda for the future, rather than a fully developed theory. The challenge now is to develop human history as a science, on a par with acknowledged historical sciences such as astronomy, geology, and evolutionary biology. Hence it seems appropriate to conclude this book by looking to the future of the discipline of history, and by outlining some of the unresolved issues.

当然,耶利的问题所提出的一系列争议仍然没有解决。目前,我们只能提出一些不完全的答案和未来的研究事项,而不是一种充分展开的理论。现在需要努力去做的事,就是把人类史发展成为一门科学,使之与天文学、地质学和演化生物学这些公认的历史科学并驾齐驱。因此,展望一下历史这门学科的未来,并概括地提出一些尚未解决的问题从而结束本书,似乎是恰当之举。

The most straightforward extension of this book will be to quantify further, and thus to establish more convincingly the role of, intercontinental differences in the four sets of factors that appear to be most important. To illustrate differences in starting materials for domestication, I provided numbers for each continent's total of large wild terrestrial mammalian herbivores and omnivores (Table 9.2) and of large-seeded cereals (Table 8.1). One extension would be to assemble corresponding numbers for large-seeded legumes (pulses), such as beans, peas, and vetches. In addition, I mentioned factors disqualifying big mammalian candidates for domestication, but I did not tabulate how many candidates are disqualified by each factor on each continent. It would be interesting to do so, especially for Africa, where a higher percentage of candidates is disqualified than in Eurasia: which disqualifying factors are most important in Africa, and what has selected for their high frequency in African mammals? Quantitative data should also be assembled to test my preliminary calculations suggesting differing rates of diffusion along the major axes of Eurasia, the Americas, and Africa.

我们已经提出了4组似乎最重要的因素,以说明各大陆之间的种种差异。因此,本书的最直接的延伸应是进一步地用数量来表示这些差异,从而更令人信服地证实这些差异的作用。为了说明用于驯化的起始物种方面的差异,我曾提供了一些数字,说明每个大陆总共有多少大型野生陆栖哺乳类食草动物(表9.2)和有多少大籽粒谷物(表8.1)。本书的一个延伸部分可能是把诸如菜豆、豌豆和野豌豆之类大籽粒豆科植物(豆类植物)的相应数目收集起来。此外,我提到过一些使大型哺乳动物失去驯化候补资格的因素,但我没有用表格列出每个大陆有多少这样的候补动物由于每一个这样的因素而失去驯化资格。这样做是一件很有意思的事,尤其对非洲来说是这样,因为在非洲失去驯化资格的候补动物的百分比比在欧亚大陆高:在使一些动物失去驯化的候补资格的各种因素中,哪些因素在非洲最为重要,以及是什么选择决定了非洲哺乳动物十分频繁地失去驯化的候补资格?还应收集一些能用数量说明的资料,来验证我对表明沿欧亚大陆、美洲和非洲主要轴线的不同传播速度所作的初步计算。

A SECOND EXTENSION will be to smaller geographic scales and shorter time scales than those of this book. For instance, the following obvious question has probably occurred to readers already: why, within Eurasia, were European societies, rather than those of the Fertile Crescent or China or India, the ones that colonized America and Australia, took the lead in technology, and became politically and economically dominant in the modern world? A historian who had lived at any time between 8500 B.C. and A.D. 1450, and who had tried then to predict future historical trajectories, would surely have labeled Europe's eventual dominance as the least likely outcome, because Europe was the most backward of those three Old World regions for most of those 10,000 years. From 8500 B.C. until the rise of Greece and then Italy after 500 B.C., almost all major innovations in western Eurasia—animal domestication, plant domestication, writing, metallurgy, wheels, states, and so on—arose in or near the Fertile Crescent. Until the proliferation of water mills after about A.D. 900, Europe west or north of the Alps contributed nothing of significance to Old World technology or civilization; it was instead a recipient of developments from the eastern Mediterranean, Fertile Crescent, and China. Even from A.D. 1000 to 1450 the flow of science and technology was predominantly into Europe from the Islamic societies stretching from India to North Africa, rather than vice versa. During those same centuries China led the world in technology, having launched itself on food production nearly as early as the Fertile Crescent did.

本书的第二个延伸部分将涉及比本书已经论述的更小的地理范围和更短的时间范围。例如,下面的一个显而易见的问题可能已被读者们想到了:在欧亚大陆范围内,为什么是欧洲社会,即在美洲和澳大利亚殖民的那些社会,而不是新月沃地的社会或中国和印度的社会,在技术上领先,并在现代世界上占据政治和经济的支配地位?如果一个历史学家生活在从公元前8500年到公元1450年的任何一段时间内,如果他当时试图预测未来的历史发展轨迹,他肯定会认为,欧洲最终的支配地位是最不可能发生的结果,因为欧洲在过去那1万年的大部分时间里是旧大陆的那3个地区中最落后的一个地区。从公元前8500年直到公元500年后,先是希腊后是意大利兴起的,这一段时间里,欧亚大陆西部几乎所有的重大发明——动物驯化、植物驯化、文学、冶金术、轮子、国家等等——都是在新月沃地或其附近出现的。在水磨于大约公元900年后大量传播之前,阿尔卑斯山以西或以北的欧洲没有对旧大陆的技术或文明作出过任何有意义的贡献,它只是一个从地中海以东、新月沃地和中国接受发展成果的地方。甚至从公元1000年到1450年,科学和技术绝大多数都是从印度与北非之间的伊斯兰社会传入欧洲,而不是相反。就在那几个世纪中,中国在技术上走在世界的前列,几乎和新月沃地一样早地开始了粮食生产。

Why, then, did the Fertile Crescent and China eventually lose their enormous leads of thousands of years to late-starting Europe? One can, of course, point to proximate factors behind Europe's rise: its development of a merchant class, capitalism, and patent protection for inventions, its failure to develop absolute despots and crushing taxation, and its Greco-Judeo-Christian tradition of critical empirical inquiry. Still, for all such proximate causes one must raise the question of ultimate cause: why did these proximate factors themselves arise in Europe, rather than in China or the Fertile Crescent?

那么,为什么新月沃地和中国把它们几千年的巨大的领先优势最后让给了起步晚的欧洲?当然,人们可以指出促使欧洲兴起的一些直接因素:它的商人阶级、资本主义和对发明的专利保护的逐步形成,它的未能产生专制独裁的君主和使人不堪重负的税收,以及它的希腊-犹太教-基督教的批判经验主义调查研究的传统。不过,对于所有这些直接原因,人们一定会提出关于终极原因的问题:为什么这些直接因素出现在欧洲,而不是出现在中国或新月沃地?

For the Fertile Crescent, the answer is clear. Once it had lost the head start that it had enjoyed thanks to its locally available concentration of domesticable wild plants and animals, the Fertile Crescent possessed no further compelling geographic advantages. The disappearance of that head start can be traced in detail, as the westward shift in powerful empires. After the rise of Fertile Crescent states in the fourth millennium B.C., the center of power initially remained in the Fertile Crescent, rotating between empires such as those of Babylon, the Hittites, Assyria, and Persia. With the Greek conquest of all advanced societies from Greece east to India under Alexander the Great in the late fourth century B.C., power finally made its first shift irrevocably westward. It shifted farther west with Rome's conquest of Greece in the second century B.C., and after the fall of the Roman Empire it eventually moved again, to western and northern Europe.

就新月沃地而言,答案是清楚的。新月沃地由于当地集中了可以驯化的动植物而拥有了领先优势。如果它一旦失去了这种优势,它就不再有任何引人注目的地理优势可言。这种领先优势在一些强大帝国西移的过程中消失了,这种情况可以详细地描绘出来。在公元前第四个1千年中新月沃地的一些国家兴起后,权力中心起初仍然在新月沃地,轮流为巴比伦、赫梯、亚述和波斯这些帝国。随着希腊人在亚历山大大帝领导下于公元前4世纪末征服从希腊向东直到印度的所有先进的社会,权力终于第一次无可挽回地西移。随着罗马在公元前2世纪征服希腊,权力又进一步西移,而在罗马帝国灭亡后,权力最后又向欧洲西部和北部转移。

The major factor behind these shifts becomes obvious as soon as one compares the modern Fertile Crescent with ancient descriptions of it. Today, the expressions “Fertile Crescent” and “world leader in food production” are absurd. Large areas of the former Fertile Crescent are now desert, semidesert, steppe, or heavily eroded or salinized terrain unsuited for agriculture. Today's ephemeral wealth of some of the region's nations, based on the single nonrenewable resource of oil, conceals the region's long-standing fundamental poverty and difficulty in feeding itself.

只要把现代的新月沃地和古人对它的描写加以比较,促使权力西移的主要因素就立刻变得显而易见。今天,“新月沃地”和“粮食生产世界领先”这些说法是荒唐可笑的。过去的新月沃地的广大地区现在成了沙漠、半沙漠、干草原和不适合农业的受到严重侵蚀或盐碱化的土地。这个地区的某些国家的短暂财富是建立在单一的不能再生的石油资源的基础上的,这一现象掩盖了这个地区的长期贫困和难以养活自己的情况。

In ancient times, however, much of the Fertile Crescent and eastern Mediterranean region, including Greece, was covered with forest. The region's transformation from fertile woodland to eroded scrub or desert has been elucidated by paleobotanists and archaeologists. Its woodlands were cleared for agriculture, or cut to obtain construction timber, or burned as firewood or for manufacturing plaster. Because of low rainfall and hence low primary productivity (proportional to rainfall), regrowth of vegetation could not keep pace with its destruction, especially in the presence of overgrazing by abundant goats. With the tree and grass cover removed, erosion proceeded and valleys silted up, while irrigation agriculture in the low-rainfall environment led to salt accumulation. These processes, which began in the Neolithic era, continued into modern times. For instance, the last forests near the ancient Nabataean capital of Petra, in modern Jordan, were felled by the Ottoman Turks during construction of the Hejaz railroad just before World War I.

然而,在古代,在新月沃地和包括希腊在内的东地中海地区,很多地方都覆盖着森林。这个地区从肥沃的林地变成受到侵蚀的低矮丛林地或沙漠的过程,已经得到古植物学家和考古学家的说明。它的林地或者被开垦以发展农业,或者被砍伐以获得建筑用的木材,或者被当作木柴烧掉,或者被用来烧制石膏。由于雨量少因而初级生产力(与雨量成正比)也低,这样,植被的再生赶不上破坏的速度,尤其在存在大量山羊过度放牧的情况下是这样。由于没有了树木和草皮,土壤侵蚀发生了,溪谷淤塞了,而在雨量少的环境里的灌溉农业导致了土壤中盐分的积累。这些过程在新石器时代就已开始了,一直继续到现代。例如,现今约旦的古代纳巴泰国首都皮特拉附近的最后一批森林,是在第一次世界大战前被奥斯曼土耳其人修建希贾兹 [1]铁路时砍光的。

Thus, Fertile Crescent and eastern Mediterranean societies had the misfortune to arise in an ecologically fragile environment. They committed ecological suicide by destroying their own resource base. Power shifted westward as each eastern Mediterranean society in turn undermined itself, beginning with the oldest societies, those in the east (the Fertile Crescent). Northern and western Europe has been spared this fate, not because its inhabitants have been wiser but because they have had the good luck to live in a more robust environment with higher rainfall, in which vegetation regrows quickly. Much of northern and western Europe is still able to support productive intensive agriculture today, 7,000 years after the arrival of food production. In effect, Europe received its crops, livestock, technology, and writing systems from the Fertile Crescent, which then gradually eliminated itself as a major center of power and innovation.

因此,新月沃地和东地中海社会不幸在一个生态脆弱的环境中兴起。它们破坏了自己的资源基础,无异于生态自杀。从东方(新月沃地)最古老的社会开始,每一个东地中海社会都在轮流地自挖墙脚,而就在这个过程中,权力西移了。欧洲北部和西部没有遭到同样的命运,这不是因为那里的居民比较明智,而是因为他们运气好,碰巧生活在一个雨量充沛、植被再生迅速的好环境里。在粮食生产传入7000年之后,欧洲北部和西部的广大地区今天仍能维持高产的集约农业。事实上,欧洲是从新月沃地得到它的作物、牲畜、技术和书写系统的,而新月沃地后来反而使自己失去了作为一个主要的权力和发明中心的地位。

That is how the Fertile Crescent lost its huge early lead over Europe. Why did China also lose its lead? Its falling behind is initially surprising, because China enjoyed undoubted advantages: a rise of food production nearly as early as in the Fertile Crescent; ecological diversity from North to South China and from the coast to the high mountains of the Tibetan plateau, giving rise to a diverse set of crops, animals, and technology; a large and productive expanse, nourishing the largest regional human population in the world; and an environment less dry or ecologically fragile than the Fertile Crescent's, allowing China still to support productive intensive agriculture after nearly 10,000 years, though its environmental problems are increasing today and are more serious than western Europe's.

这就是新月沃地失去它对欧洲的巨大的早期领先优势的情形。为什么中国也失去了这种领先优势呢?中国的落后起初是令人惊讶的,因为中国拥有无可置疑的有利条件:粮食生产的出现似乎同在新月沃地一样早;从华北到华南,从沿海地区到西藏高原的高山地区的生态多样性,产生了一批不同的作物、动物和技术;幅员广阔,物产丰富,养活了这一地区世界上最多的人口;以及一个不像新月沃地那样干旱或生态脆弱的环境,使中国在将近1万年之后仍能维持高产的集约农业,虽然它的环境问题日益增多,而且比欧洲西部严重。

These advantages and head start enabled medieval China to lead the world in technology. The long list of its major technological firsts includes cast iron, the compass, gunpowder, paper, printing, and many others mentioned earlier. It also led the world in political power, navigation, and control of the seas. In the early 15th century it sent treasure fleets, each consisting of hundreds of ships up to 400 feet long and with total crews of up to 28,000, across the Indian Ocean as far as the east coast of Africa, decades before Columbus's three puny ships crossed the narrow Atlantic Ocean to the Americas' east coast. Why didn't Chinese ships proceed around Africa's southern cape westward and colonize Europe, before Vasco da Gama's own three puny ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope eastward and launched Europe's colonization of East Asia? Why didn't Chinese ships cross the Pacific to colonize the Americas' west coast? Why, in brief, did China lose its technological lead to the formerly so backward Europe?

这些有利条件和领先优势使得中世纪的中国在技术上领先世界。中国一长串重大的技术第一包括铸铁、罗盘、火药、纸、印刷术以及前面提到过的其他许多发明。它在政治权力、航海和海上管制方面也曾在世界上领先。15世纪初,它派遣宝船队 [2]横渡印度洋,远达非洲东海岸,每支船队由几百艘长达400英尺的船只和总共2800人组成。这些航行在时间上也比哥伦布率领3艘不起眼的小船渡过狭窄的大西洋到达美洲东海岸要早好几十年。法斯科·达·伽马率领他的3艘不起眼的小船,绕过非洲的好望角向东航行,使欧洲开始了对东亚的殖民。为什么中国的船只没有在伽马之前绕过好望角向西航行并在欧洲殖民?为什么中国的船只没有横渡太平洋到美洲西海岸来殖民?简而言之,为什么中国把自己在技术上的领先优势让给原先十分落后的欧洲呢?

The end of China's treasure fleets gives us a clue. Seven of those fleets sailed from China between A.D. 1405 and 1433. They were then suspended as a result of a typical aberration of local politics that could happen anywhere in the world: a power struggle between two factions at the Chinese court (the eunuchs and their opponents). The former faction had been identified with sending and captaining the fleets. Hence when the latter faction gained the upper hand in a power struggle, it stopped sending fleets, eventually dismantled the shipyards, and forbade oceangoing shipping. The episode is reminiscent of the legislation that strangled development of public electric lighting in London in the 1880s, the isolationism of the United States between the First and Second World Wars, and any number of backward steps in any number of countries, all motivated by local political issues. But in China there was a difference, because the entire region was politically unified. One decision stopped fleets over the whole of China. That one temporary decision became irreversible, because no shipyards remained to turn out ships that would prove the folly of that temporary decision, and to serve as a focus for rebuilding other shipyards.

中国西洋舰队的结局给了我们一条线索。从公元1405年到1433年,这些船队一共有7次从中国扬帆远航。后来,由于世界上任何地方都可能发生的一种局部的政治变化,船队出海远航的事被中止了:中国朝廷上的两派(太监和反对他们的人)之间发生了权力斗争。前一派支持派遣和指挥船队远航。因此,当后一派在权力斗争中取得上风时,它停止派遣船队,最后还拆掉船坞并禁止远洋航运。这一事件使我们想起了19世纪80年代伦敦的扼杀公共电灯照明的立法、第一次和第二次世界大战之间美国的孤立主义和许多国家全都由于局部的政治争端而引发的许多倒退措施。但在中国,情况有所不同,因为那整个地区在政治上是统一的。一个决定就使整个中国停止了船队的航行。那个一时的决定竟是不可逆转的,因为已不再有任何船坞来造船以证明那个一时的决定的愚蠢,也不再有任何船坞可以用作重建新船坞的中心。

Now contrast those events in China with what happened when fleets of exploration began to sail from politically fragmented Europe. Christopher Columbus, an Italian by birth, switched his allegiance to the duke of Anjou in France, then to the king of Portugal. When the latter refused his request for ships in which to explore westward, Columbus turned to the duke of Medina-Sedonia, who also refused, then to the count of Medina-Celi, who did likewise, and finally to the king and queen of Spain, who denied Columbus's first request but eventually granted his renewed appeal. Had Europe been united under any one of the first three rulers, its colonization of the Americas might have been stillborn.

现在来对比一下中国的这些事件和一些探险船队开始从政治上分裂的欧洲远航时所发生的事情。克里斯托弗·哥伦布出生在意大利,后来转而为法国的昂儒公爵服务,又后来改事葡萄牙国王。哥伦布曾请求国王派船让他向西航行探险。他的请求被国王拒绝了,于是他就求助于梅迪纳-塞多尼亚公爵,也遭到了拒绝,接着他又求助于梅迪纳-塞利伯爵,依然遭到拒绝,最后他又求助于西班牙的国王和王后,他们拒绝了他的第一次请求,但后来在他再次提出请求时总算同意了。如果欧洲在这头3个统治者中任何一个的统治下统一起来,它对美洲的殖民也许一开始就失败了。

In fact, precisely because Europe was fragmented, Columbus succeeded on his fifth try in persuading one of Europe's hundreds of princes to sponsor him. Once Spain had thus launched the European colonization of America, other European states saw the wealth flowing into Spain, and six more joined in colonizing America. The story was the same with Europe's cannon, electric lighting, printing, small firearms, and innumerable other innovations: each was at first neglected or opposed in some parts of Europe for idiosyncratic reasons, but once adopted in one area, it eventually spread to the rest of Europe.

事实上,正是由于欧洲是分裂的,哥伦布才成功地第五次在几百个王公贵族中说服一个来赞助他的航海事业。一旦西班牙这样开始了欧洲对美洲的殖民,其他的欧洲国家看到财富滚滚流入西班牙,立刻又有6个欧洲国家加入了对美洲殖民的行列。对于欧洲的大炮、电灯照明、印刷术、小型火器和无数的其他发明,情况也是如此:每一项发明在欧洲的一些地方由于人们的习性起先或者被人忽视,或者遭人反对,但一旦某个地区采用了它,它最后总能传播到欧洲的其余地区。

These consequences of Europe's disunity stand in sharp contrast to those of China's unity. From time to time the Chinese court decided to halt other activities besides overseas navigation: it abandoned development of an elaborate water-driven spinning machine, stepped back from the verge of an industrial revolution in the 14th century, demolished or virtually abolished mechanical clocks after leading the world in clock construction, and retreated from mechanical devices and technology in general after the late 15th century. Those potentially harmful effects of unity have flared up again in modern China, notably during the madness of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, when a decision by one or a few leaders closed the whole country's school systems for five years.

欧洲分裂所产生的这些结果与中国统一所产生的结果形成了鲜明的对比。除了作出停止海外航行的决定外,中国的朝廷还作出停止其他一些活动的决定:放弃开发一种精巧的水力驱动的纺纱机,在14世纪从一场产业革命的边缘退了回来,在制造机械钟方面领先世界后又把它拆毁或几乎完全破坏了,以及在15世纪晚期以后不再发展机械装置和一般技术。统一的这些潜在的有害影响在现代中国又死灰复燃,特别是20世纪60年代和70年代“文化大革命”中的那种狂热,当时一个或几个领导人的决定就把全国的学校系统关闭了5年之久。

China's frequent unity and Europe's perpetual disunity both have a long history. The most productive areas of modern China were politically joined for the first time in 221 B.C. and have remained so for most of the time since then. China has had only a single writing system from the beginnings of literacy, a single dominant language for a long time, and substantial cultural unity for two thousand years. In contrast, Europe has never come remotely close to political unification: it was still splintered into 1,000 independent statelets in the 14th century, into 500 statelets in A.D. 1500, got down to a minimum of 25 states in the 1980s, and is now up again to nearly 40 at the moment that I write this sentence. Europe still has 45 languages, each with its own modified alphabet, and even greater cultural diversity. The disagreements that continue today to frustrate even modest attempts at European unification through the European Economic Community (EEC) are symptomatic of Europe's ingrained commitment to disunity.

中国的经常统一与欧洲的永久分裂都由来已久。现代中国的最肥沃地区于公元前221年第一次在政治上统一起来,并从那时以来的大部分时间里一直维持着这个局面。中国自有文字以来就一直只有一种书写系统,长期以来只有一种占支配地位的语言,以及2000年来牢固的文化统一。相比之下,欧洲与统一始终相隔十万八千里:14世纪时它仍然分裂成1000个独立的小国,公元1500年有小国500个,20世纪80年代减少到最低限度的25国,而现在就在我写这句话的时候又上升到将近40个国家。欧洲仍然有45种语言,每种语言都有自己的经过修改的字母表,而文化的差异甚至更大。欧洲内部的分歧今天在继续挫败甚至是想要通过欧洲经济共同体(EEC)来实现欧洲统一的并不过分的企图,这就表明欧洲对分裂的根深蒂固的执著。

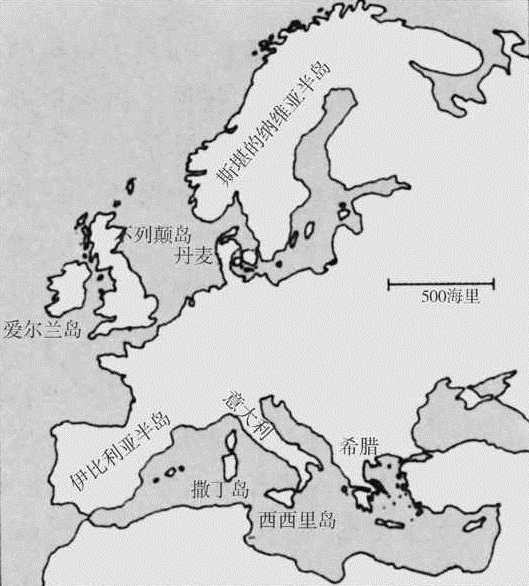

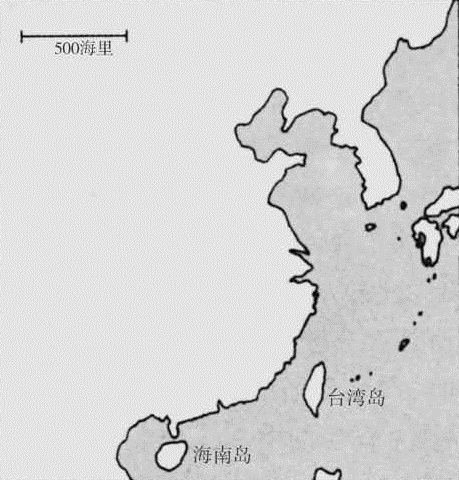

Hence the real problem in understanding China's loss of political and technological preeminence to Europe is to understand China's chronic unity and Europe's chronic disunity. The answer is again suggested by maps (see Backmatter). Europe has a highly indented coastline, with five large peninsulas that approach islands in their isolation, and all of which evolved independent languages, ethnic groups, and governments: Greece, Italy, Iberia, Denmark, and Norway / Sweden. China's coastline is much smoother, and only the nearby Korean Peninsula attained separate importance. Europe has two islands (Britain and Ireland) sufficiently big to assert their political independence and to maintain their own languages and ethnicities, and one of them (Britain) big and close enough to become a major independent European power. But even China's two largest islands, Taiwan and Hainan, have each less than half the area of Ireland; neither was a major independent power until Taiwan's emergence in recent decades; and Japan's geographic isolation kept it until recently much more isolated politically from the Asian mainland than Britain has been from mainland Europe. Europe is carved up into independent linguistic, ethnic, and political units by high mountains (the Alps, Pyrenees, Carpathians, and Norwegian border mountains), while China's mountains east of the Tibetan plateau are much less formidable barriers. China's heartland is bound together from east to west by two long navigable river systems in rich alluvial valleys (the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers), and it is joined from north to south by relatively easy connections between these two river systems (eventually linked by canals). As a result, China very early became dominated by two huge geographic core areas of high productivity, themselves only weakly separated from each other and eventually fused into a single core. Europe's two biggest rivers, the Rhine and Danube, are smaller and connect much less of Europe. Unlike China, Europe has many scattered small core areas, none big enough to dominate the others for long, and each the center of chronically independent states.

因此,了解了中国把政治和技术的卓越地位让给欧洲这方面的真正问题,就是了解了中国的长期统一和欧洲的长期分裂的问题。答案又一次用地图表示出来(见下图)。欧洲海岸线犬牙交错,它有5大半岛,每个半岛都近似孤悬海中的海岛,在所有这些半岛上形成了独立的语言、种族和政府:希腊、意大利、伊比利亚半岛、丹麦和挪威/瑞典。中国的海岸线则平直得多,只有附近的朝鲜半岛才获得了作为单独岛屿的重要性。欧洲有两个岛(大不列颠岛和爱尔兰岛),它们的面积都相当大,足以维护自己的政治独立和保持自己的语言和种族特点,其中的一个岛(大不列颠岛)因为面积大,离欧洲大陆又近,所以成了一个重要的欧洲独立强国。但即使是中国的两个最大的岛——台湾岛和海南岛,面积都不到爱尔兰岛的一半,这两个岛都不是重要独立的政体;而日本在地理上的孤立地位使它在现代以前一直处于与亚洲大陆的政治隔绝状态,其程度远远超过了大不列颠与欧洲大陆的政治隔绝状态。欧洲被一些高山(阿尔卑斯山脉、比利牛斯山脉、喀尔巴阡山脉和挪威边界山脉)分割成一些独立的语言、种族和政治单位,而中国在西藏高原以东的山脉则不是那样难以克服的障碍。中国的中心地带从东到西被肥沃的冲积河谷中两条可通航的水系(长江和黄河)连接了起来,从南到北又由于这两大水系(最后有运河连接)之间比较方便的车船联运而成为一体。因此,中国很早就受到了地域广阔的两个高生产力核心地区的决定性影响,而这两个地区本来彼此只有微不足道的阻隔,后来竟合并为一个中心。欧洲的两条最大的河流——莱茵河与多瑙河则比较小,在欧洲流经的地方也少得多。与中国不同,欧洲有许多分散的小的核心地区,没有一个大到足以对其他核心地区产生长期的决定性影响,而每一个地区又都是历史上一些独立国家的中心。

Comparison of the coastlines of China and of Europe, drawn to the same scale. Note that Europe's is much more indented and includes more large peninsulas and two large islands.

中国海岸线与欧洲海岸线的比较,按相同比例绘制。请注意:欧洲的海岸线曲折得多,并且包括更多的大半岛和两个大海岛。

Once China was finally unified, in 221 B.C., no other independent state ever had a chance of arising and persisting for long in China. Although periods of disunity returned several times after 221 B.C., they always ended in reunification. But the unification of Europe has resisted the efforts of such determined conquerors as Charlemagne, Napoleon, and Hitler; even the Roman Empire at its peak never controlled more than half of Europe's area.

中国一旦于公元前221年最后获得统一,就再没有任何其他的独立国家有可能在中国出现并长期存在下去。虽然在公元前221年后有几个时期出现了分裂局面,但最后总是重新归于统一。但欧洲的统一就连查理曼 [3]、拿破仑和希特勒这些下定决心的征服者都无能为力;甚至罗马帝国在其鼎盛时期所控制的地区也没有超过欧洲的一半。

Thus, geographic connectedness and only modest internal barriers gave China an initial advantage. North China, South China, the coast, and the interior contributed different crops, livestock, technologies, and cultural features to the eventually unified China. For example, millet cultivation, bronze technology, and writing arose in North China, while rice cultivation and cast-iron technology emerged in South China. For much of this book I have emphasized the diffusion of technology that takes place in the absence of formidable barriers. But China's connectedness eventually became a disadvantage, because a decision by one despot could and repeatedly did halt innovation. In contrast, Europe's geographic balkanization resulted in dozens or hundreds of independent, competing statelets and centers of innovation. If one state did not pursue some particular innovation, another did, forcing neighboring states to do likewise or else be conquered or left economically behind. Europe's barriers were sufficient to prevent political unification, but insufficient to halt the spread of technology and ideas. There has never been one despot who could turn off the tap for all of Europe, as of China.

因此,地理上的四通八达和非常一般的内部障碍,使中国获得了一种初始的有利条件。华北、华南、沿海地区和内陆的不同作物、牲畜、技术和文化特点,为中国的最后统一作出了贡献。例如,黍的栽培、青铜技术和文字出现在华北,而水稻的栽培和铸铁技术则出现在华南。我用本书的很大篇幅着重讨论了在没有难以克服的障碍的情况下技术的传播问题。但中国在地理上的四通八达最后却成了一个不利条件,某个专制君主的一个决定就能使改革创新半途而废,而且不止一次地这样做了。相比之下,欧洲在地理上的分割形成了几十个或几百个独立的、相互竞争的小国和发明创造的中心。如果某个国家没有去追求某种改革创新,另一个国家会去那样做的,从而迫使邻国也这样去做,否则就会被征服或在经济上处于落后地位。欧洲的地理障碍足以妨碍政治上的统一,但还不足以使技术和思想的传播停止下来。欧洲还从来没有哪一个专制君王能够像在中国那样切断整个欧洲的创造源泉。

These comparisons suggest that geographic connectedness has exerted both positive and negative effects on the evolution of technology. As a result, in the very long run, technology may have developed most rapidly in regions with moderate connectedness, neither too high nor too low. Technology's course over the last 1,000 years in China, Europe, and possibly the Indian subcontinent exemplifies those net effects of high, moderate, and low connectedness, respectively.

这些比较表明,地理上的四通八达对技术的发展既有积极的影响,也有消极的影响。因此,从长远来看,在地理便利程度不太高也不太低而是中等适度的地区,技术可能发展得最快。中国、欧洲,可能还有印度次大陆的过去1000多年的技术发展过程便是例子,它分别表明了高、中、低3种不同程度的地理便利条件所产生的实际效果。

Naturally, additional factors contributed to history's diverse courses in different parts of Eurasia. For instance, the Fertile Crescent, China, and Europe differed in their exposure to the perennial threat of barbarian invasions by horse-mounted pastoral nomads of Central Asia. One of those nomad groups (the Mongols) eventually destroyed the ancient irrigation systems of Iran and Iraq, but none of the Asian nomads ever succeeded in establishing themselves in the forests of western Europe beyond the Hungarian plains. Environmental factors also include the Fertile Crescent's geographically intermediate location, controlling the trade routes linking China and India to Europe, and China's more remote location from Eurasia's other advanced civilizations, making China a gigantic virtual island within a continent. China's relative isolation is especially relevant to its adoption and then rejection of technologies, so reminiscent of the rejections on Tasmania and other islands (Chapters 13 and 15). But this brief discussion may at least indicate the relevance of environmental factors to smaller-scale and shorter-term patterns of history, as well as to history's broadest pattern.

当然,还有一些因素也促成了欧亚大陆不同地区的不同的历史进程。例如,长期以来,新月沃地、中国和欧洲一直受到中亚草原上骑马的游牧民族野蛮入侵的威胁,但受到威胁的程度有所不同。这些游牧民族中有一支(蒙古人)终于破坏了伊朗和伊拉克的古代灌溉系统,但亚洲游牧民族中没有一支成功地在匈牙利平原以远的欧洲西部的森林地带站稳脚根。环境因素还包括:新月沃地的居间的地理位置,控制了把中国和印度与欧洲连接起来的贸易路线,以及中国距离欧亚大陆其他先进的文明国家路途遥远,使中国实际上成为一个大陆内的一个巨大的孤岛。中国的相对孤立状态与它先是采用技术后来又排斥技术这种做法有着特别重要的关系,这使人想起了塔斯马尼亚岛和其他岛屿排斥技术的情形(第十三章和第十五章)。不过,这一简略的讨论至少可以表明,环境因素不但与历史的最广泛模式有关,而且也与较小规模和较短时期的历史模式有关。

The histories of the Fertile Crescent and China also hold a salutary lesson for the modern world: circumstances change, and past primacy is no guarantee of future primacy. One might even wonder whether the geographical reasoning employed throughout this book has at last become wholly irrelevant in the modern world, now that ideas diffuse everywhere instantly on the Internet and cargo is routinely airfreighted overnight between continents. It might seem that entirely new rules apply to competition between the world's peoples, and that as a result new powers are emerging—such as Taiwan, Korea, Malaysia, and especially Japan.

新月沃地和中国的历史还为现代世界留下了一个有益的教训:环境改变了,过去是第一并不能保证将来也是第一。人们甚至会怀疑,本书从头到尾所运用的地理学推论在现代世界上是否终于变得毫不相干,因为思想可以在因特网上立即向四处传播,而货物照例可以一下子从一个洲空运到另一个洲。看来,对全世界各民族之间的竞争已实行了一些全新的规则,结果,像朝鲜、马来西亚,尤其是日本这些新的力量出现了。

On reflection, though, we see that the supposedly new rules are just variations on the old ones. Yes, the transistor, invented at Bell Labs in the eastern United States in 1947, leapt 8,000 miles to launch an electronics industry in Japan—but it did not make the shorter leap to found new industries in Zaire or Paraguay. The nations rising to new power are still ones that were incorporated thousands of years ago into the old centers of dominance based on food production, or that have been repopulated by peoples from those centers. Unlike Zaire or Paraguay, Japan and the other new powers were able to exploit the transistor quickly because their populations already had a long history of literacy, metal machinery, and centralized government. The world's two earliest centers of food production, the Fertile Crescent and China, still dominate the modern world, either through their immediate successor states (modern China), or through states situated in neighboring regions influenced early by those two centers (Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and Europe), or through states repopulated or ruled by their overseas emigrants (the United States, Australia, Brazil). Prospects for world dominance of sub-Saharan Africans, Aboriginal Australians, and Native Americans remain dim. The hand of history's course at 8000 B.C. lies heavily on us.

然而,仔细想来,我们发现,这些所谓的新规则不过是旧规则的改头换面而已。不错,1947年美国东部贝尔实验室发明的晶体管,跃进8000英里到日本去开创了电子工业——但它却没有跃进得近一些到扎伊尔或巴拉圭去建立新的工业。一跃而成为新兴力量的国家,仍然是几千年前就已被吸收进旧有的以粮食生产为基础的最高权力中心的那些国家,要不就是由来自这些中心的民族重新殖民的那些国家。与扎伊尔或巴拉圭不同,日本和其他新兴力量之所以能够迅速利用晶体管,是因为它们的国民已在文字、金属机械和中央集权的政府方面有了悠久的历史。世界上两个最早的粮食生产中心——新月沃地和中国仍然支配着现代世界,或者是通过它们的一脉相承的国家(现代中国),或者是通过位于很早就受到这两个中心影响的邻近地区内的一些国家(日本、朝鲜、马来西亚和欧洲),或者是通过由它们的海外移民重新殖民或统治的那些国家(美国、澳大利亚、巴西)。撒哈拉沙漠以南的非洲人、澳大利亚土著和美洲印第安人支配世界的前景仍然显得黯淡无光。公元前8000年时的历史进程之手仍然在紧紧抓住我们。

AMONG OTHER FACTORS relevant to answering Yali's question, cultural factors and influences of individual people loom large. To take the former first, human cultural traits vary greatly around the world. Some of that cultural variation is no doubt a product of environmental variation, and I have discussed many examples in this book. But an important question concerns the possible significance of local cultural factors unrelated to the environment. A minor cultural feature may arise for trivial, temporary local reasons, become fixed, and then predispose a society toward more important cultural choices, as is suggested by applications of chaos theory to other fields of science. Such cultural processes are among history's wild cards that would tend to make history unpredictable.

与回答耶利的问题有关的其他因素中,文化因素与个别民族的影响显得更加突出。先说文化因素。全世界人类文化的特点差异很大。有些文化差异无疑是环境差异的产物,我在本书中已经讨论过许多这方面的例子。但有一个重要的问题涉及与环境无关的当地文化因素可能具有的重要意义。一种次要的文化因素可能由于当地一时的微不足道的原因而产生了,但一经产生就变得确然不移,从而使社会易于接受一些更重要的文化选择,就像把混沌理论运用于其他科学领域所表明的那样。这种文化过程属于历史的未知因素,而正是这些因素往往会使历史变得不可预测。

As one example, I mentioned in Chapter 13 the QWERTY keyboard for typewriters. It was adopted initially, out of many competing keyboard designs, for trivial specific reasons involving early typewriter construction in America in the 1860s, typewriter salesmanship, a decision in 1882 by a certain Ms. Longley who founded the Shorthand and Typewriter Institute in Cincinnati, and the success of Ms. Longley's star typing pupil Frank McGurrin, who thrashed Ms. Longley's non-QWERTY competitor Louis Taub in a widely publicized typing contest in 1888. The decision could have gone to another keyboard at any of numerous stages between the 1860s and the 1880s; nothing about the American environment favored the QWERTY keyboard over its rivals. Once the decision had been made, though, the QWERTY keyboard became so entrenched that it was also adopted for computer keyboard design a century later. Equally trivial specific reasons, now lost in the remote past, may have lain behind the Sumerian adoption of a counting system based on 12 instead of 10 (leading to our modern 60-minute hour, 24-hour day, 12-month year, and 360-degree circle), in contrast to the widespread Mesoamerican counting system based on 20 (leading to its calendar using two concurrent cycles of 260 named days and a 365-day year).

作为一个例子,我曾在第十三章提到标准打字机键盘问题。在许多参与竞争的键盘设计中,这种标准键盘之所以能脱颖而出并开始被人采用,是由于一些微不足道的具体原因,如美国19世纪60年代早期的打字机制造技术,打字机的促销手段,一个在辛辛那提创建速写和打字学院、名叫朗利的女士于1882年作出的一个决定,以及朗利女士的杰出的打字学生弗兰克·麦克格林所取得的胜利,因为他于1888年的一次广为宣传的打字比赛中彻底击败了朗利女士的使用非标准键盘打字机的参赛对手路易斯·陶布。那个决定可能有助于从19世纪60年代到80年代无数阶段的任何一个阶段上发明出来的另一种打字机键盘;而美国当时的环境也没有任何因素只有利于标准打字机键盘而不利于它的竞争对手。然而,决定一经作出,标准打字机键盘就获得了牢固的地位,以致在一个世纪后又在计算机键盘设计中得到采用。同样微不足道的一些具体原因,由于年深日久现在已不可追寻,但也许正是这些原因使苏美尔人采用了12进制运算系统而没有采用10进制运算系统(12进制运算系统产生了我们现代的60分钟一小时、24小时一天、12个月一年和圆周360度),而中美洲普遍使用的运算系统则是20进制(产生了它的使用两个并行周期的历法,一个周期有260天,每天都有一个名称,一个周期是一年有365天)。

Those details of typewriter, clock, and calendar design have not affected the competitive success of the societies adopting them. But it is easy to imagine how they could have. For example, if the QWERTY keyboard of the United States had not been adopted elsewhere in the world as well—say, if Japan or Europe had adopted the much more efficient Dvorak keyboard—that trivial decision in the 19th century might have had big consequences for the competitive position of 20th-century American technology.

关于打字机、时钟和历法设计的这些细节并没有妨碍采用它们的社会在竞争中取得成功。但我们很容易想象出它们可能会产生的妨碍。例如,如果美国的打字机标准键盘都没有被世界上其他地方所采用——譬如说,如果日本或欧洲采用了效率高得多的德伏夏克键盘——那么,这个在19世纪作出的微不足道的决定,对于20世纪美国技术的竞争地位可能产生巨大的影响。

Similarly, a study of Chinese children suggested that they learn to write more quickly when taught an alphabetic transcription of Chinese sounds (termed pinyin) than when taught traditional Chinese writing, with its thousands of signs. It has been suggested that the latter arose because of their convenience for distinguishing the large numbers of Chinese words possessing differing meanings but the same sounds (homophones). If so, the abundance of homophones in the Chinese language may have had a large impact on the role of literacy in Chinese society, yet it seems unlikely that there was anything in the Chinese environment selecting for a language rich in homophones. Did a linguistic or cultural factor account for the otherwise puzzling failure of complex Andean civilizations to develop writing? Was there anything about India's environment predisposing toward rigid socioeconomic castes, with grave consequences for the development of technology in India? Was there anything about the Chinese environment predisposing toward Confucian philosophy and cultural conservatism, which may also have profoundly affected history? Why was proselytizing religion (Christianity and Islam) a driving force for colonization and conquest among Europeans and West Asians but not among Chinese?

同样,对中国儿童的研究表明,如果教会他们用字母给汉语语音标音(称为拼音),他们就能比学习有几千个符号的传统的中国文字更快地学会写字。有人说,传统的中国文字的出现是因为它们便于区别大量的意义不同但发音相同的汉语词(同音异义词)。果真如此,那么汉语中丰富的同音异义词可能对中国社会中识字的作用产生了巨大的影响,但如认为中国环境中存在某种因素促使选择了一种同音异义词丰富的语言,似乎也未必如此。复杂的安第斯山文明没有能发明出文字,这是否可以用某种语言因素或文化因素来予以解释?否则就令人难以理解了。印度的环境中是否存在某种因素,使它容易接受涉及社会经济地位的种姓制度,而不顾对印度技术发展所造成的严重后果?中国的环境中是否存在某种因素,使它容易接受可能也对历史产生深刻影响的儒家哲学和文化保守主义?为什么普度众生的宗教(基督教和伊斯兰教)在欧洲人和西亚人中而不是在中国人中成为殖民和征服的动力?

These examples illustrate the broad range of questions concerning cultural idiosyncrasies, unrelated to environment and initially of little significance, that might evolve into influential and long-lasting cultural features. Their significance constitutes an important unanswered question. It can best be approached by concentrating attention on historical patterns that remain puzzling after the effects of major environmental factors have been taken into account.

这些例子说明了涉及文化特质的范围广泛的问题。这些文化特质与环境无关,而且在开始时也几乎没有什么重要的意义,但它们可能逐步形成有影响的历久不衰的文化特点。它们的重要意义在于提出了一个重要的没有得到回答的问题。解决这个问题的最佳途径,就是集中注意力于那些在考虑了主要环境因素的影响之后仍然令人费解的历史模式。

WHAT ABOUT THE effects of idiosyncratic individual people? A familiar modern example is the narrow failure, on July 20, 1944, of the assassination attempt against Hitler and of a simultaneous uprising in Berlin. Both had been planned by Germans who were convinced that the war could not be won and who wanted to seek peace then, at a time when the eastern front between the German and Russian armies still lay mostly within Russia's borders. Hitler was wounded by a time bomb in a briefcase placed under a conference table; he might have been killed if the case had been placed slightly closer to the chair where he was sitting. It is likely that the modern map of Eastern Europe and the Cold War's course would have been significantly different if Hitler had indeed been killed and if World War II had ended then.

具有特质的个人的影响又是怎样的呢?一个为人们所熟悉的例子是1944年6月20日行刺希特勒的图谋和同时在柏林举行起义的计划功败垂成。这两件事都是德国人策划的,他们深信不可能打赢战争,于是就在德俄两国军队的东部战线仍然主要在俄国境内时,他们希望寻求和平。希特勒被放在会议桌下的公文包里的一颗定时炸弹炸伤;如果公文包放得稍稍靠近希特勒的坐椅,他也许就被炸死了。如果希特勒真的被炸死,如果第二次世界大战在当时结束了,那么现代的东欧地图和冷战进程可能就大为改观了。

Less well known but even more fateful was a traffic accident in the summer of 1930, over two years before Hitler's seizure of power in Germany, when a car in which he was riding in the “death seat” (right front passenger seat) collided with a heavy trailer truck. The truck braked just in time to avoid running over Hitler's car and crushing him. Because of the degree to which Hitler's psychopathology determined Nazi policy and success, the form of an eventual World War II would probably have been quite different if the truck driver had braked one second later.

不大为人所知但甚至更加重大的事件是1930年夏天的一次交通事故。那是希特勒在德国夺权之前两年多发生的事。当时他坐在一辆轿车的“死亡座”上(前排右边的乘客座位上),他的车和一辆满载的有挂车的卡车相撞。幸亏卡车及时刹车,才没有碾过希特勒的座车把它压死。鉴于希特勒的精神机能障碍在决定纳粹的政策与成功方面所达到的程度,如果那个卡车司机晚一秒钟刹车,即使万一发生了第二次世界大战,情况大概也会十分不同。

One can think of other individuals whose idiosyncrasies apparently influenced history as did Hitler's: Alexander the Great, Augustus, Buddha, Christ, Lenin, Martin Luther, the Inca emperor Pachacuti, Mohammed, William the Conqueror, and the Zulu king Shaka, to name a few. To what extent did each really change events, as opposed to “just” happening to be the right person in the right place at the right time? At the one extreme is the view of the historian Thomas Carlyle: “Universal history, the history of what man [sic] has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here.” At the opposite extreme is the view of the Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck, who unlike Carlyle had long firsthand experience of politics' inner workings: “The statesman's task is to hear God's footsteps marching through history, and to try to catch on to His coattails as He marches past.”

我们还可以想出其他一些个人,他们的特质和希特勒的特质一样显然对历史产生了影响,他们是:亚历山大大帝、奥古斯都 [4]、佛陀 [5]、基督、列宁、马丁·路德、印加帝国皇帝帕查库蒂、穆罕默德 [6]、征服者威廉 [7]和祖鲁国王沙卡,就举这么几个。他们中的每一个人究竟在多大程度上真正改变了事件的进程,而不“只”是恰巧最合适的人在最合适的时间出现在最合适的地点?一个极端是历史学家托马斯·卡莱尔 [8]的观点:“世界的历史就是人〔原文如此〕在这个世界上所取得的成就的历史,实际上就是在这个世界上活动的伟人的历史。”另一个极端是普鲁士政治家奥托·冯·俾斯麦的观点,他与卡莱尔不同,他对政治的内幕活动具有长期的直接经验,他说:“政治家的任务就是倾听上帝在历史上走过的脚步声,并且当他在身旁经过时努力抓住他的上衣的后下摆,跟他一起前进。”

Like cultural idiosyncrasies, individual idiosyncrasies throw wild cards into the course of history. They may make history inexplicable in terms of environmental forces, or indeed of any generalizable causes. For the purposes of this book, however, they are scarcely relevant, because even the most ardent proponent of the Great Man theory would find it difficult to interpret history's broadest pattern in terms of a few Great Men. Perhaps Alexander the Great did nudge the course of western Eurasia's already literate, food-producing, iron-equipped states, but he had nothing to do with the fact that western Eurasia already supported literate, food-producing, iron-equipped states at a time when Australia still supported only nonliterate hunter-gatherer tribes lacking metal tools. Nevertheless, it remains an open question how wide and lasting the effects of idiosyncratic individuals on history really are.

同文化的特质一样,个人的特质也是历史进程中的未知因素。无论是从环境的力量来看,还是事实上从任何可以归纳起来的原因来看,个人的特质都会使历史变得无法说明。然而,就本书的论题来说,所谓个人的特质几乎是毫不相干的,因为即使是伟人理论的最热情的支持者也觉得难以用几个伟人来解释历史最广泛的模式。也许,亚历山大大帝的确轻轻推动了一下欧亚大陆西部已经有了文字、粮食生产和铁器的国家的历史进程,但他与这样的事实毫无关系:当澳大利亚还仍然维持着没有文字、没有金属工具的狩猎采集部落时,欧亚大陆西部已经有了有文字的、从事粮食生产和使用铁器的国家了。不过,具有某些特质的个人的历史的影响究竟有多广泛和多持久,这仍然是一个可以讨论的问题。

THE DISCIPLINE OF history is generally not considered to be a science, but something closer to the humanities. At best, history is classified among the social sciences, of which it rates as the least scientific. While the field of government is often termed “political science” and the Nobel Prize in economics refers to “economic science,” history departments rarely if ever label themselves “Department of Historical Science.” Most historians do not think of themselves as scientists and receive little training in acknowledged sciences and their methodologies. The sense that history is nothing more than a mass of details is captured in numerous aphorisms: “History is just one damn fact after another,” “History is more or less bunk,” “There is no law of history any more than of a kaleidoscope,” and so on.

历史这门学科一般认为不是一门科学,而是比较接近人文学科。历史最多可以划归社会科学,而在社会科学中,它又被列为最少科学性的一种。虽然研究政治的专业常常被称为“政治学”,而诺贝尔经济学奖也指称“经济学”,但历史系即使有也很少称自己为“历史学系”。大多数历史学家并不把自己看作科学家,也很少在一些公认的科学领域及其方法论方面受过训练。在许多警句中都有历史不过是一大堆细节这种认识:“历史不过是一个又一个讨厌的事实”,“历史或多或少都是骗人的鬼话”,“历史和万花筒一样毫无规律可言”,等等。

One cannot deny that it is more difficult to extract general principles from studying history than from studying planetary orbits. However, the difficulties seem to me not fatal. Similar ones apply to other historical subjects whose place among the natural sciences is nevertheless secure, including astronomy, climatology, ecology, evolutionary biology, geology, and paleontology. People's image of science is unfortunately often based on physics and a few other fields with similar methodologies. Scientists in those fields tend to be ignorantly disdainful of fields to which those methodologies are inappropriate and which must therefore seek other methodologies—such as my own research areas of ecology and evolutionary biology. But recall that the word “science” means “knowledge” (from the Latin scire, “to know,” and scientia, “knowledge”), to be obtained by whatever methods are most appropriate to the particular field. Hence I have much empathy with students of human history for the difficulties they face.

无可否认,从研究历史中去获得普遍原则,要比从研究行星轨道中去获得普遍原则来得困难。然而,在我看来,这些困难并不是决定性的。其他一些历史学科,包括天文学、气候学、生态学、演化生物学、地质学和古生物学,虽然也碰到了同样的困难,但它们在自然科学中的地位却是牢固的。不幸的是,人们对历史的概念常常是以物理学和其他几个运用同样方法的领域为基础的。这些领域的科学家往往由于无知而对某些领域不屑一顾,因为对这些领域这些方法是不适用的,因此必须寻找其他方法——例如我自己的研究领域生态学和演化生物学就是如此。不过,请记住:“science”(科学)这个词的意思是“knowledge”(知识)(来自拉丁语的scire即“toknow”〔知道〕和scientia即“knowledge”〔知识〕),而知识是要通过任何对特定领域最合适的方法来获得的。因此,我对研究人类历史的人所面临的困难非常同情。

Historical sciences in the broad sense (including astronomy and the like) share many features that set them apart from nonhistorical sciences such as physics, chemistry, and molecular biology. I would single out four: methodology, causation, prediction, and complexity.

广义的历史科学(包括天文学之类的学科)具有许多共同的特点,把它们同非历史科学如物理学、化学和分子生物学之类区别开来。我可以挑出4个方面的差别来讨论:方法、因果关系、预测和复杂程度。

In physics the chief method for gaining knowledge is the laboratory experiment, by which one manipulates the parameter whose effect is in question, executes parallel control experiments with that parameter held constant, holds other parameters constant throughout, replicates both the experimental manipulation and the control experiment, and obtains quantitative data. This strategy, which also works well in chemistry and molecular biology, is so identified with science in the minds of many people that experimentation is often held to be the essence of the scientific method. But laboratory experimentation can obviously play little or no role in many of the historical sciences. One cannot interrupt galaxy formation, start and stop hurricanes and ice ages, experimentally exterminate grizzly bears in a few national parks, or rerun the course of dinosaur evolution. Instead, one must gain knowledge in these historical sciences by other means, such as observation, comparison, and so-called natural experiments (to which I shall return in a moment).

在物理学中,获得知识的主要方法是实验室实验,人们通过实验来处理结果有疑问的参数,用被认为恒定的参数来进行平行的对照实验,保留始终恒定的参数,复制对实验的处理和对照试验,并获得定量数据。这种方法在化学和分子生物学中也是十分有用的,它在许多人的思想里成了科学本身,因此实验常常被认为是科学方法的本质。但在许多历史科学中,实验室实验显然只能起很小的作用,或者完全不起作用。人不能阻碍银河系的形成,不能发动和制止飓风和冰河期,不能用实验的方法使几个国家公园里的灰熊灭绝,也不能再现恐龙的演化过程。人只能用别的方法获得这些历史科学方面的知识,如观察、比较和所谓的自然实验(这一点我回头再来讨论)。

Historical sciences are concerned with chains of proximate and ultimate causes. In most of physics and chemistry the concepts of “ultimate cause,” “purpose,” and “function” are meaningless, yet they are essential to understanding living systems in general and human activities in particular. For instance, an evolutionary biologist studying Arctic hares whose fur color turns from brown in summer to white in winter is not satisfied with identifying the mundane proximate causes of fur color in terms of the fur pigments' molecular structures and biosynthetic pathways. The more important questions involve function (camouflage against predators?) and ultimate cause (natural selection starting with an ancestral hare population with seasonally unchanging fur color?). Similarly, a European historian is not satisfied with describing the condition of Europe in both 1815 and 1918 as having just achieved peace after a costly pan-European war. Understanding the contrasting chains of events leading up to the two peace treaties is essential to understanding why an even more costly pan-European war broke out again within a few decades of 1918 but not of 1815. But chemists do not assign a purpose or function to a collision of two gas molecules, nor do they seek an ultimate cause for the collision.

历史科学研究的是一连串的直接原因和终极原因。在大部分物理学和化学中,“终极原因”、“目的”和“功能”这些概念是没有意义的,但它们对于了解一般的生命系统尤其是人类的活动,是至关重要的。例如,北极兔的毛色在夏天是棕色,到冬天就变为白色,但研究北极兔的演化生物学家并不满足于弄清楚从毛色素的分子结构和生物合成途径的角度来研究的毛色的普通直接原因。更重要的问题是功能(逃避捕食者的保护色?)和终极原因(从没有季节性毛色变化的祖代兔群开始的自然选择?)。同样,一个欧洲历史学家不会满足于把1815年和1918年欧洲的状况 [9]描写为经过代价巨大的泛欧战争之后刚刚获得了和平。了解形成对比的一连串导致两个和平条约 [10]的事件,对于了解为什么1918年后而不是1815年后的几十年内又一次爆发了代价甚至更大的泛欧战争是必不可少的。但化学家并不为两个气体分子的碰撞规定某种目的或功能,他们也不会去寻找这种碰撞的终极原因。

Still another difference between historical and nonhistorical sciences involves prediction. In chemistry and physics the acid test of one's understanding of a system is whether one can successfully predict its future behavior. Again, physicists tend to look down on evolutionary biology and history, because those fields appear to fail this test. In historical sciences, one can provide a posteriori explanations (e.g., why an asteroid impact on Earth 66 million years ago may have driven dinosaurs but not many other species to extinction), but a priori predictions are more difficult (we would be uncertain which species would be driven to extinction if we did not have the actual past event to guide us). However, historians and historical scientists do make and test predictions about what future discoveries of data will show us about past events.

历史科学和非历史科学之间的另一个差异就是预测。在化学和物理学中,测验一个人是否了解某个系统就是看他能否成功地预测这个系统的未来变化。另外,物理学家还往往看不起演化生物学和历史,因为这两个领域似乎通不过这种测验。在历史科学中,人们可以提供一种事后的解释(例如,为什么6600万年前一颗小行星对地球的撞击会使得恐龙灭绝,而没有使其他许多物种灭绝),而事前的预测就比较困难了(如果我们没有过去的实际情况作为指引,我们可能会无法确定哪些物种可能会招致灭绝)。然而,对于未来什么样的资料发现会告诉我们过去所发生的事,历史学家和历史科学家的确作出了并检验了一些预测。

The properties of historical systems that complicate attempts at prediction can be described in several alternative ways. One can point out that human societies and dinosaurs are extremely complex, being characterized by an enormous number of independent variables that feed back on each other. As a result, small changes at a lower level of organization can lead to emergent changes at a higher level. A typical example is the effect of that one truck driver's braking response, in Hitler's nearly fatal traffic accident of 1930, on the lives of a hundred million people who were killed or wounded in World War II. Although most biologists agree that biological systems are in the end wholly determined by their physical properties and obey the laws of quantum mechanics, the systems' complexity means, for practical purposes, that that deterministic causation does not translate into predictability. Knowledge of quantum mechanics does not help one understand why introduced placental predators have exterminated so many Australian marsupial species, or why the Allied Powers rather than the Central Powers won World War I.

历史系统的性质使预测的企图变得复杂了。对于这些性质,可以用几种不同的方法来加以描写。我们可以指出的是,人类社会和恐龙都是极其复杂的,它们的特点是具有大量的互相反馈的独立变数。结果,较低组织层次上的小小变化可能会引起较高层次上的突变。典型的例子就是1930年险些让希特勒送命的交通事故中,那个卡车司机的刹车反应对第二次世界大战中死伤的1亿人的生命的影响。虽然大多数生物学家都同意生物系统归根到底完全决定于它们的物理性质并服从量子力学的定律,但这些系统的复杂程度实际上意味着这种决定论的因果关系并不能转化为可预测性。量子力学的知识并不能帮助人理解为什么引进的有胎盘食肉动物消灭了那么多的澳大利亚有袋目动物,或者为什么获得第一次世界大战胜利的是协约国而不是同盟国。

Each glacier, nebula, hurricane, human society, and biological species, and even each individual and cell of a sexually reproducing species, is unique, because it is influenced by so many variables and made up of so many variable parts. In contrast, for any of the physicist's elementary particles and isotopes and of the chemist's molecules, all individuals of the entity are identical to each other. Hence physicists and chemists can formulate universal deterministic laws at the macroscopic level, but biologists and historians can formulate only statistical trends. With a very high probability of being correct, I can predict that, of the next 1,000 babies born at the University of California Medical Center, where I work, not fewer than 480 or more than 520 will be boys. But I had no means of knowing in advance that my own two children would be boys. Similarly, historians note that tribal societies may have been more likely to develop into chiefdoms if the local population was sufficiently large and dense and if there was potential for surplus food production than if that was not the case. But each such local population has its own unique features, with the result that chiefdoms did emerge in the highlands of Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, and Madagascar, but not in those of New Guinea or Guadalcanal.

每一条冰川,每一团星云,每一次飓风,每一个人类社会,每一个生物物种,甚至每一个个人和某个有性生殖物种的每一个细胞,都是独一无二的,因为它受到那么多的变数的影响,而且是由那么多的可变部分构成的。相比之下,对于物理学家的任何基本粒子和同位素以及化学家的任何分子来说,实际存在物的所有个体彼此都是完全相同的。因此,物理学家和化学家能够在宏观的层次上系统地阐述带有普遍性的决定论的规律,但生物学家和历史学家只能系统地阐述统计学上的趋势。我能以很高的正确概率预测,在我工作的加利福尼亚大学医学中心出生的下1000个婴儿中,男婴的数目不会少于480个,也不会多于520个。但我没有办法事先知道我自己的两个孩子会是男孩。同样,一些历史学家指出,如果当地的人口够多,密度也够大,如果存在发展剩余粮食生产的潜力,那么部落社会也许比不存在上述情况时更有可能发展成为酋长管辖地。但是,每一个这样的当地人口都有其自身的独一无二的特点,其结果是酋长管辖地在墨西哥、危地马拉、秘鲁和马达加斯加的高原地区出现了,但却没有在新几内亚或瓜达尔卡纳尔岛 [11]的高原地区出现。

Still another way of describing the complexity and unpredictability of historical systems, despite their ultimate determinacy, is to note that long chains of causation may separate final effects from ultimate causes lying outside the domain of that field of science. For example, the dinosaurs may have been exterminated by the impact of an asteroid whose orbit was completely determined by the laws of classical mechanics. But if there had been any paleontologists living 67 million years ago, they could not have predicted the dinosaurs' imminent demise, because asteroids belong to a field of science otherwise remote from dinosaur biology. Similarly, the Little Ice Age of A.D. 1300–1500 contributed to the extinction of the Greenland Norse, but no historian, and probably not even a modern climatologist, could have predicted the Little Ice Age.

历史系统尽管有其终极的确定性,但其复杂性和不可预测性是不待言的。描述这种复杂性和不可预测性的另一个办法就是指出,长长的一连串因果关系可能把最后结果同存在于那一科学领域之外的终极原因分开。例如,一颗小行星对地球的撞击可能导致了恐龙的灭绝,但那颗小行星的轨道却是完全由古典力学的定律决定的。但如果有古生物学家生活在6700万年前,他们也不可能预测到恐龙的灭亡迫在眉睫,因为小行星属于一个在其他方面都与恐龙生物学关系疏远的科学领域研究的对象。同样,公元1300年至1500年之间的小冰期也是格陵兰岛上古挪威人灭绝的部分原因,但没有哪个历史学家,也许甚至也没有哪一个现代气候学家能够预测到小冰期的到来。

THUS, THE DIFFICULTIES historians face in establishing cause-and-effect relations in the history of human societies are broadly similar to the difficulties facing astronomers, climatologists, ecologists, evolutionary biologists, geologists, and paleontologists. To varying degrees, each of these fields is plagued by the impossibility of performing replicated, controlled experimental interventions, the complexity arising from enormous numbers of variables, the resulting uniqueness of each system, the consequent impossibility of formulating universal laws, and the difficulties of predicting emergent properties and future behavior. Prediction in history, as in other historical sciences, is most feasible on large spatial scales and over long times, when the unique features of millions of small-scale brief events become averaged out. Just as I could predict the sex ratio of the next 1,000 newborns but not the sexes of my own two children, the historian can recognize factors that made inevitable the broad outcome of the collision between American and Eurasian societies after 13,000 years of separate developments, but not the outcome of the 1960 U.S. presidential election. The details of which candidate said what during a single televised debate in October 1960 could have given the electoral victory to Nixon instead of to Kennedy, but no details of who said what could have blocked the European conquest of Native Americans.

因此,历史学家在确定人类社会史的因果关系时所碰到的困难,大致上类似于天文学家、气候学家、生态学家、演化生物学家、地质学家和古生物学家所碰到的困难。这些领域的每一个领域都在不同程度上受到以下几个方面的困扰:不可能进行可复制的对照实验的介入,大量变数带来的复杂性,每一个系统因而变得独一无二,结果不可能系统地阐述普遍的规律,以及难以预测突现性质和未来变化。历史预测和其他历史科学的预测一样,在大的时空范围内最为适宜,因为这时无数小的时空范围内的独一无二的特点趋于平衡。正如我能预测下1000个新生婴儿的性别比例但却不能预测我自己两个孩子的性别那样,历史学家能够认识到使美洲和欧亚大陆社会在经过13000年的独立发展后发生碰撞所产生的广泛后果变得不可避免的因素,但却不能认识到1960年美国总统选择的后果。在1960年10月的一次电视辩论会上,哪个总统候选人说了些什么之类的细节,可能会使尼克松而不是肯尼迪获得选举的胜利,但却没有谁说了些什么之类的细节,可以阻挡欧洲人征服印第安人。

How can students of human history profit from the experience of scientists in other historical sciences? A methodology that has proved useful involves the comparative method and so-called natural experiments. While neither astronomers studying galaxy formation nor human historians can manipulate their systems in controlled laboratory experiments, they both can take advantage of natural experiments, by comparing systems differing in the presence or absence (or in the strong or weak effect) of some putative causative factor. For example, epidemiologists, forbidden to feed large amounts of salt to people experimentally, have still been able to identify effects of high salt intake by comparing groups of humans who already differ greatly in their salt intake; and cultural anthropologists, unable to provide human groups experimentally with varying resource abundances for many centuries, still study long-term effects of resource abundance on human societies by comparing recent Polynesian populations living on islands differing naturally in resource abundance. The student of human history can draw on many more natural experiments than just comparisons among the five inhabited continents. Comparisons can also utilize large islands that have developed complex societies in a considerable degree of isolation (such as Japan, Madagascar, Native American Hispaniola, New Guinea, Hawaii, and many others), as well as societies on hundreds of smaller islands and regional societies within each of the continents.

研究人类史的人怎样才能从其他历史科学的科学家们的经验中获益呢?有一个证明有用的方法就是比较法和所谓的自然实验。虽然无论是研究银河系形成的天文学家还是人类史家,都不可能在有控制的实验室实验中来处理他们的系统,但他们都可以利用自然实验,把一些因存在或不存在(或作用有强有弱的)某种推定的起因而不同的系统加以比较。例如,流行病学家虽然不可以在实验中使人服用大量的盐,但仍然能够通过比较在盐的摄入方面已经存在巨大差异的不同人群,来确定盐的高摄入量的影响;而文化人类学家虽然不能用实验在许多世纪中向不同的人群提供丰富程度不同的资源,但仍然能够通过比较生活在自然资源丰富程度不同的岛屿上的近代波利尼西亚人,来研究资源的丰富程度对人类社会的长期影响。研究人类史的人可以利用多得多的自然实验,而不只是限于比较5个有人居住的大陆。在进行比较时不但可以利用数以百计的较小岛屿上的社会和从每个大陆都能到达的区域性社会,而且也可以利用一些在相当孤立状态中发展了复杂社会的大岛(如日本、马达加斯加、美洲的伊斯帕尼奥拉岛、新几内亚、夏威夷和其他许多岛屿)。

Natural experiments in any field, whether in ecology or human history, are inherently open to potential methodological criticisms. Those include confounding effects of natural variation in additional variables besides the one of interest, as well as problems in inferring chains of causation from observed correlations between variables. Such methodological problems have been discussed in great detail for some of the historical sciences. In particular, epidemiology, the science of drawing inferences about human diseases by comparing groups of people (often by retrospective historical studies), has for a long time successfully employed formalized procedures for dealing with problems similar to those facing historians of human societies. Ecologists have also devoted much attention to the problems of natural experiments, a methodology to which they must resort in many cases where direct experimental interventions to manipulate relevant ecological variables would be immoral, illegal, or impossible. Evolutionary biologists have recently been developing ever more sophisticated methods for drawing conclusions from comparisons of different plants and animals of known evolutionary histories.

任何领域的自然实验,不管是生态领域的还是人类史领域的,生来就容易受到可能的方法论的批评。这些批评不但包括了从观察到的变数之间相互关系来推定因果关系链方面的问题,而且也包括了混淆除关系重大的变数外其他一些变数的自然变异的作用。这些方法论问题已为了某些历史科学而得到了详尽的讨论。特别是流行病学——通过比较不同的人群(通常用历史追溯研究法)来对人类疾病作出论断的科学——长期以来一直成功地运用正式的程序,来处理类似人类社会历史学家所碰到的问题。生态学家也十分注意自然实验问题,因为在许多情况下,用直接的实验介入法来处理相关的生态变量可能是不道德的、不合法的或不可能的,所以生态学家必须把自然实验作为一种方法来使用。演化生物学家近来也发展出一些更复杂的方法,根据对已知的演化史上的不同动植物的比较来作出结论。

In short, I acknowledge that it is much more difficult to understand human history than to understand problems in fields of science where history is unimportant and where fewer individual variables operate. Nevertheless, successful methodologies for analyzing historical problems have been worked out in several fields. As a result, the histories of dinosaurs, nebulas, and glaciers are generally acknowledged to belong to fields of science rather than to the humanities. But introspection gives us far more insight into the ways of other humans than into those of dinosaurs. I am thus optimistic that historical studies of human societies can be pursued as scientifically as studies of dinosaurs—and with profit to our own society today, by teaching us what shaped the modern world, and what might shape our future.

总之,我承认,了解人类的历史要比了解某些科学领域的问题困难得多,因为在这些科学领域里,历史是不重要的,起作用的个别变量也比较少。不过,有几个领域已经设计出一些用来分析历史问题的成功的方法。因此,人们普遍承认,对恐龙、星云和冰川的系统阐述属于自然科学领域,而不属于人文学科。但是内省的方法使我们对其他人的行为方式比对恐龙的行为方式产生了多得多的真知灼见。因此,我很乐观,对人类社会的历史研究可以科学地进行,就像对恐龙的研究一样——同时,使我们认识到是什么塑造了现代世界以及是什么可能塑造未来世界,因而使今天我们自己的社会从中获益。

注释:

1 希贾兹:或译汉志,原为阿拉伯半岛上最早的王国,现为沙特阿拉伯省名。——译者

2 宝船队:即明永乐3年(1405年)开始至明宣宗宣德年间(1431—1433年)由宦官郑和率领的远航西洋(当时称今加里曼丹至非洲之间的海洋为西洋)的船队,共出航7次(一说8次),前后共28年。——译者

3 查理曼(742?—814):即查理大帝,法兰克国王(768—814)、查理帝国皇帝(800—814,称查理一世),扩展疆土建成庞大帝国,加强集权统治,鼓励学术,兴建文化设施,使其宫廷成为繁荣学术的中心。——译者

4 奥古斯都:公元前63—公元14年,罗马帝国第一代皇帝(公元前27—公元14年),恺撒的继承人。——译者

5 佛陀:佛教徒对释迦牟尼的尊称。——译者

6 穆罕默德(570?—632):伊斯兰教创始人,生于麦加,自称安拉使者,在麦加城开始创立伊斯兰教(610),后在麦地那建立神权国家(622),基本上统一了阿拉伯半岛。——译者

7 征服者威廉:即威廉一世(1028?—1087),法国诺曼底公爵(1035—1087)、英国国王(1066—1087),在黑斯廷斯打败英王哈罗德二世,自立为王,引进封建主义和诺曼人习俗,并下令编制土地调查清册(《末日审判书》)。——译者

8 托马斯·卡莱尔(1795—1881):苏格兰散文作家和历史学家,写有《法国革命》、《论英雄、英雄崇拜和历史上的英雄事迹》等著作。——译者

9 1815年和1918年的欧洲状况:1815年6月,拿破仑在滑铁卢战败后决定退位,法兰西第一帝国告终;1918年第一次世界大战结束。——译者

10 两个和平条约:指1815年结束拿破仑战争的《维也纳条约》和1919年结束第一次世界大战的《凡尔赛和约》。——译者

11 瓜达尔卡纳尔岛:在西南太平洋,为所罗门群岛的一部分,第二次世界大战期间日、美两国曾激战于此。——译者