PART TWO

第二部分

THE RISE AND SPREAD OF FOOD PRODUCTION

粮食生产的出现和传播

CHAPTER 4

第四章

FARMER POWER

农民的力量

AS A TEENAGER, I SPENT THE SUMMER OF 1956 IN MONTANA, working for an elderly farmer named Fred Hirschy. Born in Switzerland, Fred had come to southwestern Montana as a teenager in the 1890s and proceeded to develop one of the first farms in the area. At the time of his arrival, much of the original Native American population of hunter-gatherers was still living there.

我十几岁时在蒙大拿度过了1956年的夏天,为一个名叫弗雷德·赫希奇的上了年纪的农民打工。弗雷德出生在瑞士,在19世纪90年代他十几岁时来到了蒙大拿的西南部,接着便办起了这一地区第一批农场中的一个。在他来到时,原来的以狩猎采集为生的美洲土著有许多仍然生活在那里。

My fellow farmhands were, for the most part, tough whites whose normal speech featured strings of curses, and who spent their weekdays working so that they could devote their weekends to squandering their week's wages in the local saloon. Among the farmhands, though, was a member of the Blackfoot Indian tribe named Levi, who behaved very differently from the coarse miners—being polite, gentle, responsible, sober, and well spoken. He was the first Indian with whom I had spent much time, and I came to admire him.

和我在一起干活的农场工人多半是体格健壮的白人,他们经常满口粗话,他们除周末外每天劳动,这样他们就可以在周末整天泡在当地的酒馆里花光一周的工资。然而,就在这些农场工人中,有一个名叫利瓦伊的黑脚族印第安人。此人的行为举止和粗野的矿工大不相同——他彬彬有礼,温文尔雅,做事负责,头脑清醒,善于辞令。他是第一个我与之一起度过许多时光的印第安人,我不由对他钦佩起来。

It was therefore a shocking disappointment to me when, one Sunday morning, Levi too staggered in drunk and cursing after a Saturday-night binge. Among his curses, one has stood out in my memory: “Damn you, Fred Hirschy, and damn the ship that brought you from Switzerland!” It poignantly brought home to me the Indians' perspective on what I, like other white schoolchildren, had been taught to view as the heroic conquest of the American West. Fred Hirschy's family was proud of him, as a pioneer farmer who had succeeded under difficult conditions. But Levi's tribe of hunters and famous warriors had been robbed of its lands by the immigrant white farmers. How did the farmers win out over the famous warriors?

一个星期日的早晨,利瓦伊在经过星期六夜晚的一番狂欢作乐之后,竟也醉步踉跄,满口脏话。因此,我感到震惊和失望。在他的那些骂人话中,有一句我一直记得非常清楚:“你他妈的弗雷德·赫希奇,他妈的那艘把你从瑞士带来的船!”过去,和其他白人小学生一样,我所受的教育是把对美洲的开发看作是英勇的征服行为,现在我深切感受到印第安人对这种行为的看法了。弗雷德·赫希奇的一家都以他为荣,因为他是在困难条件下取得成功的最早的农民。但是,利瓦伊的狩猎部落和著名战士的土地都被迁移来的白人农民抢走了。这些农民又是怎样战胜这些著名的战士的呢?

For most of the time since the ancestors of modern humans diverged from the ancestors of the living great apes, around 7 million years ago, all humans on Earth fed themselves exclusively by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants, as the Blackfeet still did in the 19th century. It was only within the last 11,000 years that some peoples turned to what is termed food production: that is, domesticating wild animals and plants and eating the resulting livestock and crops. Today, most people on Earth consume food that they produced themselves or that someone else produced for them. At current rates of change, within the next decade the few remaining bands of hunter-gatherers will abandon their ways, disintegrate, or die out, thereby ending our millions of years of commitment to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

自从现代人的祖先在大约700万年前从现在的类人猿的祖先分化出来后,地球上的所有人类大部分时间都是靠猎捕野兽和采集野生植物为生,就像19世纪黑脚族印第安人仍然在做的那样。只是在过去的11000年中,有些民族才转向所谓的粮食生产:就是说,驯化野生动植物,以因此而产生的牲畜和农作物为食。今天,地球上的大多数人吃他们自己生产的粮食或别人为他们生产的粮食。按照当前的变化速度,在今后10年内,剩下来的少数以狩猎采集为生的人群将会放弃他们的生活方式,发生解体或逐渐消失,从而结束我们几百万年来专以狩猎采集为生的生活方式。

Different peoples acquired food production at different times in prehistory. Some, such as Aboriginal Australians, never acquired it at all. Of those who did, some (for example, the ancient Chinese) developed it independently by themselves, while others (including ancient Egyptians) acquired it from neighbors. But, as we'll see, food production was indirectly a prerequisite for the development of guns, germs, and steel. Hence geographic variation in whether, or when, the peoples of different continents became farmers and herders explains to a large extent their subsequent contrasting fates. Before we devote the next six chapters to understanding how geographic differences in food production arose, this chapter will trace the main connections through which food production led to all the advantages that enabled Pizarro to capture Atahuallpa, and Fred Hirschy's people to dispossess Levi's (Figure 4.1).

不同部族在史前的不同时期学会了粮食生产。有些部族,如澳大利亚土著,却从来没有学会粮食生产。在那些学会粮食生产的部族中,有些(例如古代的中国人)是靠自己独立发展粮食生产的,而另一些(包括古代埃及人)则是从邻近部族学会粮食生产的。但是,我们将会看到,从间接的意义说,粮食生产是枪炮、病菌和钢铁发展的一个先决条件。因此,在不同大陆的族群是否或何时变成农民和牧人方面的地理差异,在很大程度上说明了他们以后截然不同的命运。在我们把下面6章专门用来弄清楚粮食生产方面的地理差异是怎样产生的之前,本章将查考一下一些主要的因果关系,因为粮食生产正是通过这种关系带来了所有使皮萨罗俘虏阿塔瓦尔帕和弗雷德·赫希奇的族人剥夺利瓦伊的族人的有利条件。

The first connection is the most direct one: availability of more consumable calories means more people. Among wild plant and animal species, only a small minority are edible to humans or worth hunting or gathering. Most species are useless to us as food, for one or more of the following reasons: they are indigestible (like bark), poisonous (monarch butterflies and death-cap mushrooms), low in nutritional value (jellyfish), tedious to prepare (very small nuts), difficult to gather (larvae of most insects), or dangerous to hunt (rhinoceroses). Most biomass (living biological matter) on land is in the form of wood and leaves, most of which we cannot digest.

第一个因果关系是最直接的因果关系:能够获得更多的可消耗的卡路里就意味着会有更多的人。在野生的动植物物种中,只有很少一部分可供人类食用,或值得猎捕或采集。多数动植物是不能用作我们的食物的,这有以下的一些原因:它们有的不能消化(如树皮),有的有毒(黑脉金斑蝶和鬼笔鹅膏——一种有毒蘑菇),有的营养价值低(水母),有的吃起来麻烦(很小的干果),有的采集起来困难(大多数昆虫的幼虫),有的猎捕起来危险(犀牛)。陆地上大多数生物量(活的生物物质)都是以木头和叶子的形态而存在的,而这些东西大多数我们都不能消化。

By selecting and growing those few species of plants and animals that we can eat, so that they constitute 90 percent rather than 0.1 percent of the biomass on an acre of land, we obtain far more edible calories per acre. As a result, one acre can feed many more herders and farmers—typically, 10 to 100 times more—than hunter-gatherers. That strength of brute numbers was the first of many military advantages that food-producing tribes gained over hunter-gatherer tribes.

通过对我们能够吃的那几种动植物的选择、饲养和种植,使它们构成每英亩土地上的生物量的90%而不是0.1%,我们就能从每英亩土地获得多得多的来自食物的卡路里。结果,每英亩土地就能养活多得多的牧人和农民——一般要比以狩猎采集为生的人多10倍到100倍。这些没有感情的数字所产生的力量,就是生产粮食的部落取得对狩猎采集部落的许多军事优势中的第一个优势。

In human societies possessing domestic animals, livestock fed more people in four distinct ways: by furnishing meat, milk, and fertilizer and by pulling plows. First and most directly, domestic animals became the societies' major source of animal protein, replacing wild game. Today, for instance, Americans tend to get most of their animal protein from cows, pigs, sheep, and chickens, with game such as venison just a rare delicacy. In addition, some big domestic mammals served as sources of milk and of milk products such as butter, cheese, and yogurt. Milked mammals include the cow, sheep, goat, horse, reindeer, water buffalo, yak, and Arabian and Bactrian camels. Those mammals thereby yield several times more calories over their lifetime than if they were just slaughtered and consumed as meat.

在饲养驯化动物的人类社会中,牲畜在4个不同的方面养活了更多的人:提供肉类、奶脂、肥料以及拉犁。最直接的是,家畜代替野生猎物而成为社会主要的动物蛋白来源。例如,今天的美国人通常从奶牛、猪、羊和鸡那里得到他们的大多数动物蛋白,而像鹿肉这样的野味则成了难得的美味佳肴。此外,一些驯化的大型哺乳动物则成了奶和诸如黄油、奶酪和酸奶之类奶制品的来源。产奶的哺乳动物包括母牛、绵羊、山羊、马、驯鹿、水牛、牦牛、阿拉伯单峰骆驼和中亚双峰骆驼,这些哺乳动物由此而产生的卡路里比它们被杀来吃肉所产生的卡路里要多几倍。

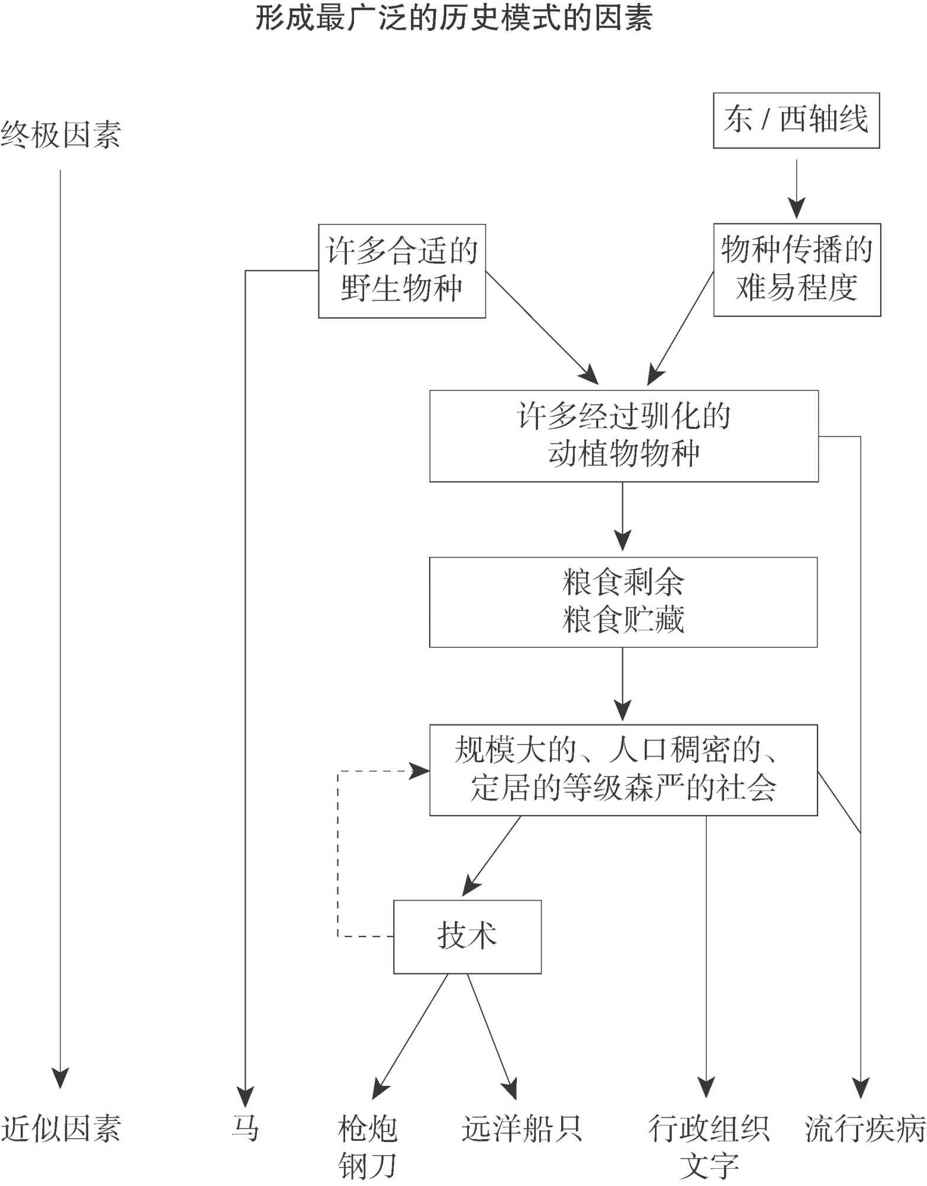

Figure 4.1. Schematic overview of the chains of causation leading up to proximate factors (such as guns, horses, and diseases) enabling some peoples to conquer other peoples, from ultimate factors (such as the orientation of continental axes). For example, diverse epidemic diseases of humans evolved in areas with many wild plant and animal species suitable for domestication, partly because the resulting crops and livestock helped feed dense societies in which epidemics could maintain themselves, and partly because the diseases evolved from germs of the domestic animals themselves.

图4.1略图概述从终极因素(如大陆轴线走向)通往使某些民族能够征服另一些民族的近似因素(如枪炮、马匹和疾病)的因果关系链。例如,人类的各种各样疾病是在有许多适于驯化的动植物物种的地区演化的,这一部分是由于生产出的农作物和饲养的牲畜帮助养活了使流行疾病得以保持的人口稠密的社会;一部分是由于这些疾病是从驯化的动物身上的病菌演化而来。

Big domestic mammals also interacted with domestic plants in two ways to increase crop production. First, as any modern gardener or farmer still knows by experience, crop yields can be greatly increased by manure applied as fertilizer. Even with the modern availability of synthetic fertilizers produced by chemical factories, the major source of crop fertilizer today in most societies is still animal manure—especially of cows, but also of yaks and sheep. Manure has been valuable, too, as a source of fuel for fires in traditional societies.

驯化的大型哺乳动物还在两个方面和驯化的植物相互作用,以增加农作物的产量。首先,现代的园林工人或农民仍然根据经验知道,用动物的粪便做肥料可以提高作物的产量。即使在现代可以利用化工厂生产的合成肥料,今天大多数社会里作物肥料的主要来源仍然是动物的粪便——尤其是牛的粪便,但也有牦牛和羊的粪便。作为传统社会中的一个燃料来源,动物粪便也有其价值。

In addition, the largest domestic mammals interacted with domestic plants to increase food production by pulling plows and thereby making it possible for people to till land that had previously been uneconomical for farming. Those plow animals were the cow, horse, water buffalo, Bali cattle, and yak / cow hybrids. Here is one example of their value: the first prehistoric farmers of central Europe, the so-called Linearbandkeramik culture that arose slightly before 5000 B.C., were initially confined to soils light enough to be tilled by means of hand-held digging sticks. Only over a thousand years later, with the introduction of the ox-drawn plow, were those farmers able to extend cultivation to a much wider range of heavy soils and tough sods. Similarly, Native American farmers of the North American Great Plains grew crops in the river valleys, but farming of the tough sods on the extensive uplands had to await 19th-century Europeans and their animal-drawn plows.

此外,最大的驯化哺乳动物与驯化植物相互作用,以增加粮食产量,这表现在它们可以用来拉犁,从而使人们可以去耕种以前如用来耕种则代价太高的土地。这些用来犁地的牲口有牛、马、水牛、巴厘牛以及牦牛和牛的杂交种。这里有一个例子可以用来说明这些牲口的价值:中欧史前期最早的农民,即稍早于公元前5000年兴起的利尼尔班克拉米克文化,起初都局限于使用手持尖棍来耕作松土。仅仅过了1000年,由于采用了牛拉犁,这些农民能够把耕种扩大到范围大得多的硬实土壤和难以对付的长满了蔓草的土地上去。同样,北美大平原上的美洲土著农民在河谷种植庄稼,但在广阔高地的难以对付的长满了蔓草的土地上耕种,要等到19世纪欧洲人和他们的畜拉犁的出现。

All those are direct ways in which plant and animal domestication led to denser human populations by yielding more food than did the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. A more indirect way involved the consequences of the sedentary lifestyle enforced by food production. People of many hunter-gatherer societies move frequently in search of wild foods, but farmers must remain near their fields and orchards. The resulting fixed abode contributes to denser human populations by permitting a shortened birth interval. A hunter-gatherer mother who is shifting camp can carry only one child, along with her few possessions. She cannot afford to bear her next child until the previous toddler can walk fast enough to keep up with the tribe and not hold it back. In practice, nomadic hunter-gatherers space their children about four years apart by means of lactational amenorrhea, sexual abstinence, infanticide, and abortion. By contrast, sedentary people, unconstrained by problems of carrying young children on treks, can bear and raise as many children as they can feed. The birth interval for many farm peoples is around two years, half that of hunter-gatherers. That higher birthrate of food producers, together with their ability to feed more people per acre, lets them achieve much higher population densities than hunter-gatherers.

所有这些都是由于动植物驯化比狩猎采集的生活方式能生产出更多的食物从而导致更稠密人口的一些直接因素。一个比较间接的因素是与粮食生产所要求的定居生活方式的后果直接有关的。许多狩猎采集社会里的人经常跑来跑去寻找野生食物,但农民必须留在他们的田地和果园附近。因此而产生的固定居所由于缩短了生育间隔期而促使人口变得更稠密起来。一个经常变换营地、以狩猎采集为生的母亲只能带一个孩子和很少几件随身物品。在前一个蹒跚学步的孩子能够快步行走,赶上大伙儿而不致成为累赘之前,她是不能生第二个孩子的。事实上,到处流浪的以狩猎采集为生的人通过哺乳期无月经、禁欲、杀婴和堕胎等办法,把孩子出生的间隔安排为大约每4年一个。相比之下,定居的部族由于没有在迁移途中携带小孩这种问题的限制,他们可以多生多养,只要养得活就行。许多农业部族的生育间隔期是两年左右,为狩猎采集部族的一半。粮食生产者的这种较高的出生率,加上他们按每英亩计算养活更多的人的能力,使他们达到了比狩猎采集部族更大的人口密度。

A separate consequence of a settled existence is that it permits one to store food surpluses, since storage would be pointless if one didn't remain nearby to guard the stored food. While some nomadic hunter-gatherers may occasionally bag more food than they can consume in a few days, such a bonanza is of little use to them because they cannot protect it. But stored food is essential for feeding non-food-producing specialists, and certainly for supporting whole towns of them. Hence nomadic hunter-gatherer societies have few or no such full-time specialists, who instead first appear in sedentary societies.

定居生活的另一个结果是人们可以把多余的粮食贮藏起来,因为如果人们不能留在附近看管贮藏的粮食,那么贮藏就是毫无意义的。虽然有些到处流浪的狩猎采集部族可能偶尔也把几天吃不完的食品收藏起来,但这种富源对他们几乎毫无用处,因为他们不能保护它。但贮藏的粮食对于养活不生产粮食的专门人材是必不可少的,而对于养活全村社的人肯定是必不可少的。因此,到处流浪的狩猎采集社会几乎没有或完全没有这类专职的专门人材,这种人材首先出现在定居社会中。

Two types of such specialists are kings and bureaucrats. Hunter-gatherer societies tend to be relatively egalitarian, to lack full-time bureaucrats and hereditary chiefs, and to have small-scale political organization at the level of the band or tribe. That's because all able-bodied hunter-gatherers are obliged to devote much of their time to acquiring food. In contrast, once food can be stockpiled, a political elite can gain control of food produced by others, assert the right of taxation, escape the need to feed itself, and engage full-time in political activities. Hence moderate-sized agricultural societies are often organized in chiefdoms, and kingdoms are confined to large agricultural societies. Those complex political units are much better able to mount a sustained war of conquest than is an egalitarian band of hunters. Some hunter-gatherers in especially rich environments, such as the Pacific Northwest coast of North America and the coast of Ecuador, also developed sedentary societies, food storage, and nascent chiefdoms, but they did not go farther on the road to kingdoms.

这种专门人材有两类:国王和官员。狩猎采集社会往往比较平等,它们没有专职的官员和世袭的首领,只有在族群和部落层次上的小规模的行政组织。这是因为所有的身强力壮的从事狩猎采集的人不得不把他们很大一部分时间专门用来获取食物。而一旦有了粮食储备,行政上层人物就可以控制别人生产的粮食,维护征税的权利,无需去养活自己,而以全部时间从事行政活动。因此,中等规模的农业社会通常按酋长辖地来组织,而王国只限于规模很大的农业社会。这些复杂的行政单位比平等主义的猎人群体能更好地发动持久的征服战争。有些狩猎采集部族由于生活在特别富足的环境里,如北美洲太平洋西北海岸和厄瓜多尔海岸,也逐渐形成了定居社会,有了粮食储备和新生的酋长辖地,但他们没有在通往王国的道路上更进一步。

A stored food surplus built up by taxation can support other full-time specialists besides kings and bureaucrats. Of most direct relevance to wars of conquest, it can be used to feed professional soldiers. That was the decisive factor in the British Empire's eventual defeat of New Zealand's well-armed indigenous Maori population. While the Maori achieved some stunning temporary victories, they could not maintain an army constantly in the field and were in the end worn down by 18,000 full-time British troops. Stored food can also feed priests, who provide religious justification for wars of conquest; artisans such as metalworkers, who develop swords, guns, and other technologies; and scribes, who preserve far more information than can be remembered accurately.

通过税收建立剩余粮食储备,除了养活国王和官员外,还能养活其他专职的专门人材。与征服战争关系最直接的是,剩余粮食储备可以用来养活职业军人。这是不列颠帝国最终打败新西兰武装精良的本土毛利人的决定性因素。虽然毛利人取得了几次惊人的暂时胜利,但他们不能在战场上保持一支常备军,所以到头来还是被18000人的英国专职军队拖垮了。粮食储备还可以养活为征服战争提供宗教理由的神职人员,养活像制造刀剑、枪炮和发展其他技术的金属加工工人之类的手艺人,以及养活能够保存信息的抄写员,因为他们所记录的信息比人们能够准确记住的信息要多得多。

So far, I've emphasized direct and indirect values of crops and livestock as food. However, they have other uses, such as keeping us warm and providing us with valuable materials. Crops and livestock yield natural fibers for making clothing, blankets, nets, and rope. Most of the major centers of plant domestication evolved not only food crops but also fiber crops—notably cotton, flax (the source of linen), and hemp. Several domestic animals yielded animal fibers—especially wool from sheep, goats, llamas, and alpacas, and silk from silkworms. Bones of domestic animals were important raw materials for artifacts of Neolithic peoples before the development of metallurgy. Cow hides were used to make leather. One of the earliest cultivated plants in many parts of the Americas was grown for nonfood purposes: the bottle gourd, used as a container.

至此,我已着重指出了作为粮食的农作物和家畜的直接和间接的价值。然而,它们还有其他用途,例如帮我们保暖和向我们提供有价值的材料。农作物和家畜生产出的天然纤维,可以用来做衣服、毯子、网和绳子。大多数重要的植物驯化中心不但培育粮食作物,也培育纤维作物——主要有棉花、亚麻(亚麻布的原料)和大麻。有几种驯化动物则出产动物纤维——特别是绵羊、山羊、美洲驼和羊驼的毛以及蚕丝。驯化动物的骨头是冶金术发明前新石器时代各部族用作人工制品的重要原料。牛皮被用来制革。在美洲许多地方栽培最早的植物之一是为非食用目的而种植的,这就是用作容器的葫芦。

Big domestic mammals further revolutionized human society by becoming our main means of land transport until the development of railroads in the 19th century. Before animal domestication, the sole means of transporting goods and people by land was on the backs of humans. Large mammals changed that: for the first time in human history, it became possible to move heavy goods in large quantities, as well as people, rapidly overland for long distances. The domestic animals that were ridden were the horse, donkey, yak, reindeer, and Arabian and Bactrian camels. Animals of those same five species, as well as the llama, were used to bear packs. Cows and horses were hitched to wagons, while reindeer and dogs pulled sleds in the Arctic. The horse became the chief means of long-distance transport over most of Eurasia. The three domestic camel species (Arabian camel, Bactrian camel, and llama) played a similar role in areas of North Africa and Arabia, Central Asia, and the Andes, respectively.

驯化的大型哺乳动物在19世纪铁路发展起来之前成为我们主要的陆路运输手段,从而进一步使人类社会发生了革命性的剧变。在动物驯化之前,由陆路运输货物和人的唯一手段就是用人来背。大型哺乳动物改变了这种情况:在人类历史上第一次有可能迅速地不但把人而且也把大量沉重的货物从陆路运到很远的地方去。供人骑乘的驯化动物有马、驴、牦牛、驯鹿、阿拉伯单峰驼和中亚双峰驼。这5种动物和羊驼一样,都被用来背负行囊包裹。牛和马被套上大车,而驯鹿和狗则在北极地区拉雪橇。在欧亚大陆大部分地区,马成了长距离运输的主要手段。3种驯化骆驼(阿拉伯单峰驼、中亚双峰驼和羊驼)分别在北非地区和阿拉伯半岛、中亚和安第斯山脉地区起着类似的作用。

The most direct contribution of plant and animal domestication to wars of conquest was from Eurasia's horses, whose military role made them the jeeps and Sherman tanks of ancient warfare on that continent. As I mentioned in Chapter 3, they enabled Cortés and Pizarro, leading only small bands of adventurers, to overthrow the Aztec and Inca Empires. Even much earlier (around 4000 B.C.), at a time when horses were still ridden bareback, they may have been the essential military ingredient behind the westward expansion of speakers of Indo-European languages from the Ukraine. Those languages eventually replaced all earlier western European languages except Basque. When horses later were yoked to wagons and other vehicles, horse-drawn battle chariots (invented around 1800 B.C.) proceeded to revolutionize warfare in the Near East, the Mediterranean region, and China. For example, in 1674 B.C., horses even enabled a foreign people, the Hyksos, to conquer then horseless Egypt and to establish themselves temporarily as pharaohs.

动植物驯化对征服战争的最直接的贡献是由欧亚大陆的马作出的,它们在军事上的作用,使它成了那个大陆上古代战争中的吉普车和谢尔曼坦克。我在第三章中提到,马使得仅仅率领一小群冒险家的科尔特斯和皮萨罗能够推翻阿兹特克帝国和印加帝国。甚至在早得多的时候(公元前4000年左右),尽管那时人们还仍然骑在光马背上,但马可能已成为促使操印欧语的人从乌克兰向西扩张的必不可少的军事要素。这些语言最终取代了除巴斯克语[1]外的所有早期的欧洲语言。当马在后来被套上马车和其他车辆时,马拉战车(公元前1800年左右发明)开始在近东、地中海地区和中国使战争发生了革命性的剧变。例如,在公元前1674年,马甚至使外来的希克索斯民族[2]得以征服当时没有马的埃及并短暂地自立为法老。

Still later, after the invention of saddles and stirrups, horses allowed the Huns and successive waves of other peoples from the Asian steppes to terrorize the Roman Empire and its successor states, culminating in the Mongol conquests of much of Asia and Russia in the 13th and 14th centuries A.D. Only with the introduction of trucks and tanks in World War I did horses finally become supplanted as the main assault vehicle and means of fast transport in war. Arabian and Bactrian camels played a similar military role within their geographic range. In all these examples, peoples with domestic horses (or camels), or with improved means of using them, enjoyed an enormous military advantage over those without them.

再往后,在马鞍和马镫发明后,马使来自亚洲大草原的匈奴人和一波接一波的其他民族对罗马帝国和后继国家造成了威胁,最后以蒙古人于公元13世纪和14世纪征服亚洲和俄罗斯的许多地方而达到高潮。只是由于在第一次世界大战中采用了卡车和坦克,马的作用才最后被取代,而不再是战争中主要的突击手段和快速运输的工具。阿拉伯骆驼和中亚骆驼也在各自的地理范围内起到了类似的军事作用。在所有这些例子中,驯养马匹(或骆驼)或改进对其利用的民族,在军事上拥有了对没有这些牲口的民族的巨大优势。

Of equal importance in wars of conquest were the germs that evolved in human societies with domestic animals. Infectious diseases like smallpox, measles, and flu arose as specialized germs of humans, derived by mutations of very similar ancestral germs that had infected animals (Chapter 11). The humans who domesticated animals were the first to fall victim to the newly evolved germs, but those humans then evolved substantial resistance to the new diseases. When such partly immune people came into contact with others who had had no previous exposure to the germs, epidemics resulted in which up to 99 percent of the previously unexposed population was killed. Germs thus acquired ultimately from domestic animals played decisive roles in the European conquests of Native Americans, Australians, South Africans, and Pacific islanders.

在征服战争中同样重要的是在驯养动物的社会中演化的病菌。像天花、麻疹和流行性感冒这类传染病作为人类的专化病菌而出现了,它们原是动物所感染的十分类似的祖代病菌由于突变而衍生出来的(第十一章)。驯养动物的人成了这些新演化出来的病菌的第一个受害者,而这些人接着又逐步形成了对这些新的疾病的强大的抵抗力。当这些有部分免疫力的人与以前从来没有接触过这种病菌的人接触时,流行病于是产生了,使99%的以前没有接触过这种病菌的人因之而丧命。从驯养的动物那里通过这一途径而最后获得的病菌,在欧洲人对美洲、澳大利亚、南非和太平洋诸岛的土著的征服中起了决定性的作用。

In short, plant and animal domestication meant much more food and hence much denser human populations. The resulting food surpluses, and (in some areas) the animal-based means of transporting those surpluses, were a prerequisite for the development of settled, politically centralized, socially stratified, economically complex, technologically innovative societies. Hence the availability of domestic plants and animals ultimately explains why empires, literacy, and steel weapons developed earliest in Eurasia and later, or not at all, on other continents. The military uses of horses and camels, and the killing power of animal-derived germs, complete the list of major links between food production and conquest that we shall be exploring.

总之,动植物的驯化意味着人类的粮食越来越多,因而也就意味着人口越来越稠密。因此而带来的粮食剩余和(在某些地区)利用畜力运输剩余粮食,成了定居的、行政上集中统一的、社会等级分明的、经济上复杂的、技术上富有革新精神的社会的发展的先决条件。因此,能否利用驯化的动植物,最终说明了为什么帝国、知书识字和钢铁武器在欧亚大陆最早发展起来,而在其他大陆则发展较晚,或根本没有发展起来。在军事上使用马和骆驼以及来自动物的病菌的致命力量,最后就把粮食生产和征服之间的许多重要环节连接了起来,这我将在下文予以考察。

注释:

1 . 巴斯克语:欧洲比利牛斯山西部地区古老居民巴斯克人的语言。——译者

2 . 希克索斯民族:来自亚洲的入侵者,从公元前18世纪末至公元前16世纪初统治埃及,其所建立之希克索斯王朝亦称“牧人王朝”。——译者