CHAPTER 5

第五章

HISTORY'S HAVES AND HAVE-NOTS

历史上的穷与富

MUCH OF HUMAN HISTORY HAS CONSISTED OF UNEQUAL conflicts between the haves and the have-nots: between peoples with farmer power and those without it, or between those who acquired it at different times. It should come as no surprise that food production never arose in large areas of the globe, for ecological reasons that still make it difficult or impossible there today. For instance, neither farming nor herding developed in prehistoric times in North America's Arctic, while the sole element of food production to arise in Eurasia's Arctic was reindeer herding. Nor could food production spring up spontaneously in deserts remote from sources of water for irrigation, such as central Australia and parts of the western United States.

很大一部分人类历史充满了穷富之间不平等的斗争:具有农民力量的民族与不具有农民力量的民族之间的斗争,或不同时期获得农民力量的民族之间的斗争。粮食生产在地球上的广大地区过去没有出现过,这并不令人奇怪,由于生态原因,粮食生产在这些地区现在仍然难以出现或不可能出现。例如,在史前期的北美洲北极地区,无论农业或畜牧业都没有出现过,而在欧亚大陆北极地区出现的唯一粮食生产要素是放牧驯鹿。在远离灌溉水源的沙漠地区也不可能自发地出现粮食生产,如澳大利亚中部和美国西部的一些地方。

Instead, what cries out for explanation is the failure of food production to appear, until modern times, in some ecologically very suitable areas that are among the world's richest centers of agriculture and herding today. Foremost among these puzzling areas, where indigenous peoples were still hunter-gatherers when European colonists arrived, were California and the other Pacific states of the United States, the Argentine pampas, southwestern and southeastern Australia, and much of the Cape region of South Africa. Had we surveyed the world in 4000 B.C., thousands of years after the rise of food production in its oldest sites of origin, we would have been surprised too at several other modern breadbaskets that were still then without it—including all the rest of the United States, England and much of France, Indonesia, and all of subequatorial Africa. When we trace food production back to its beginnings, the earliest sites provide another surprise. Far from being modern breadbaskets, they include areas ranking today as somewhat dry or ecologically degraded: Iraq and Iran, Mexico, the Andes, parts of China, and Africa's Sahel zone. Why did food production develop first in these seemingly rather marginal lands, and only later in today's most fertile farmlands and pastures?

迫切需要说明的,反倒是何以在某些生态条件十分适宜的地区在现代以前一直未能出现粮食生产,而在今天却成了世界上一些最富足的农牧中心。最为令人费解的一些地区,是加利福尼亚和美国太平洋沿岸其他一些州、阿根廷的无树大草原、澳大利亚西南部和东南部以及南非好望角地区的很大一部分。这些地区的土著族群在欧洲移民来到时还仍然过着狩猎采集生活。如果我们考察一下公元前4000年的世界,即粮食生产在其最早发源地出现后几千年的世界,我们可能也会对其他几个现代粮仓当时竟未出现粮食生产而感到惊异。这些盛产谷物的地区包括:美国其余所有的地区、英国、法国很大一部分地区、印度尼西亚以及非洲赤道以南的整个地区。如果我们对粮食生产追本溯源,它的最早发源地会再次使我们感到惊异。这些地方已完全不是现代粮仓,它们包括一些在今天被列为有点干旱或生态退化的地区:伊拉克和伊朗、墨西哥、安第斯山脉、中国的部分地区以及非洲的萨赫勒地带[1]。为什么粮食生产首先在看似相当贫瘠的土地上形成,只是到后来才在今天最肥沃的农田和牧场发展起来?

Geographic differences in the means by which food production arose are also puzzling. In a few places it developed independently, as a result of local people domesticating local plants and animals. In most other places it was instead imported, in the form of crops and livestock that had been domesticated elsewhere. Since those areas of nonindependent origins were suitable for prehistoric food production as soon as domesticates had arrived, why did the peoples of those areas not become farmers and herders without outside assistance, by domesticating local plants and animals?

在粮食生产赖以出现的方式方面的地理差异也同样令人费解。在有些地方,它是独立发展起来的,这是当地人驯化当地动植物的结果。而在其他大多数地方,则是把别的地方已经驯化的作物和牲口加以引进。既然这些原来不是独立发展粮食生产的地区在引进驯化动植物后立刻变得适宜于史前的粮食生产,那么这些地区的各个族群为什么在没有外来帮助的情况下,通过驯化当地的动植物而成为农民和牧人呢?

Among those regions where food production did spring up independently, why did the times at which it appeared vary so greatly—for example, thousands of years earlier in eastern Asia than in the eastern United States and never in eastern Australia? Among those regions into which it was imported in the prehistoric era, why did the date of arrival also vary so greatly—for example, thousands of years earlier in southwestern Europe than in the southwestern United States? Again among those regions where it was imported, why in some areas (such as the southwestern United States) did local hunter-gatherers themselves adopt crops and livestock from neighbors and survive as farmers, while in other areas (such as Indonesia and much of subequatorial Africa) the importation of food production involved a cataclysmic replacement of the region's original hunter-gatherers by invading food producers? All these questions involve developments that determined which peoples became history's have-nots, and which became its haves.

在的确独立出现粮食生产的这些地区中,为什么出现的时间差别如此之大——例如,在东亚要比在美国东部早几千年,而在澳大利亚东部却又从来没有出现过?在史前时代引进粮食生产的这些地区中,为什么引进的时间差别也如此之大——例如,在欧洲西南部要比在美国西南部早几千年?另外,在引进粮食生产的这些地区中,为什么在有些地区(如美国西南部)当地的狩猎采集族群采纳了邻近族群的作物和牲口而最后成为农民,而在另一些地区(如印度尼西亚和非洲赤道以南的许多地方)引进粮食生产却引起了一场灾难,使外来的粮食生产者取代了该地区原来的狩猎采集族群呢?所有这些问题都涉及不同的发展阶段,而正是这些不同的发展阶段决定了哪些民族成了历史上的贫穷民族,哪些民族成了历史上的富有民族。

BEFORE WE CAN hope to answer these questions, we need to figure out how to identify areas where food production originated, when it arose there, and where and when a given crop or animal was first domesticated. The most unequivocal evidence comes from identification of plant and animal remains at archaeological sites. Most domesticated plant and animal species differ morphologically from their wild ancestors: for example, in the smaller size of domestic cattle and sheep, the larger size of domestic chickens and apples, the thinner and smoother seed coats of domestic peas, and the corkscrew-twisted rather than scimitar-shaped horns of domestic goats. Hence remains of domesticated plants and animals at a dated archaeological site can be recognized and provide strong evidence of food production at that place and time, whereas finding the remains only of wild species at a site fails to provide evidence of food production and is compatible with hunting-gathering. Naturally, food producers, especially early ones, continued to gather some wild plants and hunt wild animals, so the food remains at their sites often include wild species as well as domesticated ones.

在我们能够指望回答这些问题之前,我们需要弄清楚怎样去确定粮食生产的发源地及其出现的时间,以及某一特定作物或动物最早得到驯化的地点和时间。最明确的证据来自对一些考古遗址中出土的动植物残骸所作的鉴定。大多数驯化的动植物物种在形态上同它们的野生祖先是不同的:例如,驯化的牛和羊形体较小,驯化的鸡和苹果形体较大,驯化的豌豆种皮较薄也较光滑,驯化的山羊角长成螺旋形而不是短弯刀状。因此,如果能在一处有年代可考的考古遗址认出驯化动植物的残骸,那就是有了强有力的证据,说明彼时彼地已有了粮食生产,而如果在某个遗址仅仅发现了野生物种,那就不能证明已有了粮食生产,而只能证明与狩猎采集生活相吻合。当然,粮食生产者,尤其是初期的粮食生产者,在继续采集某些野生植物和猎捕野兽,这样,他们遗址中的残余食物常常不但包括驯化的物种,而且也包括野生的物种。

Archaeologists date food production by radiocarbon dating of carbon-containing materials at the site. This method is based on the slow decay of radioactive carbon 14, a very minor component of carbon, the ubiquitous building block of life, into the nonradioactive isotope nitrogen 14. Carbon 14 is continually being generated in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. Plants take up atmospheric carbon, which has a known and approximately constant ratio of carbon 14 to the prevalent isotope carbon 12 (a ratio of about one to a million). That plant carbon goes on to form the body of the herbivorous animals that eat the plants, and of the carnivorous animals that eat those herbivorous animals. Once the plant or animal dies, though, half of its carbon 14 content decays into carbon 12 every 5,700 years, until after about 40,000 years the carbon 14 content is very low and difficult to measure or to distinguish from contamination with small amounts of modern materials containing carbon 14. Hence the age of material from an archaeological site can be calculated from the material's carbon 14 / carbon 12 ratio.

考古学家们用碳-14年代测定法来测定遗址中的含碳物质,从而确定粮食生产的年代。这种测定法所依据的原理是这样的:碳是生命的无所不在的基础材料,它的成分中含有很少量的放射性碳-14,而碳-14会衰变为非放射性同位素氮-14。宇宙射线不断地在大气中生成碳-14。植物吸收大气中的碳,其中碳-14和普遍存在的同位素碳-12保持着一种已知的几乎不变的比例(约1与100万之比)。植物中的碳接下去构成了吃这些植物的食草动物的躯体,也构成了吃这些食草动物的食肉动物的躯体。不过,这些植物或动物一旦死去,它们体内碳-14含量的一半每隔5700年衰变为碳-12,直到大约4万年后,碳-14含量变得很低而很难测出,也很难把它同受到少量的含有碳-14的现代材料的污染区别开来。因此,从考古遗址出土的材料的年代可以根据该材料内的碳-14与碳-12的比例计算出来。

Radiocarbon is plagued by numerous technical problems, of which two deserve mention here. One is that radiocarbon dating until the 1980s required relatively large amounts of carbon (a few grams), much more than the amount in small seeds or bones. Hence scientists instead often had to resort to dating material recovered nearby at the same site and believed to be “associated with” the food remains—that is, to have been deposited simultaneously by the people who left the food. A typical choice of “associated” material is charcoal from fires.

放射性碳受到许多技术问题的困扰,其中两个问题值得在这里提一提。一个问题是:碳-14年代测定法在20世纪80年代前需要比较多的碳(几克),比小小的种子或骨头里碳的含量多得多。因此,科学家们常常不得不依靠测定在同一遗址附近找到的材料的年代,而这个材料被认为是与残存的食物“有联系”的——就是说,是被留下食物的人同时弃置的。通常选择的“有联系”的材料是烧过的木炭。

But archaeological sites are not always neatly sealed time capsules of materials all deposited on the same day. Materials deposited at different times can get mixed together, as worms and rodents and other agents churn up the ground. Charcoal residues from a fire can thereby end up close to the remains of a plant or animal that died and was eaten thousands of years earlier or later. Increasingly today, archaeologists are circumventing this problem by a new technique termed accelerator mass spectrometry, which permits radiocarbon dating of tiny samples and thus lets one directly date a single small seed, small bone, or other food residue. In some cases big differences have been found between recent radiocarbon dates based on the direct new methods (which have their own problems) and those based on the indirect older ones. Among the resulting controversies remaining unresolved, perhaps the most important for the purposes of this book concerns the date when food production originated in the Americas: indirect methods of the 1960s and 1970s yielded dates as early as 7000 B.C., but more recent direct dating has been yielding dates no earlier than 3500 B.C.

但是,考古遗址并不总是把所有同日弃置的材料巧妙密封起来的时间容器。在不同时间弃置的材料可能会混杂在一起,因为蠕虫、啮齿目动物和其他作用力把地层给搅乱了。燃烧过的木炭碎屑最后可能因此而靠近了某个死去的并在几千年中或早或晚被吃掉的植物或动物。今天,考古学家们越来越多地用一种叫做加速质谱分析法的新技术来解决这个问题,这种新技术可以使碳-14年代测定法测得极小的样本的年代,从而使人们可以直接地测得一粒小小的种子、一块小小的骨片或其他食物残渣的年代。近年来用碳-14年代测定法测得的年代,有的是根据这种新的直接方法(它们也有其自身的问题),有的是根据旧的间接方法。但在有些情况下,人们发现用这两种方法测得的年代存在着巨大的差异。在由此而产生的仍未解决的争论中,就本书的论题而言,最重要的也许是有关粮食生产在美洲出现的年代问题:20世纪60年代和70年代的间接方法测得的年代是远在公元前7万年,而较近的直接方法测得的年代则不早于公元前3500年。

A second problem in radiocarbon dating is that the carbon 14/carbon 12 ratio of the atmosphere is in fact not rigidly constant but fluctuates slightly with time, so calculations of radiocarbon dates based on the assumption of a constant ratio are subject to small systematic errors. The magnitude of this error for each past date can in principle be determined with the help of long-lived trees laying down annual growth rings, since the rings can be counted up to obtain an absolute calendar date in the past for each ring, and a carbon sample of wood dated in this manner can then be analyzed for its carbon 14 / carbon 12 ratio. In this way, measured radiocarbon dates can be “calibrated” to take account of fluctuations in the atmospheric carbon ratio. The effect of this correction is that, for materials with apparent (that is, uncalibrated) dates between about 1000 and 6000 B.C., the true (calibrated) date is between a few centuries and a thousand years earlier. Somewhat older samples have more recently begun to be calibrated by an alternative method based on another radioactive decay process and yielding the conclusion that samples apparently dating to about 9000 B.C. actually date to around 11,000 B.C.

碳-14年代测定法的第二个问题是:大气中碳-14与碳-12的比例事实上并不是严格不变的,而是随着时间上下波动的,因此,从某种不变的比例这种假定出发去计算碳-14年代测定法测得的年代经常会产生一些小小的错误。确定关于过去每个年代错误的程度,原则上可以借助古老树木记录下的年轮,因为只要数一数这些年轮,就可得到每个年轮在过去的绝对日历年代,然后再对用这种方法测定年代的木炭样本加以分析,来确定其中碳-14与碳-12的比例。这样,就可以对用碳-14年代测定法实测到的年代加以校正,来估计大气中碳比例的波动情况。这样校正的结果是:对从表面上看(即未经校正的)其年代介于公元前约1000年至6000年之间的一些材料来说,精确的(经过校正的)年代要早几百年或1000年。近来又有人用一种交替法开始对一些年代稍早的样本进行校正,这种方法所依据的是另一种放射性衰变法,它所得出的结论是,表面上看年代约为公元前9000年的样本的实际年代是公元前11000年左右。

Archaeologists often distinguish calibrated from uncalibrated dates by writing the former in upper-case letters and the latter in lower-case letters (for example, 3000 B.C. vs. 3000 B.C., respectively). However, the archaeological literature can be confusing in this respect, because many books and papers report uncalibrated dates as B.C. and fail to mention that they are actually uncalibrated. The dates that I report in this book for events within the last 15,000 years are calibrated dates. That accounts for some of the discrepancies that readers may note between this book's dates and those quoted in some standard reference books on early food production.

考古学家们常常把经过校正的和未经过校正的年代加以区分,其方法就是对前者用大写英文字母来写,对后者用小写英文字母来写(例如,分别为3000B.C.和3000b.c.)。然而,考古文献在这方面可能很混乱,因为许多书和论文在报告未经校正的年代时都写作B.C.,而未能提到这些年代实际上是未经校正的。我在本书中所报道的关于过去15000年中一些事件的年代都是经过校正的年代。这就是为什么读者会注意到关于早期粮食生产问题本书中的一些年代与从某些标准参考书引用的年代存在着差异的原因。

Once one has recognized and dated ancient remains of domestic plants or animals, how does one decide whether the plant or animal was actually domesticated in the vicinity of that site itself, rather than domesticated elsewhere and then spread to the site? One method is to examine a map of the geographic distribution of the crop's or animal's wild ancestor, and to reason that domestication must have taken place in the area where the wild ancestor occurs. For example, chickpeas are widely grown by traditional farmers from the Mediterranean and Ethiopia east to India, with the latter country accounting for 80 percent of the world's chickpea production today. One might therefore have been deceived into supposing that chickpeas were domesticated in India. But it turns out that ancestral wild chickpeas occur only in southeastern Turkey. The interpretation that chickpeas were actually domesticated there is supported by the fact that the oldest finds of possibly domesticated chickpeas in Neolithic archaeological sites come from southeastern Turkey and nearby northern Syria that date to around 8000 B.C.; not until over 5,000 years later does archaeological evidence of chickpeas appear on the Indian subcontinent.

一旦人们辨认出驯化动植物的古代遗存并确定其年代,那么人们怎样来确定是否这个植物或动物实际上就是在这遗址附近驯化的,而不是在别处驯化,后来才传到这个遗址来的?一个方法就是研究一下这个作物或动物的野生祖先的地理分布图,并推断出野生祖先出现的地方必定就是发生过驯化的地方。例如,从地中海和埃塞俄比亚往东到印度,传统的农民普遍种植鹰嘴豆,今天世界上鹰嘴豆的80%都是印度生产的。因此,人们可能会误以为鹰嘴豆是在印度驯化的。但结果表明,鹰嘴豆的野生祖先只出现在土耳其的东南部。鹰嘴豆实际上是在那里驯化的,这个解释得到了这样一个事实的证明,即在新石器遗址中有关可能是驯化的鹰嘴豆的最古老的发现来自土耳其东南部和叙利亚北部邻近地区,其年代为公元前8000年左右;直到5000多年后,关于鹰嘴豆的考古证据才在印度次大陆出现。

A second method for identifying a crop's or animal's site of domestication is to plot on a map the dates of the domesticated form's first appearance at each locality. The site where it appeared earliest may be its site of initial domestication—especially if the wild ancestor also occurred there, and if the dates of first appearance at other sites become progressively later with increasing distance from the putative site of initial domestication, suggesting spread to those other sites. For instance, the earliest known cultivated emmer wheat comes from the Fertile Crescent around 8500 B.C. Soon thereafter, the crop appears progressively farther west, reaching Greece around 6500 B.C. and Germany around 5000 B.C. Those dates suggest domestication of emmer wheat in the Fertile Crescent, a conclusion supported by the fact that ancestral wild emmer wheat is confined to the area extending from Israel to western Iran and Turkey.

确定某个作物或动物的驯化地点的第二个方法,是在地图上标出每个地区驯化物种首次出现的年代。出现年代最早的地点也许就是驯化最早的地点——而如果野生物种的祖先也在那里出现,如果它们在其他地点首次出现的年代随着与推定的最早驯化地点距离的增加而渐次提早,从而表明驯化物种在向其他那些地点传播,情况就尤其如此。例如,已知最早的人工栽培的二粒小麦在公元前8500年左右出现在新月沃地。其后不久,这个作物逐步向西传播,在公元前6500年左右到达希腊,在公元前5000年左右到达德国。这些年代表明二粒小麦是在新月沃地驯化的,这一结论可以用以下事实来证明:二粒小麦的野生祖先的分布只限于从以色列到伊朗西部和土耳其这一地区。

However, as we shall see, complications arise in many cases where the same plant or animal was domesticated independently at several different sites. Such cases can often be detected by analyzing the resulting morphological, genetic, or chromosomal differences between specimens of the same crop or domestic animal in different areas. For instance, India's zebu breeds of domestic cattle possess humps lacking in western Eurasian cattle breeds, and genetic analyses show that the ancestors of modern Indian and western Eurasian cattle breeds diverged from each other hundreds of thousands of years ago, long before any animals were domesticated anywhere. That is, cattle were domesticated independently in India and western Eurasia, within the last 10,000 years, starting with wild Indian and western Eurasian cattle subspecies that had diverged hundreds of thousands of years earlier.

然而,在许多情况下,如果同样的植物或动物是在不同的地点独立驯化的,那么就会出现一些复杂的情况。只要分析一下由此产生的不同地区的相同作物或动物标本在形态、遗传或染色体方面的差异,就常常可以发现这些情况。例如,印度驯化牛中的瘤牛品种具有欧亚大陆西部牛的品种所没有的肉峰。遗传分析表明,现代印度牛的品种和欧亚大陆西部牛的品种在几十万年前就已分化了,比任何地方任何动物驯化的时间都早得多。就是说,在过去1万年中,牛就已在印度和欧亚大陆西部独立地驯化了,而它们原来都是在几十万年以前就已分化的印度和欧亚大陆西部野牛的亚种。

LET'S NOW RETURN to our earlier questions about the rise of food production. Where, when, and how did food production develop in different parts of the globe?

现在,让我们再回到我们原先的关于粮食生产的出现这个问题上来。在世界上的不同地区,粮食生产是在何处、何时和如何发展起来的呢?

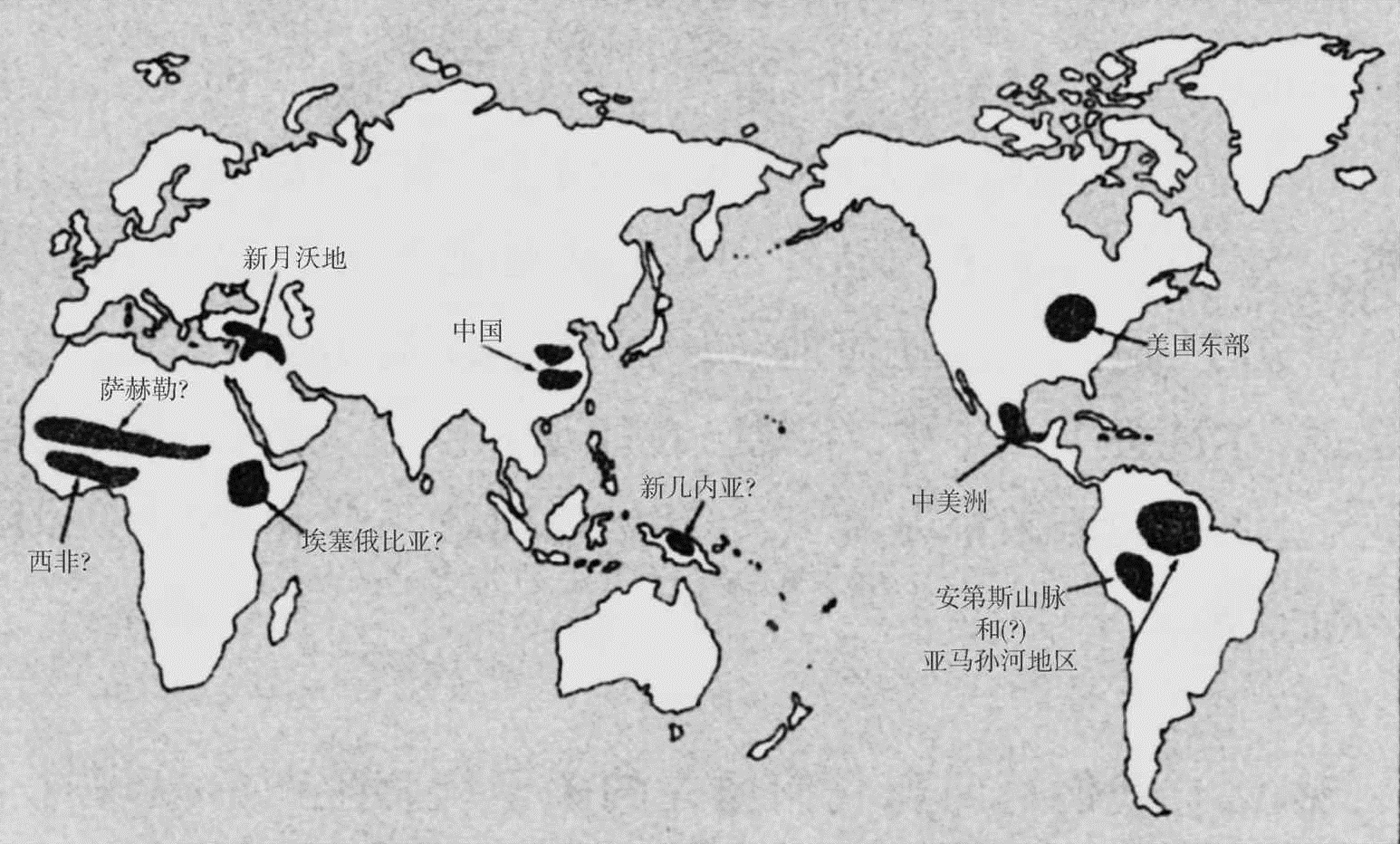

At one extreme are areas in which food production arose altogether independently, with the domestication of many indigenous crops (and, in some cases, animals) before the arrival of any crops or animals from other areas. There are only five such areas for which the evidence is at present detailed and compelling: Southwest Asia, also known as the Near East or Fertile Crescent; China; Mesoamerica (the term applied to central and southern Mexico and adjacent areas of Central America); the Andes of South America, and possibly the adjacent Amazon Basin as well; and the eastern United States (Figure 5.1). Some or all of these centers may actually comprise several nearby centers where food production arose more or less independently, such as North China's Yellow River valley and South China's Yangtze River valley.

一个极端情况是:有些地区的粮食生产完全是独立出现的,在其他地区的任何作物或动物来到之前,许多本土作物(在有些情况下还有动物)就已驯化了。目前能够举出详细而又令人信服的证据的这样的地区只有5个:西南亚,亦称近东或新月沃地;中国;中美洲(该词用来指墨西哥的中部和南部以及中美洲的毗连地区);南美洲的安第斯山脉地区,可能还有亚马孙河流域的毗连地区;以及美国东部(图5.1)。在这些粮食生产中心中,有些中心或所有中心可能实际上包含了附近的几个或多或少独立出现粮食生产的中心,如中国北方的黄河流域和中国南部的长江流域。

Figure 5.1. Centers of origin of food production. A question mark indicates some uncertainty whether the rise of food production at that center was really uninfluenced by the spread of food production from other centers, or (in the case of New Guinea) what the earliest crops were.

图5.1粮食生产发源中心。问号表示不十分肯定粮食生产在该中心出现是否确实不是由于受到其他中心粮食生产传播的影响,或(就新几内亚来说)最早的作物是什么。

In addition to these five areas where food production definitely arose de novo, four others—Africa's Sahel zone, tropical West Africa, Ethiopia, and New Guinea—are candidates for that distinction. However, there is some uncertainty in each case. Although indigenous wild plants were undoubtedly domesticated in Africa's Sahel zone just south of the Sahara, cattle herding may have preceded agriculture there, and it is not yet certain whether those were independently domesticated Sahel cattle or, instead, domestic cattle of Fertile Crescent origin whose arrival triggered local plant domestication. It remains similarly uncertain whether the arrival of those Sahel crops then triggered the undoubted local domestication of indigenous wild plants in tropical West Africa, and whether the arrival of Southwest Asian crops is what triggered the local domestication of indigenous wild plants in Ethiopia. As for New Guinea, archaeological studies there have provided evidence of early agriculture well before food production in any adjacent areas, but the crops grown have not been definitely identified.

除了这5个确然无疑出现粮食生产的地区外,另外还有4个地区——非洲的萨赫勒地带、热带西非、埃塞俄比亚和新几内亚——是争取这一荣誉称号的候补地区。然而,每一个地区都有某种不确定之处。虽然在非洲撒哈拉沙漠南沿的萨赫勒地带毫无疑问已有本地野生植物的驯化,但那里牛的放牧可能在农业出现前就已开始了,目前尚不能肯定的是:这些牛是独立驯化的萨赫勒牛,或者本来就是新月沃地饲养的牛,它们的引进引发了当地植物的驯化。同样仍然不能肯定的是,这些萨赫勒作物的引进是否接着又在热带西非引发了当地人对本地野生植物的无庸置疑的驯化,而西南亚作物的引进是否就是在埃塞俄比亚引发当地人驯化本地野生植物的原因。至于新几内亚,那里的考古研究提供的证据表明,在任何毗连地区出现粮食生产之前很久,那里就已有了早期的农业,但那里种植什么作物却一直没有得到明确的认定。

Table 5.1 summarizes, for these and other areas of local domestication, some of the best-known crops and animals and the earliest known dates of domestication. Among these nine candidate areas for the independent evolution of food production, Southwest Asia has the earliest definite dates for both plant domestication (around 8500 B.C.) and animal domestication (around 8000 B.C.); it also has by far the largest number of accurate radiocarbon dates for early food production. Dates for China are nearly as early, while dates for the eastern United States are clearly about 6,000 years later. For the other six candidate areas, the earliest well-established dates do not rival those for Southwest Asia, but too few early sites have been securely dated in those six other areas for us to be certain that they really lagged behind Southwest Asia and (if so) by how much.

表5.1为在本地驯化的那些地区和其他地区扼要地列出了一些最著名的作物或动物以及已知的最早的驯化年代。在9个独立发展粮食生产的候补地区中,西南亚是植物驯化(公元前8500年左右)和动物驯化(公元前8000年左右)有最早的明确年代的地区;同时对于早期的粮食生产来说,它显然也是具有最多的用碳-14测定的准确年代的地区。中国发展粮食生产的年代几乎同西南亚一样早,而在美国东部则显然晚了差不多6000年。就其他6个候补地区而言,最早的得到充分证明的年代没有超过西南亚的年代,但在这其他的6个地区由于能够有把握确定其年代的遗址太少,我们无法肯定它们真的落后于西南亚以及(如果真的落后的话)落后多少。

| Examples of Species Domesticated in Each Area | |||

| 每一地区驯化物种举例 | |||

| Area | Domesticated Plants |

Domesticated Animals |

Earliest Attested Date of Domestication |

| 地区 | 驯化的植物 | 驯化的动物 | 得到证明的 最早的驯化年代 |

| Independent Origins of Domestication | |||

| 独立驯化的发源地 | |||

| 1 Southwest Asia | wheat, pea, olive | sheep, goat | 8500 B.C. |

| 西南亚 | 小麦、豌豆、橄榄 | 绵羊、山羊 | BC 8500 |

| 2 China | rice, millet | pig, silkworm | by 7500 B.C. |

| 中国 | 稻、黍 | 猪、蚕 | 不迟于BC 7500 |

| 3 Mesoamerica | corn, beans, squash | turkey | by 3500 B.C. |

| 中美洲 | 玉米、豆、南瓜属植物 | 火鸡 | 不迟于BC 3500 |

| 4 Andes and Amazonia | potato, manioc | llama, guinea pig | by 3500 B.C. |

| 安第斯山脉和亚马逊地区 | 马铃薯、木薯 | 羊驼、豚鼠 | 不迟于BC 3500 |

| 5 Eastern United States | sunflower, goosefoot | none | 2500 B.C. |

| 美国东部 | 向日葵、藜属植物 | 无 | BC 2500 |

| 6 ? Sahel | sorghum, African rice | guinea fowl | by 5000 B.C. |

| 萨赫勒地带 | 高粱、非洲稻 | 珍珠鸡 | 不迟于BC 5000 |

| 7 ? Tropical West Africa | African yams,oil palm | none | by 3000 B.C. |

| 热带西非 | 非洲薯蓣、油椰 | 无 | 不迟于BC 3000 |

| 8 ? Ethiopia | coffee, teff | none | ? |

| 埃塞俄比亚 | 咖啡、画眉草 | 无 | ? |

| 9 ? New Guinea | sugar cane, banana | none | 7000 B.C.? |

| 新几内亚 | 甘蔗、香蕉 | 无 | BC 7000 ? |

| Local Domestication Following Arrival of Founder Crops from Elsewhere | |||

| 在从别处引进祖代作用后在本地进行的驯化 | |||

| 10 Western Europe | poppy, oat | none | 6000–3500 B.C. |

| 西欧 | 罂粟、燕麦 | BC 6000-3500 | |

| 11 Indus Valley | sesame, eggplant | humped cattle | 7000 B.C. |

| 印度河河谷 | 芝麻、茄子 | 瘤牛 | BC 7000 |

| 12 Egypt | sycamore fig, chufa | donkey, cat | 6000 B.C. |

| 埃及 | 西克莫无花果、铁荸荠 | 驴、猫 | BC 6000 |

|

备注:7-12这6个地区由于能够有把握确定其年代的遗址太少,无法肯定(碳-14测定) 它们真的落后于西南亚以及(如果真的落后的话)落后多少? |

|||

| Examples of Species Domesticated in Each Area | |||

| Area | Domesticated Plants | Domesticated Animals | Earliest Attested? Date of Domestication |

| Independent Origins of Domestication | |||

| 1. Southwest Asia | wheat, pea, olive | sheep, goat | 8500 B.C. |

| 2. China | rice, millet | pig, silkworm | by 7500 B.C. |

| 3. Mesoamerica | corn, beans, squash | turkey | by 3500 B.C. |

| 4. Andes and Amazonia | potato, manioc | llama, guinea pig | by 3500 B.C. |

| 5. Eastern United States | sunflower, goosefoot | none | 2500 B.C. |

| ? 6. Sahel | sorghum, African rice | guinea fowl | by 5000 B.C. |

| ? 7. Tropical West Africa | African yams, oil palm | none | by 3000 B.C. |

| ? 8. Ethiopia | coffee, teff | none | ? |

| ? 9. New Guinea | sugar cane, banana | none | 7000 B.C.? |

| Local Domestication Following Arrival of Founder Crops from Elsewhere | |||

| 10. Western Europe | poppy, oat | none | 6000–3500 B.C. |

| 11. Indus Valley | sesame, eggplant | humped cattle | 7000 B.C. |

| 12. Egypt | sycamore fig, chufa | donkey, cat | 6000 B.C. |

| 每一地区驯化物种举例 | |||

| 地区 | 驯化的植物 | 驯化的动物 | 得到证明的 最早的驯化年代 |

| 独立驯化的发源地 | |||

| 1 西南亚 | 小麦、豌豆、橄榄 | 绵羊、山羊 | BC 8500 |

| 2 中国 | 稻、黍 | 猪、蚕 | 不迟于BC 7500 |

| 3 中美洲 | 玉米、豆、南瓜属植物 | 火鸡 | 不迟于BC 3500 |

| 4 安第斯山脉和亚马逊地区 | 马铃薯、木薯 | 羊驼、豚鼠 | 不迟于BC 3500 |

| 5 美国东部 | 向日葵、藜属植物 | 无 | BC 2500 |

| ? 6 萨赫勒地带 | 高粱、非洲稻 | 珍珠鸡 | 不迟于BC 5000 |

| ? 7 热带西非 | 非洲薯蓣、油椰 | 无 | 不迟于BC 3000 |

| ? 8 埃塞俄比亚 | 咖啡、画眉草 | 无 | ? |

| ? 9 新几内亚 | 甘蔗、香蕉 | 无 | BC 7000 ? |

| 在从别处引进祖代作用后在本地进行的驯化 | |||

| 10 西欧 | 罂粟、燕麦 | BC 6000-3500 | |

| 11 印度河河谷 | 芝麻、茄子 | 瘤牛 | BC 7000 |

| 12 埃及 | 西克莫无花果、铁荸荠 | 驴、猫 | BC 6000 |

The next group of areas consists of ones that did domesticate at least a couple of local plants or animals, but where food production depended mainly on crops and animals that were domesticated elsewhere. Those imported domesticates may be thought of as “founder” crops and animals, because they founded local food production. The arrival of founder domesticates enabled local people to become sedentary, and thereby increased the likelihood of local crops' evolving from wild plants that were gathered, brought home and planted accidentally, and later planted intentionally.

下一批地区包括一些至少驯化了两三种本地植物或动物的地区,但这些地区的粮食生产主要依靠在别处驯化的作物和动物。可以把这些引进的驯化动植物看作是“祖代”作物和动物,因为它们创立了本地的粮食生产。祖代驯化动植物的引进使本地人过着定居的生活,从而增加了野生植物演化为本地作物的可能性,这些野生植物本来是他们采集后带回家偶然种下的,而到后来就是有意种植了。

In three or four such areas, the arriving founder package came from Southwest Asia. One of them is western and central Europe, where food production arose with the arrival of Southwest Asian crops and animals between 6000 and 3500 B.C., but at least one plant (the poppy, and probably oats and some others) was then domesticated locally. Wild poppies are confined to coastal areas of the western Mediterranean. Poppy seeds are absent from excavated sites of the earliest farming communities in eastern Europe and Southwest Asia; they first appear in early farming sites in western Europe. In contrast, the wild ancestors of most Southwest Asian crops and animals were absent from western Europe. Thus, it seems clear that food production did not evolve independently in western Europe. Instead, it was triggered there by the arrival of Southwest Asian domesticates. The resulting western European farming societies domesticated the poppy, which subsequently spread eastward as a crop.

在三四个这样的地区,引进的祖代动植物来自西南亚。其中一个地区是欧洲的西部和中部,那里的粮食生产是在公元前6000年和3500年之间随着西南亚作物和动物的引进而出现的,但至少有一种植物(罂粟,可能还有燕麦和其他植物)当时是在本地驯化的。野生罂粟只生长在地中海西部沿岸地区。欧洲东部和西南亚最早的农业社会的发掘遗址中没有发现罂粟的种子;它们的首次出现是在欧洲西部的一些早期农村遗址。与此形成对照的是,在欧洲西部却没有发现西南亚大多数作物和动物的野生祖先。因此,粮食生产不是在欧洲西部独立发展起来的,这看来是很清楚的。相反,那里的粮食生产是由于引进了西南亚的驯化动植物而引发的。由此而产生的欧洲西部农业社会驯化了罂粟,随后罂粟就作为一种作物向东传播。

Another area where local domestication appears to have followed the arrival of Southwest Asian founder crops is the Indus Valley region of the Indian subcontinent. The earliest farming communities there in the seventh millennium B.C. utilized wheat, barley, and other crops that had been previously domesticated in the Fertile Crescent and that evidently spread to the Indus Valley through Iran. Only later did domesticates derived from indigenous species of the Indian subcontinent, such as humped cattle and sesame, appear in Indus Valley farming communities. In Egypt as well, food production began in the sixth millennium B.C. with the arrival of Southwest Asian crops. Egyptians then domesticated the sycamore fig and a local vegetable called chufa.

还有一个地区,那里由本地对动植物进行驯化,似乎是在引进西南亚的祖代作物后开始的。这个地区就是印度次大陆的印度河河谷地区。那里的农业社会出现在公元前的第七个1000中,它们利用的小麦、大麦和其他作物,是先前在新月沃地驯化的,然后显然再通过伊朗传播到印度河河谷。只是到了后来,由印度次大陆土生物种驯化的动植物,如瘤牛和芝麻,才在印度河河谷的农业社会出现。同样,在埃及,粮食生产也是在公元前6000年随着西南亚作物的引进而开始的。埃及人当时驯化了西克莫无花果和一种叫做铁荸荠的植物。

The same pattern perhaps applies to Ethiopia, where wheat, barley, and other Southwest Asian crops have been cultivated for a long time. Ethiopians also domesticated many locally available wild species to obtain crops most of which are still confined to Ethiopia, but one of them (the coffee bean) has now spread around the world. However, it is not yet known whether Ethiopians were cultivating these local plants before or only after the arrival of the Southwest Asian package.

同样的模式大概也适用于埃塞俄比亚,那里种植小麦、大麦和其他西南亚作物已有很长的历史。为了得到作物,埃塞俄比亚人也驯化了许多可在本地得到的物种,这些作物中的大多数仍然只有埃塞俄比亚才有,但其中的一种(咖啡豆)现在已传播到全世界。然而,埃塞俄比亚人驯化这些本地植物是在西南亚驯化物种引进之前还是在引进之后,这仍然无从知晓。

In these and other areas where food production depended on the arrival of founder crops from elsewhere, did local hunter-gatherers themselves adopt those founder crops from neighboring farming peoples and thereby become farmers themselves? Or was the founder package instead brought by invading farmers, who were thereby enabled to outbreed the local hunters and to kill, displace, or outnumber them?

在依靠从别处引进祖代作物来发展粮食生产的这些地区和其他地区,当地的狩猎采集族群是否从邻近的农业族群那里采纳了那些祖代作物,从而使他们自己也成了农民?或者,这一揽子祖代作物竟是由入侵的农民带来,从而使他们能够在当地以更快的速度繁衍,并杀死、赶走或在人数上超过本地的猎人?

In Egypt it seems likely that the former happened: local hunter-gatherers simply added Southwest Asian domesticates and farming and herding techniques to their own diet of wild plants and animals, then gradually phased out the wild foods. That is, what arrived to launch food production in Egypt was foreign crops and animals, not foreign peoples. The same may have been true on the Atlantic coast of Europe, where local hunter-gatherers apparently adopted Southwest Asian sheep and cereals over the course of many centuries. In the Cape of South Africa the local Khoi hunter-gatherers became herders (but not farmers) by acquiring sheep and cows from farther north in Africa (and ultimately from Southwest Asia). Similarly, Native American hunter-gatherers of the U.S. Southwest gradually became farmers by acquiring Mexican crops. In these four areas the onset of food production provides little or no evidence for the domestication of local plant or animal species, but also little or no evidence for the replacement of human population.

在埃及,似乎有可能发生前一种情况:本地的狩猎采集族群原来都是以野生动植物为食,现在又有了西南亚的驯化动植物和农牧技术,于是就逐步停止吃野生食物。这就是说,使粮食生产得以在埃及开始的是外来的作物和动物,而不是外来族群。在欧洲大西洋沿岸地区,情况也可能如此,因为那里的狩猎采集族群在许多世纪中显然采纳了西南亚的绵羊和谷物。在南非的好望角地区,以狩猎采集为生的科伊族人,由于从遥远的非洲北部(归根到底还是从西南亚)得到了绵羊和牛而成为牧人(而不是农民)。同样,美国西南部的以狩猎采集为生的印第安人,由于获得了墨西哥的作物而成为农民。在这4个地区,粮食生产的开始几乎没有或根本没有提供任何说明当地动植物驯化的证据,也几乎没有或根本没有提供任何说明人口更替的证据。

At the opposite extreme are regions in which food production certainly began with an abrupt arrival of foreign people as well as of foreign crops and animals. The reason why we can be certain is that the arrivals took place in modern times and involved literate Europeans, who described in innumerable books what happened. Those areas include California, the Pacific Northwest of North America, the Argentine pampas, Australia, and Siberia. Until recent centuries, these areas were still occupied by hunter-gatherers—Native Americans in the first three cases and Aboriginal Australians or Native Siberians in the last two. Those hunter-gatherers were killed, infected, driven out, or largely replaced by arriving European farmers and herders who brought their own crops and did not domesticate any local wild species after their arrival (except for macadamia nuts in Australia). In the Cape of South Africa the arriving Europeans found not only Khoi hunter-gatherers but also Khoi herders who already possessed only domestic animals, not crops. The result was again the start of farming dependent on crops from elsewhere, a failure to domesticate local species, and a massive modern replacement of human population.

另一个极端情况是:有些地区的粮食生产毫无疑问不但是从外来作物和动物的引进开始的,而且也是从外来人的突然到来开始的。我们之所以能如此肯定,是因为外来人的到来在现代也发生过,而且也与有文化的欧洲人直接有关,这些欧洲人在许多书中对所发生的事都有过描述。上面说的这些地区包括加利福尼亚、北美洲西北部太平洋沿岸、阿根廷的无树大草原、澳大利亚和西伯利亚。直到最近几个世纪,这些地区仍然为狩猎采集族群所占有——在前3个地区是美洲土著,在后两个地区是澳大利亚土著或西伯利亚土著。这些以狩猎采集为生的人遭到了陆续来到的欧洲农民和牧人的杀害、疾病的感染、驱逐、或大规模的更替。这些农民和牧人带来了他们自己的作物,所以在来到后没有对当地的任何野生物种进行驯化(澳大利亚的坚果树例外)。在南非的好望角地区,陆续来到的欧洲人不但发现了科伊族中以狩猎采集为生的人,也发现了科伊族中只有驯化动物而没有作物的牧人。结果仍然是:靠外来作物来开始农业,不驯化本地动物,以及现代人口的大规模更替。

Finally, the same pattern of an abrupt start of food production dependent on domesticates from elsewhere, and an abrupt and massive population replacement, seems to have repeated itself in many areas in the prehistoric era. In the absence of written records, the evidence of those prehistoric replacements must be sought in the archaeological record or inferred from linguistic evidence. The best-attested cases are ones in which there can be no doubt about population replacement because the newly arriving food producers differed markedly in their skeletons from the hunter-gatherers whom they replaced, and because the food producers introduced not only crops and animals but also pottery. Later chapters will describe the two clearest such examples: the Austronesian expansion from South China into the Philippines and Indonesia (Chapter 17), and the Bantu expansion over subequatorial Africa (Chapter 19).

最后,依靠外来作物来突然开始粮食生产和突然发生大规模的人口更替,这同一模式在史前时代的许多地区似乎多次出现过。由于缺乏文字记载,关于史前人口更替的证据必须从考古记录中去寻找,或者根据语言学的证据来加以推断。得到最充分证明的一些事例表明,人口更替现象毫无疑问是存在的,因为新来乍到的粮食生产者在骨骼方面同被他们更替的以狩猎采集为生的人有着显著的差异,同时也因为这些粮食生产者不但引进了作物和动物,也引进了陶器。以后的几章将对两个最明显的例子加以描述:南岛人从华南向菲律宾和印度尼西亚的扩张(第十七章)和班图人在非洲赤道以南地区的扩张(第十九章)。

Southeastern Europe and central Europe present a similar picture of an abrupt onset of food production (dependent on Southwest Asian crops and animals) and of pottery making. This onset too probably involved replacement of old Greeks and Germans by new Greeks and Germans, just as old gave way to new in the Philippines, Indonesia, and subequatorial Africa. However, the skeletal differences between the earlier hunter-gatherers and the farmers who replaced them are less marked in Europe than in the Philippines, Indonesia, and subequatorial Africa. Hence the case for population replacement in Europe is less strong or less direct.

东南欧和中欧使我们看到了一幅类似的图景,即粮食生产(依靠西南亚的作物和动物)和制陶的突然开始。这种突然的开始大概也与古希腊人和日耳曼人被现代希腊人和日耳曼人所更替直接有关,就像在菲律宾、印度尼西亚和非洲赤道以南地区旧有的人让位于新来的人一样。然而,原来的以狩猎采集为生的人和更替他们的农民在骨骼方面的差异,在欧洲不像在菲律宾、印度尼西亚和非洲赤道以南地区那样显著。因此,在欧洲人口更替的例子也就不那么有说服力或不那么直接了。

IN SHORT, ONLY a few areas of the world developed food production independently, and they did so at widely differing times. From those nuclear areas, hunter-gatherers of some neighboring areas learned food production, and peoples of other neighboring areas were replaced by invading food producers from the nuclear areas—again at widely differing times. Finally, peoples of some areas ecologically suitable for food production neither evolved nor acquired agriculture in prehistoric times at all; they persisted as hunter-gatherers until the modern world finally swept upon them. The peoples of areas with a head start on food production thereby gained a head start on the path leading toward guns, germs, and steel. The result was a long series of collisions between the haves and the have-nots of history.

总之,世界上只有几个地区发展了粮食生产,而且这些地区发展粮食生产的时间也差异甚大。一些邻近地区的狩猎采集族群从这些核心地区学会了粮食生产,而其他一些邻近地区的族群则被来自这些核心地区的粮食生产者所更替了——更替的时间仍然差异甚大。最后,有些族群虽然生活在一些生态条件适于粮食生产的地区,但他们在史前期既没有发展出农业,也没有学会农业;他们始终以狩猎采集为生,直到现代世界最后将他们淘汰。在粮食生产上具有领先优势的那些地区里的族群,因而在通往枪炮、病菌和钢铁的道路上也取得了领先的优势。其结果就是富有社会与贫穷社会之间一系列的长期冲突。

How can we explain these geographic differences in the times and modes of onset of food production? That question, one of the most important problems of prehistory, will be the subject of the next five chapters.

我们怎样来解释粮食生产的开始在时间和模式上的地理差异呢?这个问题是关于史前史的最重要的问题之一,它将成为下面五章讨论的主题。

注释:

1. 萨赫勒地带:阿拉伯语意为“沙漠之边”,指撒哈拉沙漠南沿的一条广阔的半沙漠地带,跨乍得、冈比亚、马里、毛里塔尼亚、尼日尔、塞内加尔和布基纳法索等国境。——译者