CHAPTER 8

第八章

APPLES OR INDIANS

问题在苹果还是在印第安人

WE HAVE JUST SEEN HOW PEOPLES OF SOME REGIONS began to cultivate wild plant species, a step with momentous unforeseen consequences for their lifestyle and their descendants' place in history. Let us now return to our questions: Why did agriculture never arise independently in some fertile and highly suitable areas, such as California, Europe, temperate Australia, and subequatorial Africa? Why, among the areas where agriculture did arise independently, did it develop much earlier in some than in others?

我们刚才已经看到,某些地区的人是怎样开始培育野生植物的。对于这些人的生活方式和他们的子孙后代在历史上的地位来说,这是重大的、难以预见其后果的一步。现在,让我们再回到我们原来的问题:为什么农业没有在一些肥沃的十分合适的地区,如加利福尼亚、欧洲、气候温和的澳大利亚以及非洲赤道以南地区独立地出现?而在农业独立出现的那些地区中,为什么有些地区的农业发展会比另一些地区早得多?

Two contrasting explanations suggest themselves: problems with the local people, or problems with the locally available wild plants. On the one hand, perhaps almost any well-watered temperate or tropical area of the globe offers enough species of wild plants suitable for domestication. In that case, the explanation for agriculture's failure to develop in some of those areas would lie with cultural characteristics of their peoples. On the other hand, perhaps at least some humans in any large area of the globe would have been receptive to the experimentation that led to domestication. Only the lack of suitable wild plants might then explain why food production did not evolve in some areas.

这使我们想到了两个形成对比的解释:当地人的问题,或当地可以得到的野生植物的问题。一方面,也许地球上几乎任何水分充足、气候温和的地区或热带地区,都有足够的适于驯化的野生植物物种。在这种情况下,对农业未能在其中某些地区发展起来的解释,可能在于这些地区的人的民族文化特点。另一方面,也许在地球上任何一个广大的地区,至少有某些人可能已迅速接受了导致驯化的实验。因此,只有缺乏适当的野生植物,可以解释为什么粮食生产没有在某些地区发展起来。

As we shall see in the next chapter, the corresponding problem for domestication of big wild mammals proves easier to solve, because there are many fewer species of them than of plants. The world holds only about 148 species of large wild mammalian terrestrial herbivores or omnivores, the large mammals that could be considered candidates for domestication. Only a modest number of factors determines whether a mammal is suitable for domestication. It's thus straightforward to review a region's big mammals and to test whether the lack of mammal domestication in some regions was due to the unavailability of suitable wild species, rather than to local peoples.

我们将在下一章看到,与此相对应的对大型野生哺乳动物的驯化问题,却证明比较容易解决,因为它们的种类比植物少得多。世界上只有大约148种大型野生哺乳类陆生食草动物或杂食动物,它们是可以被认为有可能驯化的大型哺乳动物。只有不多的因素能够决定某种哺乳动物是否适于驯化。因此,直截了当的办法就是去考察某一地区的大型哺乳动物,并分析一下某些地区缺乏对哺乳动物的驯化是否是由于不能得到合适的野生品种,而不是由于当地的人。

That approach would be much more difficult to apply to plants because of the sheer number—200,000—of species of wild flowering plants, the plants that dominate vegetation on the land and that have furnished almost all of our crops. We can't possibly hope to examine all the wild plant species of even a circumscribed area like California, and to assess how many of them would have been domesticable. But we shall now see how to get around that problem.

把这种办法应用于植物可能要困难得多,因为植物的数量太大,光是会开花的野生植物就有20万种,它们在陆地植物中占据首要地位,并成为我们的几乎全部作物的来源。甚至在像加利福尼亚这样的限定地区内,我们也不可能指望把所有野生动物考察一遍,并评估一下其中有多少是可驯化的。不过,我们现在可以来看一看这个问题是怎样解决的。

WHEN ONE HEARS that there are so many species of flowering plants, one's first reaction might be as follows: surely, with all those wild plant species on Earth, any area with a sufficiently benign climate must have had more than enough species to provide plenty of candidates for crop development.

如果有人听说竟有那么多种开花植物,他的第一个反应可能就是这样:地球上既然有那么多种的野生植物,那么任何地区只要有足够好的气候,野生植物就必定十分丰富,足以为培育作物提供大量具有候选资格的植物品种。

But then reflect that the vast majority of wild plants are unsuitable for obvious reasons: they are woody, they produce no edible fruit, and their leaves and roots are also inedible. Of the 200,000 wild plant species, only a few thousand are eaten by humans, and just a few hundred of these have been more or less domesticated. Even of these several hundred crops, most provide minor supplements to our diet and would not by themselves have sufficed to support the rise of civilizations. A mere dozen species account for over 80 percent of the modern world's annual tonnage of all crops. Those dozen blockbusters are the cereals wheat, corn, rice, barley, and sorghum; the pulse soybean; the roots or tubers potato, manioc, and sweet potato; the sugar sources sugarcane and sugar beet; and the fruit banana. Cereal crops alone now account for more than half of the calories consumed by the world's human populations. With so few major crops in the world, all of them domesticated thousands of years ago, it's less surprising that many areas of the world had no wild native plants at all of outstanding potential. Our failure to domesticate even a single major new food plant in modern times suggests that ancient peoples really may have explored virtually all useful wild plants and domesticated all the ones worth domesticating.

但是,如果真是那样,请考虑一下大多数野生植物都是不合适的,原因很明显:它们是木本植物,它们不出产任何可吃的果实,它的叶和根也是不能吃的。在这20万种野生植物中,只有几千种可供人类食用,只有几百种得到或多或少的驯化。即使在这几百种作物中,大多数作物只是对我们的饮食的次要的补充,光靠它们还不足以支持文明的兴起。仅仅十几种作物的产量,就占去了现代世界全部作物年产量总吨数的80%以上。这十几种了不起的作物是谷类中的小麦、玉米、稻米、大麦和高粱;豆类中的大豆;根或块茎中的马铃薯、木薯和甘薯;糖料作物中的甘蔗和糖用甜菜;以及水果中的香蕉。光是谷类作物现在就占去了全世界人口所消费的卡路里的一半以上。由于世界上的主要作物如此之少,它们又都是在几千年前驯化的,所以世界上的许多地区根本就不曾有过任何具有显著潜力的本地野生植物,这就不足为奇了。我们在现代没有能驯化甚至一种新的重要的粮食植物,这种情况表明,古代人也许真的探究了差不多所有有用的野生植物,并且驯化了所有值得驯化的野生植物。

Yet some of the world's failures to domesticate wild plants remain hard to explain. The most flagrant cases concern plants that were domesticated in one area but not in another. We can thus be sure that it was indeed possible to develop the wild plant into a useful crop, and we have to ask why that wild species was not domesticated in certain areas.

然而,世界上有些地方何以未能驯化野生植物,这个问题仍然难以解释。这方面最明显的例子是,有些植物在一个地区驯化了,却没有在另一地区驯化。因此,我们能够确信,的确有可能把野生植物培育成有用的作物,但同时也必须问一问:那个野生植物为什么在某些地区不能驯化?

A typical puzzling example comes from Africa. The important cereal sorghum was domesticated in Africa's Sahel zone, just south of the Sahara. It also occurs as a wild plant as far south as southern Africa, yet neither it nor any other plant was cultivated in southern Africa until the arrival of the whole crop package that Bantu farmers brought from Africa north of the equator 2,000 years ago. Why did the native peoples of southern Africa not domesticate sorghum for themselves?

一个令人困惑的典型例子来自非洲。重要的谷物高粱在非洲撒哈拉沙漠南沿的萨赫勒地带驯化了。南至非洲南部也有野生高粱存在,但无论是高粱还是任何其他植物,在非洲南部都没有人栽种,直到2000年前班图族农民才从赤道以北的非洲地区引进了一整批作物。为什么非洲南部的土著没有为自己去驯化高粱呢?

Equally puzzling is the failure of people to domesticate flax in its wild range in western Europe and North Africa, or einkorn wheat in its wild range in the southern Balkans. Since these two plants were among the first eight crops of the Fertile Crescent, they were presumably among the most readily domesticated of all wild plants. They were adopted for cultivation in those areas of their wild range outside the Fertile Crescent as soon as they arrived with the whole package of food production from the Fertile Crescent. Why, then, had peoples of those outlying areas not already begun to grow them of their own accord?

同样令人困惑的是,人们未能驯化欧洲西部和北非的野生亚麻,也未能驯化巴尔干半岛南部的野生单粒小麦。既然这两种植物同属新月沃地最早的8大作物,它们也应该是所有野生植物中最容易驯化的两种植物。在它们随同整个粮食生产从新月沃地引进后,它们立即在新月沃地以外的这些野生产地被用来栽培。那么,这些边远地区的一些族群为什么不是早已主动地开始去种植它们呢?

Similarly, the four earliest domesticated fruits of the Fertile Crescent all had wild ranges stretching far beyond the eastern Mediterranean, where they appear to have been first domesticated: the olive, grape, and fig occurred west to Italy and Spain and Northwest Africa, while the date palm extended to all of North Africa and Arabia. These four were evidently among the easiest to domesticate of all wild fruits. Why did peoples outside the Fertile Crescent fail to domesticate them, and begin to grow them only when they had already been domesticated in the eastern Mediterranean and arrived thence as crops?

同样,新月沃地最早驯化的4种水果在远至东地中海以外地区都有野生产地,它们似乎最早在那里得到驯化:橄榄、葡萄和无花果往西出现在意大利、西班牙和西北非,而枣椰树则扩散到整个北非和阿拉伯半岛。这4种水果显然是所有野生水果中最容易驯化的。那么,为什么新月沃地的一些族群未能驯化它们,而只是在它们已在东地中海地区得到驯化并从那里作为作物引进之后才开始种植它们呢?

Other striking examples involve wild species that were not domesticated in areas where food production never arose spontaneously, even though those wild species had close relatives domesticated elsewhere. For example, the olive Olea europea was domesticated in the eastern Mediterranean. There are about 40 other species of olives in tropical and southern Africa, southern Asia, and eastern Australia, some of them closely related to Olea europea, but none of them was ever domesticated. Similarly, while a wild apple species and a wild grape species were domesticated in Eurasia, there are many related wild apple and grape species in North America, some of which have in modern times been hybridized with the crops derived from their wild Eurasian counterparts in order to improve those crops. Why, then, didn't Native Americans domesticate those apparently useful apples and grapes themselves?

其他一些引人注目的例子涉及这样一些野生植物:它们并没有在那些从未自发地出现粮食生产的地区得到驯化,虽然它们也有在其他地方得到驯化的近亲。例如,欧洲橄榄就是在东地中海地区驯化的。在热带非洲、非洲南部、亚洲南部和澳大利亚东部还有大约40种橄榄,其中有些还是欧洲橄榄的近亲,但没有一种得到驯化。同样,虽然有一种野苹果和野葡萄在欧亚大陆得到了驯化,但在北美洲还有许多有亲缘关系的野苹果和野葡萄,其中有些在现代已和来自欧亚大陆的野苹果和野葡萄进行了杂交,以改良这些作物的品种。那么,为什么美洲土著自己没有去驯化这些显然有用的苹果和葡萄呢?

One can go on and on with such examples. But there is a fatal flaw in this reasoning: plant domestication is not a matter of hunter-gatherers' domesticating a single plant and otherwise carrying on unchanged with their nomadic lifestyle. Suppose that North American wild apples really would have evolved into a terrific crop if only Indian hunter-gatherers had settled down and cultivated them. But nomadic hunter-gatherers would not throw over their traditional way of life, settle in villages, and start tending apple orchards unless many other domesticable wild plants and animals were available to make a sedentary food-producing existence competitive with a hunting-gathering existence.

这种例子可以说是不胜枚举。但这种推论有一个致命的缺点:植物驯化不是什么要么狩猎采集族群去驯化一种植物,要么就继续过他们原来那种流浪生活的问题。假定只要以狩猎采集为生的印第安人定居下来并栽培野苹果,那么北美洲的野苹果就的确会演化成为一种了不起的作物。但是,到处流浪的狩猎采集族群是不会抛弃他们传统的生活方式,在村子里定居下来并开始照料苹果园的,除非还有其他许多可以驯化的动植物可以利用来使定居的从事粮食生产的生存方式能够与狩猎采集的生存方式一争高下。

How, in short, do we assess the potential of an entire local flora for domestication? For those Native Americans who failed to domesticate North American apples, did the problem really he with the Indians or with the apples?

总之,我们怎样去评估某一地区整个植物群驯化的可能性?对于这些未能驯化北美洲苹果的印第安人来说,问题实际上是在印第安人还是在苹果?

In order to answer this question, we shall now compare three regions that lie at opposite extremes among centers of independent domestication. As we have seen, one of them, the Fertile Crescent, was perhaps the earliest center of food production in the world, and the site of origin of several of the modern world's major crops and almost all of its major domesticated animals. The other two regions, New Guinea and the eastern United States, did domesticate local crops, but these crops were very few in variety, only one of them gained worldwide importance, and the resulting food package failed to support extensive development of human technology and political organization as in the Fertile Crescent. In the light of this comparison, we shall ask: Did the flora and environment of the Fertile Crescent have clear advantages over those of New Guinea and the eastern United States?

为了回答这个问题,我们可以比较一下在独立的驯化中心中处于两个极端的3个地区。我们已经看到,其中一个地区就是新月沃地,它也许是世界上最早的粮食生产中心,也是现代世界主要作物中的几种作物以及几乎所有的主要驯化动物的发源地。另外两个地区是新几内亚和美国东部。这两个地区的确驯化过当地的作物,但这些作物品种很少,只有一种成为世界上的重要作物,而且由此产生的整个粮食也未能像在新月沃地那样帮助人类技术和行政组织的广泛发展。根据这个比较,我们不妨问一问:新月沃地的植物群和环境是否具有对新几内亚和美国东部的植物群和环境的明显优势?

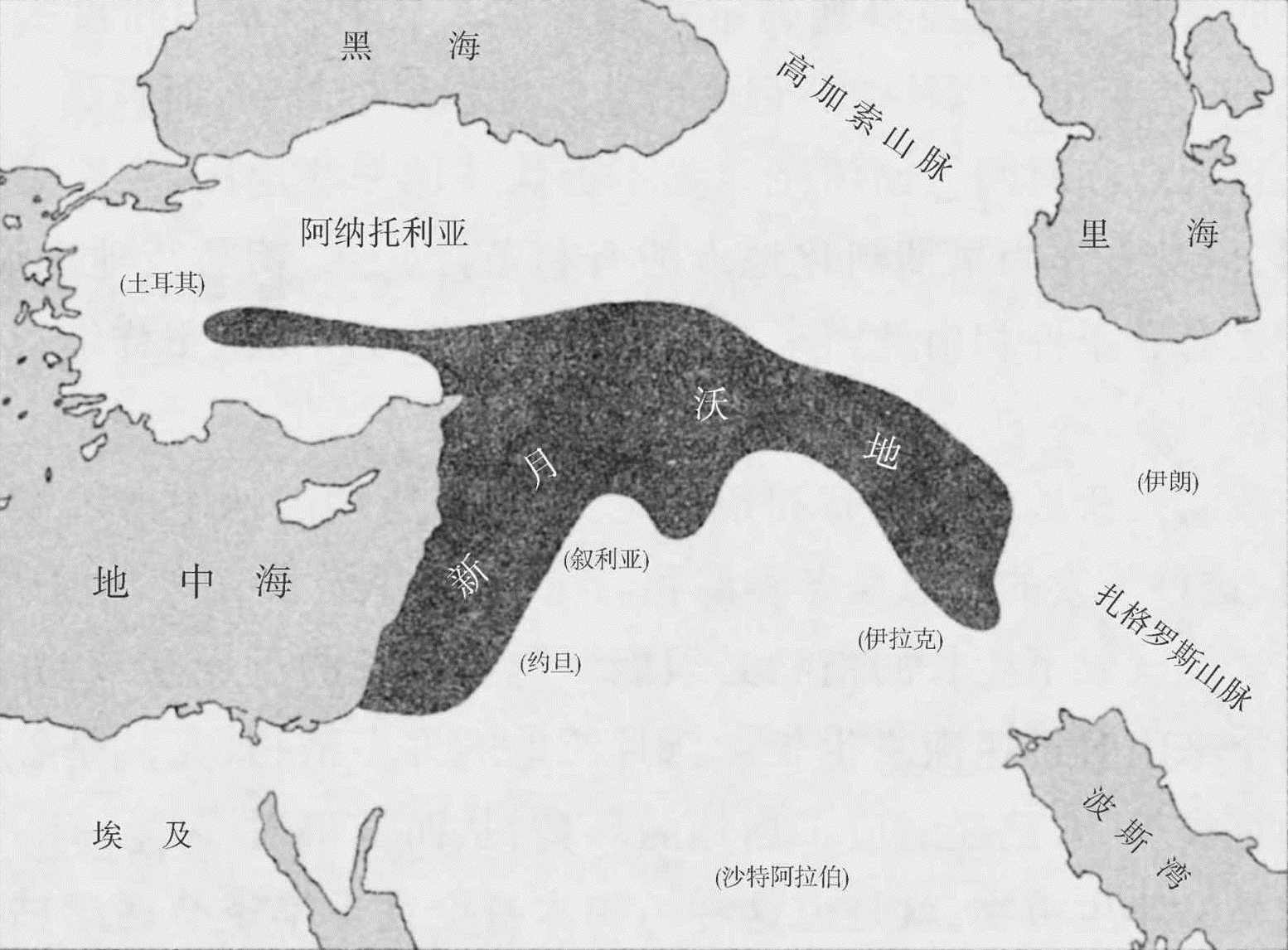

ONE OF THE central facts of human history is the early importance of the part of Southwest Asia known as the Fertile Crescent (because of the crescent-like shape of its uplands on a map: see Figure 8.1). That area appears to have been the earliest site for a whole string of developments, including cities, writing, empires, and what we term (for better or worse) civilization. All those developments sprang, in turn, from the dense human populations, stored food surpluses, and feeding of nonfarming specialists made possible by the rise of food production in the form of crop cultivation and animal husbandry. Food production was the first of those major innovations to appear in the Fertile Crescent. Hence any attempt to understand the origins of the modern world must come to grips with the question why the Fertile Crescent's domesticated plants and animals gave it such a potent head start.

人类历史的主要事实之一,是西南亚的那个叫做新月沃地的地区(因其在地图上的新月状高地而得名,见图8.1)在人类发展早期的重要性。那个地区似乎是包括城市、文字、帝国以及我们所说的文明(不论是福是祸)在内的一连串新情况发生的地方。而所有这些新情况之所以发生,都是由于有了稠密的人口,有了剩余粮食的贮存,以及可以养活不从事农业的专门人材,凡此种种之所以可能又都是由于出现了以作物栽培和牲口饲养为形式的粮食生产。粮食生产是新月沃地出现的那些重要新事物中的第一个新事物。因此,如果想要了解现代世界的由来,就必须认真对待这样的问题,即为什么新月沃地的驯化动植物使它获得了如此强大的领先优势。

Fortunately, the Fertile Crescent is by far the most intensively studied and best understood part of the globe as regards the rise of agriculture. For most crops domesticated in or near the Fertile Crescent, the wild plant ancestor has been identified; its close relationship to the crop has been proven by genetic and chromosomal studies; its wild geographic range is known; its changes under domestication have been identified and are often understood at the level of single genes; those changes can be observed in successive layers of the archaeological record; and the approximate place and time of domestication are known. I don't deny that other areas, notably China, also had advantages as early sites of domestication, but those advantages and the resulting development of crops can be specified in much more detail for the Fertile Crescent.

幸运的是,就农业的兴起而论,新月沃地显然是地球上研究得最为详尽和了解得最为透彻的地区。对在新月沃地或其邻近地区驯化的大多数作物来说,其野生祖先已经得到认定;野生祖先与作物的密切关系已经通过遗传和染色体的研究而得到证明;野生祖先的地理分布已经确知;野生祖先在驯化条件下所产生的种种变化已经得到确定并经常被人从单一基因角度去认识;这些变化可以从考古记录的连续堆积层中看到;而且驯化的大致地点和时间也已清楚。我不否认其他一些地区,主要是中国,也具有作为早期驯化地点的有利条件,但对新月沃地来说,这些有利条件和由此而来的作物的发展却可以得到更详细得多的说明。

Firgure 8.1. The Fertile Crescent, encompassing sites of food production before 7000 B.C.

图8.1新月沃地,包含有公元前7000年的一些粮食生产地。

One advantage of the Fertile Crescent is that it lies within a zone of so-called Mediterranean climate, a climate characterized by mild, wet winters and long, hot, dry summers. That climate selects for plant species able to survive the long dry season and to resume growth rapidly upon the return of the rains. Many Fertile Crescent plants, especially species of cereals and pulses, have adapted in a way that renders them useful to humans: they are annuals, meaning that the plant itself dries up and dies in the dry season.

新月沃地的一个有利条件是:它地处所谓的地中海气候带内,这种气候的特点是冬季温和而湿润,夏季漫长、炎热而干燥。在这种气候下生长的植物必须能够熬过漫长的干燥季节,并在雨季来临时迅速恢复生长。新月沃地的许多植物,尤其是谷类和豆类植物,已经适应了当地的环境,从而变得对人类有用:它们是一年生植物,就是说这种植物本身会在干旱季节逐渐枯萎死去。

Within their mere one year of life, annual plants inevitably remain small herbs. Many of them instead put much of their energy into producing big seeds, which remain dormant during the dry season and are then ready to sprout when the rains come. Annual plants therefore waste little energy on making inedible wood or fibrous stems, like the body of trees and bushes. But many of the big seeds, notably those of the annual cereals and pulses, are edible by humans. They constitute 6 of the modern world's 12 major crops. In contrast, if you live near a forest and look out your window, the plant species that you see will tend to be trees and shrubs, most of whose body you cannot eat and which put much less of their energy into edible seeds. Of course, some forest trees in areas of wet climate do produce big edible seeds, but these seeds are not adapted to surviving a long dry season and hence to long storage by humans.

由于只有一年的生命,一年生植物必然是矮小的草本植物。其中有许多把自己的很大一部分气力用来生产大籽粒的种子,种子在旱季休眠,并准备好在雨季到来时发芽。因此,一年生植物不会浪费气力去生长不可食用的木质部或纤维梗茎,就像乔木和灌木的枝干那样。但是许多大籽粒的种子,主要是一年生谷物和豆类的种子,是可以供人类食用的。它们构成了现代世界的12种主要作物中的6种。相比之下,如果你住在森林旁边并凭窗远眺,那么你所看到的植物往往都是乔木和灌木,其中大多数植物的枝干都是不能食用的,它们也很少把气力花在生产可供食用的种子上。当然,在气候湿润地区的森林里,有些树木的确产生了可供食用的大种子,但这些种子的适应能力还不能使它们度过漫长的旱季,因而不适合人类的长期贮藏。

A second advantage of the Fertile Crescent flora is that the wild ancestors of many Fertile Crescent crops were already abundant and highly productive, occurring in large stands whose value must have been obvious to hunter-gatherers. Experimental studies in which botanists have collected seeds from such natural stands of wild cereals, much as hunter-gatherers must have been doing over 10,000 years ago, show that annual harvests of up to nearly a ton of seeds per hectare can be obtained, yielding 50 kilocalories of food energy for only one kilocalorie of work expended. By collecting huge quantities of wild cereals in a short time when the seeds were ripe, and storing them for use as food through the rest of the year, some hunting-gathering peoples of the Fertile Crescent had already settled down in permanent villages even before they began to cultivate plants.

新月沃地植物群的另一个有利条件是:新月沃地许多作物的野生祖先本就繁茂而高产,它们大片大片地出现,对于狩猎采集族群来说,其价值必定是显而易见的。植物学家们进行了一些试验性的研究,从天然的大片野生谷物中采集种子,就像1万多年前狩猎采集族群所做的那样。这些研究表明,每年每公顷可以收获近一吨的种子,只要花费一个大卡的劳力就可产生50个大卡的食物能量。新月沃地的有些狩猎采集族群在种子成熟的短暂时间里采集大量的野生植物,并把它们作为粮食贮存起来以备一年中其余时间之需,这样,他们甚至在开始栽培植物之前就已在永久性的村庄里定居了下来。

Since Fertile Crescent cereals were so productive in the wild, few additional changes had to be made in them under cultivation. As we discussed in the preceding chapter, the principal changes—the breakdown of the natural systems of seed dispersal and of germination inhibition—evolved automatically and quickly as soon as humans began to cultivate the seeds in fields. The wild ancestors of our wheat and barley crops look so similar to the crops themselves that the identity of the ancestor has never been in doubt. Because of this ease of domestication, big-seeded annuals were the first, or among the first, crops developed not only in the Fertile Crescent but also in China and the Sahel.

由于新月沃地的谷物在野生状态中即已如此多产,人工栽培几乎没有给它们带来别的什么变化。我们在前一章里已经讨论过,主要的变化——种子传播和发芽抑制方面自然机制的破坏——在人类开始把种子种到田里之后立即自动而迅速地形成了。我们现在的小麦和大麦作物的野生祖先,同这些作物本身在外观上如此相似,使我们对野生祖先的身份从来不会有任何怀疑。由于驯化如此容易,大籽粒的一年生植物就成为不仅在新月沃地而且也在中国和萨赫勒地带培育出来的最早的作物或最早的作物之一。

Contrast this quick evolution of wheat and barley with the story of corn, the leading cereal crop of the New World. Corn's probable ancestor, a wild plant known as teosinte, looks so different from corn in its seed and flower structures that even its role as ancestor has been hotly debated by botanists for a long time. Teosinte's value as food would not have impressed hunter-gatherers: it was less productive in the wild than wild wheat, it produced much less seed than did the corn eventually developed from it, and it enclosed its seeds in inedible hard coverings. For teosinte to become a useful crop, it had to undergo drastic changes in its reproductive biology, to increase greatly its investment in seeds, and to lose those rock-like coverings of its seeds. Archaeologists are still vigorously debating how many centuries or millennia of crop development in the Americas were required for ancient corn cobs to progress from a tiny size up to the size of a human thumb, but it seems clear that several thousand more years were then required for them to reach modern sizes. That contrast between the immediate virtues of wheat and barley and the difficulties posed by teosinte may have been a significant factor in the differing developments of New World and Eurasian human societies.

请把小麦和大麦的这种迅速的演化同新大陆的首要谷类作物玉米的情况作一对比。玉米的可能祖先是一种叫做墨西哥类蜀黍的野生植物,它的种子和花的结构都和玉米不同,以致植物学家们长期以来一直在激烈争论它是否就是玉米的祖先。墨西哥类蜀黍作为食物的价值,可能没有给狩猎采集族群留下什么印象:它在野生状态下的产量不及野生小麦,它的种子也比最终从它演化出来的玉米少得多,而且它的种子外面还包着不能食用的硬壳。墨西哥类蜀黍要想成为一种有用的作物,就必须经历其生殖生物学的剧变,以大大增加种子的数量,并去掉种子外面的那些像石头一样的硬壳。考古学家们仍在激烈地争论,在美洲的作物发展过程中,古代的玉米棒究竟经过了多少个百年或千年才从一丁点儿大小发展到人的拇指那么大小,但有一点似乎是清楚的,那就是后来又经过了几千年它们才达到现代这么大小。一边是小麦和大麦的直接价值,一边是墨西哥类蜀黍所引起的种种困难,这两者之间的悬殊差别也许就是新大陆人类社会和欧亚大陆人类社会的发展差异的一个重要因素。

A third advantage of the Fertile Crescent flora is that it includes a high percentage of hermaphroditic “selfers”—that is, plants that usually pollinate themselves but that are occasionally cross-pollinated. Recall that most wild plants either are regularly cross-pollinated hermaphrodites or consist of separate male and female individuals that inevitably depend on another individual for pollination. Those facts of reproductive biology vexed early farmers, because, as soon as they had located a productive mutant plant, its offspring would cross-breed with other plant individuals and thereby lose their inherited advantage. As a result, most crops belong to the small percentage of wild plants that either are hermaphrodites usually pollinating themselves or else reproduce without sex by propagating vegetatively (for example, by a root that genetically duplicates the parent plant). Thus, the high percentage of hermaphroditic selfers in the Fertile Crescent flora aided early farmers, because it meant that a high percentage of the wild flora had a reproductive biology convenient for humans.

新月沃地植物群的第三个有利条件是:雌雄同株自花传粉的植物比例很高——就是说,它们通常是自花传粉,但偶尔也有异花传粉的。请回想一下,大多数野生植物或者是定期进行异花传粉的雌雄同株,或是必然要依靠另一个体传授花粉的雄性和雌性个体。生殖生物学的这些事实使早期农民感到困惑,因为他们刚刚找到了一种由突变产生的高产植物,它的后代可能因与其他植物杂交而失去其遗传优势。因此,大部分作物都来自少数野生植物。这些野生植物或者是通常自花传粉的雌雄同株,或者是靠无性繁殖来繁殖自己(例如,靠在遗传上复制亲代植物的根)。这样,新月沃地植物群中众多的雌雄同株自花传粉的植物就帮助了早期的农民,因为这意味着众多的野生植物群有了一种给人类带来方便的繁殖生物学。

Selfers were also convenient for early farmers in that they occasionally did become cross-pollinated, thereby generating new varieties among which to select. That occasional cross-pollination occurred not only between individuals of the same species, but also between related species to produce interspecific hybrids. One such hybrid among Fertile Crescent selfers, bread wheat, became the most valuable crop in the modern world.

自花传粉植物也给早期的农民带来了方便,因为这些植物偶尔也会异花传粉,从而产生了可供选择的新的植物品种。这种偶尔的异花传粉现象不仅发生在同种的一些个体之间,而且也发生在有亲缘关系的品种之间以产生种间杂种。新月沃地的自花传粉植物中的一个这样的杂种——面包小麦已经成为现代世界最有价值的作物。

Of the first eight significant crops to have been domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, all were selfers. Of the three selfer cereals among them—einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, and barley—the wheats offered the additional advantage of a high protein content, 8–14 percent. In contrast, the most important cereal crops of eastern Asia and of the New World—rice and corn, respectively—had a lower protein content that posed significant nutritional problems.

已在新月沃地驯化的最早的8种重要的作物,全都是自花传粉植物。其中3种是自花传粉的谷类作物——单粒小麦、二粒小麦和大麦,小麦具有额外的优势,即蛋白质含量高达8%-14%。相形之下,东亚和新大陆的最重要的谷类作物——分别为稻米和玉米——蛋白质含量较低,从而造成了重大的营养问题。

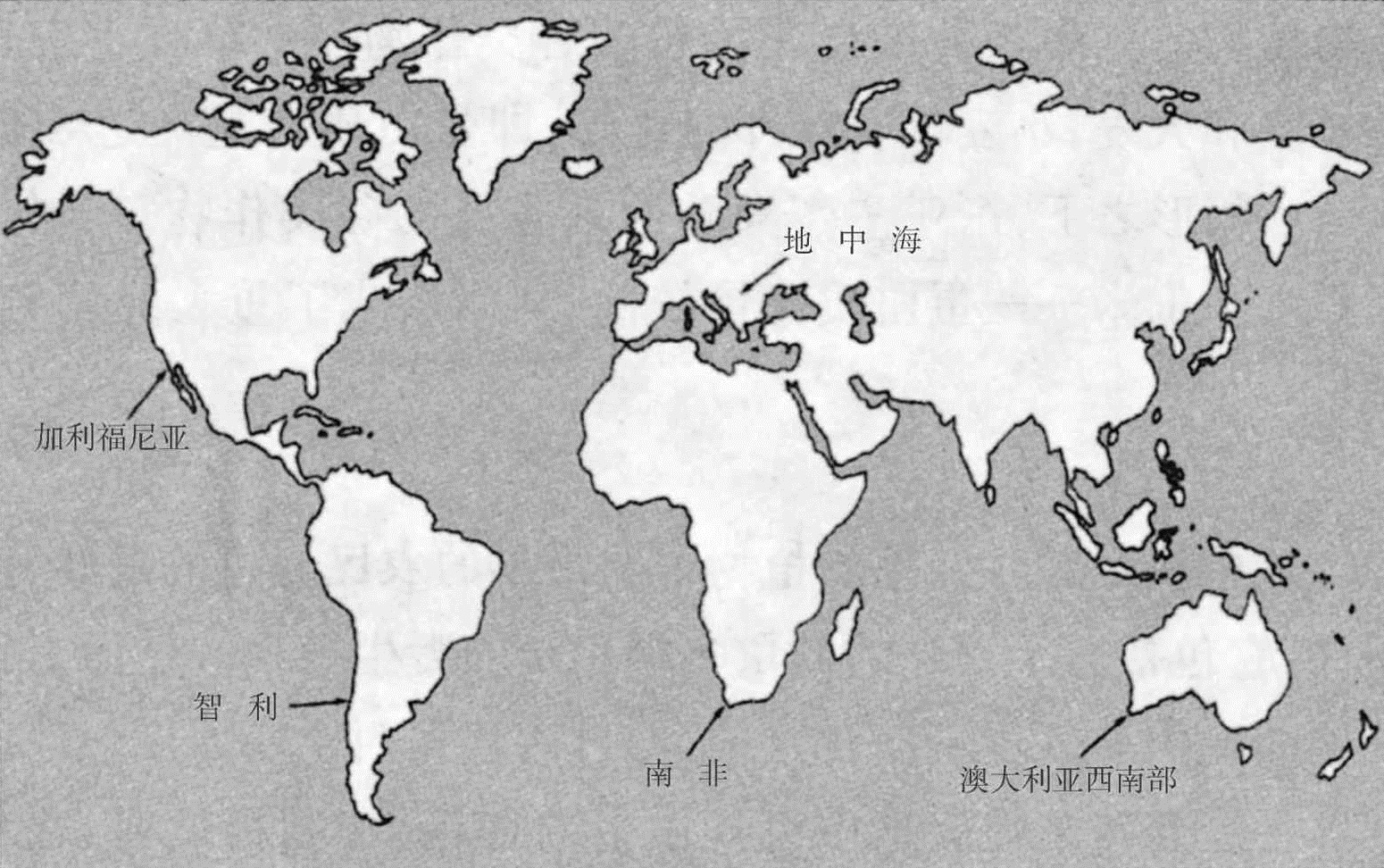

THOSE WERE SOME of the advantages that the Fertile Crescent's flora afforded the first farmers: it included an unusually high percentage of wild plants suitable for domestication. However, the Mediterranean climate zone of the Fertile Crescent extends westward through much of southern Europe and northwestern Africa. There are also zones of similar Mediterranean climates in four other parts of the world: California, Chile, southwestern Australia, and South Africa (Figure 8.2). Yet those other Mediterranean zones not only failed to rival the Fertile Crescent as early sites of food production; they never gave rise to indigenous agriculture at all. What advantage did that particular Mediterranean zone of western Eurasia enjoy?

这些就是新月沃地的植物群向最早的农民提供的一些有利条件:它包括适于驯化的数量多得出奇的野生植物。然而,新月沃地的地中海气候带向西延伸,经过南欧和西北非的广大地区。世界上还有4个类似地中海气候带的地区:加利福尼亚、智利、澳大利亚西南部和南非(图8.2)。然而,这些另外的地中海气候带不但无法赶上新月沃地而成为早期的出现粮食生产的地方;它们也根本没有产生过本地的农业。欧亚大陆西部的这种特有的地中海气候带究竟具有什么样的有利条件呢?

Figure 8.2. The world's zones of Mediterranean climate.

图8.2 世界上的地中海气候带。

It turns out that it, and especially its Fertile Crescent portion, possessed at least five advantages over other Mediterranean zones. First, western Eurasia has by far the world's largest zone of Mediterranean climate. As a result, it has a high diversity of wild plant and animal species, higher than in the comparatively tiny Mediterranean zones of southwestern Australia and Chile. Second, among Mediterranean zones, western Eurasia's experiences the greatest climatic variation from season to season and year to year. That variation favored the evolution, among the flora, of an especially high percentage of annual plants. The combination of these two factors—a high diversity of species and a high percentage of annuals—means that western Eurasia's Mediterranean zone is the one with by far the highest diversity of annuals.

原来地中海气候带,尤其是在新月沃地那个地区,具有胜过其他地中海气候带的5个有利条件。第一,欧亚大陆西部显然是世界上属于地中海气候带的最大地区。因此,那里的野生动植物品种繁多,超过了澳大利亚西南部和智利这些比较小的地中海气候带。第二,在地中海气候带中,欧亚大陆西部的地中海气候带的气候变化最大,每一季、每一年气候都有不同。这种气候变化有利于植物群中数量特别众多的一年生植物的演化。物种多和一年生植物多这两个因素结合起来,就意味着欧亚大陆西部的地中海气候带显然是一年生植物品种最繁多的地区。

The significance of that botanical wealth for humans is illustrated by the geographer Mark Blumler's studies of wild grass distributions. Among the world's thousands of wild grass species, Blumler tabulated the 56 with the largest seeds, the cream of nature's crop: the grass species with seeds at least 10 times heavier than the median grass species (see Table 8.1). Virtually all of them are native to Mediterranean zones or other seasonally dry environments. Furthermore, they are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Fertile Crescent or other parts of western Eurasia's Mediterranean zone, which offered a huge selection to incipient farmers: about 32 of the world's 56 prize wild grasses! Specifically, barley and emmer wheat, the two earliest important crops of the Fertile Crescent, rank respectively 3rd and 13th in seed size among those top 56. In contrast, the Mediterranean zone of Chile offered only two of those species. California and southern Africa just one each, and southwestern Australia none at all. That fact alone goes a long way toward explaining the course of human history.

关于这种植物财富对人类的意义,地理学家马克·布卢姆勒对野生禾本科植物分布的研究对此作出了说明。在世界上几千种野生禾本科植物中,布卢姆勒把其中种子最大的56种——自然的精华——列成表格:这些禾本科植物种子比中等的禾本科植物种子至少要重10倍(见表8.1)。几乎所有这些植物都是在地中海气候带或其他干旱环境中土生土长的。此外,它们又都以压倒优势集中在新月沃地和欧亚大陆西部地中海气候带的其他一些地区,从而使最初的农民有了巨大的选择余地:全世界56种最有价值的野生禾本科植物中的大约32种!特别是,在居首位的这56种作物中,新月沃地最早的两种作物大麦和二粒小麦在种子大小方面分别列第三位和第十三位。相比之下,智利的地中海型气候带只有两种,加利福尼亚和非洲南部各有一种,而澳大利亚西南部连一种都没有。仅仅这一事实就很有助于说明人类历史的进程。

| Area | Number of Species |

| West Asia, Europe, North Africa | 33 |

| Mediterranean zone | 32 |

| England | 1 |

| East Asia | 6 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 4 |

| Americas | 11 |

| North America | 4 |

| Mesoamerica | 5 |

| South America | 2 |

| Northern Australia | 2 |

| Total: | 56 |

TABLE 8.1 World Distribution of Large-Seeded Grass Species

表8.1大种子禾本科植物的世界分布

Table 12.1 of Mark Blumler's Ph.D. dissertation, “Seed Weight and Environment in Mediterranean-type Grasslands in California and Israel” (University of California, Berkeley, 1992), listed the world's 56 heaviest-seeded wild grass species (excluding bamboos) for which data were available. Grain weight in those species ranged from 10 milligrams to over 40 milligrams, about 10 times greater than the median value for all of the world's grass species. Those 56 species make up less than 1 percent of the world's grass species. This table shows that these prize grasses are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Mediterranean zone of western Eurasia.

马克·布卢姆勒的哲学博士论文《加利福尼亚和以色列的地中海型草场的种子重量和环境》(加利福尼亚大学伯克利分校,1992年)中的表12.1列出了有案可查的全世界56种种子最重的野生禾本科植物(不包括竹子)。这些植物的粒重从10毫克到40多毫克不等,比世界上所有禾本科植物的中值大10倍左右。这56种禾本科植物占全世界禾本科植物不到百分之一。本表表明,这些最有价值的禾本科植物以压倒优势集中在欧亚大陆西部的地中海气候带。

A third advantage of the Fertile Crescent's Mediterranean zone is that it provides a wide range of altitudes and topographies within a short distance. Its range of elevations, from the lowest spot on Earth (the Dead Sea) to mountains of 18,000 feet (near Teheran), ensures a corresponding variety of environments, hence a high diversity of the wild plants serving as potential ancestors of crops. Those mountains are in proximity to gentle lowlands with rivers, flood plains, and deserts suitable for irrigation agriculture. In contrast, the Mediterranean zones of southwestern Australia and, to a lesser degree, of South Africa and western Europe offer a narrower range of altitudes, habitats, and topographies.

新月沃地的地中海气候带的第三个有利条件,是它在短距离内高度和地形的富于变化。它的高度从地球上的最低点(死海)到18000英尺的高山(在德黑兰附近),应有尽有,从而保证了环境的相应变化,也因此而保证了可能成为作物的祖先的品种繁多的野生植物。这些高山的近傍是河流纵横的地势平缓的低地、泛滥平原和适于灌溉农业的沙漠。相比之下,澳大利亚西南部以及在较小程度上南非和欧洲西部的地中海型气候带,无论是高度、动植物栖息地还是地形都变化较少。

The range of altitudes in the Fertile Crescent meant staggered harvest seasons: plants at higher elevations produced seeds somewhat later than plants at lower elevations. As a result, hunter-gatherers could move up a mountainside harvesting grain seeds as they matured, instead of being overwhelmed by a concentrated harvest season at a single altitude, where all grains matured simultaneously. When cultivation began, it was a simple matter for the first farmers to take the seeds of wild cereals growing on hillsides and dependent on unpredictable rains, and to plant those seeds in the damp valley bottoms, where they would grow reliably and be less dependent on rain.

新月沃地的高度变化意味着可以把收获季节错开:高地植物结籽比低地植物多少要晚一些。因此,狩猎采集族群可以在谷物种子成熟时沿着山坡逐步向上去收获它们,而不是在一个高度上由于收获季节集中而无法应付,因为在那里所有谷物都是同时成熟的。作物栽培开始后,对最早的农民来说,采下野生谷物的种子,并把它们种在潮湿的谷底,是一件再容易不过的事。这些野生谷物本来都是长在山坡上,依赖不知何时才会来到的雨水,而把它们种在潮湿的谷底,它们就能可靠地生长,也不再那么依赖雨水了。

The Fertile Crescent's biological diversity over small distances contributed to a fourth advantage—its wealth in ancestors not only of valuable crops but also of domesticated big mammals. As we shall see, there were few or no wild mammal species suitable for domestication in the other Mediterranean zones of California, Chile, southwestern Australia, and South Africa. In contrast, four species of big mammals—the goat, sheep, pig, and cow—were domesticated very early in the Fertile Crescent, possibly earlier than any other animal except the dog anywhere else in the world. Those species remain today four of the world's five most important domesticated mammals (Chapter 9). But their wild ancestors were commonest in slightly different parts of the Fertile Crescent, with the result that the four species were domesticated in different places: sheep possibly in the central part, goats either in the eastern part at higher elevations (the Zagros Mountains of Iran) or in the southwestern part (the Levant), pigs in the north-central part, and cows in the western part, including Anatolia. Nevertheless, even though the areas of abundance of these four wild progenitors thus differed, all four lived in sufficiently close proximity that they were readily transferred after domestication from one part of the Fertile Crescent to another, and the whole region ended up with all four species.

新月沃地在很小距离内的生物多样性,帮助形成了第四个有利条件——那里不仅有大量的重要作物的野生祖先,而且也有大量的得到驯化的大型哺乳动物的野生祖先。我们将会看到,在其他一些地中海型气候带,如加利福尼亚、智利、澳大利亚西南部和南非,很少有或根本没有适于驯化的野生哺乳动物。相比之下,有4种大型哺乳动物——山羊、绵羊、猪和牛——很早就在新月沃地驯化了,可能比世界上其他任何地方除狗以外的其他任何动物都要早。这些动物今天仍然是世界上5种最重要的已驯化的哺乳动物中的4种(第九章)。但它们的野生祖先在新月沃地的一些大同小异的地区最为常见,但结果却是这4种动物在不同的地方驯化了:绵羊可能是在中部地区,山羊或者是在东部高地(伊朗的扎格罗斯山脉),或者是在西南部(黎凡特[1]),猪在中北部,牛在西部,包括安纳托利亚。然而,尽管这4种动物的野生祖先数量众多的地区是如此不同,但由于它们生活的地方相当靠近,所以一经驯化,它们就很容易地从新月沃地的一个地方转移到另一个地方,于是这整个地区最后就到处都有这4种动物了。

Agriculture was launched in the Fertile Crescent by the early domestication of eight crops, termed “founder crops” (because they founded agriculture in the region and possibly in the world). Those eight founders were the cereals emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, and barley; the pulses lentil, pea, chickpea, and bitter vetch; and the fiber crop flax. Of these eight, only two, flax and barley, range in the wild at all widely outside the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia. Two of the founders had very small ranges in the wild, chickpea being confined to southeastern Turkey and emmer wheat to the Fertile Crescent itself. Thus, agriculture could arise in the Fertile Crescent from domestication of locally available wild plants, without having to wait for the arrival of crops derived from wild plants domesticated elsewhere. Conversely, two of the eight founder crops could not have been domesticated anywhere in the world except in the Fertile Crescent, since they did not occur wild elsewhere.

新月沃地的农业开始于对所谓8大“始祖作物”的早期驯化(因为是这些作物开创了这一地区的、可能还有全世界的农业)。这8大始祖作物是谷类中的二粒小麦、单粒小麦和大麦;豆类中的兵豆、豌豆、鹰嘴豆和苦巢菜;以及纤维作物亚麻。在这8种作物中,只有亚麻和大麦这2种在新月沃地和安纳托利亚以外地区有广泛的野外分布。还有2种始祖作物只有很小的野外分布,一种是鹰嘴豆,只限于土耳其东南部,还有一种是二粒小麦,只限于新月沃地本身。因此,农业在新月沃地可以从驯化当地现成的野生植物开始,而不用等到引进在别处由驯化野生植物而得到的作物。相反,这8大始祖作物中有2种除新月沃地外不可能在世界上的任何地方得到驯化,因为它们在其他地方没有野生分布。

Thanks to this availability of suitable wild mammals and plants, early peoples of the Fertile Crescent could quickly assemble a potent and balanced biological package for intensive food production. That package comprised three cereals, as the main carbohydrate sources; four pulses, with 20–25 percent protein, and four domestic animals, as the main protein sources, supplemented by the generous protein content of wheat; and flax as a source of fiber and oil (termed linseed oil: flax seeds are about 40 percent oil). Eventually, thousands of years after the beginnings of animal domestication and food production, the animals also began to be used for milk, wool, plowing, and transport. Thus, the crops and animals of the Fertile Crescent's first farmers came to meet humanity's basic economic needs: carbohydrate, protein, fat, clothing, traction, and transport.

由于能够得到合适的野生哺乳动物和植物,新月沃地的先民们能够为集约型粮食生产迅速装配起一个有效而平衡的生物组合。这个组合包括作为碳水化合物主要来源的3种谷物,作为蛋白质主要来源的4种豆类(含蛋白质20%至25%)和4种家畜,再以小麦的丰富蛋白质为补充;以及作为纤维和油(叫做亚麻籽油:亚麻籽含有约40%的油)的一个来源的亚麻。最后,在动物驯化和粮食生产出现的几千年后,这些动物也开始被用来产奶和剪毛,并帮助人类犁田和运输。因此,新月沃地最早的农民的这些作物和牲畜开始满足人类的基本经济需要:碳水化合物、蛋白质、脂肪、衣着、牵引和运输。

A final advantage of early food production in the Fertile Crescent is that it may have faced less competition from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle than that in some other areas, including the western Mediterranean. Southwest Asia has few large rivers and only a short coastline, providing relatively meager aquatic resources (in the form of river and coastal fish and shellfish). One of the important mammal species hunted for meat, the gazelle, originally lived in huge herds but was overexploited by the growing human population and reduced to low numbers. Thus, the food production package quickly became superior to the hunter-gatherer package. Sedentary villages based on cereals were already in existence before the rise of food production and predisposed those hunter-gatherers to agriculture and herding. In the Fertile Crescent the transition from hunting-gathering to food production took place relatively fast: as late as 9000 B.C. people still had no crops and domestic animals and were entirely dependent on wild foods, but by 6000 B.C. some societies were almost completely dependent on crops and domestic animals.

新月沃地早期粮食生产的最后一个有利条件是:同包括西地中海沿岸在内的一些地区相比,那里所面临的来自狩猎采集生活方式的竞争可能要少一些。西南亚很少有大江大河,只有很短的海岸线,所以那里较少水产资源(如江河和近海鱼类及有壳水生动物)。在那里,为了肉食而被人猎杀的哺乳动物之一是瞪羚。瞪羚本来是群居动物,但因人口增加而被过度利用,数目已大大减少。因此,粮食生产的整个好处很快就超过了狩猎采集的整个好处。以谷物为基础的定居村庄在粮食生产前就已存在,并使那些狩猎采集族群容易接受农业和放牧生活。在新月沃地,从狩猎采集向粮食生产的转变是比较快的:迟至公元前9000年,人们还没有任何作物和家畜而完全依赖野生的食物,但到公元前6000年,有些社会已几乎完全依赖作物和家畜了。xxx

The situation in Mesoamerica contrasts strongly: that area provided only two domesticable animals (the turkey and the dog), whose meat yield was far lower than that of cows, sheep, goats, and pigs; and corn, Mesoamerica's staple grain, was, as I've already explained, difficult to domesticate and perhaps slow to develop. As a result, domestication may not have begun in Mesoamerica until around 3500 B.C. (the date remains very uncertain); those first developments were undertaken by people who were still nomadic hunter-gatherers; and settled villages did not arise there until around 1500 B.C.

中美洲的情况则与此形成了强烈的对比:那个地区只有两种可以驯化的动物(火鸡和狗),它们所提供的肉远远少于牛、绵羊、山羊和猪;而且我已解释过,中美洲的主要谷物玉米难以驯化,或许培育起来也很缓慢。因此,中美洲动植物的驯化可能直到公元前3500年左右才开始(这个年代仍然很不确定);这方面的最早发展应归功于仍然四处流浪的狩猎采集族群;而定居的村庄直到公元前1500年左右才宣告出现。

IN ALL THIS discussion of the Fertile Crescent's advantages for the early rise of food production, we have not had to invoke any supposed advantages of Fertile Crescent peoples themselves. Indeed, I am unaware of anyone's even seriously suggesting any supposed distinctive biological features of the region's peoples that might have contributed to the potency of its food production package. Instead, we have seen that the many distinctive features of the Fertile Crescent's climate, environment, wild plants, and animals together provide a convincing explanation.

在所有这些关于促使新月沃地很早出现粮食生产的诸多有利条件的讨论中,我一直不曾提出过任何想象中的关于新月沃地各族群本身所具有的有利条件。事实上,我不知道是否有人认真提出过那一地区的族群具有任何想象中的与众不同的生物学上的特点,以致竟会帮助实现了该地区粮食生产的巨大力量。相反,我倒是看到了新月沃地的气候、环境和野生动植物的许多与众不同的特点一起提供了一个令人信服的解释。

Since the food production packages arising indigenously in New Guinea and in the eastern United States were considerably less potent, might the explanation there lie with the peoples of those areas? Before turning to those regions, however, we must consider two related questions arising in regard to any area of the world where food production never developed independently or else resulted in a less potent package. First, do hunter-gatherers and incipient farmers really know well all locally available wild species and their uses, or might they have overlooked potential ancestors of valuable crops? Second, if they do know their local plants and animals, do they exploit that knowledge to domesticate the most useful available species, or do cultural factors keep them from doing so?

既然在新几内亚和美国东部当地发展起来的整个粮食生产的力量要小得多,那么解释也许与那些地区的族群有关?然而,在我们转而讨论那些地区之前,我们必须考虑一下两个相关的问题。世界上任何地区,只要那里不是独立发展出粮食生产,或者最后整个粮食生产的力量不是那么大,就都会产生这两个问题。第一个问题是:狩猎采集族群以及最早的农民真的十分了解当地现有的各种野生物种和它们的用途,或者他们可能忽略了一些主要作物的潜在祖先?第二个问题是:如果他们真的了解当地的动植物,那么他们是否利用这种知识来驯化现有的最有用的物种,或者是否有某些文化因素使他们没有能那样去做?

As regards the first question, an entire field of science, termed ethnobiology, studies peoples' knowledge of the wild plants and animals in their environment. Such studies have concentrated especially on the world's few surviving hunting-gathering peoples, and on farming peoples who still depend heavily on wild foods and natural products. The studies generally show that such peoples are walking encyclopedias of natural history, with individual names (in their local language) for as many as a thousand or more plant and animal species, and with detailed knowledge of those species' biological characteristics, distribution, and potential uses. As people become increasingly dependent on domesticated plants and animals, this traditional knowledge gradually loses its value and becomes lost, until one arrives at modern supermarket shoppers who could not distinguish a wild grass from a wild pulse.

关于第一个问题,有一门叫做人种生物学的学科专门研究人对其环境中的动植物的了解程度。这门学科的研究对象主要是世界上幸存的为数很少的狩猎采集族群以及仍然严重依赖野生食物和自然产品的农业部族。这些研究普遍表明,这些族群是博物学的活的百科全书,他们叫得出(用当地语言)多达1000种或更多的动植物的名称,他们对这些物种的生物学特点、地理分布和潜在用途具有详尽的知识。随着人们越来越依赖已经驯化的动植物,这种传统知识逐渐失去了价值,甚至已经失传,直到人们成了连野草和野豆也分不清的现代超市上的购物者。

Here's a typical example. For the last 33 years, while conducting biological exploration in New Guinea, I have been spending my field time there constantly in the company of New Guineans who still use wild plants and animals extensively. One day, when my companions of the Foré tribe and I were starving in the jungle because another tribe was blocking our return to our supply base, a Foré man returned to camp with a large rucksack full of mushrooms he had found, and started to roast them. Dinner at last! But then I had an unsettling thought: what if the mushrooms were poisonous?

这里有一个典型的例子。过去33年中,我在新几内亚进行生物调查,在野外度过我的时光,我的身边始终有一批仍然广泛利用野生动植物的新几内亚人陪伴着我。有一天,我和我的福雷部落的朋友在丛林中饿得发慌,因为另一个部落挡住了我们返回补给基地的路。这时,一个福雷部落的男子回到营地,带来了一个大帆布背包,里面装满了他找到的蘑菇。他开始烤起蘑菇来。终于可以大吃一顿了!但我在这时产生了一个令人不安的想法:如果这些蘑菇有毒,怎么办?

I patiently explained to my Foré companions that I had read about some mushrooms' being poisonous, that I had heard of even expert American mushroom collectors' dying because of the difficulty of distinguishing safe from dangerous mushrooms, and that although we were all hungry, it just wasn't worth the risk. At that point my companions got angry and told me to shut up and listen while they explained some things to me. After I had been quizzing them for years about names of hundreds of trees and birds, how could I insult them by assuming they didn't have names for different mushrooms? Only Americans could be so stupid as to confuse poisonous mushrooms with safe ones. They went on to lecture me about 29 types of edible mushroom species, each species' name in the Foré language, and where in the forest one should look for it. This one, the tánti, grew on trees, and it was delicious and perfectly edible.

我耐心地向我的福雷部落的朋友们解释说,我在书上读到过有些蘑菇是有毒的,我还听说过由于有毒蘑菇和无毒蘑菇难以区别,甚至美国的一些采集蘑菇的专家也因中毒而死,虽然我们大家都很饿,但完全不值得去冒这个险。这时,我的朋友们生气了,他们叫我闭嘴,好好听他们说。多少年来,我向他们查问了几百种树木和鸟类的名字,现在我怎么可以侮辱他们,认为他们连不同的蘑菇都不认识呢?只有美国人才会愚蠢到分不清有毒蘑菇和无毒蘑菇。他们接着给我上课,告诉我29种可以食用的蘑菇,每一种蘑菇在福雷语中的名字,以及森林里什么地方可以找到它。这一种蘑菇叫做坦蒂,是长在树上的,它鲜美可口,绝对可吃。

Whenever I have taken New Guineans with me to other parts of their island, they regularly talk about local plants and animals with other New Guineans whom they meet, and they gather potentially useful plants and bring them back to their home villages to try planting them. My experiences with New Guineans are paralleled by those of ethnobiologists studying traditional peoples elsewhere. However, all such peoples either practice at least some food production or are the partly acculturated last remnants of the world's former hunter-gatherer societies. Knowledge of wild species was presumably even more detailed before the rise of food production, when everyone on Earth still depended entirely on wild species for food. The first farmers were heirs to that knowledge, accumulated through tens of thousands of years of nature observation by biologically modern humans living in intimate dependence on the natural world. It therefore seems extremely unlikely that wild species of potential value would have escaped the notice of the first farmers.

每次我带着新几内亚人到岛上的其他地方时,他们总要和他们遇见的其他新几内亚人谈起当地的动植物,并把可能有用的植物采集下来,带回他们住的村子里试种。我与新几内亚人在一起时所获得的经验,比得上研究其他地方传统族群的人种生物学家的经验。然而,所有这些族群或是至少在从事某种粮食生产,或是成了世界上部分被同化了的以往狩猎采集社会的最后残余。在粮食生产出现前,关于野生物种的知识大概要丰富得多,因为那时地球上的每一个人仍然完全依靠食用野生物种为生。最早的农民继承了这方面的知识,这是生活在对自然界的密切依赖之中的生物学上的现代人类经过几万年对自然界的观察而积累起来的知识。因此,具有潜在价值的野生物种竟会逃过最早的农民的注意,这看来是极不可能的。

The other, related question is whether ancient hunter-gatherers and farmers similarly put their ethnobiological knowledge to good use in selecting wild plants to gather and eventually to cultivate. One test comes from an archaeological site at the edge of the Euphrates Valley in Syria, called Tell Abu Hureyra. Between 10,000 and 9000 B.C. the people living there may already have been residing year-round in villages, but they were still hunter-gatherers; crop cultivation began only in the succeeding millennium. The archaeologists Gordon Hillman, Susan Colledge, and David Harris retrieved large quantities of charred plant remains from the site, probably representing discarded garbage of wild plants gathered elsewhere and brought to the site by its residents. The scientists analyzed over 700 samples, each containing an average of over 500 identifiable seeds belonging to over 70 plant species. It turned out that the villagers were collecting a prodigious variety (157 species!) of plants identified by their charred seeds, not to mention other plants that cannot now be identified.

另一个相关的问题是:古代的狩猎采集族群以及农民在为了采集并最终栽培的目的而选择野生植物时,是否同样地很好利用了他们的人种生物学知识。一个可以用来验证的例子来自叙利亚境内幼发拉底河河谷边缘的一个叫做特勒阿布胡瑞拉的考古遗址。从公元前1万年到公元前9000年,生活在那里的人可能已终年定居在村庄里,但他们仍然以狩猎采集为生;作物栽培只是在接下来的1000年中才开始的。考古学家戈登·希尔曼、苏珊·科利奇和大卫·哈里斯从这个遗址找到了大量烧焦了的植物残烬,它们可能是遗址上的居民在别处采集后带回来又被抛弃的成堆无用的野生植物。这些科学家分析了700多个样本,每个样本平均含有属于70多种植物的500多颗可识别的种子。结果证明,村民们采集了种类繁多(157种!)的植物,这些都是从已烧焦的种子辨认出来的,更别提现在还无法确认的其他植物了。

Were those naive villagers collecting every type of seed plant that they found, bringing it home, poisoning themselves on most of the species, and nourishing themselves from only a few species? No, they were not so silly. While 157 species sounds like indiscriminate collecting, many more species growing wild in the vicinity were absent from the charred remains. The 157 selected species fall into three categories. Many of them have seeds that are nonpoisonous and immediately edible. Others, such as pulses and members of the mustard family, have toxic seeds, but the toxins are easily removed, leaving the seeds edible. A few seeds belong to species traditionally used as sources of dyes or medicine. The many wild species not represented among the 157 selected are ones that would have been useless or harmful to people, including all of the most toxic weed species in the environment.

是不是这些无知的村民把他们发现的每一种种子植物采集下来,带回家去,因吃了其中的大多数而中毒,而只靠吃很少几种来维持生存?不,他们不会那样愚蠢。虽然这157种植物听起来好像是不加区别地采集的结果,但还有更多的生长在附近野地里的植物没有在这些烧焦的残烬中发现。被选中的这157种植物分为3类。其中有许多植物,它们的种子没有毒,因而立即可吃。其他一些植物,如豆类和芥科植物,它们的种子有毒,但毒素很容易去掉,种子仍然可吃。有些种子属于传统上用作染料和药材来源的植物。不在被选中的这157种中的许多野生植物,有的可能没有什么用处,有的可能对人有害,其中也包括当地生长的毒性最强的一些野草。

Thus, the hunter-gatherers of Tell Abu Hureyra were not wasting time and endangering themselves by collecting wild plants indiscriminately. Instead, they evidently knew the local wild plants as intimately as do modern New Guineans, and they used that knowledge to select and bring home only the most useful available seed plants. But those gathered seeds would have constituted the material for the unconscious first steps of plant domestication.

因此,特勒阿布胡瑞拉的狩猎采集族群并没有把时间浪费在不加区别地去采集可能危及自己生命的野生植物。相反,他们同现代的新几内亚人一样,显然对当地的野生植物有深刻的了解,所以他们就利用这种知识只去选择现有的最有用的种子植物并把它们带回家。但是,这些被收集来的种子竟构成了促使植物驯化迈出无意识的第一步的材料。

My other example of how ancient peoples apparently used their ethnobiological knowledge to good effect comes from the Jordan Valley in the ninth millennium B.C., the period of the earliest crop cultivation there. The valley's first domesticated cereals were barley and emmer wheat, which are still among the world's most productive crops today. But, as at Tell Abu Hureyra, hundreds of other seed-bearing wild plant species must have grown in the vicinity, and a hundred or more of them would have been edible and gathered before the rise of plant domestication. What was it about barley and emmer wheat that caused them to be the first crops? Were those first Jordan Valley farmers botanical ignoramuses who didn't know what they were doing? Or were barley and emmer wheat actually the best of the local wild cereals that they could have selected?

关于古代族群如何明显地充分利用他们的人种生物学知识这个问题,我的另一个例子来自公元前9000年的约旦河谷,最早的作物栽培就是在这一时期在那里开始的。约旦河谷最早驯化的谷物是大麦和二粒小麦,它们在今天仍是世界上最高产的作物。但和在特勒阿布胡瑞拉一样,另外数百种结籽的野生植物必定就生长在这附近,其中100种或更多可能是可以食用的,因此在植物驯化出现前就已被人采集。对于大麦和二粒小麦,是什么使它们成为最早的作物?约旦河谷的那些最早的农民难道对植物学一窍不通,竟然不知道自己在干什么?或者,难道大麦和二粒小麦竟是他们所能选择的当地最好的野生谷物?

Two Israeli scientists, Ofer Bar-Yosef and Mordechai Kislev, tackled this question by examining the wild grass species still growing wild in the valley today. Leaving aside species with small or unpalatable seeds, they picked out 23 of the most palatable and largest-seeded wild grasses. Not surprisingly, barley and emmer wheat were on that list.

有两个以色列科学家奥弗·巴尔-约瑟夫和莫迪凯·基斯列夫通过研究今天仍在约旦河谷生长的野生禾本科植物来着手解决这个问题。他们舍弃了那些种子小或种子不好吃的品种,挑选出23种种子最好吃的也是最大的野生禾本科植物。大麦和二粒小麦在被选之列,这是毫不奇怪的。

But it wasn't true that the 21 other candidates would have been equally useful. Among those 23, barley and emmer wheat proved to be the best by many criteria. Emmer wheat has the biggest seeds and barley the second biggest. In the wild, barley is one of the 4 most abundant of the 23 species, while emmer wheat is of medium abundance. Barley has the further advantage that its genetics and morphology permit it to evolve quickly the useful changes in seed dispersal and germination inhibition that we discussed in the preceding chapter. Emmer wheat, however, has compensating virtues: it can be gathered more efficiently than barley, and it is unusual among cereals in that its seeds do not adhere to husks. As for the other 21 species, their drawbacks include smaller seeds, in many cases lower abundance, and in some cases their being perennial rather than annual plants, with the consequence that they would have evolved only slowly under domestication.

但如认为其他21种候补的禾本科植物可能同样有用,那是不正确的。在那23种禾本科植物中,大麦和二粒小麦从许多标准看都是最好的。二粒小麦的种子最大,大麦的种子次大。在野生状态中,大麦是23种中产量最高的4种之一,二粒小麦的产量属于中等。大麦还有一个优点:它的遗传性和形态使它能够迅速形成我们在前一章所讨论的种子传播和发芽抑制方面的变化。然而,二粒小麦也有补偿性的优点:它比大麦容易采集,而且它还有一个不同于其他谷物的独特之处,因为它的种子容易和外壳分离。至于其他21种禾本科植物的缺点包括:种子较小,在许多情况下产量较低,在有些情况下它们是多年生植物,而不是一年生植物,结果它们在驯化过程中的演化反而会变得很慢。

Thus, the first farmers in the Jordan Valley selected the 2 very best of the 23 best wild grass species available to them. Of course, the evolutionary changes (following cultivation) in seed dispersal and germination inhibition would have been unforeseen consequences of what those first farmers were doing. But their initial selection of barley and emmer wheat rather than other cereals to collect, bring home, and cultivate would have been conscious and based on the easily detected criteria of seed size, palatability, and abundance.

因此,约旦河谷最早的农民从他们能够得到的23种最好的野生禾本科植物中选择了这两种最好的。当然,在栽培之后产生的演化,如种子传播和发芽抑制方面的改变,可能是这些最早的农民的所作所为的意想不到的结果。但是,他们在把谷物采集下来带回家去栽培时,一开始就选择了大麦和二粒小麦而不是其他谷物,这可能是有意识的行动,是以种子大小、好吃和产量高这些容易发现的标准为基础的。

This example from the Jordan Valley, like that from Tell Abu Hureyra, illustrates that the first farmers used their detailed knowledge of local species to their own benefit. Knowing far more about local plants than all but a handful of modern professional botanists, they would hardly have failed to cultivate any useful wild plant species that was comparably suitable for domestication.

约旦河谷的这个例子同特勒阿布胡瑞拉的例子一样,说明最早的农民为了自己的利益利用了他们对当地植物的丰富知识。除了少数几个现代的专业植物学家外,他们对当地植物的了解远远超过了其他所有的人,因此他们几乎不可能不去培育任何有用的比较适合驯化的野生植物。

WE CAN NOW examine what local farmers, in two parts of the world (New Guinea and the eastern United States) with indigenous but apparently deficient food production systems compared to that of the Fertile Crescent, actually did when more-productive crops arrived from elsewhere. If it turned out that such crops did not become adopted for cultural or other reasons, we would be left with a nagging doubt. Despite all our reasoning so far, we would still have to suspect that the local wild flora harbored some ancestor of a potential valuable crop that local farmers failed to exploit because of similar cultural factors. These two examples will also demonstrate in detail a fact critical to history: that indigenous crops from different parts of the globe were not equally productive.

同新月沃地的粮食生产相比,世界上有两个地方(新几内亚和美国东部)虽然也有本地的粮食生产系统,但显然是有缺陷的。现在我们可以来考察一下,当更多产的作物从别处引进这两个地方后,当地的农民究竟在做些什么。如果结果证明没有采纳这些作物是由于文化原因或其他原因,那么我们就会产生无法摆脱的怀疑。尽管我们迄今进行了各种各样的推理,我们可能仍然不得不怀疑,在当地的野生植物群中隐藏着一种潜在的重要作物的真正祖先,只是由于同样的文化因素,当地农民未能加以利用罢了。这两个例子同样会详细地说明一个对历史至关重要的事实:地球上不同地区的当地作物并不是同样多产的。

New Guinea, the largest island in the world after Greenland, lies just north of Australia and near the equator. Because of its tropical location and great diversity in topography and habitats, New Guinea is rich in both plant and animal species, though less so than continental tropical areas because it is an island. People have been living in New Guinea for at least 40,000 years—much longer than in the Americas, and slightly longer than anatomically modern peoples have been living in western Europe. Thus, New Guineans have had ample opportunity to get to know their local flora and fauna. Were they motivated to apply this knowledge to developing food production?

新几内亚是仅次于格陵兰的世界第二大岛,它在澳大利亚北面,靠近赤道。由于地处热带,加上十分多样化的地形和生境,新几内亚的动植物品种非常丰富,虽然在这方面它因是一个海岛,比起大陆热带地区来有所不及。人类在新几内亚至少已生活了4万年之久——比在美洲长得多,比解剖学上的现代人类在欧洲西部生活的时间也稍长一些。因此,新几内亚人有充分的机会去了解当地的植物群和动物群。他们是否积极地把这种知识用来发展粮食生产呢?

I mentioned already that the adoption of food production involved a competition between the food producing and the hunting-gathering lifestyles. Hunting-gathering is not so rewarding in New Guinea as to remove the motivation to develop food production. In particular, modern New Guinea hunters suffer from the crippling disadvantage of a dearth of wild game: there is no native land animal larger than a 100-pound flightless bird (the cassowary) and a 50-pound kangaroo. Lowland New Guineans on the coast do obtain much fish and shellfish, and some lowlanders in the interior still live today as hunter-gatherers, subsisting especially on wild sago palms. But no peoples still live as hunter-gatherers in the New Guinea highlands; all modern highlanders are instead farmers who use wild foods only to supplement their diets. When highlanders go into the forest on hunting trips, they take along garden-grown vegetables to feed themselves. If they have the misfortune to run out of those provisions, even they starve to death despite their detailed knowledge of locally available wild foods. Since the hunting-gathering lifestyle is thus nonviable in much of modern New Guinea, it comes as no surprise that all New Guinea highlanders and most lowlanders today are settled farmers with sophisticated systems of food production. Extensive, formerly forested areas of the highlands were converted by traditional New Guinea farmers to fenced, drained, intensively managed field systems supporting dense human populations.

我已经提到,采纳粮食生产涉及粮食生产的生活方式与狩猎采集的生活方式之间的竞争。在新几内亚,狩猎采集的回报还没有丰厚到可以打消发展粮食生产的积极性。尤其是,现代新几内亚的猎人由于野生猎物的不足而处于受到严重损害的不利地位:除了100磅重的不会飞的鸟(鹤鸵)和50磅重的袋鼠外,没有更大的本土陆地动物。沿海低地的新几内亚人的确获得了大量的鱼和有壳水生动物,而内地的有些低地人今天仍然过着狩猎采集生活,尤其要靠西谷椰子维持生存。但在新几内亚高原地区,没有任何居民仍然过着狩猎采集生活;相反,所有现代高原居民都是农民,他们只是为了补充日常饮食才利用野生食物。当高原居民进入森林去打猎时,他们带去路上吃的是园子里种的蔬菜。如果他们不幸断了粮,他们甚至会饿死,尽管他们熟知当地可以得到野生食物。既然狩猎采集的生活方式在现代新几内亚的很大一部分地区是这样地行不通,那么今天新几内亚所有的高原居民和大多数低地居民成了具有复杂的粮食生产系统的定居农民,这就没有什么奇怪的了。广阔的、昔日覆盖着森林的高原地区,被传统的新几内亚农民改造成围上了篱笆、修建起排水系统、精耕细作的、能够养活稠密人口的农田系统。

Archaeological evidence shows that the origins of New Guinea agriculture are ancient, dating to around 7000 B.C. At those early dates all the landmasses surrounding New Guinea were still occupied exclusively by hunter-gatherers, so this ancient agriculture must have developed independently in New Guinea. While unequivocal remains of crops have not been recovered from those early fields, they are likely to have included some of the same crops that were being grown in New Guinea at the time of European colonization and that are now known to have been domesticated locally from wild New Guinea ancestors. Foremost among these local domesticates is the modern world's leading crop, sugarcane, of which the annual tonnage produced today nearly equals that of the number two and number three crops combined (wheat and corn). Other crops of undoubted New Guinea origin are a group of bananas known as Australimusa bananas, the nut tree Canarium indicum, and giant swamp taro, as well as various edible grass stems, roots, and green vegetables. The breadfruit tree and the root crops yams and (ordinary) taro may also be New Guinean domesticates, although that conclusion remains uncertain because their wild ancestors are not confined to New Guinea but are distributed from New Guinea to Southeast Asia. At present we lack evidence that could resolve the question whether they were domesticated in Southeast Asia, as traditionally assumed, or independently or even only in New Guinea.

考古学的证据表明,新几内亚农业起源很早,约公元前7000年。在这早期年代里,新几内亚周围的所有陆块仍然只有狩猎采集族群居住,因此这一古老的农业必定是在新几内亚独立发展起来的。虽然从这些早期农田里还没有发现明确的作物残骸,但其中可能包含了欧洲人殖民时期在新几内亚种植的那几种作物,而且现在已经知道,这些作物都是从它们的新几内亚野生祖先在当地驯化出来的。在本地驯化的这些植物中位居最前列的是现代世界的主要作物甘蔗。今天甘蔗年产量的总吨数几乎等于第二号作物和第三号作物(小麦和玉米)产量的总和。其他一些肯定原产新几内亚的作物是香蕉、坚果树、巨大的沼泽芋以及各种各样可吃的草茎、根和绿叶蔬菜。面包果树和根用作物薯蓣及(普通)芋艿可能也是在新几内亚驯化的,虽然这种结论仍然不能确定,因为它们的野生祖先并不限于新几内亚,而是从新几内亚到西南亚都有分布。至于它们究竟像传统所认为的那样是在西南亚驯化的,还是在新几内亚或甚至只是在新几内亚独立驯化的,目前我们还缺乏能够解决这个问题的证据。

However, it turns out that New Guinea's biota suffered from three severe limitations. First, no cereal crops were domesticated in New Guinea, whereas several vitally important ones were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, Sahel, and China. In its emphasis instead on root and tree crops, New Guinea carries to an extreme a trend seen in agricultural systems in other wet tropical areas (the Amazon, tropical West Africa, and Southeast Asia), whose farmers also emphasized root crops but did manage to come up with at least two cereals (Asian rice and a giant-seeded Asian cereal called Job's tears). A likely reason for the failure of cereal agriculture to arise in New Guinea is a glaring deficiency of the wild starting material: not one of the world's 56 largest-seeded wild grasses is native there.

然而,结果证明,新几内亚的生物区系受到3个方面的严重限制。首先,在新几内亚没有任何驯化的谷类作物,而在新月沃地、萨赫勒地带和中国都有几种极其重要的谷类作物。新几内亚重视根用作物和树生作物,但它却把我们在其他湿润的热带地区(亚马孙河流域、热带西非和东南亚)的农业体系中所看到的一种倾向推向极端,因为那些地区的农民虽也重视根用作物,但却设法培育了至少两种谷物(亚洲稻米和一种叫做薏的大籽粒亚洲谷物)。新几内亚未能出现谷物农业的一个可能的原因,是那里的野生起始物种具有一种引人注目的缺点:世界上56种种子最大的野生禾本科植物没有一种是生长在那里的。

Second, the New Guinea fauna included no domesticable large mammal species whatsoever. The sole domestic animals of modern New Guinea, the pig and chicken and dog, arrived from Southeast Asia by way of Indonesia within the last several thousand years. As a result, while New Guinea lowlanders obtain protein from the fish they catch, New Guinea highland farmer populations suffer from severe protein limitation, because the staple crops that provide most of their calories (taro and sweet potato) are low in protein. Taro, for example, consists of barely 1 percent protein, much worse than even white rice, and far below the levels of the Fertile Crescent's wheats and pulses (8–14 percent and 20–25 percent protein, respectively).

其次,新几内亚的动物群中没有任何可以驯化的大型哺乳动物。现代新几内亚驯养的动物只有猪、鸡和狗,它们也都是在过去几千年中经由印度尼西亚从东南亚引进的。因此,虽然新几内亚的低地居民从他们捕捉到的鱼类获得了蛋白质,但新几内亚的高原地区的居民在获得蛋白质方面受到严重的限制,因为给他们提供大部分卡路里的主要作物(芋艿和甘薯)的蛋白质含量很低。例如,芋艿的蛋白质含量几乎不到1%,甚至比白米差得多,更远在新月沃地的小麦和豆类(蛋白质含量分别为8%-14%和20%-25%)之下。

Children in the New Guinea highlands have the swollen bellies characteristic of a high-bulk but protein-deficient diet. New Guineans old and young routinely eat mice, spiders, frogs, and other small animals that peoples elsewhere with access to large domestic mammals or large wild game species do not bother to eat. Protein starvation is probably also the ultimate reason why cannibalism was widespread in traditional New Guinea highland societies.

新几内亚高原地区的儿童患有膨胀病,这是饮食量多但蛋白质缺乏所引起的典型的疾病。新几内亚人无分老幼,常常吃老鼠、蜘蛛、青蛙和其他小动物,而在别的地方,由于能够得到大型家畜或大型野生猎物,人们对那些东西是不屑一顾的。蛋白质缺乏可能也是新几内亚高原社会流行吃人肉的根本原因。

Finally, in former times New Guinea's available root crops were limiting for calories as well as for protein, because they do not grow well at the high elevations where many New Guineans live today. Many centuries ago, however, a new root crop of ultimately South American origin, the sweet potato, reached New Guinea, probably by way of the Philippines, where it had been introduced by Spaniards. Compared with taro and other presumably older New Guinea root crops, the sweet potato can be grown up to higher elevations, grows more quickly, and gives higher yields per acre cultivated and per hour of labor. The result of the sweet potato's arrival was a highland population explosion. That is, even though people had been farming in the New Guinea highlands for many thousands of years before sweet potatoes were introduced, the available local crops had limited them in the population densities they could attain, and in the elevations they could occupy.

最后,以往新几内亚能够得到的根用作物不但蛋白质少,而且卡路里也不高,因为这些作物在如今生活着许多新几内亚人的高地上生长不好。然而,许多世纪前,一种原产于南美洲的新的根用作物传到了新几内亚,它先由西班牙人引进菲律宾,后来大概再由菲律宾传到新几内亚的。同芋艿和其他可能历史更悠久的根用作物相比,甘薯能够在地势更高的地方生长,长得更快,按每英亩耕地和每小时所花的劳力计算,产量也更高。甘薯引进的结果是高原人口激增。就是说,虽然在甘薯引进前人们在新几内亚高原地区从事农业已有数千年之久,但当地现有的作物一直在他们能够居住的高原地区使他们能够达到的人口密度受到了限制。

In short, New Guinea offers an instructive contrast to the Fertile Crescent. Like hunter-gatherers of the Fertile Crescent, those of New Guinea did evolve food production independently. However, their indigenous food production was restricted by the local absence of domesticable cereals, pulses, and animals, by the resulting protein deficiency in the highlands, and by limitations of the locally available root crops at high elevations. Yet New Guineans themselves know as much about the wild plants and animals available to them as any peoples on Earth today. They can be expected to have discovered and tested any wild plant species worth domesticating. They are perfectly capable of recognizing useful additions to their crop larder, as is shown by their exuberant adoption of the sweet potato when it arrived. That same lesson is being driven home again in New Guinea today, as those tribes with preferential access to introduced new crops and livestock (or with the cultural willingness to adopt them) expand at the expense of tribes without that access or willingness. Thus, the limits on indigenous food production in New Guinea had nothing to do with New Guinea peoples, and everything with the New Guinea biota and environment.

总之,新几内亚提供了一个和新月沃地截然不同的富于启发性的对比。同新月沃地的狩猎采集族群一样,新几内亚的狩猎采集族群也是独立地逐步形成粮食生产的。然而,由于当地没有可以驯化的谷物、豆类植物和动物,由于因此而带来的高原地区蛋白质的缺乏,同时也由于高原地区当地现有根用作物的局限,他们的土生土长的粮食生产受到了限制。不过,新几内亚人对他们现有的野生动植物的了解,一点也不比今天地球上的任何民族差。他们同样能够发现并检验任何值得驯化的野生植物。他们完全能够认出在他们现有的作物之外的其他一些有用的作物,他们在甘薯引进时兴高采烈地接受了它就是证明。今天,这个教训在新几内亚正在又一次被人们所接受,因为那些具有优先获得引进的新作物和新牲畜的机会(或具有采纳它们的文化意愿)的部落发展壮大了自己,而受到损害的则是那些没有这种机会或意愿的部落。因此,新几内亚土生土长的粮食生产所受到的限制与新几内亚的族群没有任何关系,而是与新几内亚的生物区系和环境有着最密切的关系。

OUR OTHER EXAMPLE of indigenous agriculture apparently constrained by the local flora comes from the eastern United States. Like New Guinea, that area supported independent domestication of local wild plants. However, early developments are much better understood for the eastern United States than for New Guinea: the crops grown by the earliest farmers have been identified, and the dates and crop sequences of local domestication are known. Well before other crops began to arrive from elsewhere, Native Americans settled in eastern U.S. river valleys and developed intensified food production based on local crops. Hence they were in a position to take advantage of the most promising wild plants. Which ones did they actually cultivate, and how did the resulting local crop package compare with the Fertile Crescent's founder package?

关于本地农业显然受到当地植物群的限制这个问题,我们的另一个例子来自美国东部。同新几内亚一样,那个地区也为独立驯化当地的野生植物提供了条件。然而,人们对美国东部早期发展的了解,要比对新几内亚早期发展的了解多得多:美国东部最早的农民所种植的作物已经得到确认,当地植物驯化的年代和作物序列也已为人们所知。在其他作物开始从别处引进之前很久,美洲土著便已在美国东部的河谷地区定居下来,并在当地作物的基础上发展了集约型的粮食生产。因此,他们有能力去利用那些最有希望的野生植物。他们实际上栽培了哪些野生植物,以及怎样把由此而产生的当地一系列作物去和新月沃地的一系列始祖作物作一比较呢?

It turns out that the eastern U.S. founder crops were four plants domesticated in the period 2500–1500 B.C., a full 6,000 years after wheat and barley domestication in the Fertile Crescent. A local species of squash provided small containers, as well as yielding edible seeds. The remaining three founders were grown solely for their edible seeds (sunflower, a daisy relative called sumpweed, and a distant relative of spinach called goosefoot).

原来美国东部的始祖作物是4种植物,它们在公元前2500年至1500年这一时期得到驯化,比新月沃地的小麦和大麦的驯化时间晚了整整6000年。当地的一种南瓜属植物不但能产生可吃的种子,而且还可用作小型容器。其余3种始祖作物完全是因为它们的可吃的种子才被人栽种的(向日葵、一种叫做菊草的雏菊亲缘植物和一种叫做藜的菠菜远亲植物)。

But four seed crops and a container fall far short of a complete food production package. For 2,000 years those founder crops served only as minor dietary supplements while eastern U.S. Native Americans continued to depend mainly on wild foods, especially wild mammals and waterbirds, fish, shellfish, and nuts. Farming did not supply a major part of their diet until the period 500–200 B.C., after three more seed crops (knotweed, maygrass, and little barley) had been brought into cultivation.

但4种种子作物和一种容器远远够不上完全的粮食生产组合。这些始祖作物在2万年中不过是饮食的小小补充,美国东部的印第安人仍然主要地依赖野生食物,尤其是野生的哺乳动物和水鸟、鱼、有壳水生动物和坚果。直到公元前500年至200年这一时期,在又有3种种子作物(萹蓄、五月草和小大麦)得到栽培之后,农业才成为他们食品的主要部分的来源。

A modern nutritionist would have applauded those seven eastern U.S.crops. All of them were high in protein—17–32 percent, compared with 8–14 percent for wheat, 9 percent for corn, and even lower for barley and white rice. Two of them, sunflower and sumpweed, were also high in oil (45–47 percent). Sumpweed, in particular, would have been a nutritionist's ultimate dream, being 32 percent protein and 45 percent oil. Why aren't we still eating those dream foods today?

现代的营养学家可能会对美国东部的这7种作物大加赞赏。它们的蛋白质含量都很高——达17%-33%,而小麦是8%-14%,玉米是9%,大麦和白米甚至更低。其中两种——向日葵和菊草含油量也很高(45%-47%)。尤其是菊草,由于含有32%的蛋白质和45%的油,可能成为营养学家梦寐以求的最佳作物。我们今天为什么仍然没有吃上这些理想的粮食呢?

Alas, despite their nutritional advantage, most of these eastern U.S. crops suffered from serious disadvantages in other respects. Goosefoot, knotweed, little barley, and maygrass had tiny seeds, with volumes only one-tenth that of wheat and barley seeds. Worse yet, sumpweed is a wind-pollinated relative of ragweed, the notorious hayfever-causing plant. Like ragweed's, sumpweed's pollen can cause hayfever where the plant occurs in abundant stands. If that doesn't kill your enthusiasm for becoming a sumpweed farmer, be aware that it has a strong odor objectionable to some people and that handling it can cause skin irritation.

唉,美国东部的这些作物的大多数虽然在营养方面有其优点,但它们在其他方面也存在严重的缺点。藜属植物、萹蓄、小大麦和五月草的种子很小,体积只有小麦和大麦种子的十分之一。更糟的是,菊草是靠风媒传粉的豚草的亲缘植物,而豚草是众所周知的引起花粉病的植物。同豚草的花粉一样,凡是在菊草长得茂盛的地方,菊草的花粉都会引起花粉病。如果这一点还不能使你想要做一个种植菊草的农民的热情完全消失的话,那就请你注意它有一种令某些人讨厌的强烈气味,而且接触到它会引起皮肤过敏。

Mexican crops finally began to reach the eastern United States by trade routes after A.D. 1. Corn arrived around A.D. 200, but its role remained very minor for many centuries. Finally, around A.D. 900 a new variety of corn adapted to North America's short summers appeared, and the arrival of beans around A.D. 1100 completed Mexico's crop trinity of corn, beans, and squash. Eastern U.S. farming became greatly intensified, and densely populated chiefdoms developed along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. In some areas the original local domesticates were retained alongside the far more productive Mexican trinity, but in other areas the trinity replaced them completely. No European ever saw sumpweed growing in Indian gardens, because it had disappeared as a crop by the time that European colonization of the Americas began, in A.D. 1492. Among all those ancient eastern U.S. crop specialties, only two (sunflower and eastern squash) have been able to compete with crops domesticated elsewhere and are still grown today. Our modern acorn squashes and summer squashes are derived from those American squashes domesticated thousands of years ago.

公元元年后,墨西哥的一些作物最后经由贸易路线开始到达美国东部。玉米是在公元200年左右引进的,但在许多世纪中,它所起的作用始终较小。最后,在公元900年左右,一个适应北美洲短暂夏季的新品种的玉米出现了,而在公元1100年左右随着豆类的引进,墨西哥的玉米、豆类和南瓜类这三位一体的作物便齐全了。美国东部的农业大大地集约化了,人口稠密的酋长管辖的部落沿密西西比河及其支流发展了起来。在某些地区,原来在当地驯化的作物同远为多产的墨西哥三位一体的作物一起保留了下来,但在另一些地区,这三位一体的作物则完全取代了它们。没有一个欧洲人见到过生长在印第安人园子里的菊草,因为到欧洲人于公元1492年开始在美洲殖民时,菊草作为一种作物已经消失了。在美国东部所有这些古代特有作物中,只有2种(向日葵和东部南瓜)能够同在其他地方驯化的作物相媲美,并且至今仍在种植。我们现代的橡实形南瓜和密生西葫芦就是从几千年前驯化的美洲南瓜属植物演化而来的。

Thus, like the case of New Guinea, that of the eastern United States is instructive. A priori, the region might have seemed a likely one to support productive indigenous agriculture. It has rich soils, reliable moderate rainfall, and a suitable climate that sustains bountiful agriculture today. The flora is a species-rich one that includes productive wild nut trees (oak and hickory). Local Native Americans did develop an agriculture based on local domesticates, did thereby support themselves in villages, and even developed a cultural florescence (the Hopewell culture centered on what is today Ohio) around 200 B.C.-A.D. 400. They were thus in a position for several thousand years to exploit as potential crops the most useful available wild plants, whatever those should be.

因此,像新几内亚的情形一样,美国东部的情形也是富于启发性的。从假定出发,这个地区看来可能具有促进当地多产农业的条件。它有肥沃的土壤,可靠而适中的雨量,以及保持今天丰产农业的合适的气候。该地的植物群品种繁多,包括多产的野生坚果树(橡树和山核桃树)。当地的印第安人发展了以当地驯化植物为基础的农业,从而在村庄里过着自给自足的定居生活,他们甚至在公元前200年至公元400年期间带来了文化的繁荣(以今天俄亥俄州为中心的霍普韦尔文化)。这样,他们在几千年中就能够把最有用的可以得到的任何野生植物当作潜在的作物来加以利用。

Nevertheless, the Hopewell florescence sprang up nearly 9,000 years after the rise of village living in the Fertile Crescent. Still, it was not until after A.D. 900 that the assembly of the Mexican crop trinity triggered a larger population boom, the so-called Mississippian florescence, which produced the largest towns and most complex societies achieved by Native Americans north of Mexico. But that boom came much too late to prepare Native Americans of the United States for the impending disaster of European colonization. Food production based on eastern U.S. crops alone had been insufficient to trigger the boom, for reasons that are easy to specify. The area's available wild cereals were not nearly as useful as wheat and barley. Native Americans of the eastern United States domesticated no locally available wild pulse, no fiber crop, no fruit or nut tree. They had no domesticated animals at all except for dogs, which were probably domesticated elsewhere in the Americas.

尽管如此,霍普韦尔文化繁荣的出现,还是比新月沃地乡村生活的出现晚了差不多9000年。不过,直到公元900年之后,墨西哥三位一体的作物组合才引发了人口的较大增长,即所谓的密西西比文化的繁荣。人口的增长使墨西哥以北的印第安人得以建设最大的城镇和最复杂的社会。但这种人口的增长毕竟来得太晚,没有能使美国的印第安人为迫在眉睫的欧洲人殖民灾难作好准备。仅仅以美国东部的作物为基础的粮食生产,还不足以引发人口的增长,这原因是不难说明的。这一地区现有的野生谷物,远远不如小麦和大麦那样有用。美国东部的印第安人没有驯化过任何可在当地得到的豆类、纤维作物、水果树或坚果树。除了狗,他们没有任何家畜,而狗大概也是在美洲的其他地方驯化的。

It's also clear that Native Americans of the eastern United States were not overlooking potential major crops among the wild species around them. Even 20th-century plant breeders, armed with all the power of modern science, have had little success in exploiting North American wild plants. Yes, we have now domesticated pecans as a nut tree and blueberries as a fruit, and we have improved some Eurasian fruit crops (apples, plums, grapes, raspberries, blackberries, strawberries) by hybridizing them with North American wild relatives. However, those few successes have changed our food habits far less than Mexican corn changed food habits of Native Americans in the eastern United States after A.D. 900.

有一点也是很清楚的:美国东部的印第安人对他们周围的野生植物中潜在的主要作物并未视而不见。即使是用现代科学知识武装起来的20世纪植物育种专家,在利用北美的野生植物方面也很少取得成功。诚然,我们现在已把美洲山核桃驯化成一种坚果树并把乌饭树的蓝色浆果驯化成一种水果,而且我们也已把欧亚大陆的一些水果作物(苹果、李、葡萄、树莓、黑刺莓、草莓)同北美的野生亲缘植物进行杂交来改良品种。然而,这几项成就对我们饮食习惯的改变,远远不及公元900年后墨西哥的玉米对美国东部印第安人饮食习惯的改变那样深刻。

The farmers most knowledgeable about eastern U.S. domesticates, the region's Native Americans themselves, passed judgment on them by discarding or deemphasizing them when the Mexican trinity arrived. That outcome also demonstrates that Native Americans were not constrained by cultural conservativism and were quite able to appreciate a good plant when they saw it. Thus, as in New Guinea, the limitations on indigenous food production in the eastern United States were not due to Native American peoples themselves, but instead depended entirely on the American biota and environment.

对美国东部驯化植物最了解的农民,就是这个地区的印第安人自己。他们在墨西哥三位一体的作物引进后宣判了当地驯化植物的命运:或者把它们完全抛弃,或者把它们的重要性降低。这个结果也表明了印第安人没有受到文化保守主义的束缚,而是在看到一种优良的植物时完全能够认识到它的价值。因此,同在新几内亚一样,美国东部土生土长的粮食生产所受到的限制,不是由于印第安人本身,而是完全决定于美洲的生物区系和环境。

WE HAVE NOW considered examples of three contrasting areas, in all of which food production did arise indigenously. The Fertile Crescent lies at one extreme; New Guinea and the eastern United States lie at the opposite extreme. Peoples of the Fertile Crescent domesticated local plants much earlier. They domesticated far more species, domesticated far more productive or valuable species, domesticated a much wider range of types of crops, developed intensified food production and dense human populations more rapidly, and as a result entered the modern world with more advanced technology, more complex political organization, and more epidemic diseases with which to infect other peoples.

现在,我们已经考虑了3个对照地区的例子,在这3个例子中,粮食生产都是土生土长的。新月沃地处于一个极端;新几内亚和美国东部处于另一个极端。新月沃地的族群对当地植物的驯化在时间上要早得多。他们驯化了多得多的植物品种,驯化了产量多得多或价值大得多的植物品种,驯化了范围广泛得多的各种类型的作物,更快地发展了集约型粮食生产和稠密的人口,因此,他们是带着更先进的技术、更复杂的行政组织和用以传染其他族群的更流行的疾病进入现代世界的。

We found that these differences between the Fertile Crescent, New Guinea, and the eastern United States followed straightforwardly from the differing suites of wild plant and animal species available for domestication, not from limitations of the peoples themselves. When more-productive crops arrived from elsewhere (the sweet potato in New Guinea, the Mexican trinity in the eastern United States), local peoples promptly took advantage of them, intensified food production, and increased greatly in population. By extension, I suggest that areas of the globe where food production never developed indigenously at all—California, Australia, the Argentine pampas, western Europe, and so on—may have offered even less in the way of wild plants and animals suitable for domestication than did New Guinea and the eastern United States, where at least a limited food production did arise. Indeed, Mark Blumler's worldwide survey of locally available large-seeded wild grasses mentioned in this chapter, and the worldwide survey of locally available big mammals to be presented in the next chapter, agree in showing that all those areas of nonexistent or limited indigenous food production were deficient in wild ancestors of domesticable livestock and cereals.

我们发现,新月沃地、新几内亚和美国东部的这些差异,直接来自可以用来驯化的野生动植物的不同系列,而不是来自这些族群本身的局限性。当更多产的作物从别处引进时(新几内亚的甘薯,美国东部的墨西哥三位一体的作物),当地族群迅即利用了它们,加强了粮食生产,从而大大地增加了人口。如果把范围加以扩大,依我看在地球上的一些根本没有在当地发展出粮食生产的地区——加利福尼亚、澳大利亚、阿根廷无树大草原、欧洲西部等等——适合驯化的野动植物可能比新几内亚和美国东部还要少,因为在新几内亚和美国东部至少还出现了有限的粮食生产。事实上,无论是本章中提到的马克·布卢姆勒在世界范围内对当地现有的大籽粒野生禾本科植物的调查,还是下一章中将要述及的在世界范围内对当地现有的大型哺乳动物的调查,都一致表明,所有这些不存在本地粮食生产或只有有限的本地粮食生产的地区,都缺少可驯化的牲畜和谷物的野生祖先。

Recall that the rise of food production involved a competition between food production and hunting-gathering. One might therefore wonder whether all these cases of slow or nonexistent rise of food production might instead have been due to an exceptional local richness of resources to be hunted and gathered, rather than to an exceptional availability of species suitable for domestication. In fact, most areas where indigenous food production arose late or not at all offered exceptionally poor rather than rich resources to hunter-gatherers, because most large mammals of Australia and the Americas (but not of Eurasia and Africa) had become extinct toward the end of the Ice Ages. Food production would have faced even less competition from hunting-gathering in these areas than it did in the Fertile Crescent. Hence these local failures or limitations of food production cannot be attributed to competition from bountiful hunting opportunities.

请回忆一下:粮食生产的出现涉及粮食生产与狩猎采集之间的竞争问题。因此,人们也许想要知道,粮食生产出现缓慢或没有出现粮食生产这种种情况,可能是由于当地可以猎取和采集的资源特别丰富,而不是由于适合驯化的物种特别容易获得。事实上,当地粮食生产出现很晚或根本没有出现粮食生产的大多数地区,向狩猎采集族群所提供的资源特别贫乏而不是特别丰富,因为澳大利亚和美洲(而不是欧亚大陆和非洲)的大多数大型哺乳动物,到冰期快结束时已经灭绝。粮食生产所面临的来自狩猎采集的竞争,在这些地区甚至比在新月沃地少。因此,在当地未能出现粮食生产或粮食生产受到限制这些情况,决不能归咎于来自大量狩猎机会的竞争。

LEST THESE CONCLUSIONS be misinterpreted, we should end this chapter with caveats against exaggerating two points: peoples' readiness to accept better crops and livestock, and the constraints imposed by locally available wild plants and animals. Neither that readiness nor those constraints are absolute.

为了不使这些结论被人误解,我们在结束这一章时应该提出不可夸大两个问题的告诫:一些族群接受更好的作物和牲畜的意愿,和当地现有的野生动植物所带来的限制。这种意愿和限制都不是绝对的。

We've already discussed many examples of local peoples' adopting more-productive crops domesticated elsewhere. Our broad conclusion is that people can recognize useful plants, would therefore have probably recognized better local ones suitable for domestication if any had existed, and aren't barred from doing so by cultural conservatism or taboos. But a big qualifier must be added to this sentence: “in the long run and over large areas.” Anyone knowledgeable about human societies can cite innumerable examples of societies that refused crops, livestock, and other innovations that would have been productive.

我们已经讨论了许多关于当地族群采纳在别处驯化的更多产的作物的例子。我们的一般结论是:人们能够认识有用的植物,因此大概也会认识当地适合驯化的更好的植物,如果这种植物存在的话,而且他们也不会由于文化保守主义和禁忌而不去那样做。但是,必须对这句话加上一个重要的限定语:“从长远观点看和在广大地区内”。任何一个了解人类社会的人都能举出无数的例子,来说明一些社会拒绝接受可能会带来利益的作物、牲畜和其他新事物。

Naturally, I don't subscribe to the obvious fallacy that every society promptly adopts every innovation that would be useful for it. The fact is that, over entire continents and other large areas containing hundreds of competing societies, some societies will be more open to innovation, and some will be more resistant. The ones that do adopt new crops, livestock, or technology may thereby be enabled to nourish themselves better and to outbreed, displace, conquer, or kill off societies resisting innovation. That's an important phenomenon whose manifestations extend far beyond the adoption of new crops, and to which we shall return in Chapter 13.

当然,我并不赞成那种明显的谬论,即认为每一个社会都会迅速地采纳每一个可能对它有益的新事物。事实上,在整个大陆和其他一些包含数以百计的互相竞争的广大地区,有些社会对新事物可能比较开放,有些社会对新事物可能比较抵制。那些接受新作物、新牲畜或新技术的社会因而可能吃得更好,繁殖得更快,从而取代、征服或杀光那些抵制新事物的社会。这是一个重要的现象,它的表现远远超过了采纳新作物的范围,我们将在第十三章再回头讨论这个问题。

Our other caveat concerns the limits that locally available wild species set on the rise of food production. I'm not saying that food production could never, in any amount of time, have arisen in all those areas where it actually had not arisen indigenously by modern times. Europeans today who note that Aboriginal Australians entered the modern world as Stone Age hunter-gatherers often assume that the Aborigines would have gone on that way forever.

我们的另一个告诫涉及当地现有的野生物种使粮食生产的出现所受到的限制。我不是说,在所有那些在现代以前实际上不曾在当地出现粮食生产的地区,不管经过多少时间也不可能出现粮食生产。今天的欧洲人因为看到澳大利亚土著进入现代世界时的身份是石器时代的狩猎采集族群,便常常想当然地认为这些土著将永远如此。

To appreciate the fallacy, consider a visitor from Outer Space who dropped in on Earth in the year 3000 B.C. The spaceling would have observed no food production in the eastern United States, because food production did not begin there until around 2500 B.C. Had the visitor of 3000 B.C. drawn the conclusion that limitations posed by the wild plants and animals of the eastern United States foreclosed food production there forever, events of the subsequent millennium would have proved the visitor wrong. Even a visitor to the Fertile Crescent in 9500 B.C. rather than in 8500 B.C. could have been misled into supposing the Fertile Crescent permanently unsuitable for food production.

为了正确认识这种谬误,请考虑一下有一个天外来客在公元前3000年访问了地球。这个外星人在美国东部可能没有看到粮食生产,因为直到公元前2500年左右粮食生产才在那里开始出现。如果这个公元前3000年的外星人得出结论说,美国东部野生动植物所造成的限制永远排除了那里的粮食生产,那么在随后1000年中发生的事情可能证明这个外星人错了。甚至是在公元前9500年而不是8500年来到新月沃地的游客,也可能会误以为新月沃地永远不适合粮食生产。

That is, my thesis is not that California, Australia, western Europe, and all the other areas without indigenous food production were devoid of domesticable species and would have continued to be occupied just by hunter-gatherers indefinitely if foreign domesticates or peoples had not arrived. Instead, I note that regions differed greatly in their available pool of domesticable species, that they varied correspondingly in the date when local food production arose, and that food production had not yet arisen independently in some fertile regions as of modern times.

换言之,我的论点不是说加利福尼亚、澳大利亚、欧洲西部以及没有本地粮食生产的所有其他地区没有可驯化的物种,而且如果不是外来的驯化动植物或族群的到来,那些地方可能仍然为狩猎采集族群无限期地占有。相反,我注意到地区之间在现有的可驯化物种的储备方面差异甚大,这些地区的本地粮食生产出现的年代也相应地有所不同,而且在某些肥沃地区直到现代仍没有独立出现过粮食生产。

Australia, supposedly the most “backward” continent, illustrates this point well. In southeastern Australia, the well-watered part of the continent most suitable for food production, Aboriginal societies in recent millennia appear to have been evolving on a trajectory that would eventually have led to indigenous food production. They had already built winter villages. They had begun to manage their environment intensively for fish production by building fish traps, nets, and even long canals. Had Europeans not colonized Australia in 1788 and aborted that independent trajectory, Aboriginal Australians might within a few thousand years have become food producers, tending ponds of domesticated fish and growing domesticated Australian yams and small-seeded grasses.

澳大利亚这个据称最“落后的”大陆很好地说明了这个问题。澳大利亚东南部是这个大陆上水源充足、最适合粮食生产的地方。那里的土著社会在最近的几千年里似乎一直在按照一种可能最终导致本地粮食生产的发展轨迹在演化。它们已经建立了过冬的村庄。它们已经开始加强利用它们的环境,建造渔栅、编织渔网,甚至挖掘长长的水渠来从事渔业生产。如果欧洲人没有在1788年向澳大利亚殖民,从而中途破坏了那个独立的发展轨迹,那么澳大利亚土著也许不消几千年就可成为粮食生产者,照料一池池驯化了的鱼,种植驯化了的澳大利亚薯蓣和小籽粒的禾本科植物。